Whimsical and capricious in all its movements, the woodcock continues a source of surprise to the oldest gunner, until he learns to be surprised at nothing it does.

The day had begun with a drizzle that looked as though it had set in for a long spell. In such weather there’s not much work outside the farm buildings, so after the chores were done the man had taken his old Belgian gun, filled his pockets with shells loaded with the blackest of black powder and gone hunting. Now he was back, emptying the contents of his smelly pockets on the kitchen table.

“Them’s teal ducks and this here one is a mallard duck,” said the hired man who had just come in with his old setter. “An’ this,” taking out a small brown bird, badly rumpled and oddly shaped, “now, I’ll bet you can’t guess what this is! Well, sir, this here is a timberdoodle, an’ it’s the first one I seen this spring.

“What’s a timberdoodle? Well, near’s I can make out, it’s a kind of a snipe-bird that lives in the woods mostly an’ only comes out by nights. Some calls ’em night pa’tridges and some says they’re blind snipes, but I think timberdoodle about fits ’em, fer they live in the timber, and it certainly doodles a feller to know what they’re a-goin’ to do next.”

The bird was a woodcock and it must have been one of the first to wander back to the scene of its childhood.

“He was amongst them little willers above the mill,” said the hired man, “an’ when the dog here stood on ’im, I thought mebbe it was a song sparer or somethin’, fer he sometimes pints them pesky things when they ain’t much else around. But it wa’n’t, it was a timberdoodle, all right, and here he is. Yes, I’ve shot lots of ’em an’ they’re pretty good eatin’. “Tain’t hardly right to shoot ’em in the spring, seems kinder like eatin’ your seed pertaters, and I wouldn’t have shot this one, but he took me so by s’prise I done it b’fore I thought.

Hunt created this artful painting in 1906. It depicts a pair of woodcock in their courtship flight.

“That’s the way you have to shoot them birds anyway, an’ I guess I got the habit pretty bad now. They lay aroun’ here and I found a nest in the huckleberry swamp last summer. ’Long in August, when the work gets slack, I’ll take you out with me an’ the ol’ dog here, an’ we’ll have some fun with these timberdoodles, or woodcocks—as you call ’em.”

When August came we went woodcock shooting many times, in certainty of plenty of birds, serenely unconscious of any harm done to the younger generation of gun-lovers.

Down the lane and through the pasture we used to go, then across the clover field where the second growth was blossoming.

The bees droned through the hot summer sunshine. The air palpitating with heat mirage, danced and waved over the fields of corn and stubble, turning up the leaves of the solitary oaks until the pale undersides of them looked whitened with the dust.

Downhill through the sunlit spaces and wide shadows of the big woods our course led to softer ground, where pungent odors of dogwood, wild rose, and sassafras filled the air. Blackberry, cat briars, and tangled wild grapevines here grew to tropic size and sullenly ensnared us. Creepers scratched our sweaty hands and cobwebs streamed stickily across our heated faces. Rank, swollen-looking vegetables covered the soft black loam, clumps of heavy ferns grew among the bogs and tussocks, and over all stood the stream-following thicket of alders, thorns, and wild plum trees.

The warm moist air of this sunlit tangle is charged with the scent of game, and presently the lashing tail and short careful quarterings of sober old Joe end in a frowning, drooling point. Our heartbeats go up about five points in the delicious certainty that a woodcock is very, very near. We step forward to see more clearly where he must flush, and up he darts not three feet from the old dog’s nose, hangs for a moment before the screen of fox grapevines and darts away through some airy passage in the leaves.

In that brief glimpse our excited eyes have photographed the details of his feathers, the light of his eye, and even the pinkness of the long toes that he trails behind. The sound of the whistling and flitting of wings through the tangle are poor guides to good shooting, but a hunter with the love of the game in his heart will shoot quick and straight, instinctively putting the charge of shot right into the line of flight as the woodcock crosses.

Now is the joy of woodcock shooting when you feel in your soul that you have made a good shot, but with room for a glow of satisfaction if sober old Joe brings a cock in response to your “dead bird.” It is a great moment when this beautiful gamebird comes to hand from the tender muzzle of the dog.

