He stood cold in the gathering dawn, peering deep into the chilled, flowing water. A sudden shiver ran through him, partly from the fresh winter wind and partly from the thrill he felt every time he came back to this secluded little stream. He had looked forward to this day for so long; indeed, the anticipation of returning here was the thing that had sustained him for months. He had no way of knowing that he was already halfway through his final year.

But now that I think about it, maybe he did.

Dying was no big deal. He’d already died once, and except for the efforts of some very committed people, he’d have gone on then. Now the memory of that day and the days that followed were like an aged and faded photograph to him, one slightly out of focus with the color mostly gone and the edges only a little less blurred than the center. Somehow it was an image too dim and unimportant for him to care about keeping. Today only the stream and the trout mattered. Dying was no big deal.

Since his heart attack, people who loved him had urged him to take things easier, or at least not to go fishing alone. He knew that it was simply not realistic to expect them all to understand that his best medicine would be the solitude he’d found here on this stream nearly a lifetime ago. But he also knew that if he couldn’t fish and live his life the way he wanted to, he might as well be dead already.

He’d told them so.

The little spring-fed creek flows into the uppermost lake where the big trout spend their summers feeding and fattening and waiting for the seasons to change to the time when they can return to the places where they themselves became trout. Back in the early fifties he’d had a hard time believing the rumors about the big fish that were supposed to live there. But he and his cousin Verlin had finally found the little creek where the big trout return in winter.

Now it was he who returned, seeking his own continuity. Standing by the edge of the stream, he sensed for the first time since the heart attack that this life was once again truly his own and that he was finally free to carry his still-weakened heart down to the edge and into the cold, fuming water. It would be all right.

He walked back to the car and poured himself a cup of coffee from the old Thermos, sipping it slowly as he pulled on his waders. He’d always had a cigarette before as he did this, but now a cigarette was strictly out of the question. He felt grit beneath his toes when he stood, but he did not want to spend the energy it would cost to pull the waders off and clear them. Anyway, it really didn’t matter; the sand was from this stream, and he knew there would be more.

He lifted his old fiberglass fly rod from behind the seat and eased the two sections together, rolling the cold metal ferrule against his oily forehead before slipping it into place. He had tied on a bare, freshly sharpened hook the night before and attached two tiny split-shot to the drop-line. Now he removed one of them; the water was running a little low this morning.

He unscrewed the lid from one of his granddaughters’ old baby food jars and lifted out an egg sack he had tied last winter. He carefully eased it past the barb and stuck the point of the hook into the scarred cork handle of the fly rod. Then, sliding the jar back into his vest pocket, he closed the car door without locking it and eased down the trail to the stream.

His first few steps into the water were nearly a Baptism. It was good to sense the ancient gravel beneath his feet and once again feel the familiar details of the streambed telegraphed up the rod into his bare, warming hands as the split-shot rode the water-worn gravel where newly deposited trout lay awaiting their births. The winter wind was clear and sweet and it gently stung the tender lining of his clearing lungs as he recalled all the trout and all the men he had come to know on this creek, absent this morning of all human life but his own.

He worked the water smoothly and methodically, with an expertise and economy of effort that comes only with a lifetime of trout fishing. He had been casting for twenty minutes when his bare fingers began to chill, and he thought about moving on. But he made one more cast slightly upstream into the edge of the current and felt the line sweep along the bottom past him. Then as he lifted his rod at the end of the drift, he recognized an old familiar pressure.

He accelerated his lift and felt the full power of the trout as it erupted into the air, its silver sides streaked with crimson as it hung there broadside in a singular shaft of morning amber. Then, just as suddenly, the hook pulled free from its gaping jaw and the trout twisted back into the water and was gone. It had won its battle, but so, too, had he. Already it had been a good day.

By 11:30 he had worked his way up past the bridge, nearly all the way to the little white church that sits on a small hill overlooking the stream, and he found himself quietly singing along with some of the more familiar hymns as they drifted across the meadow toward him. Finally, he returned to the car and drove down to the Falls; but he knew it would be unwise to descend the trail here, for he would eventually have to climb back out.

Still, as he surveyed this magnificent stretch of water so far below, he unconsciously dissected each run with his still-keen memory and could almost feel the streambed as his steel-blue eyes danced across the moving surface of the water, and he thought about some of the trout he’d taken here.

There below Cook Hollow was the six-and-a-half pounder that had led him on such a wild run before Verlin had finally been able to net it. And there below the Falls was the twenty-four inch rainbow his young son had fished over for nearly thirty minutes. The boy had eventually grown impatient and moved, only to see his Dad hook the trout on his third drift. It had taken nearly fifteen minutes to land the fish, and a crowd of other fishermen had gathered to watch as he finally brought it to net.

