Though Chinese ceramics of 3500 BC depict horses both harnessed and ridden, the archaeological agreement is that the horse was first domesticated in Asiatic Russia around 3,000 BC.

The wild horse of Mongolia, or Przewalski’s horse, as it was named in 1881 by the Russian explorer, still exists in captivity and in small, reintroduced bands in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia and northern Sinkiang. Stocky, zebra-like, the ancient Przewalski likely served as breeding stock for much of the Old World once early hunters discovered more food could be procured from horseback than by simply eating the horse.

Inscriptions on pottery fragments evidence that the Sumerians hunted on horseback, but the oldest detailed scenes are those of the Egyptian Pharaohs which depict the hunter in a chariot, bow drawn at fleeing gazelles. From the 7th century, enormous murals in the palace of Assyrian King Assurbanipal II portray his highness mounted, lance in hand, after lions. The Assyrians were as bloodthirsty in sport as in battle — legend has it that on a single hunt the king slew 450 lions, 200ostriches and 30 elephants. The hunts must have been long and the game thick!

The Romans followed, using greyhounds to flush the game, as did Germanic tribes, Celts and Manchurians. When Rome collapsed, the fun slacked off in that part of the world until Alfred the Great claimed the sport for the upper class and counseled young noblemen “to train themselves in all the arts, but particularly hunting and riding.” It was perhaps the Danish King Canute to whom we owe the first, if somewhat proprietary, game law. He introduced the death penalty for anyone caught hunting in his preserves.

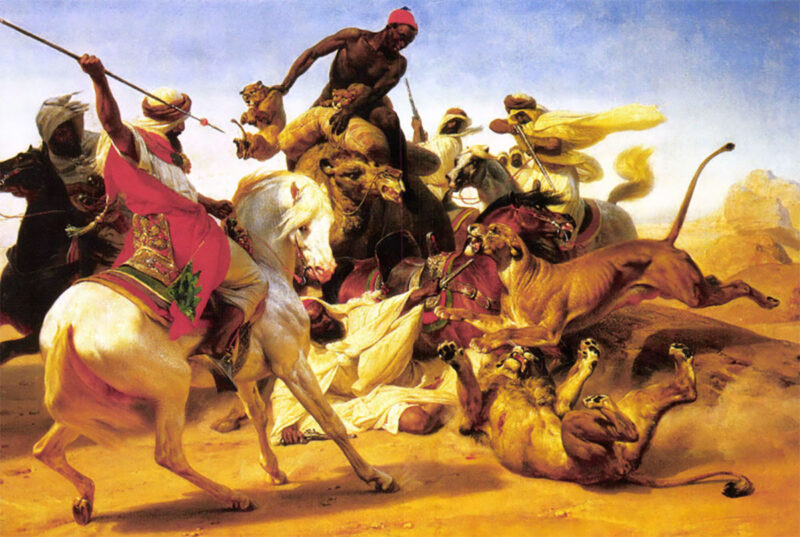

French artist E. J. H. Vernet may have applied a bit too much imagination in his 1838 oil, A Lion Hunt, yet these Arabian horses are depicted with great anatomical accuracy.

In every history book there is a dramatic rendering of Cortez’s landing in the New World with the famous 16 Spanish horses. There were actually 17; a colt was born on the voyage. No castration was practiced for many years and Spanish horses flourished on the new American ranges which were superior in grass and climate to the midlands of Spain and North Africa. Horse populations exploded.

Eventually, the animals found their way into the hands of Indians, first as gifts or in trade, and later as booty. Apache raids around Santa Fe and as far south as Sonora by the Comanche further stocked Indian herds and thus began the Great Horse Culture of the West.

Indians proved natural riders as Custer noted during an attack:

“…the savages availed themselves of their superior, almost marvelous, powers of horsemanship; throwing themselves upon the sides of their well-trained ponies they left no part of their persons exposed….”

So did their women. Captain Randolph B. Macy watched two young Comanche women set out at full speed with lassos in hand after antelope and each rope one on the first throw. So skilled were the Comanches that they boasted the only reason they allowed Spaniards to remain in their territory was to raise horses for them to steal.

Furious Charge of a Buffalo, from Roualeyn Gordon Cumming’s 1850 classic, A Hunter’s Life in South Africa.

If horsemanship came naturally to the Indians, so did hunting on horseback. Buffalo, in particular, could be taken more efficiently. Prior to horses, Plains Indians hunted buffalo by stalking or organizing drives to run them off cliffs. But mounted, they could harvest the exact number of animals they wanted. Historians agree that the use of the horse resulted in fewer animals killed for each Indian they fed and clothed.