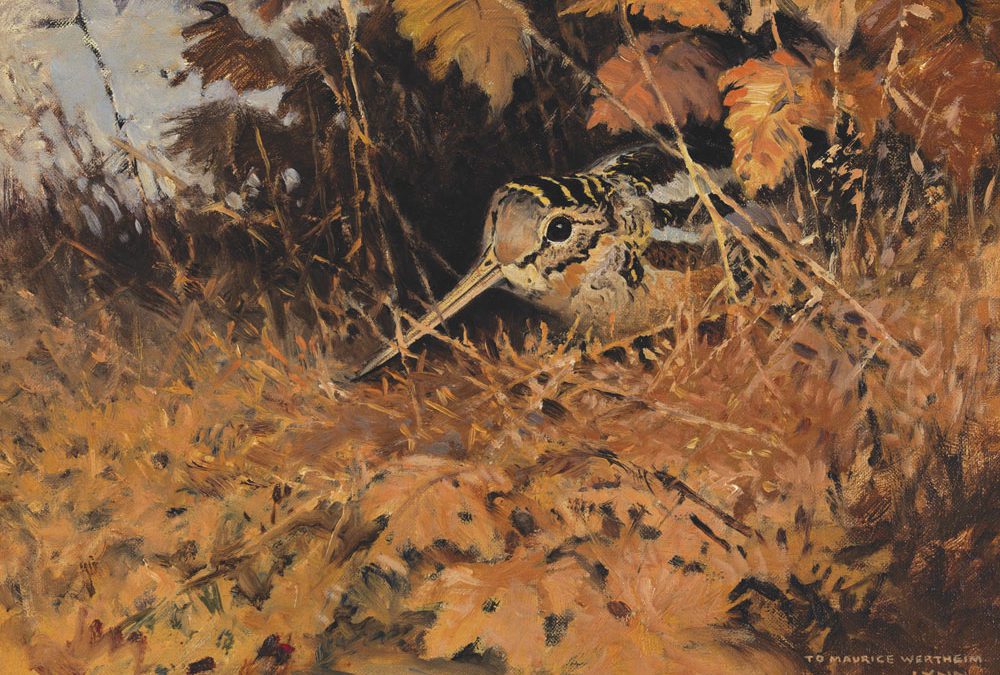

What a big, odd-shaped head, and how rich and gamey are the colors of the fluffed-out feathers! All woodsy grays and browns, so subtly suggestive of the shy life he leads beneath the ferns and mandrakes of lowland forests. His abnormally large eyes are set at the top and back of the head, so he can see much better above and behind than forward and down, which is a good arrangement, for he gets his food by thrusting that long, sensitive bill into the loam where grubs and worms abound, and so can use his eyes constantly for lookout duty.

He has the distinction, too, of possessing ears located directly beneath his eyes instead of behind them as in most birds, and ornithologists say that his brain is strangely tilted up so that its anatomical base looks forward, but this seems in no way to have interfered with his wits, for he is a knowing bird, as any cock shooter will testify.

The ages of natural selection that have adapted the woodcock to its habitat have done even better by its nest and eggs, or rather by its eggs, for the nest is always an apology scraped in the mould beneath the ferns, and so, hardly distinguishable from the ground. But it is a remarkable fact that the eggs themselves, whether the spots are few and large or numerous and small, usually conform in general tone to the ground upon which they are laid. And a woodcock’s nest is a rare, rare find. Like the hummingbird’s nest, it appears only when thoughts of it are farthest from the mind.

The female bird is larger than her mate, and very likely after the wooing is over becomes boss of the house, as is often the case with species wherein a similar advantage exists in favor of the so-called weaker sex. Their courtship is freakish to a degree, but, because of the wily shyness of these birds, is very seldom witnessed.

A lowland pasture near poplar swales and wet woodlands is most likely to be the scene of their lovemaking. If you can lie still on the damp ground through the chill of an early spring twilight, you may be rewarded by seeing the male, uttering a sharp scraping note, flit out into the damp obscurity, like a big bat, weaving about in rising circles until he has described a spiral, at the top of which he often swings widely about, and, finishing with a whistle, drops straight down to where the admiring female awaits him.

Woodcock choose nesting sites with the same disregard for conventions that mark their other habits, and the domestic operations, though usually begun in April in our latitude, are sometimes as early as March, and again may be delayed to July. The late nests are probably the result of misfortune with earlier broods.

Baby woodcock are the dearest little youngsters one can imagine. They leave the shell ready clothed in a soft yellow down mottled with seal brown, and with legs, feet, and bills much too large for their convenience, particularly the bills, of which they seem to be ashamed, for their sole thought in attempting to hide appears to be to thrust them under bits of grass or leaves.

Unlike quail or grouse chicks, the young woodcock are feeble, tottery little fellows, greatly handicapped by that ungainly bill and continually stepping on their own toes. The helplessness of the babies, however, is more than offset by the watchful devotion of the mother, who will almost invariably remove them to a safer place when they have been disturbed. The mother bestrides a chick and, with her legs pressing it firmly against her body, flits lightly away through the alders with her treasure, returning for each youngster until they have all been safely stowed away in some mossy nook in the tangle of the swamp.

Shooting begins in many states on the first of July, and from that to the return of the few survivors in the spring they are bombarded and pounded at in every state east of the 97th meridian.

When the hills and distant woods are empurpled by the smoky autumn sunshine, the maples are orange and gold, the sumacs lurid red and the air like wine, this listless summer bird becomes an animated firework that pitches away in a dodging, turning, twisting flight, with a speed calculated to try the mettle of the quickest shot.

Ah! How we love to dwell on those choice pictures of the statuesque dogs trembling in beautiful outline against the frosted green and gold, with the heavy scent of woodcock breathing through their nostrils. In these crisp autumn days the cock for the most part lies well to the dogs, and his foraging expeditions among leaves and moss and loam leave an excellent trail. He does not try the dogs by running, as does the grouse sometimes, and pheasants and rail nearly always, so that wild flushes and broken points infrequently disturb you.

