Night’s chill lies late in Spoon Creek. I slipped into cold wool and left the tent before dawn was a pale smudge. Breath white, I climbed through the timber to a bald top. Oregon’s Izee ranches sprawled in the cedar- and sage-scented darkness below. Opening morning! Ponderosa crowns had yet to catch sun when distant thumps loafed across the hills.

He was there before I saw motion, eye and antler agleam over the bitterbrush. Another step, and my crosswire wobbled to his shoulder. He vanished in recoil.

My first western deer fell to the 270 Winchester. Stocked by Montana gunmaker Iver Henriksen in rosy French walnut, the Mauser I fired that day would lead a long parade of 270s through my gun rack.

Winchester announced its 270 in 1925. While the 2.540-inch case is .046-inch longer than that of the 30-06, the 270 is essentially a necked-down ’06, with identical .473-inch rim and 17 1/2-degree shoulder, the same 1.948-inch base-to-shoulder length. It fits all actions developed for the 30-06. The first commercial 270 rifle was Winchester’s bolt-action Model 54, also new in 1925. Twelve years later, the Model 54 would give way to the Model 70, a commercial hit that gave the 270 a huge boost. It soon ranked second in sales among the 70’s dozen charter chamberings, 22 Hornet to 375 H&H. Of 581,471 Model 70s shipped before the rifle’s 1963 overhaul, 208,218 were barreled to the 30-06, and 122,323 to the 270. No other cartridge on the Model 70’s long roster by that time came close in sales.

The 270 had arrived as bolt rifles, tested by the Spanish American War and WW I, were gaining traction with hunters. By 1922, Winchester engineers were drafting the Model 54. It had a trim action that cocked on opening. Receiver, bolt, extractor and flag safety mirrored the Mauser’s; but its coned breech took inspiration from the 1903 Springfield. The Newton-style ejector didn’t require a slotted locking lug. The 7 3/4-pound Model 54 had a nicely contoured 24-inch nickel steel barrel. The trim stock featured a schnabel forend, a shotgun butt and a low comb for open-sight aim.

The 54 was hardly perfect. Its trigger was also the bolt stop, drawing frowns from competitive shooters. The safety didn’t operate under Weaver’s 330 scope. Still, the 54’s debut price of $49.50 was no higher than the cost of “sporterizing” a Springfield.

A few years ago, a fellow showed me his only rifle, a scarred Winchester 54 in 270. The stock had been chopped for a pad, and a lace-on cheek-rest added. Bolt and safety had been altered to clear a scope. “Fire it if you like,” he said, “if you have ammo.” I smiled. As 130-grain Winchester Power Points nipped a 1-inch group, I imagined the rifle’s first buyer thumbing crumpled bills. When discontinued in 1936, the Model 54 had sold for $59.75.

Jack O’Connor, Outdoor Life’s shooting editor from 1942 to’72, gave the 270 early and repeated kudos. A Sonoran whitetail that “turned clear over in the air and hit like a bag of potatoes” impressed his Mexican guide Zefarino.

“Whoopee! One shot and the buck doesn’t move. How do you call it?”

“The 270.” Jack replied. “It shoots a good ball—a very fast ball.”

O’Connor’s stature as a gun guru for the nation’s most celebrated outdoors magazine gilded his words on the 270, and have been credited with giving it commercial life. Jack’s first 270 was a Model 54, acquired in its debut year. He installed a Lyman 48 aperture sight and had the rifle re-stocked by R.D. Tait of Dunsmuir, California. A few years later, Phoenix barrel-maker Bill Sukalle sold Jack a flat-bolt Mauser with a 270 barrel for $35. Wisconsin stocker Alvin Linden contributed “plain, straight-grained but very hard and stable Bosnian walnut superbly shaped and checkered” for $75. Frank Pachmayr added a 2 1/2x Noske scope in Noske rings on his own base. That rifle, wrote Jack, “made a real 270 fan of me.”

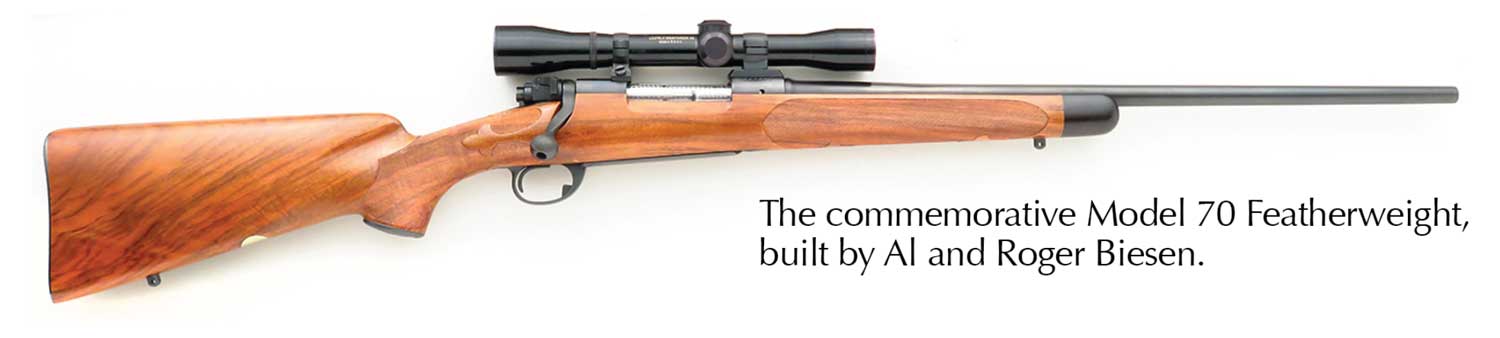

This limited-issue O’Connor commemorative Model 70 270 was built for the Jack O’Connor Center.

