It was about 5:15 p.m., 108 miles northeast of Oran, I remember, when the starboard gunners shouted, ‘’Torpedo off the bow!” The helmsman tried to swing her so the thing would run parallel to us, but the old bucket was bottom-heavy with about 9,000 tons of high explosive and she was sluggish as a sleepy sloth. Whatever it was took a long time coming, but not long enough to dodge it. As I recall, I didn’t pray, even though I had seen that afternoon, and on other days, what happens to a ship that gets smacked with a crawful of high ex. I felt a vague regret over the fact that getting blown up at the age of 27 left a lot of pleasant things undone, and that was about all.

Whatever it was hit us with a dreadful crash. The deck plates popped and spouted flame. The ship took a list, and was knocked heavily off her course. The feeling then was impatience that she didn’t blow and get it over with. But no last-minute consignments of soul, no death-brink stammers of apology for what had been a short but gaudy life amongst the shattered Commandments. She didn’t blow. And I uttered no prayer of thankfulness. I just figured that if there wasn’t enough sincerity in me to pray ahead of it, there wasn’t much point in praying behind it. The Lord and I did little business together in those days. It was more or less as if we had been introduced by the wrong folks.

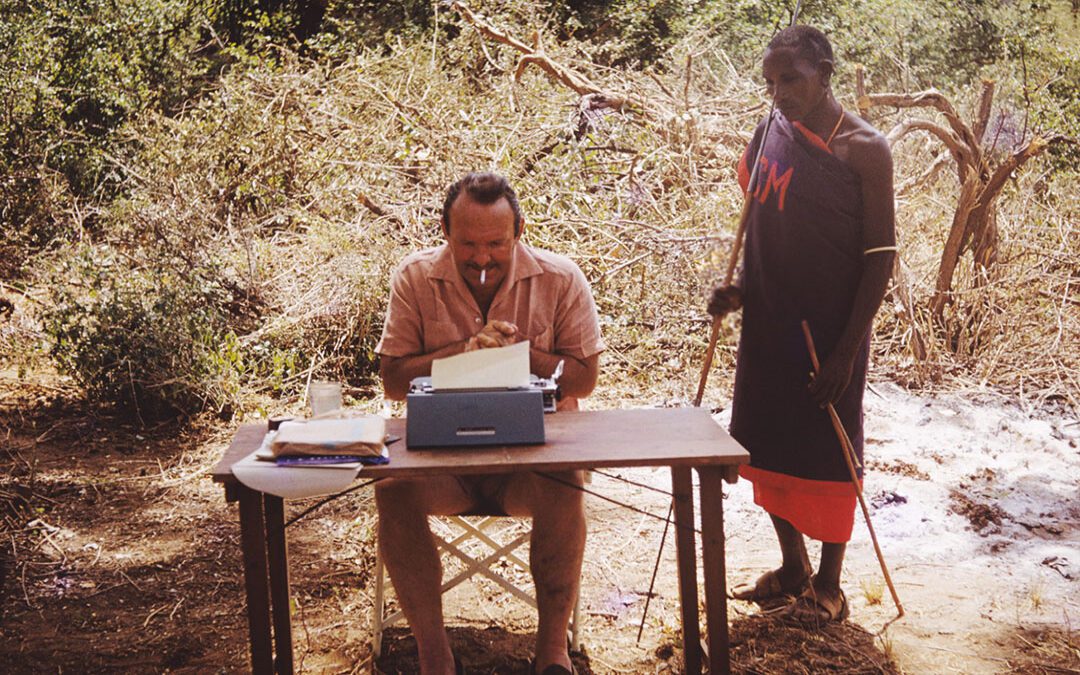

If we can flash forward about nine years, now, I will tell you about a wordless prayer I said. I said it through my pores, sitting in a grove of trees in Tanganyika, East Africa, hard by a crocodile-infested river called The Little Ruaha. There wasn’t anybody around at the time but the Lord and me and some wild animals. I didn’t make any sort of formal speech out of it. Just told Him thank you very kindly for not blowing up the ship that day in the Mediterranean, and for letting me live till this day. It was a little late coming, this thank-you note, but I never meant anything more vehemently. And so far as formal religion goes I am a very irreligious fellow, who smokes, swears, drinks whiskey, ogles girls, and at that very moment was paradoxically interested in killing things.

