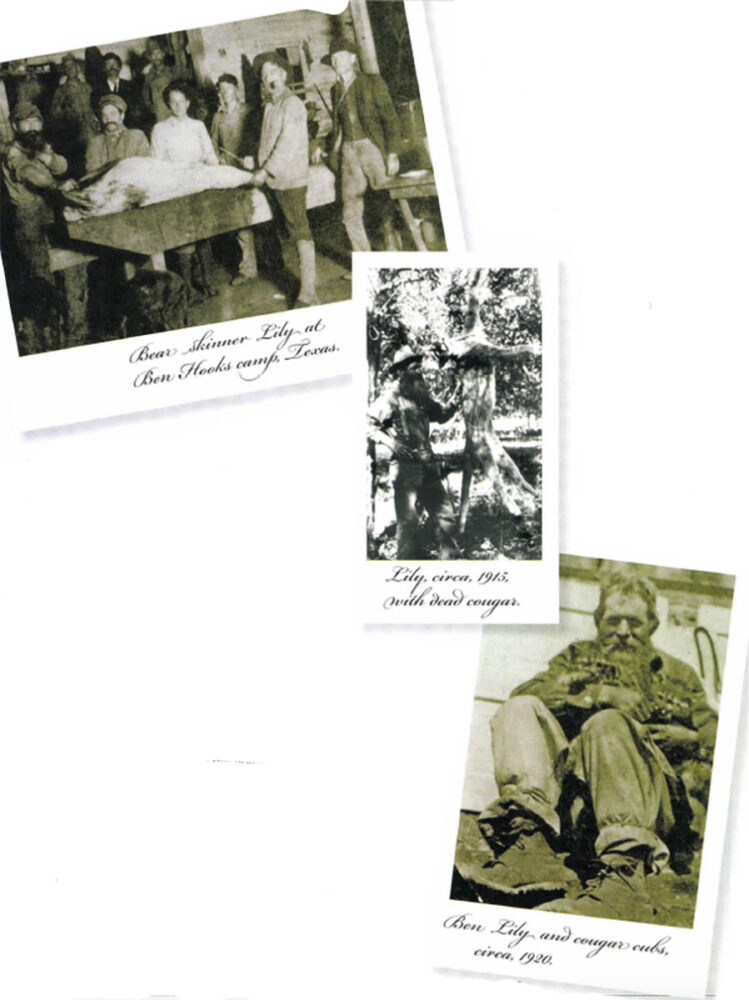

Lily has been viewed both as a legendary hunter and a shameless poacher.

In 1908 residents of Coahuila, Mexico, lived in fear of a large male grizzly that had laid claim to a stretch of road leading into the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Vaqueros in the region avoided moving their stock down the road, which was known as Camino Real. Those who traveled Real were faced with the possibility of a dangerous encounter with the legendary bruin.

That same year, a peculiar white man drifted into Coahuila with a pack of hounds tied to his waist. The man, who was almost 6 feet tall and 180 pounds, sported a full beard and wore tattered clothes, thin leather boots and a weathered hat pulled low around his face. The stranger was quiet and kept to himself, carrying with him nothing more than a rifle, a large knife with an oddly shaped blade and cornmeal. The stranger was a bounty hunter, a man who made his living killing predators for profit on local ranches. Shortly after his arrival he departed down Camino Real into the Sierra Madres. He was never seen by the residents of Coahuila again. Neither was the grizzly of Camino Real.

The houndsman who killed the notorious Coahuila grizzly was Benjamin Vernon Lily. His skills as a tracker and his fearless determination in the pursuit of bears, wolves and lions would ultimately make him a legend from the swamps of Louisiana to the deserts of Arizona.

Born in Alabama in 1856, Lily worked as a blacksmith and farmer before kissing his wife and children goodbye and leaving his cotton plantation to fulfill what he believed to be his sacred duty — hunting down and dispatching what he referred to as “malefic creatures” and “varmints.”

Lily lived totally without the comforts of a home and the assurance of regular meals, opting instead to sleep on the ground or in a tree and to eat whatever he could gather or kill. One of his favorite wild meats was mountain lion, which he ate at least in part to capture for himself some of the cat’s predatory essence.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Lily was widely known as a varmint hunter and houndsman. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt asked Lily to join him on a bear hunt in northeastern Louisiana near the Tensas Bayou.

Roosevelt had oftentimes expressed a desire to hunt bears in the cane brakes, perhaps in part to erase the memory of a 1902 hunt in Louisiana when a bear cub was lassoed and tied to a tree, an act that left him thoroughly disgusted. (The incident would later result in stuffed bears being named “teddy bears” in honor of the President’s refusal to shoot the cub).

Shortly after Roosevelt was escorted to his camp at the edge of the swamp, Lily emerged from the dense palmetto thickets after a 24-hour walk — with two of his hounds in tow. He had not eaten and he’d been without water the entire journey, because he refused to drink from the stagnant swamp.

Roosevelt collected three bears on the hunt, and this time none were bound to trees. No doubt, the President owed his successes to the skill of the wizened mountain man who quietly vanished back into the palmetto thickets at the conclusion of the hunt.

Roosevelt was obviously intrigued by the odd houndsman as he wrote a great deal about him in his journals.

