He slowly pulled the hook, line and cricket toward his cheek, the pole’s tip bending back, and released the missile.

Donald was my father-in-law way back in the ’90s. Or you could say it was the “past century.” He didn’t live to see the new hip millennial century. Donald would agree he really didn’t miss much.

He was born and raised in the South Carolina Lowcountry, a stretch of flat coastal plain between Charleston and Columbia. The region was, and still is, refreshingly behind-the-times, filled with farms, forests, swamps, cricks, rivers and the huge man-made lakes of Marion and Moultrie. These two connected reservoirs were created back in the 1940s when somebody dammed up the Santee River as part the Rural Electrification Program.

Most folks were pretty happy without electricity until word got out. Then everybody had to have some. You know how that goes.

The territory contains a colorful mix of inhabitants. These are go-to-church, salute-the-flag folks with mostly English, Scottish and African ancestries, with their own unique ways of speaking and thinking. And all were raised with a fishing pole and a shotgun in their hands. Or they moved to New Jersey.

It was there in Lake Marion where Donald shared with my sons and me the secret of “cricket flickin’.”

It was pre-dawn when I woke my sons Dan and Sam, just 8 and 6 years old, for a day of fishing with Granddaddy. We’d stayed at his country house down near New Zion, about an hour from the lake. I’m not sure New Zion even exists. I’ve never seen such a town, but it was part of Donald’s mailing address.

After his wife, Ellen, made us a grits, eggs and bacon breakfast, we loaded into Donald’s little Ford pickup with his 14-foot jonboat trailered behind and headed toward the landing.

Halfway there, Donald pulled over at the bait shop in the little town of Manning. After going inside and purchasing a disposable cardboard cylinder filled with about 200 brown crickets and a couple chunks of raw potato, Donald walked over to a barrel filled with cane poles. Each had already been strung with a length of mono line, a red-and-white cork and a gold-colored bream hook.

Donald handed the crickets to the boys, who immediately tried to pull off the top for a better look. I put a stop to that but not before a dozen climbed out, making their escape.

Meanwhile, Donald was holding a skinny 9-foot cane pole out in front of him, sizing it up like a pool shooter trying to judge the straightness of his cue.

But the real test came next, as he took the line in his right hand and pulled it gently, watching the tip of the rod bend toward him. He tugged three or four times before returning the rod to the can.

In five minutes or so, Donald had selected four poles that bent to his liking. I offered to pay since he’d bought the crickets, but he’d have none of that.

Less than an hour later, we arrived at Pack’s Landing, loaded the gear in the boat, backed her in and revved up the little Evinrude. Our destination was a grove of cypress about a mile on the other side of the open water.

“The shellcrackers are beddin’ back in the trees,” he told the boys over the gurgle of the motor. “Wussa shellcwackuh?” Sam the younger asked.

“It’s a big ol’ bream,” Donald replied, taking his hand off the tiller long enough to hold his hands nearly a foot apart.

“Can ya eat ‘em?” Dan the older asked. Dan liked to eat most everything.

“It’s the best eatin’ fish you can catch,” Donald answered. “‘Cept maybe a little three-pound channel cat.”

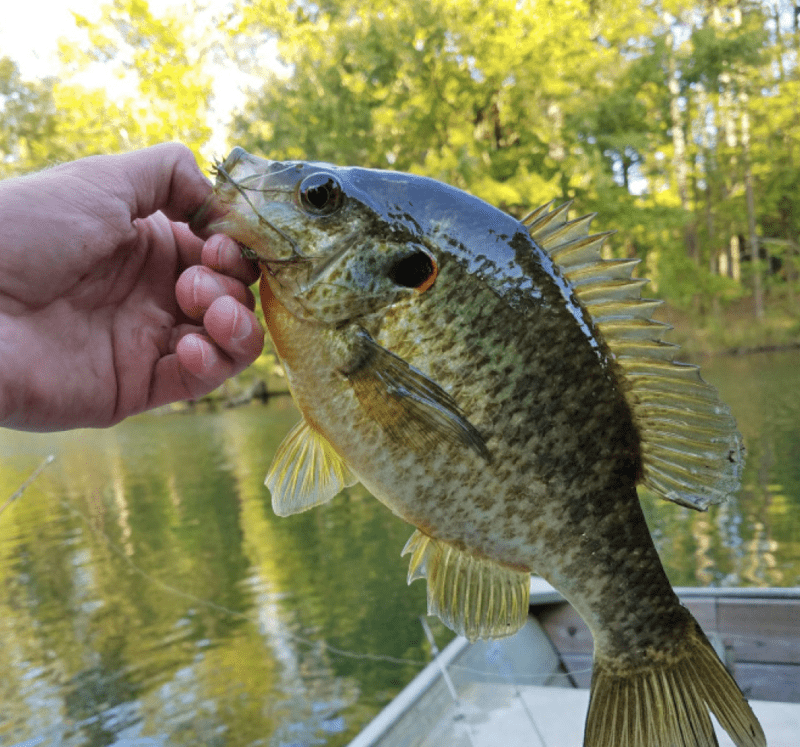

A shellcracker is a beautiful and delicious strain of redear sunfish that gets fat and feisty when spawning in the spring. In the Lowcountry, their favorite place to nest is deep in the dark shallows of cypress groves.

