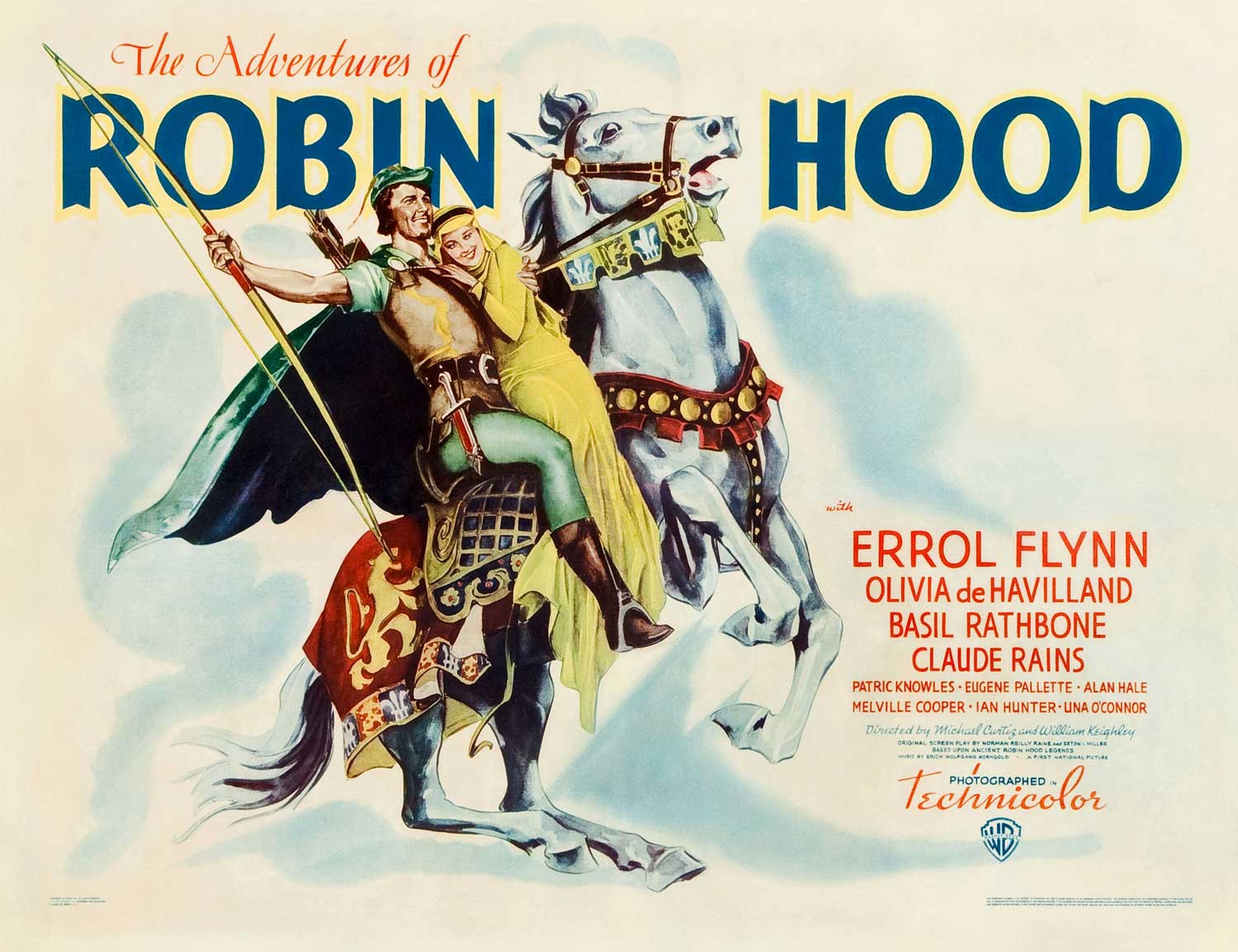

Viewed from the end, an imbedded arrow is an obscenely small mark, cleaving it the stuff of fairy tales. But film director William Keighley wasn’t working on a cartoon. He needed that arrow split. For real. On camera.

