“Ahead of his time” falls short. His tenacity matched his genius.

But war and the Depression would have their way.

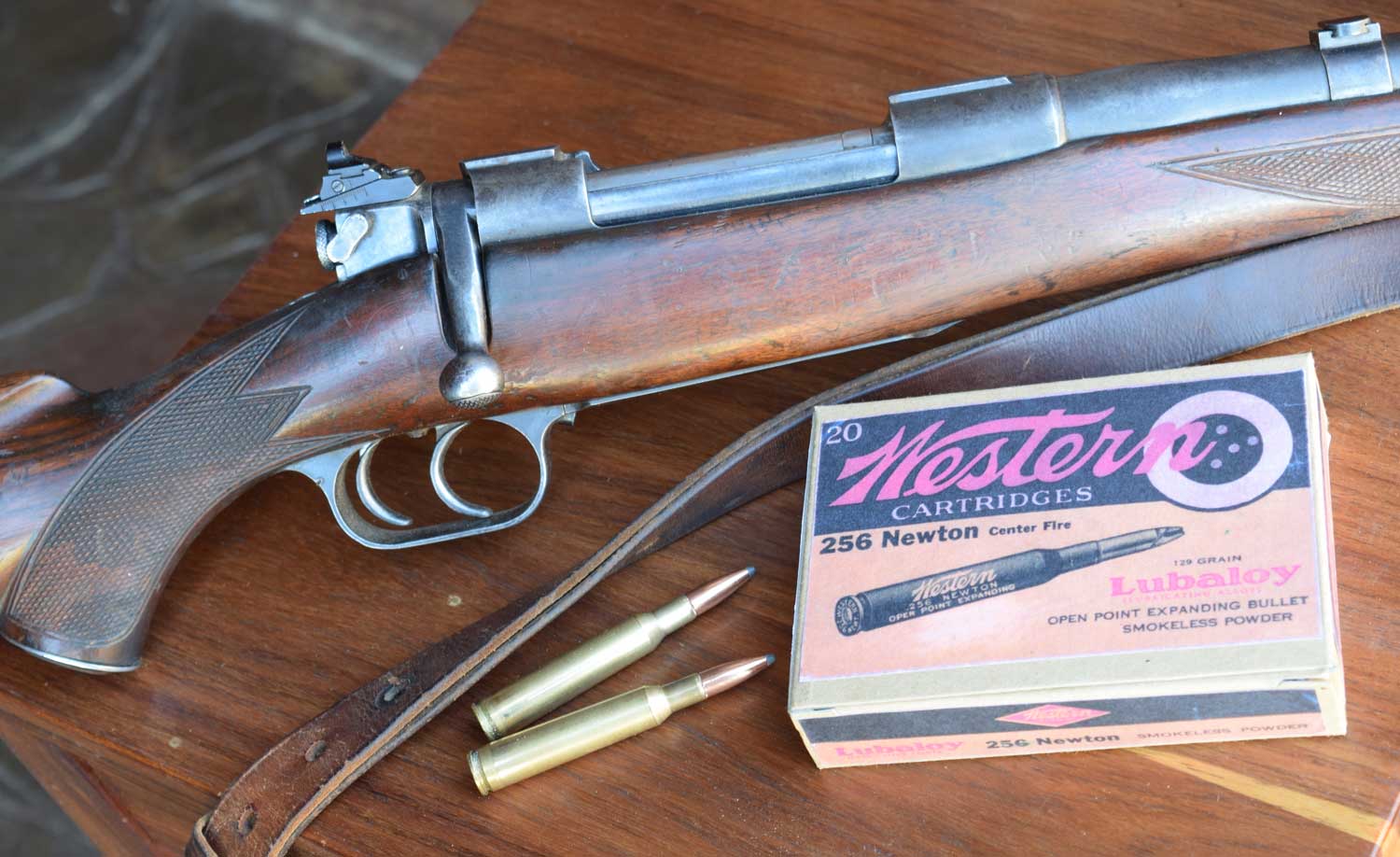

When rifle maker Buzz Fletcher asked me to photograph a Mauser he’d stocked, I said, “Sure!” Would I like some 256 Newton brass to check it on the range? Sure!

