Hippos will fool you. Fat, slow, benign and slightly cartoonish. Except they aren’t.

This two-and-a-half-ton herbivore kills more humans every year than lions, leopards, elephant and buffalo combined. The Big Five should be the Big Six, and the biggest of the lot should be the aggressive, deadly hippo.

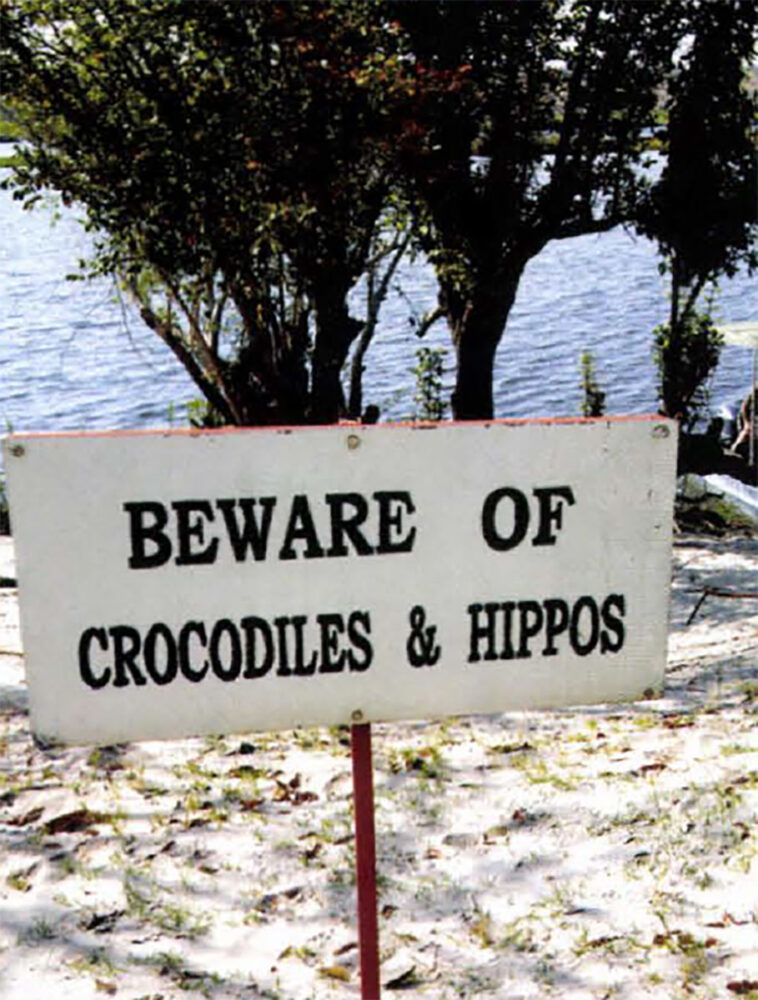

Namibia village people gather wood and raise cattle along the rivers, which are a reliable source of fish and water.

We began hunting Namibia’s hippos in the dark. We drove from Jamy Traut’s tent camp deep into the floodplain grasslands of the Chobe River and its backwaters at dawn. Thirty bumpy minutes later we hit the boat dock on the main river. An hour later we were wending our way amid the reeds, papyrus and phragmites of this fertile bottomland, searching in vain for what should have been one of the more approachable big animals in all of Africa.

”Where are they?” I asked, dumbfounded that we weren’t floating through pods of snorting, yawning, blubbering “water cows” as seen in a nature documentary near you.

Day and night these people must constantly contend with hippos and crocodiles that lurk in and around these dark waters.

“We are a bit too late this morning. They’re already hiding in the reeds,” Professional Hunter Danie Botha explained.

That evening he proved this by pushing the boat into the end of a back channel, hard against the edges of the green papyrus reeds. Our intrusion was challenged by the snorting, basso barking of not one, but several hippos deep in the cover.

We backed off, beached the boat, then tiptoed along the bank, setting up to intercept the beasts if they swam out of their fortress to forage before dark. They didn’t.

“These things aren’t stupid, are they?” I said.