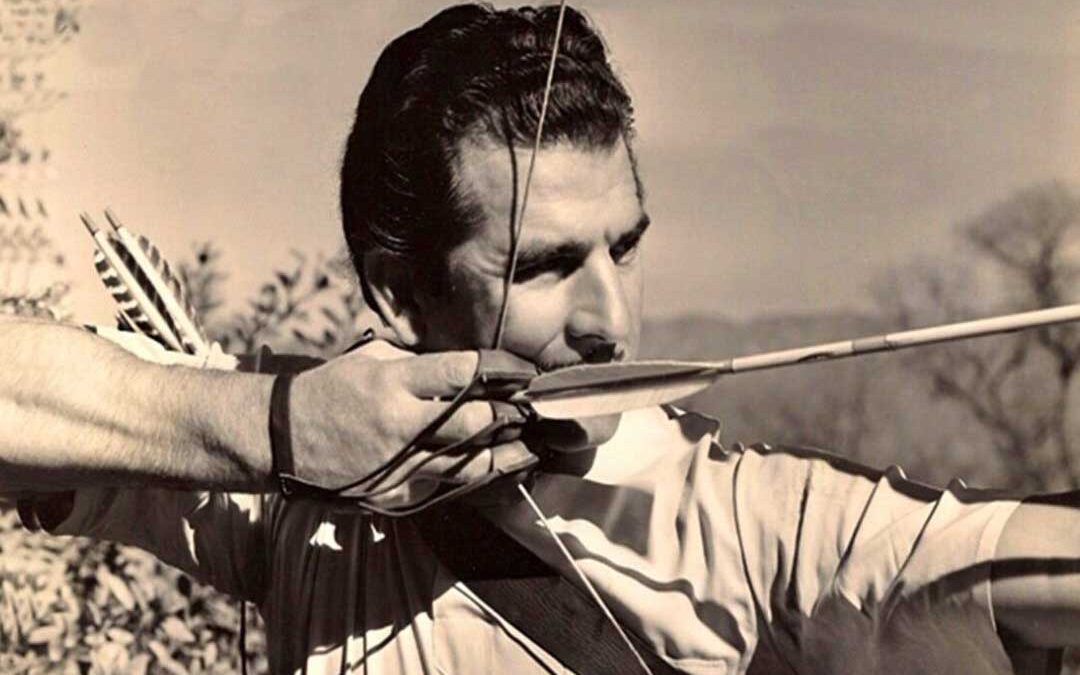

Who better than an archer who shot as if drawing the string came as naturally as drawing breath, whose arrows routinely hit airborne coins and nipped cigarettes from the lips of trembling volunteers?

Howard Hill was born in 1899 on an Alabama cotton plantation. By common account, he was just five years old when a shaft from his oak bow impaled a cottontail. The athletic youth excelled in golf and other sports. But he fell under the spell of the longbow. Soon he was shooting daily. In 1922, on the cusp of a seven-year fling with semi-pro baseball, Hill married Elizabeth Hodges, his high school English teacher. “Libba” encouraged his competitive shooting. In 1925, Hill won the National Flight Tournament, the first of seven titles in a row! In 1928 he set an arrow flight record of more than 391 yards. His 60-inch Osage orange flight bow drew 172 pounds. It launched a birch shaft with 3-inch fletching.

Fascinated by Indian cultures and hunting traditions, Hill learned of both at the knee of a Florida Seminole. The archer tried his hand at bow-making with a lemonwood stave in 1926 and didn’t like the results. But he persevered in his Opa Locka, Florida, shop until 1932, when a newspaperman in California hired him as a physical trainer — and Libba as an academic tutor for his sons. At the Barstow, California, ranch, Hill met and got on well with Ed Hill (no relation). A Ford Model A with oversize tires carried them into the desert where they pestered rabbits and wild burros with their bows.