Long and lean, with dark tiger-tail wood, the rifle was beautifully sculpted and checkered. The satin blue met walnut’s glow in skin-snug seams. The bolt ran as if on greased bearings. Light and lively in hand, with the balance of a dancer, the rifle came on target instantly.

The Williams sight added to this Newton proved practical—a better option than drilling that receiver!

The 256 Newton was developed before WW I. Western Cartridge loaded it until 1938 with 129-grain bullets at a claimed 2,760 fps. Essentially a 6.5-06, its case is just 0.1 inch shorter than a 270 Winchester. My handloads would drive 129-grain Hornadys at more than 2,900 fps, 140s at more than 2,800.

That was my only contact with a Newton cartridge for years. Then, on a women’s safari I hosted in Namibia, a young lady showed up with her father’s Newton rifle. Her brothers had loaded ammunition, even found some old box labels for my photographs. A practiced hunter and shooter, Tamar handily killed plains game with her 256 Newton. Then she handed it to me.

My mission: a wildebeest cow for the larder. A south wind on one side, red sunset on the other, I angled toward a herd moving briskly through low bush. Cover got thick before I got close enough for a shot with the aperture sight. Then a snort told me this frolic was over. Belly to sand, I elbowed under the thorn, gaining yards. Through the lattice, I saw a cow join the bull, both now staring. I crabbed to the side, found a slot. The bead quivered just inside the shoulder. An audible strike followed the blast. I let the dust settle in the herd’s wake. The trail was bright from the Hornady’s exit. She lay 40 steps on.

Charles Newton was born January 8, 1870, in Delavan, New York. He worked on the family farm until, at age 16, he finished school. After a two-year stint teaching, he turned his quick mind to the study of law. Admitted to the state bar, he found courtrooms uninspiring. But six years in New York’s National Guard drew him to cartridge design with then-new smokeless propellants. Later, with German immigrant Fred Adolph, he began designing firearms.

When WW I nixed delivery of Mauser actions for Newton rifles, the inventor went on to design his own.

Adolph, a talented gunsmith when he came to the U.S. in 1908, set up shop in Genoa, New York. By 1914, he’d published a catalog of rifles, shotguns and combination guns. Some were imported; he built the others. He became known for chambering high-velocity hunting cartridges, commercial and wildcat. Besides his own, he offered nearly a dozen by Charles Newton. The smallest, but perhaps best known, was the 22 Hi-Power or “Imp.” A 1905 development on the 25-35 case, it sent 70-grain .228-inch bullets at 2,800 fps from a charge of 25 grains Lightning powder. Savage adopted it late in 1911. In Model 1899 rifles, the Hi-Power earned larger-than-life credentials on beasts as formidable as tigers! Closer to home, it proved deadly on deer. It also drew attention to range limits imposed by blunt bullets and metallic sights. Newton noted that from a 6-pound Savage rifle, accuracy was “good for about a 4-inch circle at 200 yards.”

Newton’s ideas first served the rifles of his day. Lever-action Winchesters—1886, 1892 and 1894—with side-ejecting Marlins firing the same cartridges, were hugely popular. Savage offered an appealing alternative: the hammerless 1899. Its ingenious spool magazine was protected by the forged receiver and kept rifle balance constant as it emptied. And as hunters pointed out, it didn’t “catch the wind” like under-barrel tubes. While Savage’s 303 cartridge was loaded with customary round-nose bullets, the spool also permitted use of pointed bullets, an option denied tube-fed rifles, with primers forced by spring pressure and recoil onto bullet noses. When fast bullets of modest diameter replaced missiles inherited from blackpowder designs and scopes supplanted open sights, pointed bullets would rule in deer camps.

That trend was already showing up as surplus Mauser, Krag and Springfield rifles made their way afield. Prescient wildcatters such as Newton were convinced the future belonged to bolt rifles. He focused on case designs to serve them. In 1912 he necked the 30-06 to .257-inch, calling it the 25 Newton Special. About that time, he also delivered to Savage a short, rimless .250-caliber cartridge that followed the 22 Hi-Power as a new chambering for the 1899 lever rifle. While Newton suggested a 100-grain load, Savage chose an 87-grain bullet at 3,000 fps—lightning speed when top-selling loads for whitetails clocked around 2,000. The resulting 250/3000 moniker drew attention to that velocity.

