That year Tony’s mother forgot all about Christmas. None of us was surprised, and nobody blamed her. She had many other things on her mind.

Tony and I lived a few houses apart on Long Lake and for years had spent many of our spare hours together, exploring the lakes and woods near home. We knew each other like brothers. He was 14 that winter, skinny and so tall he was in the habit already of stooping at doorways. His father had died in August after a long illness, and Tony had decided he was responsible for two little brothers who had to be kept away from matches and knives, and for a 13-year-old sister who was nearly as tall as Tony and possessed not a trace of respect for his authority.

Tony had decided also that it was his duty to cheer his mother for the holidays and that a dinner of baked grouse and pike fillets would distract her from her troubles. I came from a turkey and ham family myself, and was a stickler for tradition, but I went along with Tony’s plan because he was my friend.

In those days, we sometimes hunted grouse with my dog, Lady, a fat-as-a-sausage beagle who in her prime had been known to climb trees after squirrels and was the only beagle I have ever heard of that would point birds. She had grown up with a pair of my father’s Brittany spaniels and had learned to lock into a rigid, trembling, belly-to-the-ground point whenever she scented a gamebird. You could trust Lady’s points, but she was easily distracted by rabbits, squirrels and deer. You also had to watch her around raccoons, porcupines and skunks.

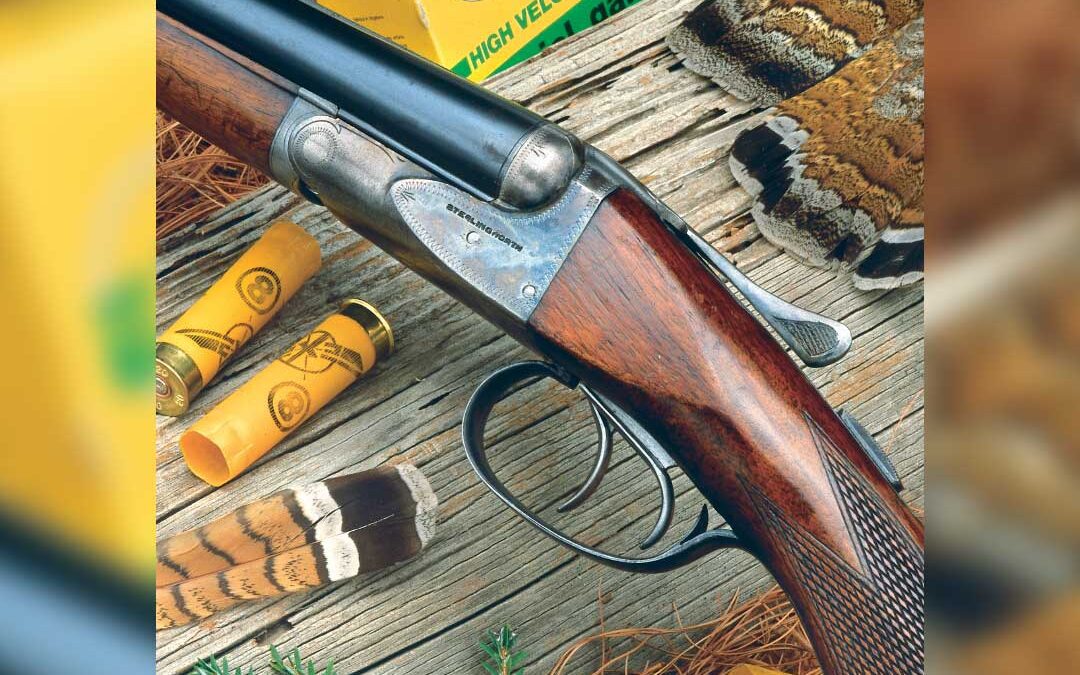

Tony and I had one gun between us, an ancient Fox Sterlingworth that kicked like a howitzer and had been presented to me with formal solemnity on my 12th birthday. It had been my father’s first gun, presented to him by my grandfather, and it was understood that I would eventually pass it on to my own son or daughter. It was my most treasured possession, a man’s gun, and I was more proud of it than anything I owned. The day after I received it, my father had taken me to his duck blind at the Mud Lake Flooding, where I promptly dropped a drake mallard that rocketed past at 60 yards. It was the only bird I ever got with that double-gun.

Over the years, Tony and I shot at a lot of grouse with my shotgun, but we never killed one. They were too fast and evasive for us. We would watch them thunder away, not a feather ruffled, and shake our heads and laugh. If it had been Tony’s turn to shoot, he would hold the gun up and admire it.

“This is a sweet shotgun,” he would say. I agreed. “You take good care of this baby,” he said. I would, I promised. But more often than not it was he, not I, who cleaned it at the end of a day of hunting.