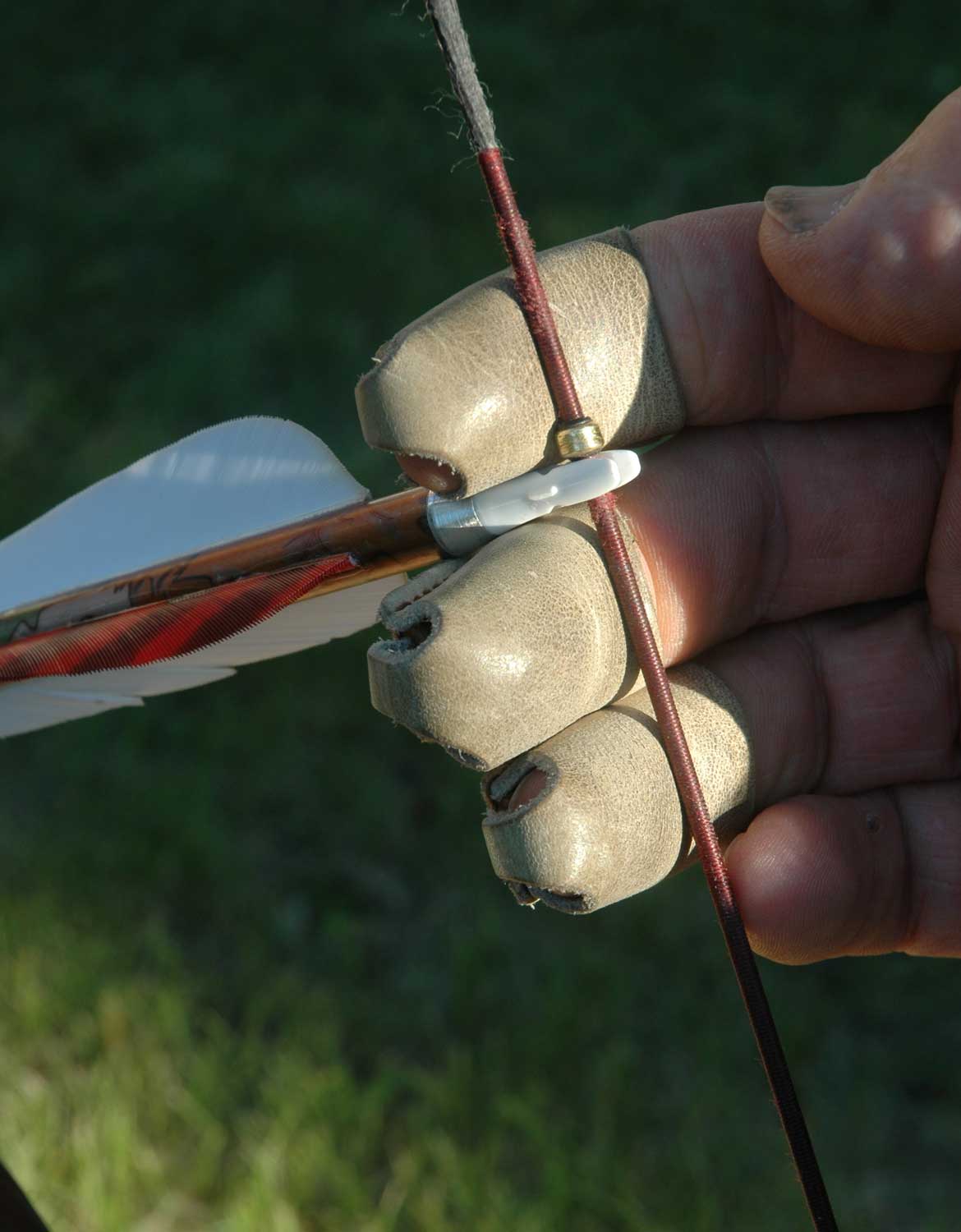

Heavy draw weights prompted Hill to insert turkey quills, whale-bone and nylon in his finger stalls.