I was very grateful to be alive, at that moment, for I was alone in the nearest thing to the Garden of Eden I ever expect to see. We had stumbled, while on safari, onto a piece of land which had largely been untrammeled by human feet, and uncontaminated by human presence. The exact location remains a secret. The place was too good for man to louse up. Its keynote was perfect peace.

We were out after kudu—greater kudu—one of the more elusive and possibly the most beautiful of all African game. He is as big as a horse and as dainty as his tiny cousin, the dik-dik. He has enormous backswept upcurling horns that completely spiral twice, ending four or five feet from his skull in shining ivory tips. His coat is delicate grey, barred in white, and there is a chevron on his nose, and his heavy neck wears a long dark mane. Also he is ordinarily twice as wild as any animal, save possibly the bongo. A man is lucky to see one kudu in many months of hunting.

Here the kudu were comparatively as tame as the little Thomson gazelle. I suppose we saw 60 or more in two weeks, and might have shot 20 if we counted the immature bulls. The cows were as tame as domestic cattle, nearly. I shot one kudu bull, because I wanted the trophy badly. The rest of the time we just looked around.

We marveled. Here was country as the first man saw it. We were camped along the river beneath a vast grove of acacia. It was like living in a natural cathedral, to look upward in the cool, created by the flat tops of the giant trees, with the sun dappling here and there to remove the dank darkness of moist forests. It reminded you of sunrays streaming in through the stained glass of a church window. The straw beneath the trees had been trampled flat by all the generations of elephants since the first elephant. The silence was unshattered by traffic sounds, by the squawk of radios, by the presence of people. All the noises were animal noises: The elephants bugled and crashed in the bush across the little river. The hippos grunted and the lions roared. The ordinarily elusive leopards came to within 50 yards of the camp, and coughed from curiosity. The hyenas came to call and lounged around the tents like dogs. Even the baboons, usually shy, trotted through the camp as if they’d paid taxes on it.

The eland is a timid antelope, a giant creature who’ll weigh up to 2,000 pounds, and who almost never stops moving. He is as spooky as a banshee, and unless you chase him on the plains in a car, a couple thousand yards away is as close as you’re apt to get. Here the eland came in herds, walking inquiringly toward you. The same applied to the big Cape buffalo, who ordinarily snatch one whiff of man-scent and shove off. The buffalo walked up to us here, their noses stretched and their eyes placid and unafraid. We watched one herd of a hundred or so for half an hour, and finally shooed them into the bush.

The impala, lovely, golden antelope with delicate, lyre-like horns, are usually pretty cheeky little cusses, but here they were downright presumptuous. As we drove along the trails in the jeep, we would have to stop the car and drive them off the path. They leaped high above the earth for sheer fun, not from fear, and one little joker actually jumped completely over the car—just to see if he could, I suppose.

Even the crocodiles seemed unafraid. They slept quietly on the banks, and didn’t bother to slide into the water at our approach. The guinea fowl, usually scary birds, were as tame as domesticated chickens. We must have seen at least 3,000 one morning, and they neither flew nor ran to the nearest exit. They walked with dignity.

This place had been seen only by one other safari, and was not despoiled by natives. The locals lived 18 hard miles away, and they were not a tribe of hunters. They grew crops and grazed cattle, and robbed wild beehives for honey, and generally did not even tote the customary spear, which is as much a part of native equipment as the umbrella is to the Londoner. One grizzled grandsire, 18 miles away on The Big Ruaha, told us solemnly that he had lived there all his life and had never seen a kudu. We saw 14 that day.

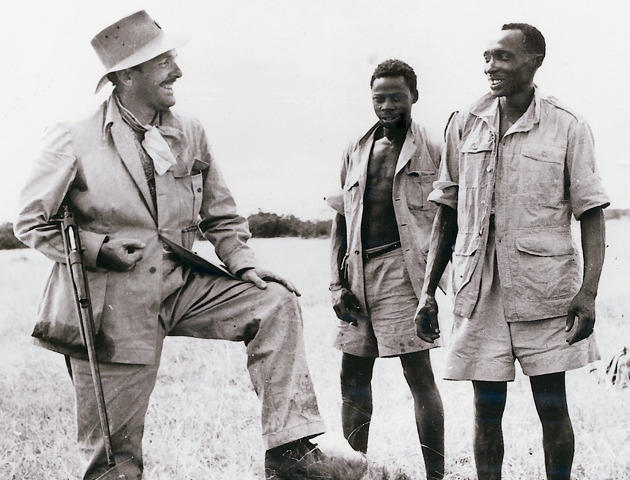

You felt that here was a capsuling of creation, unsoiled, unspoiled, untouched by greed or selfishness or cruelty or suspicion. The white hunter, Harry Selby, whose life has been spent among animals, out of doors, gasped continually at the confidence and trust displayed by the profusions of game. We didn’t want to shoot; we didn’t even want to talk loud. Here you could see tangible peace; here you could see the hand of God as He possibly intended things to be. We left the place largely as we found it. We felt unworthy of the clean, soft blue sky, of the animals and birds and trees.

