But I found a way to beat the odds. If you know someone who is all about muskellunge and who has a cottage on an iconic muskie water, you’re halfway there. And if your friend knows someone who has spent 42 years on the same lake chasing these great fish, and is willing to guide you, now you’ve tipped the scales, lowered the odds and the equation is slightly in your favor. But the king of freshwater gamefish is still a long way from your net.

For more than four decades I have been an avid collector of duck and fish decoys. Through this venue I met Jon Deeter who, along with Gary Guyette, owns the country’s oldest and largest decoy-auction firm. I was lamenting my former muskie woes to Jon several years ago and was surprised to learn that he had a cottage on New York’s Lake Chautauqua where he caught muskies on a regular basis. When he invited me to be his guest the following summer, he didn’t have to ask twice. Then he told me about his friend, Captain Larry Jones, who has been chasing muskies on the lake for nearly a half-century. Larry has made a science of studying these magnificent fish; they’re like extended family to him. Martha and I could stay in Jon ‘s wonderful cottage on the lake where Captain Larry would mentor me for three full days.

We booked the trip for the summer of 2012, but bad luck came at the outset. The month of July proved extremely warm and a dense bloom of green algae covered the lake. Captain Larry predicted the fishing would be poor and suggested we come the following summer. We bought a second pair of airline tickets for July of 2013 and reset all arrangements.

Then more bad luck. A few weeks before we were due to leave, my heart went into serious atrial fibrillation, flutter and tachycardia. My cardiologist scheduled me for an ablation to fix the problem. The operation was successful, but my hip was ablated along with my heart. I knew that catching a muskie was hard, but this was trying my patience.

We rescheduled for 2014. After losing four airline tickets, we decided to drive up from Georgia. This third attempt appeared lucky for us because the weather and lake conditions were ideal. Martha and I reached Lake Chautauqua after a two-day drive and met Jon at his cottage where he gave us a quick overview of the lake and then handed us the key. He was off to New Hampshire to arrange a decoy auction for the following week.