“He could run through the woods like a buck, was far more enduring and quite as indifferent to weather, though he was over 50 years old. He had trapped and hunted throughout almost all the half-century of his life, and on trail of game he was as sure as his own hounds. His observations on wild creatures were singularly close and accurate. He was particularly fond of the chase of the bear, which he followed by himself, with one or two dogs; often he would be on the trail of his quarry for days at a time, lying down to sleep wherever night overtook him; and he had killed over a hundred and twenty bears.”

Roosevelt described Lily as a “religious fanatic” and noted his peculiar habits of keeping his hounds tethered to his body while “sleeping in the fork of a tree like a turkey.” Despite Lily’s peculiarities, Roosevelt was taken by his skills as a tracker and for his incredible stamina. Lily opted to follow his hounds on foot for the duration of the hunt rather than ride mules and horses.” I never met any other man so indifferent to fatigue and hardship,” wrote Roosevelt.

Ben Lily’s reputation followed him as he moved westward into the Big Thicket country of Texas and on to the deserts of New Mexico and Arizona, where he spent most of the last 20 years of his life. Though he hunted most often near the Gila National Forest in New Mexico, he traveled as far north as Idaho and deep into the Sierra Madres of Mexico, always on foot. Some historians credit him with killing thousands of mountain lions and bears. Lily expert and author Dutch Salmon, however, believes a more accurate estimate was 500 cougars and 600 bears, still a sizable number of animals given their relatively wide distribution.

No mountain man of the period could match Lily’s determination and skills as a tracker. His pack, which included a mix of coonhound breeds and Catahoula leopard dogs from Louisiana, remained close beside him until the quarry was treed or bayed, at which point Lily made the kill. On occasion he followed the tracks of a bear or wolf through the night, stopping only long enough to rest his footsore dogs before continuing on.

For killing lions, Lily preferred his Winchester .30-30 lever action and for bears he opted for a lever gun chambered in .33 Winchester. Quite often he abandoned his rifles altogether and used a double-edged knife with an S-shaped blade that cut more easily through the heavy muscle of a bear’s chest. Lily built the knife during his blacksmithing days.

While working as a bounty hunter in Mexico, Lily reportedly cornered a rogue bear and, before dispatching it with his knife, shouted, “You are condemned, you black devil. I kill you in the name of the law.”

Wealthy oil baron W. H. McFadden, who had heard about Lily’s experiences with President Roosevelt and those in the Southwest, asked him to guide his 1925 hunting expedition from the deserts of Mexico into the Canadian Rockies. Lily, along with his favorite hound Crook, met McFadden in Mexico and led the baron on his quest for big game before abandoning the hunting party in Idaho, presumably to head back to the desert southwest.

Most of Lily’s earnings came from ranchers who hired him to exterminate predators on their vast holdings, and his expert services commanded a high price. Despite his relative wealth, he refused to buy land or a house, possessions that he considered damaging vices that led to sin and death. Instead, he lived in the hills with his hounds, sleeping where he wanted and hunting where game numbers were high.

From age 50 to 70, Lily hunted every day of the year (except on Sundays). He remained in good health and continued pursuing lions and bears well into his 70s.

Since the time of his death, Lily has been viewed both as a legendary hunter and a shameless poacher. And while it’s true he made every effort to track down and kill predators on the ranches that paid for his services, he also had a strong bond with Ned Hollister of the U.S. Biological Survey, an organization that would later evolve into the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

In 1916, Lily was hired to collect animals for museums, which he gladly did, carefully preparing the skins so they could be transported by train to Washington. One specimen, a very large male grizzly killed in Arizona, remains on display at the Smithsonian Institution and is one of the last remaining examples of the now-extinct desert bear. Lily’s specimens helped scientists in identifying species unique to the southwest, such as Mexican gray wolves and javelina.

Despite his reputation as a relentless bounty hunter, Lily faithfully adhered to a strict code of ethics. No matter the circumstances, he would not hunt or kill an animal on the Sabbath. Even when trailing wounded game, Lily would abandon the trail on Sunday and not resume his hunt until Monday morning.

After leaving his family in Mississippi, Lily sent a large sum of money earned from selling hides back East to support his wife and children. And while he had no tolerance for a hound that could not hunt, he had great appreciation and affection for any hound that hunted well. Lily carved a special plaque for his dog, Crook, which died along the Sapillo Creek in New Mexico in 1925. The plaque read:

“Here lies Crook, a bear and lion dog that helped kill 210 bears and 426 lions since 1914, owned by B. V Lily”

Ben Lily was 80 when he died at a ranch near Silver City, New Mexico, in December 1936. A bronze plaque honoring him was placed near his favorite hunting grounds near Pinos Altos. Lily’s eccentric lifestyle made him something of an oddity, but his incredible toughness and unmatched skills as a hunter made him the most famous hounds man ever. By forsaking those things his contemporaries considered basic comforts, he gained a knowledge of the wilderness that may never be matched. He spent his life living on his terms, hunting where he wanted, eating what he hunted and living as he pleased. He remains a unique figure in the history of American hunting.

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Finishing the final book in the iconic Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers is the epitome of Sir John Seerey-Lester’s spirit. Filled with over 120 paintings and 45 descriptive chapters, the new 200-page book relives the compelling stories of 25 acclaimed hunters and explorers.

Amid his fight against cancer, Sir John Seerey-Lester was working tirelessly on his final book of the Legends series, Legendary Hunters and Explorers, when he passed away in May of 2020. He is survived by his wife and fellow artist, Suzie Seerey-Lester, who carries his torch with vigor and pride. Buy Now