Looking back, it’s hard to remember just when we realized we might have a problem; probably when the creature opened its eye.

But there’s no question about when concern became panic, because that’s when it opened its horrible mouth and lunged at me.

I’ll never get over that mouth, with its row of flesh-tearing spikes dripping blood and the smell of rotted death when it roared. And another thing is for sure: If I had known the monster wasn’t dead, I’d never have to put my hand on its slime-caked hide — or put my foot in its mouth.

I’ll never get over that mouth, with its row of flesh-tearing spikes dripping blood and the smell of rotted death when it roared. And another thing is for sure: If I had known the monster wasn’t dead, I’d never have to put my hand on its slime-caked hide — or put my foot in its mouth.

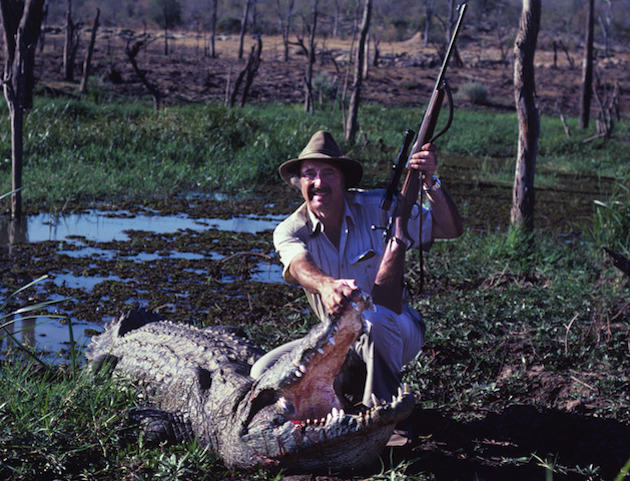

It was June of 1984, wintertime south of the equator, and I was on safari in Zimbabwe, the game-rich African nation once known as Rhodesia. My hunting pal was Jack Atcheson, the famed North American outfitter who books most of my hunts, and our Professional Hunter was the legendary Mike Rowbotham, now moved from Kenya to Zimbabwe and operating Hunter’s Tracks PVT, one of the country’s leading safari outfitters.

Our quest was bigger-than-average trophies, and during the preceding few weeks Atcheson and I had been hunting in South Africa where we’d bagged a half-dozen contenders for the Rowland Ward Record Book, including the shy, bush-dwelling nyala antelope.

Now we were after leopard, kudu and reedbuck, which tend to grow especially big in northern Zimbabwe. Already I’d killed a better than good Cape buffalo, which had been quartered and hung for leopard bait. It sometimes takes a few days for meat to get ripe enough to appeal to leopards, so we were passing the days looking for the odd trophy or cruising Lake Kariba’s shores, watching herds of elephant that came to drink and socialize.

The horror story had begun a week earlier when we headed our 16-foot fiberglass inboard/outboard runabout into the mouth of the Senkwi River and quietly cruised upstream. The Senkwi has another name, a long African name that I can neither spell nor pronounce, but when translated it tells a story of a fearsome god that dwells in a land where there is no sun and whose slobber is filled with such deadly creatures that everything it touches is killed and devoured. The legend goes on to explain how the god’s deadly drool gushes out of the earth and flows from a mountain, spreading death across the land, until it meets and is conquered by the benevolent god of the Zambezi.

The river of death no longer flows into the mighty Zambezi, but into Lake Kariba, but the putrid waters that spill into the man-made sea are still filled with the devil’s own creatures.

Beyond the first bend in the river of death, the world transforms itself from the present into the prehistoric. Trees do not bloom or bear leaves, having been raped by a blight that twisted them into pedestals for sulking vultures and carrion-eating water birds. Great shaggy nests of dead grass, as large as a native hut, sag from the gnarled tree limbs, and long-beaked birds cry out with cackling wails, lamenting the drabness of their plumage.

Little vegetation grew along the river; mostly the banks were bare earth and mud, dotted with shapeless stones and rimmed with a rock wall, all blending into a brown landscape. There was no game to be seen, but at one time or another wild animals had been there, for scattered along the shoreline we found skulls and other bones, as if a recent flood had cleansed the river’s depths of its dead.