Wildcatters pounced on the 30-40 Krag, in 1892 the U.S. Army’s first smokeless small-bore cartridge.

Newton’s frisky .250 would inspire work by other wildcatters. J.B. Smith, John Sweaney, Harvey Donaldson, J.E. Gebby and Grosvenor Wotkyns all necked it to .22 caliber. A 1937 version by Gebby and Smith became the 22-250 “Varminter,” one of the fastest and best-selling small-bore centerfire cartridges ever. Its long career as a wildcat ended when Remington picked it up in 1965. It is now factory-loaded by every major ammunition company.

On the eve of the Great War, Newton’s 7mm Special foreshadowed the 280 Remington by more than 40 years (as did the 7×64 developed by the brilliant Wilhelm Brenneke in Germany). After armistice, Newton helped bring the 300 Savage to its 1920 debut. Designed for Savage’s improved Model 99 rifle, its compact 1.87-inch case held 10 percent more power than a 30-30.

Working to wring high velocities from short hulls, Newton also pondered ways to reduce velocity loss downrange—thinking that would eventually spark the current trend to short, sharp-shouldered small-bore cartridges firing long, pointed bullets through fast-twist rifling at steel targets far away. His 22 Long Range pistol cartridge featured a shortened, necked-down 28-30 Stevens case. Its jacketed .228-inch spitzer bullet was the same as used in the 22 Hi-Power. The 22 Newton on necked-down 7×57 brass drove 90-grain bullets at 3,100 fps from fast-twist 1:8-inch rifling. That cartridge held 14 percent more powder than the 220 Swift, also credited by some to Newton. Reportedly, his 22 Special on the 30-40 Krag case sent 68-grain bullets at nearly 3,300 fps.

A century ago, wildcat cartridges were fashioned for Winchester’s 1885 single-shot. Here, a 25 Krag.

For hunters after big, durable beasts, Newton modified or developed rimless cases bigger than the 30-06’s. His 30 Newton was originally the 30 Adolph, fashioned on the 11.2×72 (.440-caliber) Schuler case. But Adolph used rebated, Berdan-primed brass; apparently Newton had Union Metallic Cartridge produce cases for Boxer primers, popular stateside. UMC brass was also stronger than Adolph’s European cases, whose heads were turned down to fit standard Mauser bolts. Of the 30 Adolph, Colonel Townsend Whelen opined: “The velocity and energy, particularly of the 172-grain load, are so well retained at long ranges that it is doubtful if any other rifle now made can [perform better] at ranges over 300 yards….”

The 30 Newton’s 2.52-inch case with .525-inch head had the profile of later belted .30-caliber magnums. But beyond the constraints imposed by the Depression, demand for such a big, powerful cartridge was tepid. Hunters of that day had grown up on 30-30s. To them, the 30-06 landed a mighty blow indeed—enough smash for the toughest North American game. There was little call for expensive rifles that kicked harder than a Springfield and used hard-to-find ammunition. Western Cartridge loaded 30 Newton ammunition shortly after its debut until about 1938. On the heels of WW II, Richard Speer sold cases. A later source was Jamison Cartridge. The 375 Ruger, which appeared in 2006, has body dimensions so close to the 30 Newton’s that handloaders have necked it down to form cases.

The 33 and 35 Newton also resulted from Fred Adolph’s re-shaping of the 11.2×72 hull. As with his .30-caliber, Newton replaced turned, Berdan-primed brass with fresh Boxer-primed cases. But these medium-bores were even frothier than the .30-caliber. Recoil from hunting-weight rifles was fearsome. Indeed, the 35 Newton hit harder—on both ends—than factory loads for the 375 H&H! Before WW I, Winchester listed 270-grain bullets from its 375 H&H ammunition at 2,720 fps, for 4,438 ft.-lbs. of energy. But Newton claimed a 250-grain bullet from his 35 Newton could reach 2,975 fps, to land 4,925 ft.-lbs., a decidedly stiffer blow. Developing his 33 and 35, Newton also considered, and in tests may have employed, 404 Jeffery brass.