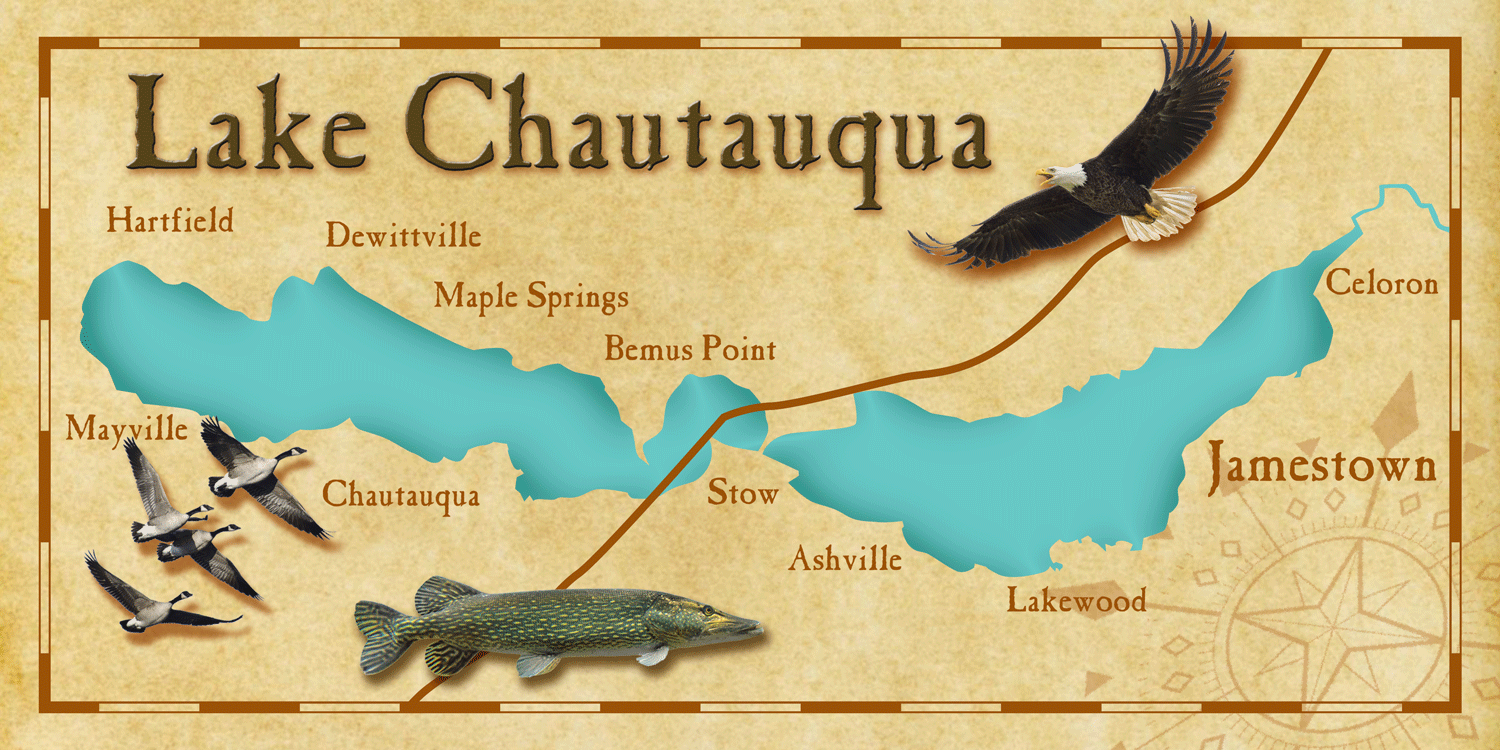

Formed by glaciers 15,000 years ago, Chautauqua is one of several finger lakes in the western-most part of the state. Bordered by the small town of Mayville on the north end and Jamestown on the south, the lake is 17 miles long, with 21 square miles of surface area. Chautauqua is shaped like an hourglass with two long basins, one on each end. The north basin is nine miles long with an average depth of 26 feet and the south basin is eight miles long with a mean depth of 11 feet.

Newberry caught this 32-inch muskie, his first ever, while trolling in 18 to 25 feet of water.

Right. This is a lot of information to throw at you, but if you’re interested in muskie fishing, all of this is important to your success. Muskies, along with northern pike and pickerel, belong to the Esocidae or pike family. Northern pike will occasionally hybridize with muskies, producing the tiger muskie, so named because of the distinct vertical bars on its sides. Many hatcheries have produced this pike-muskie cross and the fish have been widely stocked across the northeastern United States . But the tigers have a shorter life span and do not reach the size of purebred muskies. What’s more, tiger muskies cannot reproduce, which keeps them from breeding out the pure strain of muskellunge—a good thing.

The muskie is the king of freshwater fish–the apex predator. They will eat anything, including each other, and when hooked, they have greater stamina and fight harder than pike. They probably account for the worst success rate in freshwater fishing. Just to have a muskie follow your lure is considered good, like getting one jump out of a tarpon before it throws the hook. The world-record muskie, 69 pounds, 15 ounces, was caught in the St. Lawrence River. To catch a 50-inch fish is extremely rare and most muskie fisherman never even come close to that standard.

Pike occur naturally at northern latitudes throughout the world, but muskies are native only to North America. So it’s our gamefish. Both species prefer cool water, but their temperature preferences are significantly different. Muskies flourish in water from 65 to 72 degrees while pike favor much colder water, from 50 to 55 degrees. Some of New York’s finger lakes are deeper than Chautauqua and so their waters are much colder. Northern pike thrive in these waters, but not muskies. Chautauqua’s shallow depth provides an ideal temperature gradient for muskies in different stages of their life cycle. This biological factor is a major component to the lake’s long and storied history as an iconic muskie fishery.

