Willie Boy made his literary debut in the final chapter of The Greatest Quail Hunting Book Ever. The chapter was titled “ A Small Southern Tale,” and it chronicled the comings and goings of a single family of Georgia bobwhite quail hunters in the period following World War II. Young Will represented the legacy of the entire clan, since it was his duty to perpetuate the culture, ethics and traditions that characterize the quail hunting culture of the Deep South. Since then, he has occasionally tripped lightly through the pages of this column whenever his presence was needed.

As you would expect, shotguns were a big part of that culture, and Willie Boy developed a fondness for classic, sweet-handling doubles. Later in his life, he came to own many of them. It didn’t matter the origin. American, English, Italian or other continental guns were all welcome, as long as they were well made, handled well and shot well.

Over the years, folks around there occasionally wondered how a small-town boy from a family of modest means grew into a man with such an affection. It was a little unusual, I guess, since the normal fare of shotguns—in that part of the world at that time—ran mostly to utilitarian, break-open “single barrels” and economy grade doubles with a smattering of pumps and semi-autos that were proudly flaunted by the more affluent members of the community.

Back then, the truly affluent aspired to own a Browning A-5, the most coveted of those being the famed “Sweet Sixteen” version. A few of the unenlightened even accused Will of “putting on airs.”

Nothing could have been further from the truth, though, because the down-to-earth Willie Boy just never had a chance. For him, it truly was a deep affection rather than an affectation. It was only natural, you see, for Will was exposed at an early age, and once exposed to fine doubles, almost nobody ever goes back. Very few people so exposed can ever again be satisfied with lesser fowling pieces.

Will was raised by his grandfather, June Bailey, whose favorite quail gun was a delightful little DHE Parker—the lovely D grade, with ejectors. It was chambered for 16 gauge and built on the 0, or 20-gauge frame. Coming in at a scant six and a quarter pounds, it was perhaps the most perfect quail medicine ever created by an American maker. Its open-choked, 28-inch barrels swung like a dream and its stock dimensions happened to fit Will perfectly.

With exquisite period engraving that featured both dogs and birds to complement the amber- and ebony-streaked Circassian walnut stock, it was a beautiful thing to behold. Of course, being perfect, it had a straight, English style grip and a slim splinter forend.

The Parker was well used, but in well-cared-for condition, as befitted a gun that saw the field often over a period of many years.

Willie Boy had this marvelous instrument in his hands at the moment his grandfather died and, from that day on, it never left his possession. It was an integral part of him, of his life and his heritage.

The Parker wasn’t the only gun that he inherited from his grandfather. There was another. One that had a bit of mystery surrounding it. One that went even further back into his family history. . . all the way back to the grizzled old black gentleman who had taken both his grandfather and his great-grandfather under his wing when each of them was a youngster.

Hilton was the county’s “bird dog whisperer” for untold years, and he tenderly taught the quail hunters’ creed to June Bailey’s father, Jim Bailey and when Jim was disabled, undertook to do the same for June.

Some time in this two-generational tutorial of Bailey men, it seems that Hilton came into possession of an old, double-barreled, 12-gauge hammer gun. Jim never mentioned it, but June recalled it clearly from his first days afield with Hilton.

Hilton rarely shot when he and June were afield, which was virtually every day of the quail season, but he carried it always—without fail. June remembered it as being “long-barreled and graceful,” and “snake-deadly” in Hilton’s hands. According to June, he couldn’t remember Hilton ever missing a quail with it, though he surely must have. But it was just such a rare incident that he didn’t remember it happening.

The gun’s origin was a bit of a mystery. Hilton’s “socio-economic status” was such that it would have prohibited him from purchasing anything but the most basic armament, but Will remembered his grandfather saying that it was a “very nice gun.”

Miss Rosie, the slight, stooped, snowy-haired woman who served as Hilton’s “better half” for many years, recalled that it came in the mail. (In those naïve days, such was totally legal!) She didn’t remember the name of the person who had sent it, but related that Hilton had told her that it was from a woman up north. As the story goes, Hilton had guided her husband for many years, until old age put an end to the man’s field-tramping.

Hilton hadn’t heard from him for several years when the package came with a simple note that read, “George wanted you to have this.”

Hilton meticulously cared for the gun, treating it as if it were his first-born child and firing it only on occasions that were, for reasons only known to Hilton, special to him.

When June last saw Hilton, he asked June to take care of the gun ”until I sees you agin.” Of course, June agreed. What less could he do for the man who taught him nearly every thing he knew?

