We both hunched forward in the classic posture endemic to hunters worldwide when stalking dangerous game. And this was truly a dangerous beast.

It was a Mahler-Besse Château Biré French Bordeaux Supérieur, vintage 1995, and I had been saving that bottle of wine for more than two decades. So when my birthday fell on a Saturday that year, I decided it was time for this lovely and mysterious liquid to breathe some fresh air. I made reservations at a fine little Italian restaurant on the outskirts of Jonesboro, slipped the Mahler-Besse into a handwoven wine basket, called up our friends Jim and Linda Carmichel to see if they could join us and promised to pick them up at 5:30. My wife and daughter and I arrived at their house at 5:15.

True to form, Linda had been ready since 4:30, and Jim was still getting into his tux. By the time he made his grand entrance, I was relaxing in his trophy room salon with as lovely a bevy of beauties as a man should ever be allowed, as Jim passed through on his way to the kitchen to mix a martini. But a few seconds later he suddenly reappeared, and everything changed.

Everyone knows Jim Carmichel. As shooting editor of Outdoor Life for nearly four decades, his work defined what is inarguably the Golden Age of international big game hunting. The Jim Carmichel who had just disappeared into the kitchen was a more elegant edition of his former self, dressed to the nines and ready for a relaxed dinner. But the Jim Carmichel who reappeared a few seconds later was something else entirely.

He didn’t speak. His beckoning wave and urgent expression said everything that needed saying: There was evidently a lion or red stag or herd of Cape buffalo somewhere out by the edge of the forest behind his manor. I jumped off the sofa and headed his way without asking questions.

Now in full “guide” mode, Jim lightly laid his hand on my shoulder and eased me forward, ushering me through the high-ceiling kitchen and past his well-chilled but still empty martini glass, onward to where he always keeps a tricked-out pellet rifle leaning in the corner by the French doors that lead onto the broad veranda.

“Squirrel!” he whispered.

“Where?” I whispered back, before spying the subtle swish of a bushy grey tail as our quarry appeared in the edge of the trees, intent on larceny and already looking guilty.

By now, Jim and I were both hunched forward in the classic posture endemic to hunters worldwide when stalking dangerous game. And this was truly a dangerous beast. For the entire summer and autumn, the pesky critter had been stalking Miss Linda’s multi-story bird feeder, harassing perfectly innocent cardinals and doves and chickadees, and threatening them with furred mayhem if they dared challenge his eminence.

Jim had taken a couple of low-odds shots at him over the past few weeks, but the brazen little bandit had jumped or twitched at the last instant and escaped untouched, chattering his rodentian derision as he disappeared. Determined not to be responsible for the pint-size pillager escaping yet again, Jim reached down, picked up his pellet rifle and thrust it into my hands.

“There’s your bullets,” he whispered as he nodded toward a small saucer containing a half-dozen high-tech lead projectiles resting on the bench next to the door. Checking the safety, I broke open the gun, stuffed a single pellet into the breech, closed the barrel and slid two more pellets into the right front pocket of my dinner jacket as Jim discreetly eased open the doors. We were both in full hunting mode, edging forward in our black patent leather shoes and keeping our moves to a minimum, as though stalking the Canadian bush country for moose, or creeping up on elephants in Tanzania, or belly crawling for pronghorn in the bottom of some dry, dusty arroyo in New Mexico.

“Use the doorframe for a rest,” my esteemed co-conspirator instructed as I eased into position.

Check the scope? I thought, but I knew Jim would already have it set perfectly for the distance and terrain.

“There! Two o’clock! Behind that oak,” he whispered, and I picked up the tentative twitch of an ear. The old buffalo…’scuse me, squirrel…took one hop forward as I picked him up in the scope, but quickly disappeared once more.

For a full minute we watched in silence— I with the rifle anchored against the doorframe, Jim backing me up with his laser vision and steadfast encouragement. Even the doves on Miss Linda’s bird feeder seemed enthralled, and just as my arms and shoulders began to cramp, Jim whispered, “Behind the little dogwood.”

