This section of Claud E. Fuller’s 1954 speech was delivered to the American Society of Arms Collectors. My friend Eric Taylor sent it to me, and it conjured up the time a few decades ago when I over-nighted in the cowboy town of Cody, Wyoming. My plan was to fish for monster trout on the Grey Reef, but I never made it. I got side-tracked at the Cody Firearms Museum.

Colt-Paterson Model 1839 revolving shotgun. Gift of Olin Corporation, Winchester Arms Collection

Inside, I saw a most comprehensive collection of American firearms. Walls were grouped by manufacturer with representations from America’s greats: Winchester, Colt, Remington, Fox, Parker, Marlin and L.C. Smith among many others. There were plain Jane field grades, ornate high-grade sporting rifles, Volcanics, early lever-actions, and pistols, rifles and shotguns galore. There were guns used by Hollywood actors in Western films I’ve seen so often I can quote from them at will.

Each room, each wall, was displayed with museum-quality lighting and a sense of purpose. My own eclectic assortment of rifles, pistols and shotguns, crammed into a black walnut cabinet back home, paled by comparison. Beyond the impressive size of Cody’s 7,000-plus display, my collection was meager and utilitarian. Those words should never be used in the context of a gun collection. I vowed to do something about it.

Scottish-made shotguns represent an emerging trend among collectors. Here, Lars Jacob holds an imported 16-bore Daniel Fraser boxlock.

My inspiration came from the baseline established by the famous chef, the late Julia Child. Child went heavy on ingredients that made good food taste great. “More is better,” she reasoned, and she went heavy on butter, sugar, lard and wine. I applied her view to upgrade and expand my own cabinet.

There are a variety of ways to start a firearms collection. Lars Jacob of Lars Jacob Wingshooting in Dorset, Vermont, described what I saw in Cody.

“Collections usually have a sense of purpose,” he said. “I work with three types of collectors in my gunshop: those who will hunt and shoot their firearms, those who favor unique firearms in pristine condition for display and those who collect memories.

“The first two types are easy to understand, but the third group is interesting,” he noted. “They are ones who deviate from their normal path to try something new.

“Let’s say they favor A.H. Fox shotguns, but have always wanted to shoot an L.C. Smith. They’ll buy a Smith or two, shoot them for a while, and then sell them when they’ve stored enough memories. They resume collecting when something else captures their attention,” Jacob noted.

Lars Jacob ejects the empties from a 1920s-era London Best gun. Many collectible firearms are used for hunting and shooting.

“Over the years, I’ve noticed trends as well. One constant trend is the collectability of American classics. A century ago, American classics were distributed mainly through hardware stores so there are still many low-to-mid grades available. A select number were made in higher grades for customers of distinctive retailers such as the original Abercrombie & Fitch or Clapp & Treat. Others were produced as custom orders. That abundance affords hunters and collectors the opportunity to acquire quality firearms at reasonable prices.

“Trends emerge over time. Three decades ago, there was a high demand for bespoke English guns. Twenty years ago, there was a high demand for bespoke Continental firearms with vigorous sales coming from Italian-made shotguns. A decade and a half ago, small-bore American classics were popular.

“The current trend is toward Scottish guns. The Scots understood the boutique nature of the business and created shotguns with individuality. Joseph Harkom made fewer than 3,000 shotguns in his entire life. Charles Ingram’s classic engravings complete with Celtic accents and deep grapevines are gorgeous.

“Dixon’s round-action trigger plate is one of the most dependable designs ever,” Jacob added. “Unlike bulky boxlocks, Dixon’s unique trigger mechanism is built over-and-behind the trigger, which results in a small, tasteful design. There is a similarity with British gun manufacturers, but when I look at a rack in my gun room, it’s easy to see the Scots’ uniqueness. Trends form in gun collecting as they do with other industries, and right now Scottish guns are hot.”

One common collecting method is to identify a favorite manufacturer and expand from there. It’s evidenced in a collection of Winchester Model 21s, specifically in 28 gauge. Another type of collection focuses on shooting disciplines such as skeet or single-barrel trap guns. This style of collecting is again more common to American classics, mostly because they were not bespoke.