It was not until we found this camp that I became aware of what had happened to me in Africa. It had been happening daily, but my perceptions had been so blunted by civilized living that I had somewhere lost an appreciation of simplicity, had dulled my sensitivity by a glut of sensation and the rush of modern existence. All of a sudden I was seeing skies and noticing mountains and appreciating tabulating birdcalls and marveling over the sheer drop of the Rift and feeling good. I was conscious of the taste of food and the sharp impact of whiskey on a tired man, and the warmth of water in the canvas bathtub, and the wonder of dreamless sleep. I was getting up before dawn and loving it. I was desperately anxious to win the approval of the blacks who made up my safari—me who never gave much of a damn about presidents and kings. I was feeling kind, and acutely alive and very conscious of sun and moon, sky and breeze, and hot and cold.

This has to be a paradox, because my primary business in Africa was killing. I was there to shoot. And I shot. I shot lions and a leopard and buffalo and all the edible antelopes and all the good trophies I could rustle up. But I never shot needlessly and I never killed anything for the sake of seeing it die. We killed for good trophies, and we killed to feed 16 hungry people. Killing does not seem wrong in Africa, because the entire scheme of living is based on death. The death of one thing complements the life of another thing. The African economy is erected on violence, and so there is no guilt to shooting a zebra that the lions will have tomorrow, or a lion that will eventually be a hyena’s breakfast when he is too old to defend himself against an ignoble enemy.

This is a hell of a way to write for a professional cynic, but you see I’m not really cynical anymore. What has wrapped us all in a protective armor, an insulation against honest stimulation, has been an artificiality of living that contrived civilization has thrust upon us to the detriment of decency.

Things are simple in the African veld. You is or you ain’t. You are a courageous man or you are a coward, and it takes a very short time to decide, and for everyone you know to detect it. You can learn more about people in three days on safari than you might run down in a lifetime of polite association under “civilized” circumstances. That is why very few foreign visitors are speaking to each other when they finish a long trip into the bush.

There is no room for selfishness. A safari is as intricate as a watch. It is pared down to the essentials of good living—which is to say food, transport, cleanliness, self-protection, and relaxation, or fun. It has a heavy quotient of hard work, in which everyone has a share. It is like a ship on a long cruise, in that respect. There is a thing for every man to do, and if he fouls off his duty the failure affects everybody, so everybody’s hurt. A sloppy gunbearer who lags behind can get you killed. Indecision on your part or the part of any vital member of your party can get you killed. Cowardice can get you killed. Lack of caution can get you killed. You shake your shoes each morning on the off chance a scorpion has nested in your boot . . .

When you live around phonies long enough, when your life is a vast and complicated cocktail party of communication, pose, frustration, confusion, pressure, refinement, and threat of indistinct doom, you can forget that the human body is a very simple organism with very simple demands. It does not take much to amuse a monkey, but we have seemingly overendowed ourselves with playthings, with extraneous fripperies we call necessities, with gimmicks, gadgets, gizmos, and distractions that completely obscure the basic truth that a night’s sleep, a day’s work, a full belly, and a healthy elimination is about all a human organism needs for satisfactory existence. The refinements come later, of themselves.

I find today, to my dismay, that while I live in New York in an approximate palace—freshly decorated, at God knows what cost in blood, sweat, and money—I was happier in a tent. It kept the rain off me, needed no lease, was easily movable, and did not require air-conditioning. The bed was a cot, and tired as I was nightly it could have been upholstered in spikes without disturbing my rest.

Now I’m back on my old routine of toying with a chop and spending $8,000 for a dinner I don’t want, but I don’t like it. I recall a fellow by the same name who used to pick up a whole guinea fowl and devour it with great enthusiasm, and who never cared too much whether the Tommy chops had been cooked sufficiently or not. Cold spaghetti tastes great out of a can. Beer is never better than when warmed by the sun, due to no refrigeration. I read a lot of mishmash about diet—in the words of my friend Selby, the hunter: Gimme meat, and skip the extras. In Tanganyika I ate like a starved cannibal and lost weight. There I was eating to live—not to sell books, not to be entrancing, not to be stylish. I was eating because I was hungry, and was burning up enough of what I ate to keep me thin enough to climb a mountain or crawl through a swamp.