A 1925 expedition to arrow a moose in Canada inspired Hill to film big game hunts. He tapped Hollywood for support to produce The Last Wilderness, set in Wyoming. In ’33 he teamed up with outfitter Ned Frost, who had famously guided bowhunting pioneers Saxton Pope and Art Young in their successful quest to shoot grizzly bears. Hill killed a mule deer and a bighorn ram. On the apron of the Rockies, he swung aboard a fast pony, bareback, to arrow a bison Plains-Indian style. The herd he chose was unimpressed by the galloping horseman. A bull turned to meet him. Hill closed the gap with a war-whoop and from mere feet drove a shaft through the beast’s heart.

But it was an elk that truly tested his shooting skill. Spotting a bull at timberline, Hill ran out of cover well shy of bow range. Though a shot was ill-advised, he let fly. The shaft sailed over the elk. After a corrected hold put his second shot low, he sent a fatal arrow through the bull’s ribs — reportedly from 185 yards away.

The Last Wilderness project left the Hills house-hunting in North Hollywood. Partly to promote his film, Hill shot in exhibitions, some later televised. I recall watching him lay a board, its far end elevated, in front of a target. Then he stepped back. Suddenly an arrow dashed from bow to board to the very center of the bullseye! His shafts flew unerringly, to skewer small fruit and pluck even dimes out of the air. He could break two balloons with two arrows, loosed at once — or pop in turn a series of balloons, one inside the other and each smaller, by nicking the outermost. He shot fast enough to put eight arrows aloft before the first landed, once loosing a dozen in 25 seconds.

Hill took Annie Oakley’s stage routines to another level, accomplishing with arrows what she did with bullets. Once, after shooting an apple on the head of an audience volunteer, Hill insisted on substituting a plum. Gamely but with clear apprehension, the young man agreed. Hill’s shaft centered it. “Next, a cranberry,” he dead-panned, pulling one from his pocket. The volunteer fled back into the crowd.

Would he have hit the cranberry?

