Richie Nash had never seen a coyote on his family’s farm south of Monroe, North Carolina . . . but all that changed on a cool December morning as Nash sat in his comfortable box stand overlooking a freshly cut cornfield.

Half an hour after sunrise, Nash noticed a lone coyote streak across the field and dive into the adjacent woods before he could even raise his rifle. No more than ten minutes later four whitetail does and fawns emerged from the same copse of trees and began feeding on the corn. Another 10 minutes had passed when Nash spotted a coyote loping toward the deer, sending them scampering for cover. Nash leveled his .270 Winchester and dropped the coyote in its tracks.

Surprisingly, within minutes the deer returned and resumed feeding only a few yards from the dead coyote. Then, even more surprisingly, a second coyote came bounding toward the deer, sending them racing for the woods again. Nash’s rifle boomed once more and the second predator fell dead.

And then, to Nash’s utter astonishment, not only did the deer return to the field, but another coyote appeared, trotting right past his fallen comrades and scattering the herd. Nash fired for a third time, dropping it where it stood.

Altogether, this amazing sequence of events unfolded in less than 45 minutes.

The coyote played a prominent role in the mythology of North America’s ancient peoples. To them, he embodied craftiness, intellect and adaptability. The coyote was compared to the raven for his trickery. He was the subject of particular awe to Native Americans in the West, Southwest and Great Plains. That was his home long before the Navajo got there, or the Crow, or the Apache. His name was drawn from the Aztecs, who called him coyotl, or, “barking dog.”

The lack of interest and respect shown by early European settlers for the strange little “wolf” allowed the coyote to fly under the radar while real wolves were being shot or chased or poisoned out of existence. But the spread of strychnine-laced carcasses to kill wolves did have some effect on coyotes, as did the fur market. Each played a part in the coyote’s population decline, but never for long and never as drastically as other predators.

The modern coyote stands two feet at the shoulder and measures three to four feet from nose to tail. Weight varies wildly — from 20 to 50 pounds — depending on sex, region and subspecies.

The U.S. Forest Service recognizes 19 subspecies (16 in North America alone), the Mexican, northern and peninsula coyotes among them. Bergman’s Rule of biology explains these wide variations in size: The farther north a coyote is, the larger its trunk size (to better retain body heat) and vice versa for southern ‘yotes. Following the Similarly themed Allen’s Rule, northern coyotes have shorter appendages while southern coyotes have a lankier profile with comparatively longer legs and ears to help disseminate body heat.

The home range for a coyote can range from two to 25 miles, with the most fiercely defended territory between two and three miles. Seemingly always on the move, coyotes eat everything from rodents to bugs to plums to livestock to carrion — whatever comes close to their ever-open maws.

Daylight or dark doesn’t seem to make much difference to a coyote, though they are considered nocturnal. Yet as Richie Nash discovered, hunters can and occasionally do kill coyotes in the middle of the day. Still, the best chance for a shot come at night with, where legal, a spotlight.

The typical coyote pack is made up of a reproductive female and her pups, with bachelor males, non-reproductive females and sub-adults occasionally mixed in. The pack forms in midwinter, with mating season taking place between the start of February and the end of March. Gestation lasts two months and the average litter numbers six pups, which are born blind and nurse for a month. After that the mother begins chewing solid foods and regurgitating it into the pups’ mouths like a mother bird. The young leave their parents at six months of age.

Coyotes will make a den just about anywhere. They can dig their own but seem to prefer enlarging holes created by fallen trees, erosion or by other animals. After giving birth, the mother will continue to use the hole while her pups are at their most vulnerable — usually about a month. Coyotes also return to their dens periodically to rest, switching between several to prevent the buildup of fleas or the discovery of their hiding places. More often than not, however, they sleep in the open air.

Though coyote populations sometimes seem to be growing exponentially, Mother Nature does occasionally step in when their numbers grow too large. I remember a deer hunt in Kansas years ago when I watched a coyote stricken with mange fruitlessly try to catch mice in a field. Patches of bare, yellowish skin pockmarked the poor animal, which was obviously slowed by the deadly disease. No doubt it never survived the winter. The animals are also vulnerable to rabies and distemper.

Though coyote populations sometimes seem to be growing exponentially, Mother Nature does occasionally step in when their numbers grow too large. I remember a deer hunt in Kansas years ago when I watched a coyote stricken with mange fruitlessly try to catch mice in a field. Patches of bare, yellowish skin pockmarked the poor animal, which was obviously slowed by the deadly disease. No doubt it never survived the winter. The animals are also vulnerable to rabies and distemper.

Coyotes are the most vocal of all wild canines, having at least 11 different yips, howls and barks for communicating with family members and other packs. Researchers believe howling is a long-range conveyor of messages, while barks are used for location and to request information rather than deliver it. Barking is also used to signal warnings to other coyotes. The two can be combined between mated and territorial pairs, with the male howling and the female yipping, barking and making short howls of her own. Mother coyotes are particularly talkative when it comes to their pups. Calls can indicate danger, dinner or other, more complex messages.

Some researchers believe coyotes even have a unique “voice” all their own, as distinguishable to other coyotes as the different voices of a human family. Duration, tone and the rise and fall in pitch all play a part. Distance doesn’t seem to matter. Researchers think coyotes can tell which song dog is calling from as far as three miles away.

The coyote is certainly one of the smartest wild animals, especially when it’s trying to avoid danger. I remember back in my teenage years in South Dakota when the men in our church would organize jackrabbit drives. Rabbit pelts brought a buck apiece at the local tannery back then and we’d give the proceeds to the poor and needy. Forty or 50 of us, all carrying shotguns, would surround an entire section of farmland and slowly walk toward the middle. There was no escape for the jackrabbits, and we’d kill dozens in a single drive. Coyotes were also plentiful at the time, but I can’t remember ever seeing one taken. The moment we’d start walking, they’d slip out through gaps between the shooters or duck into burrows dug by badgers.