Such a place demands silence, and little was said as we slowly cruised upstream. Oomo and Jason, the two black Africans who normally smiled and talked to each other continuously, were silent and watchful, clearly apprehensive but without knowing why — yet. Neither of them lived in the area and had not heard the legend of the river. Soon though, each would have his own story of the river to tell his grandchildren, and before the safari ended, both would tell me that they would never travel up the river again.

As we rounded each bend, there would be a splash a few hundred yards ahead and a quiet ripple would radiate from the shoreline.

“Crocs,” Rowbotham would say, his voice tight, “murderous bastards.”

I’d seen crocs before: in Sudan’s Nile swamps, in French Equatorial Africa and once in Botswana, where I’d witnessed an ear-shattering battle between a croc and a baboon. The baboon’s troop-mates had viciously attacked the crocodile, but the hard-scaled reptile never loosened its jaw-lock on the unfortunate primate. It simply slid beneath the water, and that was the end.

The crocodiles I’d seen before had never impressed me as being especially wild, but these crocs were so wary that there was little chance of getting a good look at one before it slid into the water and disappeared.

“Are they always this wild?” I asked Rowbotham.

“Are they always this wild?” I asked Rowbotham.

“Oh yes,” he answered, “they’re bloody spooky buggers … tough to get a shot at one. They’re more wary than any game animal.”

That did it; until then I’d never had any overwhelming desire to hunt crocodiles, but learning that they were hard to bag presented an irresistible challenge.

“Mike, I’ve got to get a croc,” I announced.

Rowbotham raised his eyebrow for a long moment, then gazed into the deathly green as if silently struggling with an unseen evil. Then the cloud passed from his face and he grinned with his characteristic good humor.

“Okay Jim, we’ll get one.”

Upstream a silent form stirred the water’s surface for an instant and then disappeared, radiating an arc of ripples across the slowly moving current.

The next day the weather turned cool and remained so for several days, spoiling our chances of finding a crocodile in a shootable position. More at home in the water than on land, they mainly come ashore to bask in the sun, but now with the sun hidden by clouds and the air cooler than normal, they cradled themselves in the warmth of the sluggish African water.

Several times that week we saw crocs in the water, as many as a dozen at a time, their snouts and eyes barely breaking the surface, looking like floating slabs of rotten wood. A few times I was only a few feet from the creatures, and a killing shot through the eye and into the brain would have been simple. But shooting a croc in the water is usually a waste because it will sink immediately — and who wants to go diving for a crocodile in their watery haunts?

Once while we were watching a group of crocs, an unsuspecting coot landed in their midst and swam toward one of the motionless snouts. What happened next is as difficult to describe as the speed with which darkness fills a room when the light is switched off. The coot was there, the water exploded and boiled for an instant, and then there was nothing but a gentle whirlpool to mark the transformation of life into death.