The first permanent settlements on Chautauqua occurred in the early 19th century. By 1900 spearfishing through the ice had severely depleted the muskie population. But hatchery efforts pioneered on Chautauqua beginning in 1887 ultimately saved the lake’s muskie population. The hatcheries took the science of muskie rearing and stocking to a new level, which, along with harvest restrictions, eventually established a healthy population of the big fish.

In 1925 the daily limit on Chautauqua muskies was restricted to two fish, and in 1941 a Iimit of five fish per year was imposed. A 40-inch size restriction was approved in 1990 and remains in effect today. But the most positive outcome has been the catch-and-release philosophy that nearly all anglers adhere to today.

“It’s the king of freshwater fish. It’s a beautiful and unique animal. It gives you one hell of a fight. So why not release this wonderful creature and let him return to his home in this special place. You will feel better for doing it.” Such is the predominant thinking among most muskie anglers today.

So there I was-poised, ready and confident. Martha and I were enjoying a leisurely drive around the lake when I stopped at a local tackle shop to buy a three-day license. The owner was a good-natured chap who told me about his friend who just spent two days on the lake without a single strike. So maybe I wasn’t quite so confident. But then he didn’t have a guide who was a bonafide muskie whisperer.

Captain Larry pulled up to Jon Deeter’s dock the following morning, and Martha and I stepped on board his 21-foot Tracker. Larry prefers trolling because it enables you to cover a lot of ground, though we would also do some casting with big plugs.

Having fished the lake for so many years, Larry obviously has a number of favorite areas, each based on temperature and prevailing weather systems, water depth and cover, and especially wind and barometric pressure.

After a short run from the dock, we reached one of his predetermined spots and right on cue his depthfinder was marking schools of baitfish with larger predators below them. A rising or falling barometer will often stimulate a feeding cycle, and we had a weather front moving across western New York. Everything was right but all muskie fishermen know that success even in the best of times remains only a remote possibility.

Newberry hooked both fish on this broken-back Wiley Musky King Jr plug.

We began trolling with 60-pound braided nylon over lead-core lines on 330 Penn reels. Tied to our five-foot, 80-pound flurocarbon leaders were 3-ounce, broken-back Wiley Musky King Jr lures running 18 feet deep in 2.5 feet of water. Muskies nearly always strike from below, and Captain Larry expected them to be in deep water under the baitfish.

After trolling all morning without a strike, I put the rod in the holder while I dug a sandwich out of the cooler. You know the punch-line. This is when it always happens.

The rod whipped downward and the drag began whining as line peeled off the reel. I grabbed the rod just as the fish surfaced and wallowed violently, trying to throw the plug. Then he made a short run and once again thrashed wildly on the surface. By the time Larry and Martha had reeled in the other lures, my muskie was giving up line. After a final jump just behind the transom, he was close enough to be netted.

Captain Larry eased the large net under the fish and dislodged the rear treble hook implanted in the lower jaw, all while keeping the fish in the water. Martha grabbed the camera, and I lifted the beautiful creature out of the water for a quick measurement and three photos. Then we slipped it back into the water where it recovered in a few seconds and swam away.

Just like that I had my first muskie—a beautiful 32-inch fish with lots of spots and an olive background. Best of all, a clean release. It was a long time coming, which like my lion in Africa, made it that much better. I thanked Larry profusely and finally enjoyed my sandwich.

That was our only strike of the day and we retired from the lake in late afternoon. I decided to do some casting around the shoreline the last hour before dark and had one heavy strike on a Rapala. But after a short run the hook pulled out. My guess was that a bass had hit the plug.

Martha went shopping the next morning so I met Larry at the dock alone at 7 a.m. The previous day’s front had moved on and the lake was very calm—not a good sign. We tried two of Larry’s favorite spots at the north end of the lake but with no luck. The depth-finder showed the baitfish in tight schools, indicating they were not being molested.