You realize that a man who earns a living with two fingers on a typewriter has always accepted the A&P, the local supermarket, the utilities company, the water works, the central heating, and the highway department as part of his life. All of a sudden, save for a few conveniences, I was right back with the early man.

If we wanted light we either built a fire or turned on a very primitive lamp. Fire we always needed, if only to fend the hyenas off tomorrow’s dinner, and always in the starkly chill nights to keep from freezing. So we had to pitch camp in a dry woods close to water. In the absence of a highway department, you have to take a panga and cut your own roads through dense growth, or build your own bridge, or pave the bottom of a stream with rocks you have painstakingly gathered.

I had accepted light, heat, water, roads, and food. Especially food. You flicked a switch, screamed at a janitor, started the car and let her ramble, or picked up the phone and called the grocer. The most intimate contact with food I ever had was when I ate it and when I paid the bill. Now I was for the first time in the bacon-bringing business, which is to say that 16 people ate or don’t eat according to what I could do with a rifle. Not that my wife, the PH, or I would starve, of course. But there were 13 hungry black mouths, used to consuming 10 to 12 pounds of meat a day—each—wondering what goodies Bwana was going to fetch home that day to plug the aching void. By goodies they meant nyama—meat. Zebra meat, eland meat, buffalo meat, any kind of meat. I was the Chicago stockyards, the slaughter pens, the corner delicatessen in their simple and direct minds. This was a new thing. I hunted for it, and I found it, and I shot it, and we butchered it, and then we ate it. What we didn’t eat was made into biltong, dried meat or jerky. The hyenas, the jackals, the vultures, and the marabou storks cleaned up the odds and ends.

There is a neatness to Africa that needs no sanitation corps, no street-cleaning department, no wash-down trucks. What the hyenas and jackals don’t get the buzzards get. What they don’t get the marabou storks get. What else is left around the ants get. There is no garbage—no waste.

Maybe that’s one of the things that hit me hard. No waste. Back home I seem surrounded by waste—waste of money, waste of time, waste of life, waste of leisure, mostly waste of effort. Away out yonder, under the cleanly laundered skies, there seems to be a scheme that works better than what we have devised here. There is a dignity we have not achieved by acquiring vice-presidencies and a $50,000 bonus and planned economies and the purposeful directorship of the world.

The happiest man I ever knew is named Katunga. He is an old WaKamba, whose filed front teeth have dropped out. His possessions are four wives, a passel of old children, young children, and grandchildren. And pride. Katunga is known as Bwana Katunga to white and black alike, because Katunga is the best skinner of animals in the whole world. He achieved his title because he once approached Philip Percival, the now-retired dean of all white hunters, and spake thusly:

“Bwana, I see that all white men are called Bwana. Bwana means lord, or master. Now I, Katunga, am an atheist, because my father was good enough for me. But to be called Bwana means that a man is master of something, and I am master of my knife. I am the best skinner in the world. Why cannot I too be called Bwana Katunga?”

“Jambo, Bwana Katunga,” Mr. Percival said, and Bwana Katunga he has remained. He sings as he skins. He is a happy man, with a sense of humor, and he has never seen Dagmar or Milton Berle, and he disdains a gun as an unworthy weapon compared to a knife. Nor does he pay a tax or fret his soul about extinction. Death holds no horror for him.

One day just before I left East Africa I heard Katunga speaking more or less to himself as he flensed a Grant’s gazelle I had shot. He was surrounded by his usual clique of admirers, for Africans are great listeners.

“I am an old man,” Katunga said. “I am not so very long for safaris. Someday soon I will die. But when I die—when I, who am now called Bwana Katunga, die —I will have left my mark. The safaris will pass my boma. They will see my houses and my maize fields. They will see my wives and my children. They will see what Katunga has left behind him, and they will say: ‘King-i Katunga lived there!’”

And true enough, Bwana Katunga will have become king, since he realizes his worth and anticipates it before time awards it to him. Not many captains of our industry can say as much.