As far as anybody knew, June never hunted with the gun, but occasionally, late at night, took it from itscase, inspected it before carefully oiling it and wiping it down. Then, only after he was sure that all was well, he would snap the gun together and sit quietly with it across his lap. After a while, he’d shoulder it and make a couple of swings at imaginary birds before reverently putting the gun back into its heavy leather case and stowing it in the back of his bedroom closet.

One day, a few weeks after his Grandfather died, Willie’s ma knocked at his door and upon entering, simply said, ”This was Grandpa’s other gun. It’s yours now, too!”

She then placed the leather case on the foot of his bed and left. Willie Boy had never seen the gun before his Grandfather’s death, and couldn’t find the heart to open the case for more than three weeks.

Finally, one night when he was alone in his room, a momentary vision of hunting with his Grandpa flashed through his head and he decided it was time to see what the case contained.

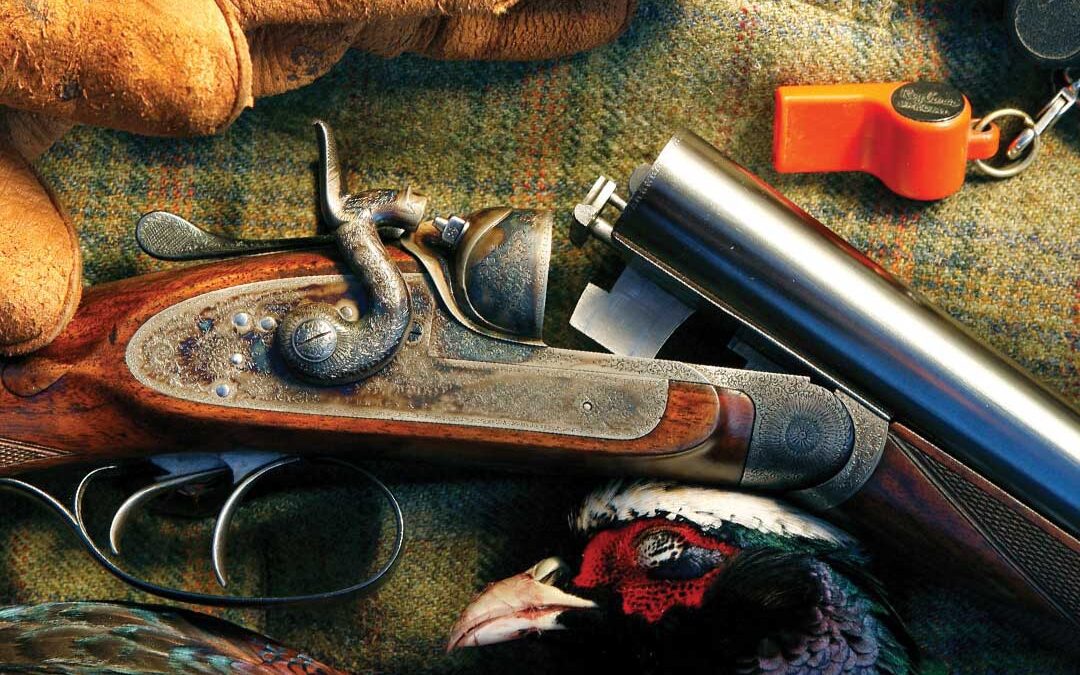

Of course, it was Hilton’s gun, carefully preserved like a gem from a time capsule. It was, as far as he could determine, immaculate, shiny as a new penny and surprisingly devoid of wear from all the time that it had been on the planet. It was a splendid example of the most graceful type of gun ever created, the bar-in-wood, sidelock, double hammer gun.

The stock, which encircled and carefully cradled the locks, was in typical English style, straight gripped with a splinter forend, and the wood was of fine English walnut that glowed with the soft luster of eternity. The locks were engraved with crisp English scroll and floral bouquets, and the hammers stood erect like pointers winding a covey of quail from beyond the horizon.

The long, sleek, 30-inch barrels conspired with the gun’s slight, 6½-pound weight to provide a balance like nothing he had ever felt. The stock dimensions were exactly the same as his grandpa’s Parker, and when he raised the gun to his shoulder, it swung with the ease of poplar leaves floating on an autumn breeze. Even at his tender age, Will already knew a thing or two about shotguns, and he instinctively understood that he held in his hands the product of sheer, unadulterated genius.

When he finally got around to looking for markings, he found two inscriptions on the rib. He wouldn’t fully understand their implications until much later in life. One read, “MADE OF SIR JOSEPH WHITWORTH’S FLUID PRESSED STEEL.” The other proclaimed the maker to be “J. PURDEY & SONS, AUDLEY HOUSE, SOUTH AUDLEY STREET, LONDON.”

Like I said, the boy never even had a chance.