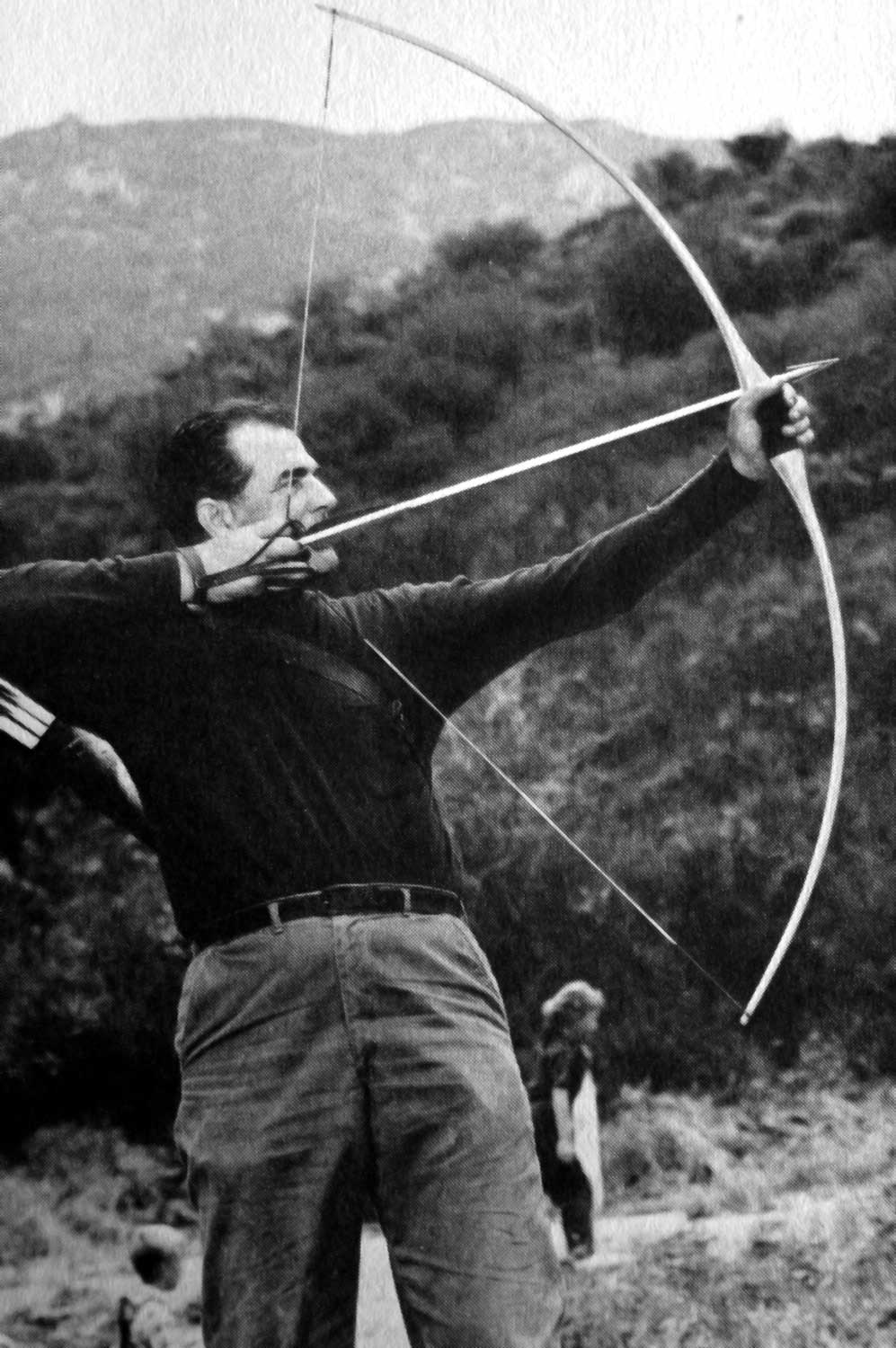

Youngsters like me were convinced Howard Hill could do the impossible. Beyond uncanny accuracy, Hill seemed possessed of superhuman strength. On stage he drew a 110-pound bow to power arrows through 2-inch planks. Once, on film, he steadied his heavier hunting bow against the tug of four Hollywood starlets. Together the comely quartet couldn’t budge the string. Hill took the bow in hand, smoothly drew to anchor and sent a shaft to the bullseye.

The Adventures of Robin Hood brought a new challenge. Director Keighley needed an archer who could shoot for the film’s leading man, Errol Flynn. Splitting an arrow was a difficult but safe part of the assignment. To cleave the shaft, Hill used a crescent-shaped small game head (it would later sever a rope strung to hang Robin Hood). He loosed only nine arrows before getting a usable split on camera, and six of those damaged the imbedded shaft! It was an incredible display of precision — this with imperfect wood arrows!

A more sobering task followed. Hill was to hit small steel plates strapped to the chests of moving horsemen, who would then fall on camera. Worn under clothes, the plates had 3-inch-thick balsa faces to catch the arrows. But Hill noticed that with each stride a galloping horse imparted 9 inches of rise and fall to the target! That vertical bounce made a difficult shot much harder!

Timing also mattered in the shooting of soldiers dashing forward to throw spears. “When a man hurls a spear,” observed Howard, “he must rotate his body. I had to send my arrow the instant the fellow turned his chest to me, because the only protection he had was there! A shaft under the armpit might well have been fatal.”

Action scenes begged quick thinking, faultless cadence. The most daunting of his assignments, he recalled, was a rapid-fire sequence in which, “I had to loose seven arrows quickly, the third into a man as he dashed through a door, the others into its 2-inch-wide frame. Sharp arrows went to the frame, my only target tip to the man. Picking the wrong arrow for that third shot could have been disastrous! Also, the door was constantly swinging open and shut, exposing then shielding a crowd!” Hill had to repeat this sequence when smoke from pots in the banquet hall ruined the first three takes.