The best man I ever met, white, black, or varicolored, is named Kidogo. Kidogo is a Nandi boy, about 28 years old, who was my gunbearer. He is rich according to his standards. He has wives and children and herds of cattle and grainfields. He has been to English-talking school and it has neither made him a scornful African nor a wishful Englishman. He will work harder, give more of himself to the problem at hand, sleep less, complain less, be more humble, more tolerant, and more efficient than any “civilized” person I know. With it he retains a sense of humor, too, and a vast pride in himself as a man. He hunts as a gunberarer for the best hunter in the business only because he loves the hunt and he loves the hunters and he loves the business of being with Mungu, which is God, no matter how you spell it or conceive of it.

I feared the scorn of Kidogo more than ever I feared the wrath of God or man, and it pleased me that finally he approved sufficiently to make jokes with me. A joke from Kidogo was accolade enough to make my year. It told me I was a fairly decent fellow, worthy of association with a superlatively brave man, a tolerant man, a good man. Apart from the joking compliment, he showed no surprise when his bossman casually assumed that I would join them in a happy little adventure called “pulling the wounded buffalo out of the bush.” Kidogo tracked the blood spoor for me, with his life on the line ahead of me. He seemed confident that his life was in good hands, since he had no gun. Adam, the other tracker, showed the same sort of confidence in Selby, and to be accorded a similar consideration as Selby was the deepest bow to my ego I ever experienced. Because Selby is the all-time pro at standing off charging buffalo at four feet.

I still thrill, from time to time, about the dedication to danger that was given me by three relative strangers. “Clients” are generally told to wait in the jeep until the dirty business of finishing off a wounded, dangerous animal is complete. If they are “good,” or nonabrasive clients, they might be asked if they care to join in the dubious fun of extracting a sick, sore, and angry animal from his bastion in the thorn. We hit a buffalo hard. Twice he went to his knees, but nevertheless recovered and took off with the herd.

“Let’s smoke a cigarette and give him time to stiffen,” Selby said. We smoked the cigarette, Selby, Adam, and I. Kidogo doesn’t smoke.

“Well,” Selby said, directly to me, crushing out his smoke, “let’s go and collect the old boy.”

No ultimatum to wait in safety. No request as to whether I wished to play. It was assumed by Harry Selby, who is half buffalo and half elephant, and two lean blacks who live by danger, that I was naturally going to tag along. No Pulitzer Prize, no Congressional Medal of Honor, would ever give me the thrill I got that day out of casual acceptance as an equal.

You see, there is a thing about the buffalo. He is a very naughty creature, as Selby might understate it. He is so bloody awful, horridly, vindictively naughty, after he has been hurt that he is almost impossible to kill. He will soak up bullets that would stop elephants cold and still keep coming. He can run faster than you can. He can turn faster than you can. He will hide if possible and take you from the rear, and he can hide in bush that wouldn’t cover a cat. He weighs in the neighborhood of 2,500 pounds. He will hook you with his razor horns—he charges with his head straight out and his eyes open—and then he will go and pick you up from where he has thrown you again. When you cannot move he will jump up and down on you with feet as big as flat irons and as sharp as axes. He will butt you and kneel on you, and if you climb a tree he will stretch that big snout up and lick the flesh off your feet with a tongue like a rasp. When he is wounded and you are up against him there is only one logical development. You die, or he dies, because he will not run away. He just comes, and comes, and the brain shot sometimes won’t stop him. Most wounded buffalo are killed within a hand’s reach. The starkest fear I have ever known was given me by buffalo, until the fear became a fascination, and the fascinations an addiction, until I was almost able to observe myself as another creature, and became bemused by my own reactions. I finally courted buffalo as a hair shirt to my own conscience, and almost would have been interested objectively to see how many possible ways there are to be killed by one.

On this trip to Africa, and in my association with Selby, Kidogo, Adam, and a few lions, leopards, buffalo, and other vindictive insects, I had the opportunity to find out about courage, which is something I never acquired from the late war. I know now that I am a complete coward, which is something I never would admit before. I am the kid with the dry mouth and the revolving stomach, the sweaty palms and the brilliant visions of disaster.

But cowardice has its points, too. There are all gradations of fear, and the greatest gradation is the fear of being known to be afraid. I felt it one day after a lengthy stalk through awful grass after a wounded buffalo. When I finally looked at him, and he looked at me, and there wasn’t any tree to climb and no place to hide, I was the local expert on fear. At less than 50 yards a buffalo looks into your soul.