Both Adolph and Newton gave single-shot rifles their due. Winchester’s Model 1885 welcomed rimmed cases and set no limits on cartridge length. Newton necked the 405 Winchester to 7mm, even to .25 caliber. He developed 30, 8mm and 35 Express rounds from 3 1/4-inch Sharps hulls.

One of Newton’s most celebrated efforts was the 256 Newton, a versatile cartridge suited to deer and a range of other animals commonly hunted. Oddly enough, it was not named for its bullet or groove diameter, but for the bore. Like modern 6.5mm cartridges, it fired a .264-inch bullet. Newton preferred it to the wildcat 25-06 (.257-inch bullet) because in that day dimensions of 25-06 chambers were not standardized, so neither were pressures. Also, Mauser produced 6.5mm barrels, part of Newton’s plan for his next project.

Early on, Newton had dreamed of building his own rifles. In 1914 he formed the Newton Arms Company in Buffalo, New York. With a factory under construction, he traveled to Germany to secure a supply of rifle actions from Mauser and J.P. Sauer & Sohn. He intended to re-barrel them to 256 Newton and 30 Adolph Express, then add stocks. A flier advertised 256 Newton barrels “of the best Krupp steel” with raised, matted ribs and sight slots. Price: $17! In March 1915, the first rifles appeared in a Newton catalog. Their ’98 Mauser actions wore barrels in 256, 30 and 35 Newton. Fred Adolph and California gunsmith Ludwig Wundhammer provided sporting-style stocks. Available in three grades, the rifles were priced from $42.50 to $80.

The pre-WWI 256 Newton, essentially a slightly shortened 6.5/06,

used .264-inch diameter (6.5mm) bullets.

Newton’s timing could hardly have been worse! The first two dozen Mauser rifles were slated to arrive August 15, 1914. The assassination of the Archduke Ferdinand triggered action from treaty-bound signators across Europe. Germany went to war August 1. All hopes for quick resumption of trade between the U.S. and Germany were dashed. So Charles Newton tapped the Marlin Firearms Company for barrels in 256 Newton, threaded for 1903 Springfield actions. His intent: sell them for $12.50 as replacements for 30-06 barrels to hunters convinced the 256 Newton offered a ballistic advantage, as Newton claimed. Fitting barreled actions to Springfield sporter stocks would be easy. But rifle actions and components, including barrels, were in short supply. All arms factories were madly fulfilling lucrative government contracts.