During the 1937 production of The Adventures of Robin Hood, Hill’s arrows hit 45 balsa slabs on stunt men. The finished film, in 1938, showed 11. No injuries. Hill was paid $150 a day plus $100 per hit. He appeared briefly in the tournament scene that produced the split arrow. Warner Brothers spent $2.03 million on this film. It earned $3.98 million — big money on the tail of the Depression.

The Adventures of Robin Hood was, and for many of us remains, the defining story of Sherwood Forest and its endearing bandits. Robin of Locksley was played brilliantly by Errol Flynn. Had I not fallen for his co-star, the young and lovely Olivia de Havilland, I might have thought even better of him. Alas, I was no match for the handsome, athletic Flynn, blessed with Hollywood’s magic dust of music, costume and fawning cast. He had it all. And Hill to shoot for him! Olivia would have spared no thought for this ragamuffin kid with a fiberglass bow from a Green Stamp store….

Several movies milking the Robin Hood legend post-date the Flynn-de Havilland epic. Some are animated, some spoofs. A television series appeared during the 1950s. Arguably, none match the 1938 film. But was there a real Robin?

References to this elusive figure span generations with little consistency. John Harrison’s “Exact and Perfect Survey and View of the Mannor of Sheffield of 1637” describes a “Hagges Croft (pasture) wherein is ye founacion of a house or cottage where Robin Hood was borne.” But the Survey trailed well behind early oral accounts. The antics of Sherwood’s Merry Men bring to mind the Norman conquest of 1066. In one tale of that time, men of Kent disguised with tree boughs ambushed William the Conqueror “and drawing their bows” forced him to cede back ancient rights.

The Robin Hood project brought additional Hollywood work for Howard Hill. Directors tapped his talents for other films: Bandits of Sherwood Forest, Elizabeth of Essex, Buffalo Bill, Dodge City and They Died with Their Boots On.

Flynn and Hill got along well. Off the set of Nottingham, they relaxed on Flynn’s yacht, Sirocco. There Hill achieved his goal of arrowing a blue marlin. He “rigged a lily-iron point on a long shaft,” then fastened the head to 80-thread line, spooled into a Von Hoff reel on a shark rod. A great marlin “rose [behind] the skipping bait…. When the camera came up to speed I quickly drew, aimed and loosed the arrow. The head drove just under the dorsal fin….” The marlin turned toward the open sea. Hill played it until both were exhausted. Sirocco’s crew dispatched a skiff to help with the finish, but the marlin came to life in a last rush. “His sword hit dead center of the skiff [and] went through both sides…” — pitching the sailors into the sea!

Ever keen to combine adventure, archery and film-making, Hill brought all three underwater in a quest to arrow a shark. His 1954 book, Wild Adventure, describes this project off Florida’s coast. “I knew positively nothing about underwater gear,” he admitted. As with his early efforts to fashion archery tackle, he improvised, building a water-tight box for his beloved Sinclair camera and “a small diving rig.” He tested both in a swimming pool. Hill found shooting under water difficult, the bow limbs “offered so much resistance.” To nudge the string and give arrows additional boost, he fitted rubber straps above and below the bow handle. “A solid 11/32 dural shaft 6 feet long” gave him 25 yards of reach.

Diving 60 feet, Hill spotted “a long shadow creeping over the white sand….” A big thresher shark “passed over my head no more than six feet away.” Hill drew and gave his target generous lead. The heavy shaft sped forward, passing through the gills and turning the sea red. “I could have made no more perfect shot had I thrown a hundred arrows….” Hill and cameraman George Meggs retrieved their prize.

By modern measure, Hill was no trophy hunter. His lifetime bag, which by rough count exceeded 2,000 animals, included small game and many creatures not considered game at all. He enjoyed hunting wild pigs on California’s coast. He arrowed gamebirds, woodcock to turkeys, and took 20 ducks on the wing. Hill estimated he’d shot 1,500 rabbits. He shot furbearers too, weasels to a wolf. He took alligators, snakes, even trout.