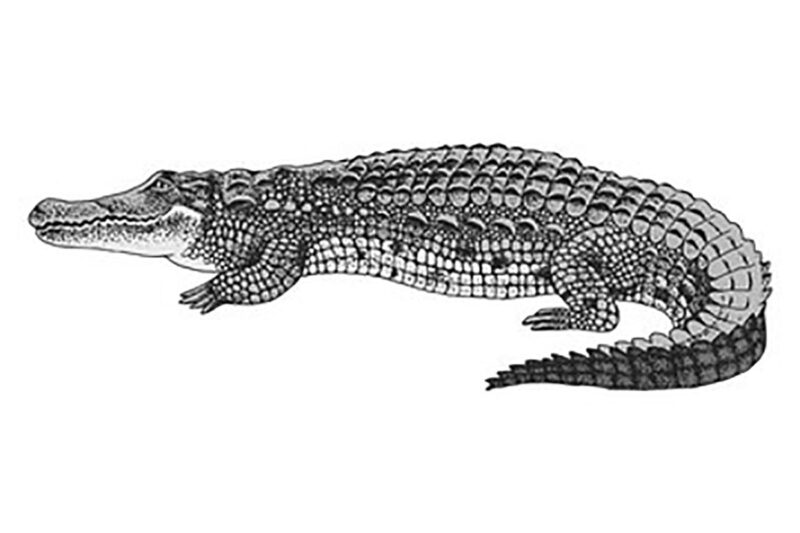

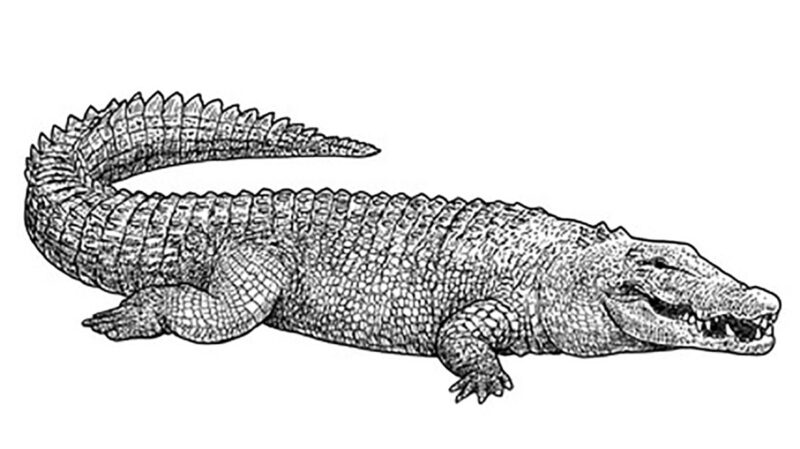

Despite their twin rows of sharp, interlocking teeth, each as long and as thick as a man’s thumb, crocodiles do not kill by biting or chewing their victims. The teeth are only a means of holding the victim while they kill it with quick, snapping rotations, breaking bones and ripping flesh before chunking the dead or near-dead creature down its gullet. They don’t chew their food and don’t need to, relying on powerful gastric juices to finish the meal.

A more efficient and remorseless killing machine does not exist in all of nature. So precisely honed are their killing equipment, techniques and instincts that millions of years have wrought no evolutionary improvements to Crocodilia. They are as they were at the dawn of creation, as patient, as watchful, as swift and as utterly incapable of remorse or pity.

A more efficient and remorseless killing machine does not exist in all of nature. So precisely honed are their killing equipment, techniques and instincts that millions of years have wrought no evolutionary improvements to Crocodilia. They are as they were at the dawn of creation, as patient, as watchful, as swift and as utterly incapable of remorse or pity.

By comparison, even such a killer of legend as the great white shark is a second-class performer. Both the crocodile and the great white kill without thinking, but the croc is infinitely more efficient because it thinks about killing, using practiced stealth to catch its victims. And it can do it on land as well as in the water, sprinting fast enough to grab even antelope.

The days following our trip up the Senkwi River remained cool and overcast, so there was little use in hunting crocs. Morning and evening we’d check our leopard baits, but our only trophy was a tremendous kudu bull Atcheson shot after a long and determined stalk.

After nearly a week of slow hunting, a dawn broke clear with the promise of a warm day. While checking a leopard bait hunt near the top of a rock ledge, we spotted a huge kudu bull on the thickly brushed plain below, and after a nerve-rasping game of hide and seek, I finally got a shot. It was my biggest kudu ever, putting not only myself but the whole camp in a festive mood.

By noon the unclouded sun had shoved the temperature into the 70s, making the day right for crocodile hunting.

“How about it, Mike,” I asked over lunch, “today’s my lucky day. Let’s go back up that weird river and try to bust one of those crocs.”

For a moment Mike considered the possibilities, serious-faced, the way he looked the day we were on the river. Then with a grin he shrugged off whatever was bothering him and said it was a great day to kill a croc.

Knowing from past experience that it was useless to try approaching a sunning crocodile by boat, we worked out a simple plan. Leaving Jason downstream with the boat, the rest of us would skirt the river on foot. By staying hidden behind the standing snags and logs that lay along the river’s bank, we hoped to stalk within shooting distance.