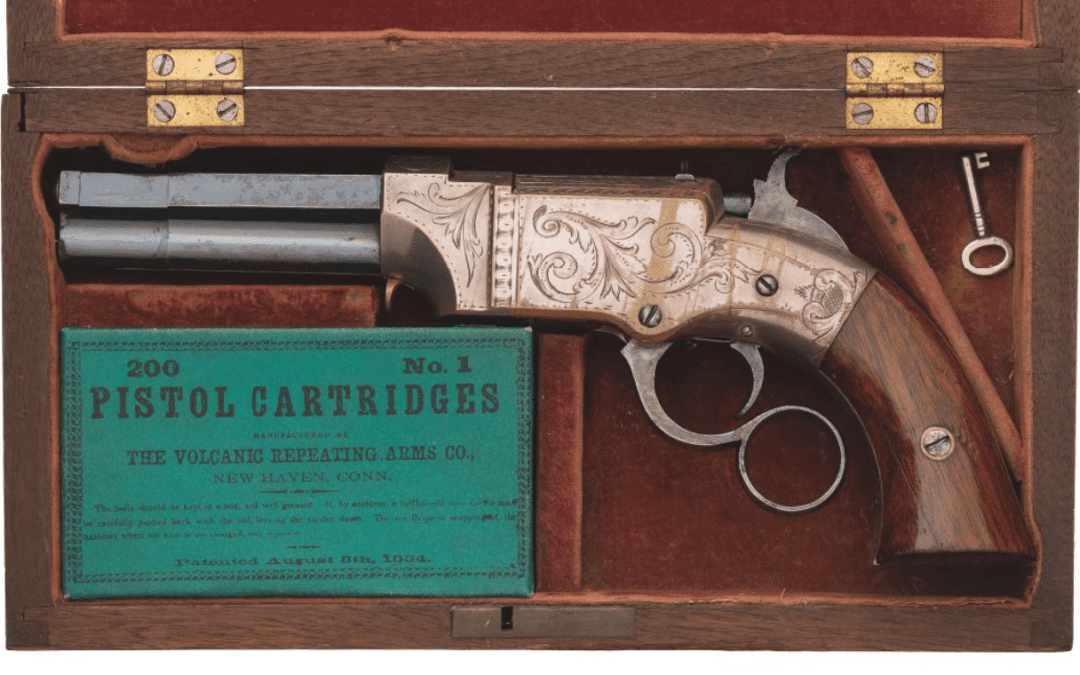

Scarce Factory Engraved New Haven Arms Company Volcanic Lever Action Carbine. Rock Island Auction photo

Numbers don’t lie, but they might give a collector pause. At a Christie’s auction, the gavel dropped at $1,986,000 for George Washington’s flintlock saddle pistols. A gold-inlaid Colt Model 1849 brought $1.1 million, not just because of its 24-carats. It commanded so much money because the pistol showed the evolution of design from the original 1836 Colt Paterson to the smaller, more compact 1849 Pocket Revolver. Texas Ranger Sam Wilson’s Colt Walker, one of 1,100, brought $920,000 at auction, while the 44 caliber Smith & Wesson that killed Jesse James commanded $350,000.

Remember Bo Whoop, the 12-gauge Super Fox owned by Nash Buckingham that’s enshrouded by intrigue? It netted $201,250. Collectors willing to pay those premiums are looking for something in particular. But what?

Provenance.

Adolph Hitler’s gold-inlaid Walther PP was brought to the United States by a soldier who found the handgun in the Führer’s Munich apartment.

Items of provenance need to have some proof of authenticity, which might come from engravings, letters from manufacturers or sales agents, photographs, or other items that prove their value. These types of guns are part of our living history and often command high values.