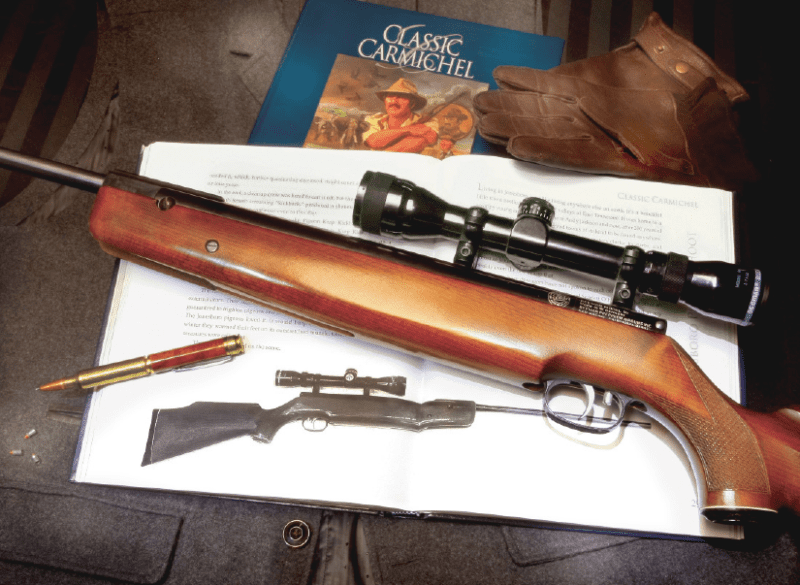

This German-made Feinwerkbau Model 124 has become one of the more famous (or perhaps infamous) pellet rifles ever built.

The first thing I saw was the telltale profile of his back, then his tail as it swished behind him. I took the shot as he stepped clear. He jumped a foot or more straight up and vanished. Easing a fresh pellet from my vest pocket, I quickly reloaded and crept slowly across the savannah…uh, back yard…rifle raised and scope turned down to its lowest setting in case there was a charge. Easing into the woods, I inched three yards, four yards, five yards forward toward the little dogwood and found the crusty old miscreant at its base, belly up and dead as a hammer. I left him there as a warning to any of his brethren who might have their own designs on Miss Linda’s bird feeder.

Our limo was waiting in the big circular drive, and dinner that evening was a delight. The Mahler-Besse Bordeaux was pure perfection, and the company was even better.

The ladies carried on a spirited conversation, while Jim and I reveled in our hunting prowess and the assurance that Linda’s feeders were now safe from assault. It was as lovely an evening as I have ever enjoyed, and when Jane and Carly and I got home that night, I couldn’t sleep.

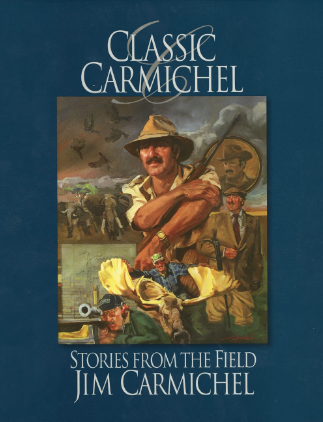

So I did what I always do on nights like this—I selected a good book and settled in next to the fire. The book I chose was, of course, one written by my legendary squirrel guide.

Aptly titled Classic Carmichel, the book was filled with stories of his hunts from around the world, for everything from lions and elephants and crocs in Africa, to ibex and Armenian sheep in Iran, to moose, caribou and pronghorn in North America. There were tales of tyruka from the Andes, tahr and chamois from New Zealand and wingshooting stories from the distant Himalayas to the nearby Jonesboro courthouse. The story I selected was “The Great Jonesboro Pigeon Shoot.”

In all the annals of great outdoor literature, there has never been anything that compares with “The Great Jonesboro Pigeon Shoot,” the tale of…well, I can’t begin to describe it; you’ll just have to read it for yourself. And right there in the middle of the chapter was a two-page-spread photograph of the German-built Feinwerkbau Model 124 that he’d used in the story.

To my amazement, it was the same gun I had used earlier that evening to slay the recalcitrant squirrel.

To think that I had now hunted with the same rifle that Jim Carmichel had used in this classic piece of American hunting literature was overwhelming—not to mention the fact that Jim himself had been my guide! I checked my watch. It was 2:47 a.m.

I wanted to hasten back to Jim’s house and go poking around in the woods with my flashlight. I wanted to retrieve that old bushy-tail bandit from the base of the little dogwood where his pilfering career had come to such an inglorious end. I wanted to rush him to my taxidermist the next morning and have him do a full body mount, or perhaps even make a squirrel-skin rug from his thieving hide—complete with one of Miss Linda’s crunchy sunflower seeds clutched firmly in his teeth.

But in a sudden fit of self-preservation, I realized that I wasn’t the only hunter involved in the old squirrel’s demise, and that my distinguished guide and master of the manor is a far better shot than I will ever be.

So I turned off my reading lamp, trundled down the hall to bed, and closed the proverbial book on the whole sordid episode.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form—until now.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form—until now.

Classic Carmichel features nearly 400 pages of hunting adventures and firearms expertise by Carmichel, widely acknowledged as one of the foremost experts on sporting arms. Carmichel’s exploits and prowess had no equal during what is arguably the Golden Age of international hunting and shooting. These are not just stories by a well-traveled adventurer—they are pure literature, written with a style and eloquence that deserve inclusion in any collection of great outdoor books and writers. Buy Now