The plan worked perfectly. After a mile or so of skirting the river, we topped a low hill and found ourselves looking down on a marshy floodplain. At first the area seemed to be void of life, but after a quick look Mike crouched behind the rotted shell of a tree and motioned all of us to do likewise. Cautiously peering from behind a stump and surveying the area with binoculars, I spotted a sleeping croc, then another and another. Lying along the opposite bank there must have been a dozen or more. They were hard to see because their sun-dried hides blended perfectly with the black river mud. Their hides were not rich and glossy like a crocodile handbag, but dull and caked with mud and slimy moss. Hideously ugly yet possessing a hypnotic quality that made it difficult not to look at them. One can easily become transfixed by their evil majesty.

Some professional hunters become so obsessed by hunting crocodiles that they abandon their families, friends and businesses for months at a time. If a man must fight his inner demons, no symbol is more fitting than the crocodile.

Crawling to the stump where I was hiding, Mike whispered his assessment of the situation. “If we all try to get closer, one of the bloody bastards will spot us and spook the lot. Jack and I will stay here while you try to make your way close enough for a shot. Take your time and stay low. And remember, you’ve got to bust the bugger’s brain with the first shot or it will be in the water in a flash.”

The usual advice for bullet placement on a crocodile is “hit ’em behind the smile.” A croc’s mouth ends in a crook that does in fact tend to look like a cruel smile and is more or less on a vertical line with the eye. Somewhere along this line between the eye and the smile is what passes for a brain, a target not much bigger than a walnut. If you study a croc’s head, you’ll discover there isn’t even a place for a brain; indeed, the entire skull is designed for killing, not for thinking.

Hitting a big crocodile anywhere except the brain is pretty much a wasted effort. Unless you can blow one apart with a howitzer, their reaction to a body shot is almost no reaction at all. It takes death a long time to catch up with a reptile, so despite a crocodile’s considerable size, their only vulnerable spot is a tiny target that has to be hit just right or the trophy will be lost, to die later at the bottom of the water where it can never be found.

I had brought just one rifle, a custom-made .338 Winchester Magnum built on a ’98 Mauser action by the David Miller Company of Tucson, Arizona. This masterpiece has become my favorite big-game rifle because it never changes zero, the first shot is always dead on target.

I had brought just one rifle, a custom-made .338 Winchester Magnum built on a ’98 Mauser action by the David Miller Company of Tucson, Arizona. This masterpiece has become my favorite big-game rifle because it never changes zero, the first shot is always dead on target.

My handload was a 250-grain Nosler Partition bullet over 69 grains of 4350 and a CCI Magnum primer. This combination churns up about 2750 fps at the muzzle, more than enough horsepower to punch the Nosler all the way through a Cape buffalo, the way it had done earlier on the safari.

Crawling on the hard-baked earth, I zigzagged from stump to stump until I was within about 200 yards of the sleeping crocodiles. There I found a tree stump big enough to hide behind. Getting into a sitting position, I slipped the rifle’s sling behind my elbow and pulled it tight into a solid position. Then, by resting the rifle alongside the tree, the crosshairs jiggled as they settled on the nearest crocodile’s head.

Hold on … take your time and get a real trophy, I told myself.

Until then, I hadn’t given much thought to what a trophy crocodile should look like. The only difference I could see was size, so I resolved to shoot the biggest one. That turned out to be a simple choice, because the one that lay at the river’s edge with its tail still in the water was easily twice as big as any of the others. Luckily, the biggest croc was also the closest, lying broadside so that I had a clear view of its grim smile.

The crosshairs vibrated on the crocodile’s head for a moment, then for another instant they were still and the bullet crossed the river, crashing into the creature’s skull. Its tail violently lashed the water a time or two and then was dead still. The only motion I could see was a growing spot of thin red — behind the smile.

“Well done, Jim, that’s one more good croc,” Rowbotham was beside me, studying the beast through his dusty binoculars, making doubly sure it was dead.