Our effort to shoot a grouse for Christmas nearly failed because the snow was so deep that poor Lady could not keep up with us. She was forced to practically tunnel through the woods and kept going off in random directions, whining in frustration and snorting up little spouts of snow. She finally flushed a grouse from some dense hemlocks, but it flew off on the far side of the trees. All we could see of it was the trail of sifting snowfall as it passed through a stand of evergreens.

We hunted three or four days without seeing another bird until, unexpectedly, with Lady miles away, we almost stepped on one that was roosting in the snow. It blew up from theloose fluff, throwing snow like we’d stepped on a land mine. If I had been carrying the gun, I would have been too startled to even think of wasting a shell. But Tony swung on the bird and fired, tumbling it into the snow. We could not have been more surprised. We dressed it and took it home to store in my parents’ freezer.

Now that we had a grouse in hand, Tony was determined to get some pike fillets to go along with it.

He had already decided the only way to get a northern pike large enough to feed his entire family was to spear it.

I had little hope for success. Long Lake’s pike population had continued to decline, and the few survivors were battle-wizened and cautious. Besides, neither Tony nor I had any experience throwing spears at fish. It was a legal and time-honored practice, but my father frowned on it, proclaiming it underhanded and archaic, a sanctioned form of cheating that had spoiled fishing in Long Lake.

Tony’s father had at one time been enthused enough to build a shanty and equip it with a stove and spear, but an ice shanty requires almost daily maintenance. If you did not frequently jack up the corners and support them with blocks of wood, the entire structure would gradually sink into the ice until the only way to get it off the lake was to chainsaw the freestanding portion, leaving the floor behind.

Tony’s father had been a long-distance trucker, seldom home long enough to give proper attention to the shanty. Eventually, he had pulled it to shore and left it there, perched on cement blocks beneath the birches.

The day before Christmas, Tony and I spent the morning digging the shanty out of the snow and dragging it with his toboggan onto the lake. So much snow had fallen that the ice was sinking, forcing water to the surface and forming slush. We spudded a three-by-three-foot hole in the ice and horsed the shanty into position over it. Once it was in place and the hole scooped clear, we banked up snow around the shanty to keep light from seeping inside. We ignited the stove. When we closed the door we were enveloped in darkness.

As our eyes adjusted, we looked down the hole into an unexpected world. Lit green like an aquarium, quiet as the inside of the earth, it was a world you wouldn’t know even existed if all you saw of a lake in winter was the featureless snow that covered it. On the bottom, ten feet down, rested wisps of pikeweed and skeletal maple leaves. Outside, the lake’s surface was solid white and frozen to stillness. Down below was color and movement and life.

Tony picked up his father’s spear and removed the block of wood that protected its six sharp tines. The five-foot shaft was weighted at the bottom with two pounds of lead. An eyelet at the other end was attached to a coil of cord.

We used a wooden decoy weighted with a lead core and shaped like an eight-inch, red-and-white sucker. Tony tied it to a spool of braided line and lowered it into the water. He jigged it and it swam in circles, rising and falling like a merry-go-round horse. If he stopped jigging, the decoy rested dead and wooden in the water. If he jerked it, it soared like a startled bird.

The interior of the shanty warmed and we took off our jackets. I turned to hang mine on the wall and bumped the spear, knocking it hurtling in a stream of bubbles to the bottom. When the water cleared the spear rested at an odd angle in the muck.

Tony pulled it to the surface, bringing up a trail of leaf parts and mud. Then he sent the spear into the water again—not throwing it so much as pushing it off, letting the weight do the work. It shot straight down and stuck in th e bottom. I took a turn, aiming at a length of weed I could imagine was a fish. Tony balanced the spear again on the edge of the hole and we settled down to wait.

Sitting there in the warm, dark shanty, I started thinking about Christmas. Like Tony, I was 14 that year and, though I no longer approached the holiday with the same expectations I had as a child, I was reluctant to give them up.

For months, I’d been dropping hints to my parents about a gasoline-powered model airplane. I knew it was not a sensible gift because it required an isolated strip of concrete or asphalt for take-offs and landings, and there was no such place for ten miles in any direction of our house. But I was child enough still to want a child’s toy. I wanted the old excitement.

“Tony,” I said, “what do you want for Christmas?”

He turned slowly, his mind elsewhere. His face was lit from below with eerie light. “I don’t know,” he said. “Nothing much.”

“Nothing much? Come on.”

“Some school clothes. Maybe a hunting knife.”

I said nothing about the airplane.

I took a long turn with the decoy. After awhile, my arm moved independently of me. The decoy below vaulted and sailed, and seemed to have no connection to my arm. I started getting restless. I wondered why Tony was not content to just eat store-bought turkey like everyone else.

I handed the decoy line back to him and stood to put on my coat. “I’m going for a walk,” I said.