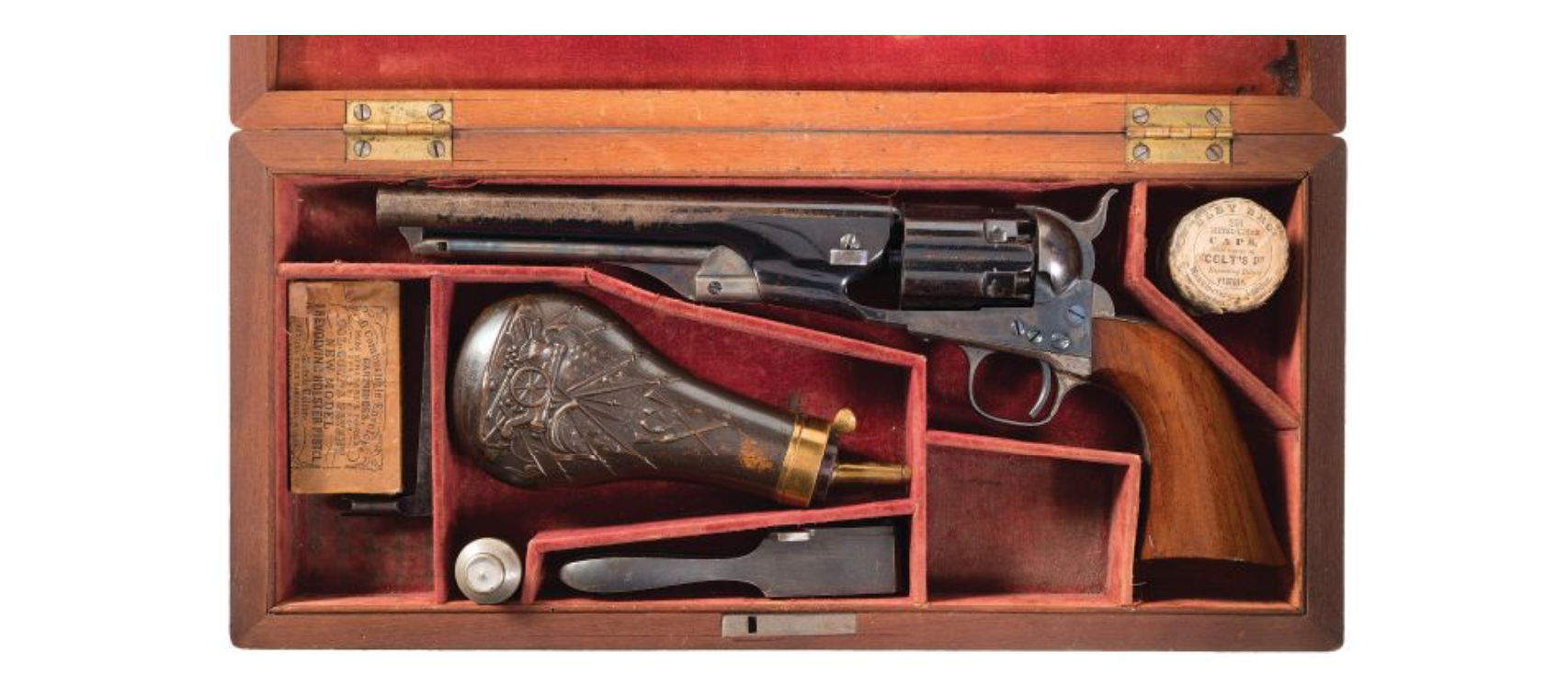

Other items that are regarded as rare typically fetch top dollar. Rock Island Auction Houses’ Colt Model 1860 Army revolver with a unique fluted cylinder showed a design change that separates it from the standard models. Only 4,000 were built, which makes the gun even more valuable. Commemorative models are collectible such as the Winchester 1876 One of One Thousand. That scarcity drives prices up, particularly because only 54 of these models were produced. The Winchester 1873 One of One Hundred is hailed as a Holy Grail among collectors.

Factory Cased Colt Fluted Cylinder Model 1860 Army Percussion Revolver. Rock Island Auction photo

Other auction houses specializing in firearms, such as Amoskeag Auction Company and Morphy Auctions, which has acquired James D. Julia & Sons, broker some of the most unique firearms through their live and web auctions. Some lots feature low serial numbers while others contain collections of related firearms.

Winchester fans are likely to collect Henry rifles and Volcanics because they have a connected history. Prototypes sometimes show up as do unique or industry-changing firearms. Pardon the pun, but regardless of what make or model pulls your trigger, keep Lars Jacob’s comments in the forefront.

A collection should have a clearly defined purpose. Then you can scour the countryside in search of the perfect new acquisition. Just don’t be disappointed if Claud E. Fuller beat you to the punch.

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop now

Following years of research from Sun Valley to Key West and from Nairobi, Kenya to Hemingway’s home in Cuba, this volume significantly expands what we know about Hemingway’s shotguns, rifles, and pistols—the tools of the trade that proved themselves in his hunting, target shooting, and in his writing. Weapons are some of our most culturally and emotionally potent artifacts. The choice of gun can be as personal as the car one drives or the person one marries; another expression of status, education, experience, skill, and personal style. Including short excerpts from Hemingway’s works, these stories of his guns and rifles tell us much about him as a lifelong expert hunter and shooter and as a man. Shop now