Adventure followed him to Africa, where his chronicles read like fiction. Bow-fishing the riffles of a river in Tanganyika, Hill heard his pal’s cries for help. Slowed by a leg injury from a Jeep accident, Hill found his friend fighting the coils of a python. “Hold that head clear!” he yelled — and promptly sent an arrow through it.

Hill summoned such precision in an eye-blink. Canoeing down a river, he and native paddlers spied a sandbar loaded with crocodiles. They approached silently. At 25 steps Hill’s arrow zipped through the chest of a sleeping bull. The big reptile “leaped straight up … and swapped ends. His great tail caught another croc and knocked him right off the bar.” In the instant before the stricken croc reached water, Hill had another arrow on the way. It struck with a loud clap “just back of the right eye” and pierced the brain.

Hunting lions, Hill spied vultures, then a hyena near thick bush. As he neared the carcass, a growl confirmed it was still a lion’s! “Never in my 30-odd years of hunting … had I felt [so] inadequate.” He backed up fast. The lion came forward, into view. Hill stopped, and so did the cat. When it glanced away, Howard’s broadhead drove into its chest. “Fighting the arrow [put the cat] off-balance….” A second shaft slipped through the ribs “seemingly without slowing” and stuck in the ground several yards beyond. The lion charged. At 15 feet Hill’s third arrow struck an eye and powered through the skull.

A leopard encounter proved lively too. Hill evidently knew he was close to the beast and that it was on the ground. When he spied the cat, he sent a shaft 30 yards to its chest. “He came at me through the grass in fast leaps [and] in a zigzag course.” Hill grabbed one of two arrows he’d readied for a quick follow-up. “I drove a broadhead into his open mouth and down his throat.”

The most widely trumpeted of Howard Hill’s exploits was his downing of an African elephant in February, 1950. Saxton Pope and Art Young had returned from Africa declaring archery tackle (without poison) impractical for hunting animals as big and thick-skinned as elephants. Generous funding from a friend fueled Hill’s attempt to prove them wrong. He would send a 1,700-grain, 41-inch metal shaft with a permanently affixed head from a bow pulling 115 pounds. Other dangerous game was on the docket too. Age 50, the intrepid archer headed for Africa, equipped not only to arrow an elephant but to film the hunt.

Weeks later, his chance came as nine bulls angled toward him in the bush. When the first animal turned, he made a poor shot. The next arrow caught the third and biggest bull perfectly, angling in behind the foreleg to drive 31 inches through the lungs above the heart. The great beast collapsed in four minutes. Tembo, Hill’s resulting film, was translated into seven languages and viewed in 57 countries.

Hunting tales can take on a life of their own. Did Hill really tumble a running rabbit at 147 steps? Shoot quail on the wing? Skewer a duck on a pond 160 yards off? Could he beat a skeet shooter in a clay target contest, bow against shotgun? Light a match with one arrow and snuff it with the next? Such claims beggar belief. But so did his exhibitions, his shooting for Hollywood films, his competitive victories. All those were witnessed by many people. Hill left the field archery circuit after winning 196 tournaments in a row. Why the exodus? He said other archers were grousing. “When they saw I’d entered a shoot, they’d back out or say the scoring was skewed — even when I let others score my shots and collect my arrows!”

Deeply religious, Hill didn’t take his athletic prowess and extraordinary coordination for granted. He acknowledged those God-given talents humbly, then honed them with constant practice. “Every day of my life I have shot,” he declared. “That’s the only way to stay proficient with the bow and arrow.” Speed followed accuracy, always. He worked to make each shot perfect, teasing out inconsistencies and flaws. A center hit was the only acceptable result.