The sun was low on the hilltops, the day fading down to pale blue and the cold night air descending. A few other shanties were scattered across our end of the lake, but they sat unused and frozen-looking.

I imagined my parents at home, preparing for our traditional Christmas celebration. I thought of Tony’s mother, then of his father. I hadpreferred death when it was an abstract concept. That summer it had struck too close to home and I did not know what to think. Tony and I never talked about it, not once. I convinced myself he preferred it that way.

Then Tony shouted. I spun and looked at the shanty. There was a clatter inside and the shanty seemed to rock and tremble, like a cartoon rocket about to launch. The door burst open and Tony tumbled out, his spear at waist level impaled through a gyrating northern pike. He could hardly hold it up.

Ten pounds, I thought in disbelief. Fifteen pounds.

Tony threw it down on the ice and danced in triumph around it.

It was not 15 pounds. More like 10. Eight, to be honest. But it was large enough for Christmas dinner.

Tony’s grin was so broad I thought his face would cramp. He told me what had happened, how the fish had appeared suddenly, without warning. One moment there was nothing, the next there was a northern pike, the largest he’d ever seen, hovering in the center of the hole. It had focused intently on the decoy, its fins waving to keep it in position. Tony had pushed the spear off firmly, the way we had practiced.

We walked across the snow and ice to shore, where Tony waited while I ran up the hill and took the wrapped grouse from my parents’ freezer. Then we walked together to his house, like wise men bearing gifts.

His mother sat alone in the kitchen, dressed in a sweatshirt and jeans, her hair pulled back and pinned so tight it stretched the skin taut on her face. The house was dark, the table empty. No food cooked merrily on the stove.

I realized for the first time what Tony had been so determined to do, and it made me ashamed for not taking his efforts more seriously. I was ashamed, too, because my family was so stable and complete, our Christmas so abundant that the bounty overflowed outdoors. There were wreaths on our doors and an electric Santa on the roof and a two-string coil of blinking blue lights around the spruce beside the driveway. Inside were Christmas music, a crackling fire, dishes heaped with nuts and the chocolate candies my mother made every year. Our Christmas tree was large and full, lit as bright as the night sky, with an enormous silver star on top.

I was ashamed and grateful and guilty, all at once.

Tony and his sister had set up a tree, but it was skinny and sparse, with a few tinny ornaments and a scattering of tinsel. I realized then, with the kind of sudden, irrefutable insight kids are prone to, that Tony’s family could not stay here much longer, that the house would be sold, that this would be the last Christmas we would spend as neighbors.

It took her a few moments to notice us, but when she saw what we were offering she smiled. She motioned for us to put the fish and grouse in the sink, then pulled Tony into her arms in a hug. His sister and brothers appeared. Everyone was smiling. That evening they would have the goofiest Christmas meal of their lives and it would be a turning point they would always remember—not the first Christmas without their father, but the Christmas Tony brought home pike and grouse for dinner.

It was nearly dark when I headed home, following the deep trail Tony and I kept open all winter between our houses, and walked in on my mother’s usual Christmas Eve feast. My grandparents were there, and uncles and aunts, and all my cousins. There was venison, sliced thin and served with gravy, as a side course to the turkey. We had mashed potatoes, stuffing, sweet potatoes with melted marshmallows, cranberry sauce, two or three kinds of pie and ice cream.

I watched my father as if I had never seen him: A big man at the head of the table, his sleeves rolled up, laughing at someone’s joke while he used a carving knife and fork to slice the turkey into thick white slabs. I was never so grateful to have himhome.

In the morning we opened presents and to my surprise I was handed, not a gasoline-powered airplane, but a mysterious, long, heavy package. I tore into it with fear and disbelief. Inside was a new pump-action 20-gauge shotgun. It was the exact gun I had been coveting in catalogs for years. I had always been so sure it was beyond any possibility of possession that I had never dared mention it to my father.

I was stunned. My parents sat close together, their eyes bright, watching my reaction. I could not believe they would buy me such a gift. Their generosity humbled me. I wanted to emulate it.

After breakfast, I cleaned and oiled the old double-barrel and replaced it inside its leather case. I wrapped it in Christmas paper.

My father watched. “What about shells?” he asked. He helped wrap two boxes. They made heavy, satisfying packages in my jacket pockets.

Outside it was cold, the morning air harsh, the snow crunching underfoot like Styrofoam. Tony came to his door wearing a new sweater over his pajamas. Behind him his brothers stood five feet from one another, screaming into a pair of walkie-talkies. Tony grinned at the commotion and stepped aside to invite me in, but I stood my ground, hands behind my back, breath hanging in the cold air.

I’ll never forget his eyes, the way they grew wider and wider as I held the bright package out to him.

Note: Excerpted from A Place on the Water: An Angler’s Reflections on Home by Jerry Dennis. St. Martin’s Press, 1993.