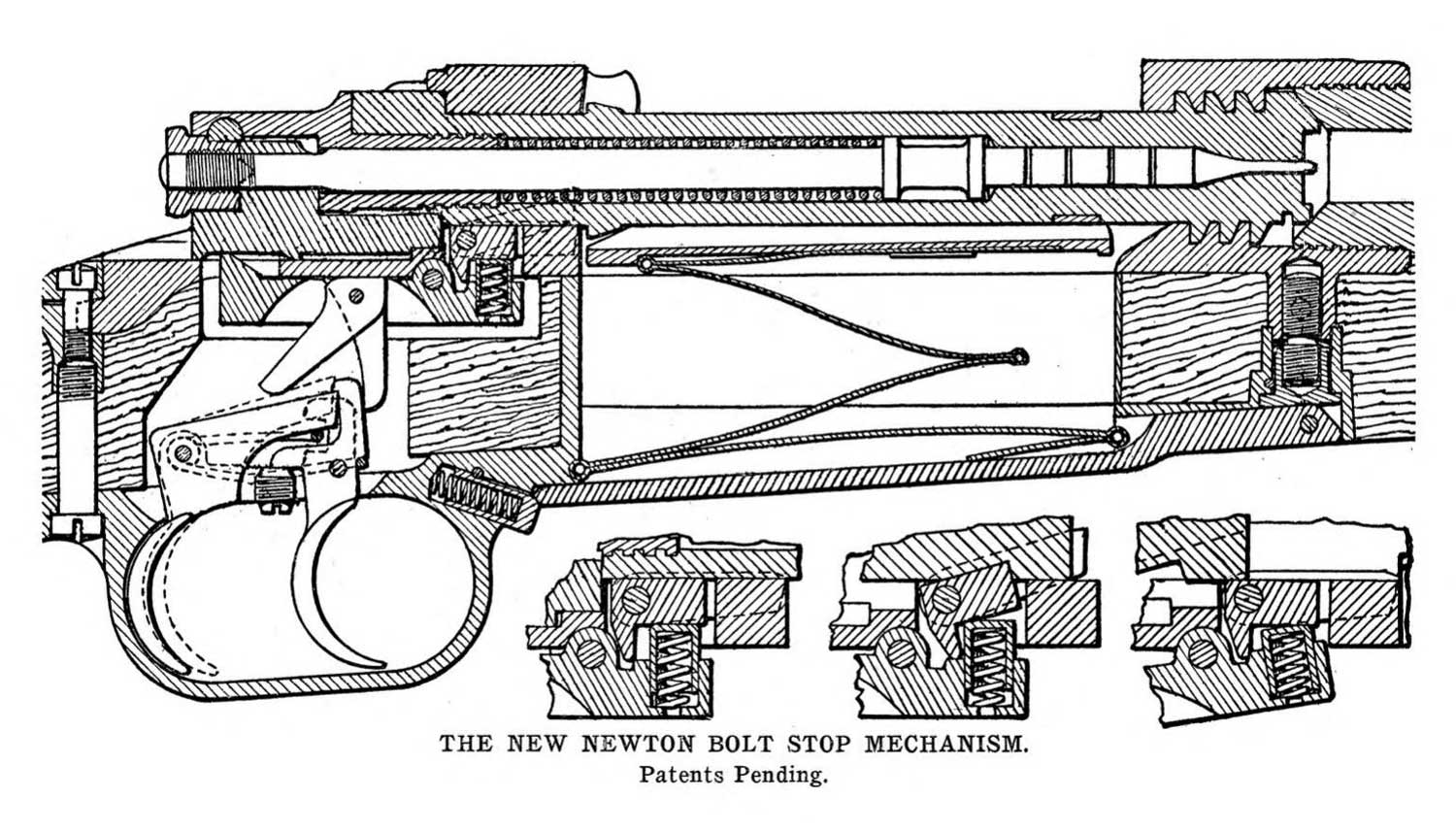

Newton quickly took another tack. By 1916 he had incorporated the best features of Mauser and Springfield actions in a rifle whose only non-original part was the mainspring. He hired legendary barrel-maker Harry Pope to oversee production of Newton barrels. (He would later credit Pope for helping him develop segmented rifling for those barrels.)

Newton rifles had elegant profiles. Note here Mauser influences, but a new safety, cocking piece sight.

The first Newton rifles went on sale January 1, 1917. They got favorable reviews. But once again the timing was poor. Just three months later, the U.S. entered WW I, the government assuming control of all domestic ammunition production. Though Newton loaded his own, he relied on Remington for cases. Early in 1918, Newton cartridges were coming off the belts. But the company’s balance sheets drew no plaudits from banks supporting it. Receivership followed; by year’s end the Newton Arms Company was no more. About 2,400 rifles had been built. Another 1,600 were completed by Bert Holmes, who acquired all assets. Holmes peddled more than 1,000 rifles for $5 each as he tried to bring the Newton factory back into production himself.

Charles Newton wasn’t beaten; nor did he sit quietly by in April 1919, as New York machinery dealers Lamberg, Schwartz and Land formed the Newton Arms Corporation. Their plan was to market as genuine Newton rifles several bin-loads of poorly finished arms they’d bought from Bert Holmes. Charles Newton got a delayed settlement. Marshaling his assets on April 19, he launched the Chas. Newton Rifle Corporation, his plan to equip a new factory with surplus tooling from Eddystone Arsenal.

The Eddystone deal faltered. The only rifles shipped by the Chas. Newton Rifle Corporation were commercial Mausers. They had butterknife bolt handles, triple leaf sights and double set triggers. Some featured parabolic rifling, some a “cloverleaf muzzle”—grooves ostensibly to vent gas uniformly to keep residual pressure from tipping bullets. Newton stocked the rifles, drew roughly 1,000 orders, but Mauser actions were delayed by Germany’s overheated postwar economy.

Only 100 or so arrived in New York.