Hill used what he called split-vision aim: focus on the target but with the arrow in view. He drew with a bent bow arm and a canted bow, anchoring into the valley of a missing eyetooth. He was on target as soon as he anchored and released quickly — the prerogative of someone who has sent tens of thousands of shafts. Once, afield with Ted Ekin, he watched his pal draw on a squirrel, then refine his aim to ensure the hit. Ted held and held, until Howard remarked, “Son, if you don’t get some wood in the air, you ain’t gonna hit nothin’!”

In 1957 Hill lent his name to the Shawnee Archery Shop in Sunland, California, partnering there with Ekin and Dick Garver. The next year, after a bamboo-buying trip to Japan, Howard Hill Productions became part of the Sunland enterprise. Its investors then backed Hill in a new effort. Howard Hill Archery expired in 1963 after three years.

Howard’s nephew Jerry Hill succeeded him in business. John Schulz, who in his 20s learned from the legendary archer how to build bows, followed Jerry. As owner of LongBow Manufacturing Company, he later produced the Howard Hill Longbow for Howard Hill Archery. Schulz then opened a shop to build his own American Longbow, clearly on the Hill design.

I bought an exquisite 70-pound bamboo longbow from Shulz.

The Howard Hill label then migrated to the Hamilton, Montana, shop run by Craig and Evie Ekin. Craig grew up in Hill’s shadow. His 1982 book, Howard Hill, The Man and the Legend, includes anecdotes and photographs to inspire any archer. Several photos in this article are from Ekin’s book and used, gratefully, with his permission.

Sifting myth from fact is the historian’s headache. Howard Hill revived the longbow, afield and on-screen. Millions of people otherwise ignorant of archery remember his amazing exploits. Other able archers have since appeared. None have upstaged Howard Hill.

He was an original, a prodigy. John Shulz recalled seeing Hill hit 20 airborne silver dollars consecutively, and seven of nine tossed dimes. He said Howard would shoot against any archer anywhere, on any bet, if he could pick half the targets. “He’d almost surely beat you on yours, and when you got to his half, well….”

Hill was a student of nature, as shown in his books Hunting The Hard Way (1953) and Wild Adventure. His writing shows reverence too for Native Americans who taught him about the woods. He left most of his estate to preachers who’d train evangelists to bring them the Biblical Good News.

Hill died in his birth state of Alabama February 4, 1975. Libba followed just 18 months later. He remains, for those of us who grew up watching him work magic with a longbow, an inspiration. Howard Hill brought an ancient, elegant implement to life. And his unerring cedar shafts skewered the impossible.

What Howard Hill Used:

Hill favored traditional equipment. He preferred the longbow over the recurve, which he said was harder to shoot well. He favored bamboo for his longbows because its fibers ran in parallel, uninterrupted strands. Hill sifted many types of bamboo before he found a Japanese species he deemed suitable for bow limbs. Warning archers not to “over-bow” themselves, he advised hunting with the heaviest bow that was comfortable to draw repeatedly in practice. Years of shooting and routine weightlifting conditioned his body; even in exhibitions he used 85- to 110-pound bows. Once, in his shop, he astonished onlookers who challenged him with a 150-pound bow. Hill drew smoothly to his normal 28-inch anchor — then kept pulling to more than 30! Bowstrings bit deeply into his shooting glove so he inserted turkey quills, then whale bone and final nylon to reinforce the finger-stalls for a smooth release.

While he used Easton XX75 aluminum arrows, then X7s late in his career, he preferred wood and was especially fond of footed shafts. He matched spine after finishing a batch of arrows by shooting all of them into a milk carton set against a sand-pile. He gathered the hits and those that landed left and right into separate bundles.

Most commercial broadheads of Hill’s day lacked the durability he demanded when shot from heavy bows, so he fashioned his own two-blade heads of tough steel. Three times as long as they were wide, they resisted wind-planing and readily split bone. To stabilize arrows quickly in flight, Hill favored three-fletch steering, with 6-inch natural turkey fletch 5/8-inch high. His arrows rode in big shoulder quivers that afforded quick access. Felt or oats in the bottom reduced shuffling and noise.