“Not a bit.”

The area we were hunting bordered a national park. Tourists plied the main river in small boats, large boats, and toweling, live-aboard floating hotels that chugged up and down the channel daily. The few hippos that frequented this traffic route took umbrage at any approach nearer than about 50 yards, swimming out to challenge the boat. More than one craft has found itself compromised by hippo tusk holes in its hull.

The area we were hunting bordered a national park. Tourists plied the main river in small boats, large boats, and toweling, live-aboard floating hotels that chugged up and down the channel daily. The few hippos that frequented this traffic route took umbrage at any approach nearer than about 50 yards, swimming out to challenge the boat. More than one craft has found itself compromised by hippo tusk holes in its hull.

“Last year a local villager heard his daughters screaming late at night,” Danie told me. “He rushed out of his hut and right into the mouth of a hippo. It bit his head off.”

This incident weighed on me the next morning when we followed a local fisherman down narrow tunnels through riverside reeds taller than an elephant’s head. The trail of two-foot-deep elephant and hippo tracks had dried brick hard. In places it crossed channels narrow enough to leap across, but our guide would not do so.

“Crocodiles wait there,” Danie said. We detoured, walking on bent reeds over shallow water, past vegetation ripped from the mud by foraging elephants. The pathways narrowed and grew muddy where hippos emerged from their cloistered haunts.

“Crocodiles wait there,” Danie said. We detoured, walking on bent reeds over shallow water, past vegetation ripped from the mud by foraging elephants. The pathways narrowed and grew muddy where hippos emerged from their cloistered haunts.

Our destination was a small lounging pool with a narrow, sandy beach where we hoped to catch a hippo napping. But the wind switched and blew down our necks, right toward the pool. We turned back.

Danie and our local game guard, sent by the tribe to ensure we adhered to all the rules and didn’t stray over the communal boundaries, asked every passing fisherman and herder if they had seen any big hippos. He eventually identified a consistent feeding zone at the junction of two channels.

“My cousin says four big bulls feed there,” he said, sweeping his arm toward a grass flat. “But you must come at first light.”

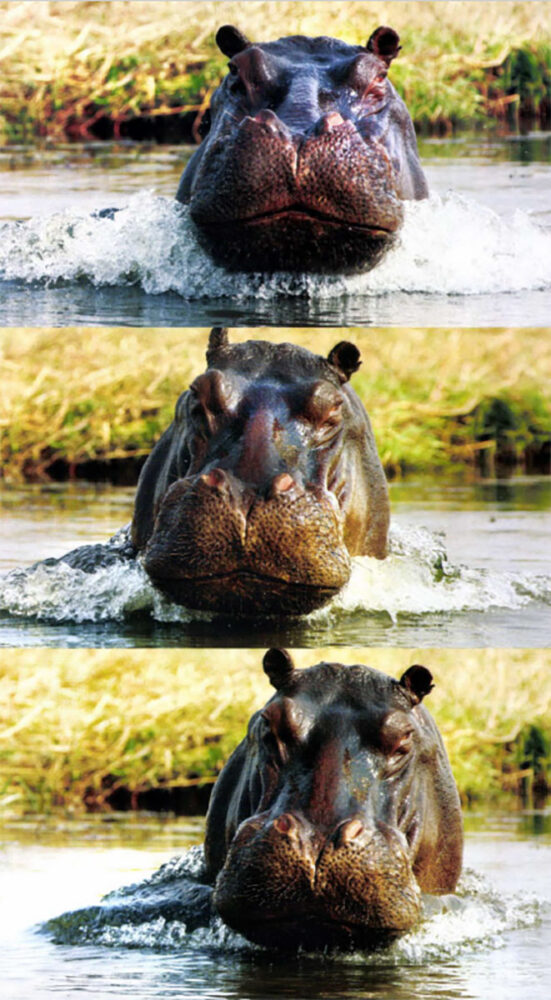

Spectacular spectators, carmine bee-eaters watch a bull hippo as it splashes toward the author. Fortunately, it was only a bluff-charge.