“Oomo, run back and fetch Jason and the boat. Let’s see if we can get that bugger back to camp.”

A half-hour later, during which time the croc had not twitched, we crossed the river and I had my first close-up look at my trophy. It was absolutely incredible; no animal I’ve ever bagged or even seen was as awesome.

“My God,” exclaimed Rowbotham, “it’s one of the biggest crocs I’ve ever seen.”

That’s when I realized I hadn’t just shot a big croc, but a monster croc.

“This is unbelievable,” I said. “I think it’s the best trophy I’ve ever bagged, better even than an elephant with hundred-pound tusks.”

With Jack’s video camera recording the scene, I walked around the beast, pacing off its length, lifting and flexing its prehistoric feet, not believing, even with the evidence before me, that such a creature could exist, now or at any time. There was no bullet hole in the skull, only an inch-long crack where the .338 slug had busted its way toward the brain. Incredibly, there was no exit hole. The same load that could drill completely through a cape buffalo was stopped by the crocodile’s head.

“Open its mouth so I can get a shot of the teeth,” Jack requested, aiming his camera at the creature’s blunt snout.

“Open its mouth so I can get a shot of the teeth,” Jack requested, aiming his camera at the creature’s blunt snout.

Slipping my fingers between the teeth, I got a grip on the jagged upper jaw and heaved it wide. Teeth rimmed the mouth, like spikes of broken glass imbedded in the rim of a harem wall. The mouth’s lining was white and fleshy, like that of a snake, the whiteness spotted by watery reptile blood. The throat was chocked by a clotting puddle of blood, dripping from where its brain had been. Even in death the crocodile exuded an aura of evil, as if it still possessed a will to kill.

“Now that you’ve got the beast in hand, what do you plan to do with it?” Mike asked.

“I want it … every bit of it. I want the hide tanned with the head on. If I can’t get it in my house, I’ll leave it outside to scare away stray dogs and peddlers.”

“Well, the thing must weigh three-quarters of a ton. We’ll have to tow it back to camp.”

“Too risky, Mike. I don’t want to lose it,” I said. “We’ve got to figure out a way to get it in the boat, even if we have to skin it here.”

“I think we can get the whole thing in the boat,” advised Jack Atcheson. “I’ve been manhandling elk and moose for years and know a couple of tricks that might help us get the croc into the boat.”

With Jack directing, we cut stout poles; with two men to each pole, we levered the croc out of its slimy bed and — with considerable grunting and cussing in a variety of languages — heaved its head and forelegs over the bow. The massive head was too slippery to grip, so Mike rigged a rope bridle around the head and snout that offered a more secure handhold. As it turned out, this was about the only smart thing we did all afternoon.

When the crocodile was about halfway in the boat, we relaxed our grip for a moment to take a breather before the final heave. At that moment the massive body expanded as if it were taking a deep breath and the rear legs reached out with a jerky spasm of power. For a moment its feet ripped at the air, then the claws caught the edge of the boat and with incredible strength it pulled its mass into the boat, leaving only the six-foot tail dangling outside. Then it was still again.

I think I was the first to speak. “Reptiles will often do that. Their nervous systems doesn’t get the message that it is dead for hours after the fact.”

Jack and Mike agreed with my assessment of the situation, but the two Africans didn’t seem at all convinced.

“Well, anyway, it was nice of the bugger to help out, saved us a lot of sweat,” Mike said. “Let’s get the tail in somehow and shove off for camp.”

The crocodile’s 16-foot bulk almost completely filled the bow section, with its head jammed into the two-foot wide opening in the forward bulkhead. There wasn’t room to tuck the croc’s tail in the bow, so we secured it with a rope and pulled it more or less aboard. Then a new problem presented itself: The mass of weight in the bow was nearly dipping it underwater. A few more inches lower and the boat would sink!

This problem was corrected to some extent when the five of us climbed into the rear of the vessel, leveling it to some degree. Still, the boat floated nose down until we gained enough speed to lift the bow. Thus, with the craft more or less level, we cruised down the river of death into the vastness of Lake Kariba.