The Indians’ buffalo runners were highly valued. Swift, possessed of great stamina, they ran unflinchingly alongside the thundering bison. The rider, guiding the horse with only his legs, drew his bow or thrust his lance. Often a single arrow was not enough, and the hunter was forced to retrieve it at a full gallop and send it again, blood-covered into the fleeing animal’s side. Even for expert riders it was hazardous. Becoming unseated meant a high-speed fall and fair chance at being trampled by the running buffalo. Equally perilous for the mount, wounded buffalo often lashed out at their antagonists and many prized horses ended their hunts gored and dying in the grass.

Following the Louisiana Purchase, the first whites migrated west on The Missouri River. Hunters and trappers had to trade for Indian horses before striking out for beaver and buffalo. To be afoot in that enormous new country was to be nearly helpless and for the next five generations man and horse were inseparable.

Elsewhere, through colonialism, the horse was forced from his element into a stranger, often hostile one, yet was expected to perform as gracefully. In search of larger game, among other things, the British settled East Africa with their horses. A seemingly odd place for those English mounts, tile Dark Continent posed dangers both to the hunter and his horse.

Rhinos were found in unbelievable numbers during that period and often charged the horses when encountered in the bush. Crocodiles lurked beneath the surface of rivers and watering holes, where an unsuspecting saddle horse might bend down for a drink, only to have his muzzle clamped horribly and be dragged under. In spite of it all, dangerous game was pursued on horseback with elan, especially lion, as the following vignette of Livingstone’s friend, Oswell, is recounted by Stanley:

“Upon one occasion, his sport came near ending more fatally for himself than for the lion. He had exhausted the loads in his gun without any effect except to wound the lion, which, enraged by the pain, sprang upon the hind quarters of his horse as he turned to fly over the plain.”

An African horse’s peril was not just limited to attacks by predators, as Teddy Roosevelt writes on his long safari of 1909-1910:

“While on the Guaso Nyero trip we had run into a narrow belt of the dreaded tsete-fly, whose bite is fatal to domestic animals. Five of our horses were bitten and four of them died … ”

A short time later in India, pig-sticking provided food and entertainment for the British officers. In Lives of a Bengal Lancer, F. Yeats-Brown charges his beloved Devil across a branch of The Ganges:

Going to the Meet by George Wright ( 1860-1942)

“The Devil slithers down a sand bank and plunges with a snort of joy into the water. None of the others will face it; there’s an ungentlemanly pleasure in that.

“This boar is a very good swimmer. So is The Devil. I leave his head free, holding the cantle of the saddle and my spear in my right hand, paddling with my legs and left arm. How delicious this cold water feels, through my clothes, down to my boots. With a squelch I am in the saddle again, everything running and dripping. That’s a stone handicap to our friend, but I’ll catch him yet…there’s no skill in riding such country: nothing avails but good luck and a good horse.”

Roads and the automobile changed hunting forever. As land became more and more accessible, many big game animals retreated to roadless areas of the world. As forests were cleared in Europe the principal quarry became the red deer, the hare and the fox. English in style and ceremony, fox hunts still thrive in Europe and most equestrian areas of the United States. Few sights exalt as that of a red-clad troupe gliding over meadows and fences in full cry. In the American South, horseback hunts for quail have become a storied tradition, but it is in the high country of the U.S. and Canada where horses are used the most for hunting — and with great success.

There is something so natural, so rhythmically part of the earth in the way a horse moves over mountain terrain. The sheer beauty of the enterprise is often reward enough for me. Recently, when it came down to a choice for cougar guides, mine was easy. I just asked whether or not they used snow machines. The fellow who told me that he didn’t own one of those damn things was the one I booked.

“I have a bias against ATV’s,” says Roland Cheek, longtime outfitter and former president of the Montana Outfitters and Guides Association. “I don’t trust technology’s answer to evolution. People tend to use substitutes for learned outdoor skills. The best hunters I’ve known from years past didn’t have a fancy gun or vehicle, just a good horse and a well-worn pair of boots. And they didn’t spend their time shopping for this or that gadget. They spent it learning the habits and habitats of the game, mostly on horseback.

Charles M. Russell’s Meat’s Not Meat Till It’s in the Pan.

“We’ll hunt a particular basin on foot but put half the day in the saddle getting there and coming back and often encounter game doing it,” he says. “ATV’s may have a higher success rate, but the hunting traditions aren’t kept alive. Any way you cut it, a horse is a hunter’s transportation -hopefully, to take us away from civilization.”

Wyoming outfitter Ron Dube agrees. “One reason we prefer horses is the romance of the Old West and we outfitters are in the romance business.” Ron often conducts horsepacking seminars at hunting and horse events throughout the West.

“More importantly, using horses further connects us to the animals we hunt. When we kill an animal, it needs to be done respectfully. The Lakota Sioux end each ceremony to the creator with the words Mitiki Oyasin which means ‘all my relatives, the two-legged, the four-legged, the winged.’ In essence, it is the horses that make the hunt sacred.”