We did. Only one bull was there, already in the water. It sank from sight as we motored around a bend. Danie knew immediately this was our game.

“Big head and all by itself,” he said.

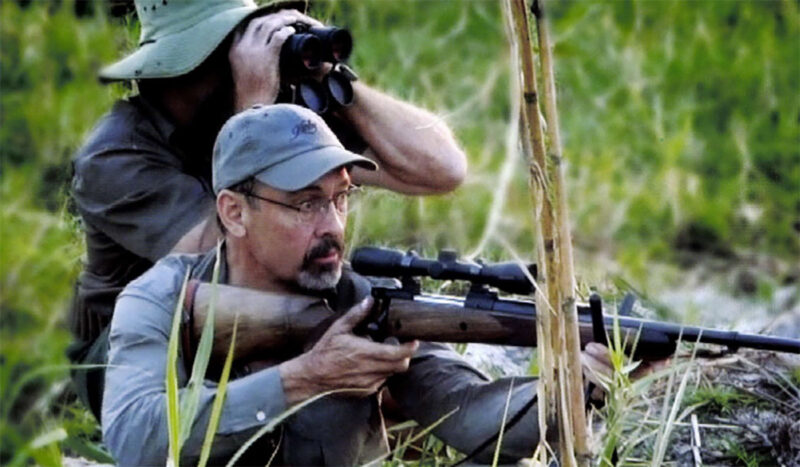

We beached the boat and circled inland, coming out in a stand of reeds near the river’s edge. Then we sat and watched while the bull hippo poked its head out every few minutes for a quick breath and scan. A boat roared past. Later a fisherman poled slowly by in his dugout, a familiar sight to the hippo, which emerged to stare at the disappearing canoe.

When the boatman was safely round the bend, I loaded the rifle and settled behind the scope, the forend resting atop a lightweight, jointed bipod. This would be a precision shot at a small target, the brain between eye and ear, broadside. The bull emerged yet again, within feet of his previous position. I aligned the rifle on the spot.

“One hundred twenty yards,” Danie said.

A dead-on hold for the Kimber Caprivi 375 H&H and its 300-grain Federal Trophy Bonded Bear Claw bullet, which I’d zeroed for 100 yards. The rounds had been landing within an inch of point-of-aim back home. Moments later the broad head popped up again, this time already within the scope and higher out of the water than previously as the wary old bull stared downriver after the canoe. Cranked up to 7X, the Weaver Grand Slam reticle held steadily on a target that, despite the waves and current, appeared to be dead still for a second. The trigger broke and the rifle barked.

“Good shot. No splash in front or behind, so you must have put it in the head. Watch for any thrashing or rolling.”

A dead-on hold for the Kimber Caprivi 375 H&H and its 300-grain Federal Trophy Bonded Bear Claw bullet, which I’d zeroed for 100 yards.

I did. I saw nothing.

“This is a good sign. He must be dead. Now we must wait an hour or two. He will float up.”

An hour and 25 minutes later, while I admired aerobatic carmine bee-eaters swooping over the water, the rounded bulk of a hippo bobbed to the surface, not 10 yards from where it had gone under.

We lassoed the massive, 13-foot-long beast and towed it to a sandy beach where eight men rolled it into water shallow enough for us to appreciate most of its bulk and make pictures prior to the butchering. Long, deep scars marred its back, suggesting it had been defeated by a younger bull and driven from the pod.

After the picture-taking, tribesmen butchered the 3,500-pound animal, leaving only the backstraps for the author’s dinner at camp that evening.

The communal butchers arrived to begin processing the meat. It would be divided among the tribe with just a chunk of backstrap riding back with us to camp. As predicted, the meat was fat-free and delicious, if a bit tough.

Hippos will fool you. But not after you’ve hunted them in the tangled backwater reeds of Namibia’s Chobe River.

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now

Featuring over 50 illustrations by world-renowned artist Bob Kuhn, AFRICA features more than 400 pages of unforgettable stories by some of the finest professional hunters and writers of sporting adventure. Buy Now