At noon we headed to the south end where Larry often had luck with smaller muskies that were more likely to feed under less-than-favorable conditions. But the shallow water there had a film of green algae on the top. We worked the spot for an hour before giving up.

I saw a large muskie lying in a weedbed and another rolled sluggishly on the water, but neither fish showed any interest in our plugs. Slowly we began trolling back toward the deeper north end where the surface was still placid and the sky clear. We’d fished another two hours when I noticed a bank of cumulonimbus clouds building in the west. I felt a breeze across my face and Larry checked the barometer. It was rising slightly.

“It’s not much change, but things might pick up in a while,” he said.

At 2 p.m. the phone rang. It was Jon Deeter calling from New Hampshire. He couldn’t stand it any longer and had to know if we were having any luck. I had called him the previous night to tell him about my the 32-inch muskie. He was pulling for me to catch another, and hopefully, larger fish.

I began making excuses. The lake had been calm all morning and the fish were not feeding. I was well into my sob story when my rod almost bent double. Larry screamed, “He’s big…really big, don’t lose it.”

I dropped the phone and set the hook, firmly but not too hard. By keeping the rod tip down and at right angles to the fish, the line remained in the water and helped me to keep tension on the muskie. The drag screamed off the reel as the fish headed away from the boat. He dove and then surfaced, coming halfway out of the water while shaking its head back and forth.

When Larry saw the fish jump, he said, “That fish is close to 50 inches!”

Now I was really excited. The muskie was fighting hard and not giving an inch. I worked him without thinking, using skills acquired from many years of big game saltwater fishing around the world. No, actually, I was just holding on for dear life, pumping slowly to gain line and praying he wouldn’t throw the hook.

The big muskie thrashed on the surface at least a dozen times before he began to tire, his dives and rums becoming shorter and shorter. His head-thrashing jumps were now weaker, but I still panicked with each one, hoping the hook would hold.

Larry had the cockpit cleared by the time I wrestled the fish alongside. I thought the battle was over when suddenly the muskie dove under the boat. I plunged my rod-tip into the water to maintain pressure and soon I had him back to the gunnel. He was so big I thought we’d never get him into the net, but Larry, with all of his experience, handled the job masterfully. I helped hold the landing net while Larry removed the hooks from the muskie’s jaw.

We hefted the fish from the water and placed him on the measuring board where I measured his length at 48 inches. We probably took a few seconds longer than normal getting photographs, and when we returned the muskie to the water he was very sluggish. The muskie floated on his side for a second or two as we held our breath, worried that we’d kept him out too long. The fish struggled to right himself, but only swam a few feet. Neither of us said anything; we were just transfixed on the fish, wishing it to move, willing it back to vitality. The big muskie swam a few more feet and then, with a huge splash of its tail, dove down into the depths.

Captain Larry smiled, saying, “He’s alright…he’s going home.”

I never felt so good catching a fish—and I never felt so good releasing one. I did more than my share of bragging over the next two days, but I knew the real truth. Captain Larry Jones caught the fish. His lifetime of chasing muskies put me in the right spot at the right time with the right tackle and the knowledge to make it all come together. All I had to do was enjoy the final act of bringing the muskie to the boat.

Later, when I told Larry that I’d measured the fish at 48 inches from its nose to the center fork of its tail, he said it probably was 50 inches if measured to the end of the tail fin. Only after developing the photos did we realize the fish had an old scar on its side, perhaps caused by a propeller. In our haste to get it back in the water, we’d missed it entirely.

In the weeks to come, George Strunk from New Jersey, a well-known fish and duck decoy carver, created a life-size replica of the muskie from my photographs. It had been a fantastic experience and a wonderful memory. But I’m still not sure I actually earned it. After all, I only made three trips and a total of 12 days of fishing before I caught this great muskellunge. And remember, it’s the fish of 10,000 casts.