Beyond aesthetics, the view from a horse’s back is tremendous, but in the case of nearly every animal I’ve seen mounted, the horse has seen it first. My favorite technique in game-spotting is to be alert to changes in the way a horse holds his head. Sometimes all you have to do is look between his ears. In low light conditions, horses’ eyes are far superior to ours and in total darkness they can literally be a lifesaver. Many a hunter lost after nightfall has been led back to camp by his loose-reined partner. In timber, game often waits at the sound of an approaching pack string – to them, it may just be approaching elk. The scent of the horses easily masks the scent of men.

A horse can take you where nothing else can. In our National Forests and Wilderness Areas (where machines of any kind are not allowed) as well as the remote regions of Mongolia and South America, the horse is not only the preferred mode of travel but the only one. Now, as in Jim Bridger’s time, a hunter must bring his gear and summon a horse to carry the load.

The art of horse packing has changed little since Bridger. The basic skill lies in distributing the weight evenly and comfortably atop the horse. The equipment has improved considerably. Since before Christ, the prevailing pack was the sawbuck. By the 1920s the Decker was developed — both are very much in use today, although nylon and plastic buckle systems assemble easier and eliminate the need for manties and diamond hitches. Then, as now, the load remains about 150 pounds for the average horse but more in a pinch.

My best elk was killed down a steep draw of lodgepole pine, which we quickly named “The Hole.” We sawed a trail through the fallen trees and led down a young mule we knew to be exceptionally strong. He turned out to be green as well and blew up at the dead smell of the quarters we were trying to get on him. The outfitter and I were knocked flat by the mule when he backed off the load and trotted back toward camp. At the top of the draw, my little saddle horse stood, calmly grazing. We threw the spare pack saddle on him and led him down where he stood like a statue as we heaved and grunted both hind quarters into his panniers. It was a load of over 300 pounds and he struggled up out of that hole with twice the heart of that gutless mule. Like any horse, he did it for no other reason than because we asked him to.

There are hunters who hate horses. They have been bitten, kicked, thrown and rolled on. They have been scraped off on passing trees. I believe this is due to the quality of the mounts that end up on outfitters’ strings, mainly grade horses with traits undesirable for ranching or competition. Except for physical problems, I like to think there are no bad horses, just bad habits.

Waiting for the Guns by John Sargent Noble (1848-1896)

A horse may be in poor condition or unresponsive as a result of many inexperienced riders who did not cue him properly. Mistreatment as a colt might have taught him to defend himself against humans. I know such a horse who can be dangerous when approached a certain way. He is otherwise a very good horse, but it would be a clime to partner him with some unsuspecting hunter. The trouble on most guided hunts is that neither horse or rider has much chance to get used to each other. It isn’t necessary to be a great horseman on a hunting trip. You aren’t there to train the horse, just to survive our experience together. Give him the benefit of the doubt, assume he is a good horse until he does something to prove otherwise. He is your partner in the adventure, your means to the game, your hunting buddy. Chances are, he’ll be the one to carry you out of the wilderness should you become sick, injured — your hunt gone to hell.

Last fall, as I started my old quarter horse, Pesty, across a creek, he went suddenly rigid. Two hundred yards ahead and above us a large deer drifted downhill toward the trail. Its head down, I was sure it was a buck on the scent of a doe. How Pesty sensed him was a mystery as his eyes were only about level with the opposite bank The wind came straight for us, so I gave him a little leg. He crept over the rocky bottom and up the banking, looking intently. The deer didn’t see us until he broke from the tall grass to the trail with that all-in-one motion of head going up and freezing.

Something came over me when I saw the sun on those antlers. I dug in my heels and was at a run before the deer moved. When he spun and retreated, flag up, we had closed the gap to about 70 yards. Few things in life are finer than a full gallop uphill. I gave Pesty his head and leaned forward until our faces nearly touched. We climbed the meadow after that gray creature, flying through the sunlight to an older time. Lion chase, buffalo run, Comanche charge.

The deer made it to the woods, and I pulled up Pesty and squeezed his mane. We watched the white flag flicker and die in the trees. Then I turned and headed back to where the creek crossed the meadow, my horse solid under me.

In Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail, Roosevelt records his experiences from his hunting adventures, the people and animals that he encounters, the excitement of the round up, to the everyday life on the ranch. TR’s delightful prose provides a straightforward and very entertaining read. The book is handsomely illustrated with 95 pen and ink drawings by the premier western artist of the time, Frederic Remington.

In Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail, Roosevelt records his experiences from his hunting adventures, the people and animals that he encounters, the excitement of the round up, to the everyday life on the ranch. TR’s delightful prose provides a straightforward and very entertaining read. The book is handsomely illustrated with 95 pen and ink drawings by the premier western artist of the time, Frederic Remington.

Follow B&C founder Theodore Roosevelt during his time in the Dakotas and Montana beginning in 1884. Upon his return from this particular sojourn out west he promptly organized a formal dinner with his friends and colleagues in December 1887 and formed the Boone and Crockett Club. Buy Now