Doggedly optimistic, Charles Newton scrambled to start another venture in 1923. Arthur Dayton and Dayton Evans, who’d helped him bankroll his 1919 company, backed him. The Buffalo Newton Rifle Corporation, founded in Buffalo, soon moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where its first rifles shipped in 1924. Their interrupted-thread bolt lock-up would appear in Weatherby and other rifles much later. The four-groove nickel-steel barrels were chambered to 30-06 and four Newton cartridges: 256, 280, 30 and 35.

A crossbolt behind the magazine reinforced the walnut stocks; but there was no receiver lug to arrest recoil, and many stocks split. Western Cartridge Company produced Buffalo Newton ammunition.

Operating money had become scarce for Charles Newton. After tapping out his life insurance, he pleaded with Marlin’s Frank Kenna to build Newton rifles under contract. The astute, conservative Kenna demurred. Insisting his company was poised to turn around, Newton pointed out that Marlin could build rifles for $8 each and, at a production rate of 1,000 rifles a month, could profit nicely. At that time Buffalo Newton rifles retailed for $60. Kenna held firm.

Charles Newton’s rifle featured multiple-lug, interrupted-thread lock-up. Note the Mauser-style extractor.

In 1929, after producing about 1,500 rifles, the Buffalo Newton Rifle Corporation folded. Charles Newton, immediately applied his engineering talents to another action. Unveiled in the New Newton Straight Pull Rifle, its two-lug bolt and ’03 Springfield cocking piece suggested bolt-action ancestry. But there were also elements of Winchester lever-action and Lee Navy straight-pull designs. Newton dubbed the rifle the “Leverbolt.” If Marlin produced the rifle, he told Frank Kenna he would split profits down the middle. To meet Kenna’s proof of demand, Newton published a flyer soliciting a $25 down-payment for each $70 Leverbolt, the remainder due on receipt of the rifle.

His offer did not secure the 500 orders Marlin required to participate.

The stock market collapse in October dashed the dreams of many Americans, Newton included. His rifle company yet unrealized and his energies spent, he died, age 62, in New Haven, March 9, 1932.

The 256 Newton of 1913 performs much like the hugely popular 6.5 Creedmoor, introduced in 2009.

Charles Newton’s pioneering efforts in cartridge design came clear as belted magnums wrested market share from the 30-06. In 1913 his 30 Newton out-performed the 300 H&H Magnum that arrived a decade later—and pre-dated the spate of spunky .300s developed to package magnum muscle for 30-06-length actions. The 30 Newton was the 308 Norma and 300 Winchester Magnum without a belt, half a century early! A generation before Roy Weatherby, Newton was sending big game bullets faster than Mach 3—and giving hunters one of the best deer cartridges ever. His 256 Newton has much in common with Europe’s 6.5×54 Mannlicher-Schoenauer, a favorite of storied hunters of its day, including F.C. Selous, Charles Sheldon and W.D.M. Bell. Its pencil-length bullets downed Alaska’s biggest game and, fully jacketed, penetrated elephant skulls. Meantime, it toured sheep country in svelte Mannlicher-Schoenauer carbines. I’ve used the 256 Newton afield only a little but found it delightful, a match for the wildly popular 6.5 Creedmoor, unveiled in 2009. My handloads for the 256 trump many factory loads for the Creedmoor, and some for the 270 Winchester!

Charles Newton tried various bullet designs, too. In 1914 he wrote of imbedding a copper wire “in the center of the bullet point [to protect] the point against every deformation except upsetting.” This bullet also had paper insulation between jacket and core so barrel friction wouldn’t melt the core. He had found evidence of lead melt by drilling holes in jackets, then firing into cardboard and observing lead smears at bullet entries. His 1915 idea for a partitioned core to resist bullet disintegration during high-speed impact would occur to John Nosler in 1947.

Some features of modern rifles came first to Newton’s—not just multiple-lug, interrupted-thread locking and straight-pull bolts, but the three-position safety installed after WW II on Winchester Model 70s and now a selling point on other bolt-actions. Oddly enough, the elegant, nimble profile of Newton’s rifles, at once classic and modern, now bucks a trend to beefier stocks with adjustable combs, steep grips and bulbous forends. Magazines and bipods protrude. Pic rails and muzzle devices have supplanted open sights and the lovely cocking-piece aperture installed on some Newtons.

Charles Newton earned more than he got for his brilliant work. His story is less one of invention and production than of an enduring drive to press on, whatever the obstacles. ν