Donald cut the motor as we approached the cypress swamp. I sat on the bow, slowly paddling out of the bright morning sun into the shadowy green forest.

Donald directed me as the trees closed in around us. The water was calm, taking on the deep brown of tannin. Blackwater they call it. We both had to use our hands at times to shove off trees, always on the lookout for moccasins. They love napping on those low-hanging cypress boughs.

“That’s good right there,” Donald told me.

“Tie us off on that limb and let’s flick some crickets.”

“How do we fwick these cwickets?” Sam asked.

“Bout to show you, Sam,” he answered, leaning close to the boys.

I watched as Donald opened the cricket box to expose the little side hole where only one or two can climb out at a time. He grabbed one, twisted the top back, and proceeded to shish-ka-bob the cricket, driving the point of the hook back under the prothorax shell, then around and back up the little butt. That keeps Jiminy kicking and squirming longer.

I watched as Donald opened the cricket box to expose the little side hole where only one or two can climb out at a time. He grabbed one, twisted the top back, and proceeded to shish-ka-bob the cricket, driving the point of the hook back under the prothorax shell, then around and back up the little butt. That keeps Jiminy kicking and squirming longer.

As the boys and I sat watching the maestro at work, I wondered how we would be able to cast in this mess of limbs, trunks and knees. I suspected that “flickin” would figure into the scheme, and I was anxious to find out.

“Okay, y’all watch this,” he told us. Donald held the bend of the hook in his right hand, between his thumb and forefinger, with the butt of the pole in his left. He looked at the trunk of a cypress maybe 10 feet in front of the boat and pointed the pole toward it.

He then slowly pulled the hook, line and cricket toward his cheek, the pole’s tip bending back, and released the missile.

The hooked cricket landed quietly just a few inches from the tree, floated for a few seconds, then slowly fell beneath the surface.

“Cool,” Dan said, wide-eyed. “Can I try?”

“Just a second,” his granddaddy whispered, staring at the gently rocking cork. He’d already noticed a little bump in the rhythm of the float.

“Come on, take it,” Donald whispered, his eyes now as wide as the boys’.

In a few seconds, the cork slowly slid along the surface, then disappeared into the shadows. Donald jerked the rod hard with both hands to set the hook. After a 10-second tug-of-war, Donald grabbed the line and lifted the fish into the boat. The fat shellcracker flipped and flopped on the deck, much to the boys’ enjoyment.

“Can we fwick some cwickets?” Sam asked, almost at the top of his lungs.

Daniel quickly admonished him for scaring all the fish away, as any big brother would do.

“You can flick a cricket here in just a second,” Donald answered, removing the hook and placing the beautiful bream on the stringer.

The art of cricket flickin’ is as easy as it sounds. A skill no doubt borne of necessity long years ago when the shellcrackers were on the beds deep in the cypress shallows.

Come give them a try. You can rent a skinny jonboat and motor, buy some crickets, pick out your cane pole and head for the cypress. You already know how to flick a cricket. Just make sure you hold the bend of the hook, not the point. And don’t launch it too close to your cheek.

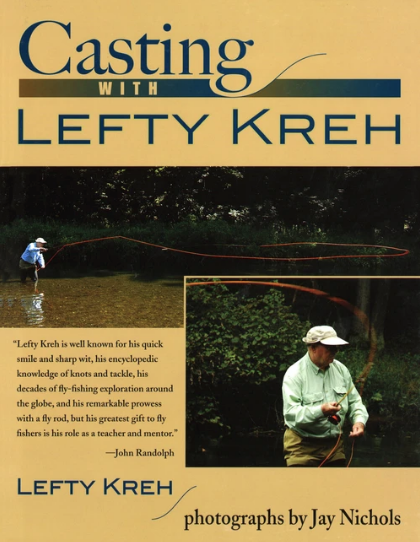

With over 40 casts covered in step-by-step detail in over 1,200 full-color photographs. Casting with Lefty Kreh is the perfect reference for the fly fisher who wants to improve his skills. Casting should be nearly effortless. Understand the physics and the dynamics of casting and how to adapt to various fishing conditions and your casting will greatly improve. That has been Lefty’s philosophy since he began teaching fly casting over fifty years ago.

With over 40 casts covered in step-by-step detail in over 1,200 full-color photographs. Casting with Lefty Kreh is the perfect reference for the fly fisher who wants to improve his skills. Casting should be nearly effortless. Understand the physics and the dynamics of casting and how to adapt to various fishing conditions and your casting will greatly improve. That has been Lefty’s philosophy since he began teaching fly casting over fifty years ago.

By fishing all over the United Sates and many parts of the world, Lefty learned the techniques experts use on different waters, in every situation imaginable. He shares that knowledge here through easy-to-understand instructions and full-color photographs the show exactly how to make every important cast. Buy Now