He remembered how proud his boy had been as together they’d carried the great fish up the steep slope to the car. Back then, they often kept the trout they caught, for these were men who frequently fed their families from the providence of their streams. Many times he and his boy had lain face down together on the hanging rock at the head of the falls and watched as the fish leapt their way upstream to find the ancient gravel beds where they themselves had become trout.

But on this cold, perfect morning, he had no way of seeing his son down there alone in the warm pre-dawn light six months from now, fishing a few small stones from the stream to bring back and place beside him in his casket.

Suddenly he realized he was hungry—not simply ready for some lunch, but really hungry. It was good to be hungry again. He walked back to the car and unwrapped one of the sandwiches his wife had made for him the night before. The flavors of the cold meats had mingled delicately with the homemade bread and the rich brown mustard, and the hot coffee felt soothing as it followed the sandwich down.

He felt so good. This was the best day he’d had in months. It was nice to feel good again; he’d had such a good morning; perhaps now was a good time to leave.

But no! He was enjoying himself too much to leave. He knew where he could fish, a mile upstream at a place where he wouldn’t have to climb so far down to the creek. In ten minutes he was there.

He parked next to the old stone barn and cinched up his hip-waders. Then with his fly rod in hand, he crossed the barbed wire fence where the top strand went missing twenty years ago and started walking toward the sound of living water.

I wish I knew how it happened.

I wish I knew every delicious detail of how he caught that trout. He called me that night to tell me about it, but I was too excited to get all the details, and he was too excited to tell. Now I don’t remember whether he caught it on an egg sack or on one of the little yarn patterns he’d learned to tie in Michigan. I don’t know whether he hooked it above the riffle that splits the run or below it.

I don’t even know what color shirt he wore.

But I do know he kept that trout above him. He would always try to apply downstream pressure to a big fish as soon as he hooked it and then rely on its instinct to resist the pull and head upstream. It’s much easier to play a big fish if you can stay below it where it can’t use the force of the current against you. He taught me this when I was a little boy.

I know he played that trout as carefully as any fish he ever caught, for though he had his old net strung across his right shoulder, he didn’t use it. I know the fish weighed about three-and-a-half pounds, because he said so. I know it was a female, swollen with still-forming trout.

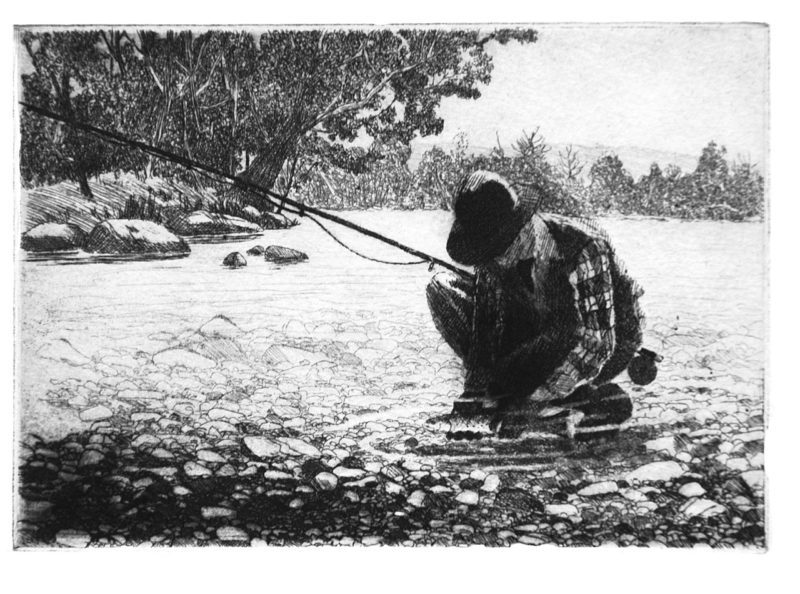

And I know that when he finally worked her in close to the edge, Dad knelt there in the icy current, carefully slipped the hook from the corner of her mouth, and watched his last Rainbow slowly swim away.

This is the Title Chapter from the book, THE LAST BEST DAY. Signed copies of this and other books the author has written or to which he has contributed can be secured from Sporting Classics at SportingClassicsStore.com—click on “BOOKS.”

Or simply call 1-800-849-1004.

The author welcomes and greatly appreciates your comments, questions, critiques, and input. Please keep in touch at Mike@AltizerJournal.com.

The painting and still life are by the author. The etching “given back” is by Brett James Smith.