Long regarded as shy and secretive, the coyote of today is a different breed. Not only is it more prone to living and hunting in close proximity to man, in some cases its behavior has become outright brazen. A recent case in point was a coyote that ventured into the Myrtle Beach International Airport in South Carolina. The animal was finally cornered in a TSA checkpoint where it was captured and later euthanized.

Reports of even more daring and aggressive coyotes are numerous, particularly in the eastern half of the country where the predators are slipping into suburban back yards and making off with house cats and small dogs. Urban areas are seeing coyotes as well. A single coyote was caught in New York City in 1999; there are now dozens of confirmed coyotes within city limits, including a pack that made Central Park its territory. Ditto for Chicago and Los Angeles, which have both seen the canids move into town.

Researchers have even found that coyotes will look both ways before crossing a road, something their equally prevalent neighbor, the white-tailed deer, has not been able to accomplish. Like beauty, the difference is in the eye of the beholder: A coyote’s binocular vision allows it to reconcile an object’s growing larger with its growing closer. Conversely, deer do not understand that a headlight’s beam growing larger means the car is approaching. This difference has allowed coyotes to survive even better than the ubiquitous whitetail.

Hybridization has been a key factor in the coyote’s recent surge in numbers and range. The shy dogs of the western plains began breeding with timber wolves at some point in the 20th century, with their progeny showing a larger build and bite. Researchers believe that many of the “coyotes” hunters have seen and shot over the last few decades are actually varying shapes and sizes of the “coywolf.”

Dr. Roland Keys of North Carolina State University put the typical coywolf at 55 pounds, with longer legs and jaws than a coyote and an overall heavier musculature. Recent DNA analyses of 437 coywolves in the northeastern U.S. and parts of Ontario found the typical mix to be roughly 65 percent coyote, 25 percent wolf and 10 percent dog.

Organizations like the Quality Deer Management Association and the National Wild Turkey Federation have long analyzed the relationships between fawn/poult mortality and coyote predation. Many deer hunters have speculated that coyotes could even be killing adult deer, but researchers were skeptical of the possibility. A single coyote has no problem killing a fawn; a pack may even succeed in bringing down a weak or old deer. But a single coyote could not take on a healthy buck or doe in its prime and wrestle it to the ground.

But for the coywolves, deer are easy pickings. One account from early 2015, albeit a disputed one by Michigan’s DNR, had an unknown number of “big coyotes” injuring a full-grown horse so badly that it had to be put down on the spot-all while its owner heard coyotes howling in the nearby trees.

Like the much larger gray wolf, red wolves have also interbred with coyotes. Labeled in 1980 by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as extinct in the wild, red wolves have been the focus of several reintroduction projects. One of the most notable of these efforts was the introduction of captive-bred red wolves into North Carolina’s Alligator National Wildlife Refuge in 1987. Four pairs were released into the coastal peninsula above Lake Mattamuskeet. Hunting there was strictly prohibited for fear the animals would be mistaken for coyotes and shot. In reality, the wolves weren’t mistaken for coyotes but were taken for mates by coyotes. The first hybrids were noted in 1993, with many questioning if there is even a truly purebred red wolf left on the peninsula. USFWS has deemed interbreeding with coyotes as the greatest threat to the 50 to 75 red wolves in the area.

What makes the coywolf so intriguing and vague is its ability to breed with wolves, dogs or other coyotes to produce fertile pups. To be considered a unique species, a coywolf’s offspring would have to be sterile unless both parents were coywolves.

In either its original or hybridized form, the coyote has established itself as arguably the most successful predator in North America. Despite man’s attempts to reintroduce wolves, cultivate bear populations and generally foster the return of large predators to wild ecosystems, the coyote has become firmly entrenched in the North American landscape. With their clever ways of adapting to the ever-changing environments around them, their position at the top of many food chains isn’t likely to change in the foreseeable future.

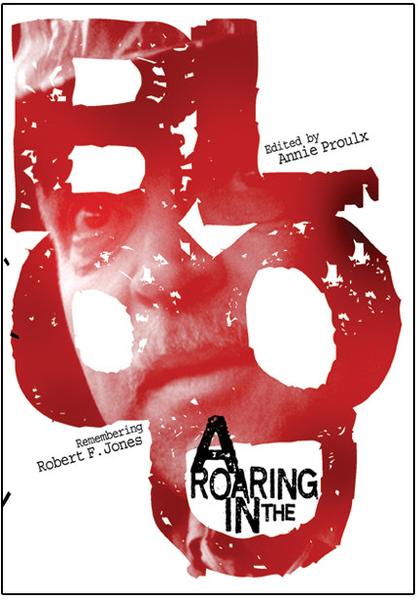

Hard-hitting staff writer for Time and Sports Illustrated; critically acclaimed author of such novels as the cult classic Blood Sport and the Western epic Tie My Bones To Her Back; essayist, adventurer and sportsman of truly Hemingwayesque proportions . . . Robert F. Jones was all these things and many more.

Hard-hitting staff writer for Time and Sports Illustrated; critically acclaimed author of such novels as the cult classic Blood Sport and the Western epic Tie My Bones To Her Back; essayist, adventurer and sportsman of truly Hemingwayesque proportions . . . Robert F. Jones was all these things and many more.

Three years in the making, A Roaring in the Blood: Remembering Robert F. Jones paints a frank, funny, richly textured portrait of this lion of American letters, as seen through the eyes of his friends and as revealed through his own hard-muscled prose. Buy Now