Even with the added weight slowing the boat, I figured we’d make it to camp before dark. Nothing to worry about now; there were plenty of camp workers to unload the crocodile, and after sundowners and a warm shower to wash away the stinking river slime, we’d have a hell of a time at dinner telling crocodile stories. There was no way I could know it then, but the crocodile story we would live to tell would be one of pure horror.

The first sign of serious trouble was a small but steady stream of water that rippled across the fiberglass deck from bow to stern. My guess was that the trickle was only water flowing out of the crocodile and would eventually stop. However, a few minutes later the trickle became a tide, causing me to go forward, crawling over the crocodile, to where the water was coming from. What I discovered was that both of the bow storage wells were flooded and overflowing, apparently by water washing under the gunwale cowling.

Jason was running the boat, and when I announced what was happening, his reaction was to slow the engine. Deprived of its planing lift, the bow dived beneath the waves and we would have sunk right there had it not been for Mike Rowbotham’s quick action.

Grabbing the throttle from the terrified Jason, he punched the engine to full power, causing the bow to lift just an inch or two above the lake’s surface. But even then we still had one hell of a problem. We were a half-mile from shore in a rapidly sinking boat. Could we make it? I didn’t think we could and began a mental inventory of the situation and our survival options.

The whole problem, of course, was the huge crocodile, but there was no possibility of getting it out of the boat in the time we had left, so even in death it was taking a terrible toll. The two Africans were in utter panic and probably couldn’t swim.

Are there life jackets aboard? I wondered.

Clearly, Jack would lose his expensive video equipment and the depths would also claim my David Miller rifle, worth at least $5,000. Mike’s double-barreled William Evans, worth more thousands, would go down too. But still, what bothered me most, more than the boat, the rifles, and the equipment, was losing the crocodile. I really wanted that damn crocodile.

I didn’t look at the shore, only at the waterline as it crept up over the gunwales and splashed inside, and at Mike’s hand on the throttle, urging the last ounce of speed from the overloaded engine. We couldn’t make it, I thought … but then I could see the bottom of the lake … five feet deep, three feet. We could make it! We made it! The boat crunched to a stop on the gravel shore, the engine still screaming.

A half-hour later, with the boat bailed dry, we nervously eased back into the lake’s main channel and resumed our course for camp. Not much was said about what had happened. We all knew how close we’d been to disaster, possibly even tragedy, and when you come that close, there isn’t much to say. I sat on the engine cowling, holding my rifle and studying the hideous design of the crocodile’s head.

And then its eye opened.

Considering the scare we’d just had, the idea of a live crocodile in the boat struck me as a hilarious possibility. The situation was made even more ridiculous by Jason’s proximity to the croc; no more than 10 inches separated the monster’s teeth from his bare feet and legs.

Considering the scare we’d just had, the idea of a live crocodile in the boat struck me as a hilarious possibility. The situation was made even more ridiculous by Jason’s proximity to the croc; no more than 10 inches separated the monster’s teeth from his bare feet and legs.

“Look Jason,” I said, pointing at the open eye, already laughing at what I anticipated the African’s reaction would be.

For a long moment Jason didn’t react at all; he just stood there regarding the red glowing orb with all the solemn detachment of a cow pondering a flower. Then the crocodile’s other eye opened …

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from Classic Carmichel—Stories From the Field available in the Sporting Classics’ Store.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form — until now.

Jim Carmichel hunted around the world during his 40 years as Shooting Editor of Outdoor Life magazine. But none of his amazing adventures ever made it into book form — until now.

Classic Carmichel features nearly 400 pages of hunting adventures and firearms expertise by Carmichel, widely acknowledged as one of the foremost experts on sporting arms.

Carmichel’s exploits and prowess had no equal during what is arguably the Golden Age of international hunting and shooting. These are not just stories by a well-traveled adventurer—they are pure literature, written with a style and eloquence that deserve inclusion in any collection of great outdoor books and writers. The big 9 x 10½-inch book will feature more than a hundred never-before-published photographs. Buy Now