You step forward to flush and up he goes with a whistling rush on a 45-degree line for the treetops. Its line of flight is hard enough in itself to follow with a gun, but when this is aggravated by rockety turns and twists, the woodcock becomes a problem that only clever snapshooting will solve. And it is best to stop him here if you can. This October bird will not pitch carelessly back into cover before he is fairly out of reach, for he can clip along like that for half-a-mile before he stops at some inviting swale.

Woodcock by no means confine themselves to lowland thickets. Among the grub oaks and maple saplings of a recently cleared southern slope he may be found exploring beneath the fallen leaves in rich black earth for crawly things he likes to eat.

Low, heavy woods with little underbrush will often shelter him after frost has stiffened the ground of his favorite swales. Nor is the possible cover yet exhausted, as you will find if you walk through the hollow of that cornfield where the stalks are such giants and the ground is rich and moist. His borings will tell you he has been there, and if the day is dark or evening is drawing near, the chances are that a cock or two have pitched upon this promising place, and their bat-like forms will flit out before you into the gloom with an eerie whistling of wings.

Coming home from a day of indifferent fortune at finding grouse in the glens of the hills, our party of three was obliged to cross a sluggish, winding brook running through a flat. There was no bridge and the water was too deep for wading. The discomfort of rain and growing darkness was now aggravated by a northerly wind that promised cold weather in a few hours.

After some distance walking upon the bank, we found a woven wire fence that crossed the stream through an alder thicket. Utilizing this as a bridge, we were soon across only to discover one of the dogs, an old pointer named Bess, was not with us. She would respond neither to calls nor to commands, so handing my gun to a companion and with wrath in my heart I crawled back across the fence to get her. There on the other edge of the thicket I found old Bess drawn up as stiff as glass, rolling her eyes around to me as cautiously as if she feared that movement would break the scent.

“Your silly old dog is standing a rabbit!” I shouted down the now roaring wind, but at the sound of my voice there arose the shrill, thrilly whistle of a woodcock’s wings, and I saw him darkly against the faint light of the west, whipping like a flash through the tops of the saplings.

“Oh, woodcock, woodcock!” I yelled and, at the sharp report of one of the guns on the other side, two more cock swished out into the dying light, climbing high in the air and tearing downwind as only a woodcock can go. I saw one of them go limp as a rag and fall without so much as turning over, and then the other with a shot in the head came whirling down like one of those toys made of feathers and a cork.

The old dog moved down the bank of the stream to where the brush was taller and many of the saplings wore their tattered rags of clothes. Presently she stood again, and before I could shout a warning, the shrilling of wings was followed by a shot and then another; then three so close together they were scarcely to be distinguished.

Eight woodcock had left the 20-yard strip of brush, and in that wretched light six of them had fallen to the gunners across the stream.

Whimsical and capricious in all its movements, the woodcock continues a source of surprise to the oldest gunner, until he learns to be surprised at nothing it does.

But he is the gamebird for all his oddities, say what you will of quail, grouse, or ducks, and I suspect that many devotees to these birds cherish a secret tenderness for the little brown prince of the ferny brakes and poplar swales. And if the treasure corners of the truest sportsmen’s memories could be explored, I think the choicest picture in every one would be of a rocketing woodcock among the sunlit treetops against the autumn blue, pitching limply over, cut cleanly and surely down.

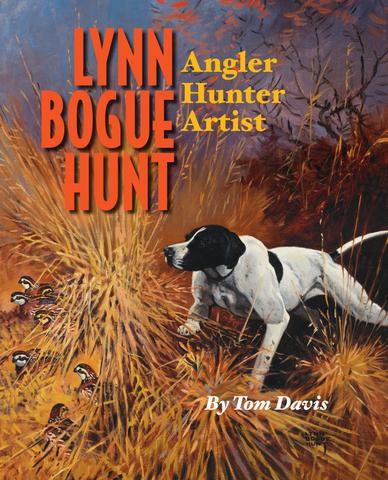

Angler, hunter and artist, Lynn Bogue Hunt was America’s most popular and prolific outdoor illustrator of the mid-20th century—the “Golden Age” of the American outdoors. He painted a record 106 covers for Field & Stream; illustrated dozens of books on waterfowling, upland bird hunting, and saltwater fishing; designed the 1939-’40 Federal Duck Stamp; and was described by his friend Ernest Hemingway as “the finest painter of game birds that we have in America.”

Angler, hunter and artist, Lynn Bogue Hunt was America’s most popular and prolific outdoor illustrator of the mid-20th century—the “Golden Age” of the American outdoors. He painted a record 106 covers for Field & Stream; illustrated dozens of books on waterfowling, upland bird hunting, and saltwater fishing; designed the 1939-’40 Federal Duck Stamp; and was described by his friend Ernest Hemingway as “the finest painter of game birds that we have in America.”

Lynn Bogue Hunt—Angler, Hunter, Artist showcases the complete collection of Hunt paintings acquired by New Jersey sportsman Paul Vartanian. Not only is it the world’s largest collection of Hunt paintings, drawings, and memorabilia, but the largest and most complete collection of the work of any major sporting artist. Shop Now