I unlimbered my Westley Richards double-barreled .470 and let him have it where it hurt. Then I went off and was sick. And then for the next several weeks I had to force myself to inspect his relatives at close quarters. I was frightened of embarrassing Harry and Kidogo and Adam by my own cowardice, so my cowardice conquered the minor cowardice, which only involved dying, and so we went and sought the buffalo. Ditto lion, leopard, rhino. Likewise snakes. A small cobra is very large to a man who fears caterpillars.

I learned, on this expedition, about such things as grass, and its relations to rain, and its relation to game, and game’s relation to people, and people’s relation to staying alive. There is a simple ABC here: When it rains too much, the grass grows too high. Also trucks get stuck, but the main point is that when the grass grows too high, you can’t get there from here. You stay where you are, and all the frantic cables from home can’t reach you.

Also when the grass is too high the game is in the hills, and you can’t get to the hills, and furthermore the carnivores that live off the game are out of sight, too, because there ain’t no carnivore where there ain’t no game. The lions and leopards and cheetah can’t operate in the high grass because the Tommies and Grants and zebras and wildebeest know that the carnivore can’t operate in the high grass. And it is an amazing thing that all the hoofed animals drop their young when it is raining so hard that nothing predatory can move much, which gives the young a short chance to stay alive. Me, I always thought pregnant animals went to hospitals when their time came on.

I learned something of females on this trip, too. Such as how the male lion seldom kills. What he does is stand upwind and let his scent drift down. Once in a while he roars. While he is creating a commotion the old lady sneaks along against the wind and grabs what she is sneaking after and then she breaks its neck. And brings home to father the spoils of her effort. We have reversed this technique in this country.

The emphasis on sex is very simple in Africa, having little to do with the citified voodoo with which we have endowed it. Sex is not really a symbol, nor is it hidden, psychiatry-ridden, or obscure. There are two sexes—doumi, the bulls, and manamouki, the cows. They work and they breed and they die. There is no such thing as a sterile man, because the woman shops around amongst the village until she breeds. Breeding is thought to be highly important, since it begets Mtotos, and children of both sexes are highly regarded as both nice to have around the hut and valuable in an economic sense. Neither sex of animal nor human group seems overworried about morality as we know it, or the implications of sexual jealousy as we know it. They get sex, and are content, and do not need a Kinsey lecture to impress its importance on each other. They also have sun and rain and seasons, and if they take the sheep and goats into the hut at night it is to keep the sheep and goats from harm while simultaneously keeping warm. It makes as much sense as tethering a poodle to a restaurant radiator.

What I have been driving at all along is an explanation of why I want to go back to Africa, again and again and again, and why I think Kidogo the gunbearer is more important to life than Einstein or Dean Acheson. It is because I discovered in Africa my own true importance, which is largely nothing. Except as a very tiny wedge in the never-ending cycle that God or Mungu or somebody has figured out. The Swahili say: “Shauri Mungu” meaning “God’s business,” when they can’t figure out an explanation for why it rains or they lost their way to camp or there aren’t any lions where there should be lions.

In Africa you learn finally that death is as necessary to life as the other way around. You learn from watching the ants rebuild a shattered hill that nothing is so terribly important as to make any single aspect of it important beyond the concept of your participation in it. You are impressed with the tininess of your own role in a grand scheme that has been going on since before anybody wrote books about it, and from that starting point you know true humility for the first time.

I believe today I am a humble man, because I have seen a hyena eat a lion carcass, and I have seen the buzzards eat the hyena that ate the lion, and I saw the ants eat one buzzard that ate the hyena that ate the lion. It appeared to me that Mungu had this one figured out, because if kings fall before knaves, and they both contribute to the richness of tomorrow’s fertile soil, then who am I to make a big thing out of me?

It was not so much that I was a stranger to the vastnesses of Tanganyika, which are not dark but joyous. It was not that I was lost in a jungle so much as if I had finally come home, home to a place of serenity, with a million pets to play with, without complication, with full appreciation of the momentary luxury of being alive, without pettiness, and, finally, with a full knowledge of what a small ant I was in the hill of life.

I belonged there all the time, I figured, and that’s why I say I had to go to Africa to meet God.

Editor’s Note: “The First Time I Saw God” originally appeared in the March 1952 issue of Esquire. Copyright 1951 by Robert Ruark; renewed 1979 by the Estate of Robert Ruark. All rights reserved. Permission granted by Harold Matson Co. Inc.