First offered in 30-06 and 270, the Model 54 would add eight more chamberings. They were, in order of increasing rarity: 22 Hornet, 30-30, 250 Savage, 7×57, 257 Roberts, 220 Swift, 7.65×53 and 9×57. Sporter versions of the 54 outsold nine others, including Target and Sniper models with Marksman-style stocks, scope blocks and leather slings.

Cheers at the New Haven plant for its first successful bolt rifle were short-lived. The stock market collapse in October of 1929 sent Winchester Repeating Arms toward receivership. On December 22, 1931, Western Cartridge bought the company. But Western CEO John Olin liked the 54. He asked T.C. Johnson and his staff to refine the rifle they’d engineered. They gave it a beefier “NRA” stock and in 1932 added a “speed lock.” Model 54 production continued at a trickle for five years after Winchester’s first Model 70s were finished late in 1936. Of 52,029 Model 54s shipped, 49,009 were boxed by the end of that year.

Oddly, writers for contemporary gun rags, like Ned Crossman and Field & Stream’s Paul Curtis, gave the 270 little attention. O’Connor once noted that Major Charles Askins, his predecessor at Outdoor Life, never wrote about it. American Rifleman didn’t publish a feature-length review until the 270’s third year at market. Townsend Whelen and Sports Afield’s Monroe Goode reportedly did better by it.

In retrospect, Winchester’s choice of a .277-inch bullet must have seemed strange. No small arms of that day fired such missiles. The .264-inch bullets of the 6.5×54 Mannlicher-Schoenauer and 6.5×55 Swedish had exemplary records on game and in military service, as did .284-inchers sent from the 7×57 Mauser and 7×64 Brenneke. But instead of opting for a 6.5/06 (later hailed in wildcat circles) or 7mm/06 (to appear in 1957 as the 280 Remington), Winchester went rogue.

Perhaps America’s most celebrated rifle-maker wished a uniquely American cartridge, in name and measure removed from bullets that had bloodied U.S. troops in 1898 and 1918.

Designed for stout bolt actions, the 270 was stoked to higher pressures than many contemporary rounds, including the ’06. At an advertised 3,140 fps, the 270’s 130-grain bullets got off the blocks faster than 87-grainers from the 250 Savage and passed 300 yards clocking 2,320! But not all hunters swapped their saddle guns or woods carbines for 270s. Complaints that speedy spitzers from the new round ruined too much venison had merit. Some early 270 bullets were prone to fragment at impact speeds near Mach 3. But when Winchester responded with a 150-grain bullet throttled to 2,675 fps, nobody bought it! Flat arcs and killing hits at distance drove sales. A potent 150-grain load arrived in 1933, a thin-jacketed 100-grain bullet four years later.

Remington didn’t leap to chamber the 270, leaving it off the cartridge roster of its first successful bolt-action, the Model 30A (1921-1941). The 30A and its variants in 30-06 sold well; the 7×57 and 257 offered hunters milder recoil. Finally, in 1948, Remington gave the 270 its due, as a charter chambering in the new Model 721 rifle. The 270 would remain popular in the M700 to follow. Meanwhile, in 1958, Savage introduced its Model 110, in 243, 308, 270 and 30-06. Short years ago, I met a hunter with an early 110 in 270. Checkered walnut, open sights. A well-sculpted rifle that came instantly on target. The bolt ran silkily. In 1959 it had fetched $109.75.

Since 1958, Remington has barreled slide-action rifles to 270. Browning and Remington have built 270 autoloaders, Ruger and Browning 270 single-shots. Browning lists a lever-action 270.

Loaded to maximum average pressure of 65,000 psi, the 270 hurls 130-grain bullets at more than 3,050 fps.

Hunters of the 1920s must have thought the 270’s slim 130-grain missiles pitifully small. Thirty years earlier, the smokeless 303 Savage and 30 W.C.F (30-30) had challenged skeptics with bullets of 160 to 190 grains, on the heels of blackpowder repeaters firing bigger bullets twice that heavy! Not until the 270 proved itself on tough game would hunters comprehend the lethal effect of high velocity.

Winchester’s Model 70 brought that proof back from the field, though many hunters were slow to respond. Blame the deep scars of Depression, which throttled sales of luxuries like new rifles. A 1939 elk hunter survey conducted by Washington State’s Department of Game collected not only harvest data from 1938, but cartridge preferences of the hunters. The 30-06 was named most often. The 30 W.C.F. and 30 Remington (not broken out but almost certainly present) matched it, ahead of the 30-40 Krag. These four rounds appeared on 1,372 of 2,285 responses—60 percent! Cartridges of blackpowder lineage showed up more frequently than expected: 11 of them, on 104 returns. Astonishingly, the top 15 of the 44 cartridges named did not include the 270! Well into its second decade, having taken many elk, it was used by only nine respondents—same as the 44-40 and 22 High Power!

My surveys of the 1990s showed legions of elk hunters had by then discovered the 270. No 32-20s in my results! The 30-06 shared the top of the popularity chart with Remington’s 7mm Magnum. The 270 and Winchester’s 300 Magnum came next.

Elk I’ve seen shot with the 270 bury the claim that it’s marginal for elk. After hours following a big Utah bull, a client and I saw it enter hillside aspens. In dusk’s fading light, our chances for a shot there were poor. But as the ridge above it was steep and open, I suggested posting below and 150 yards shy of the copse. As shooting light drew to a close, a twig snapped. “Be ready!” I hissed. The bull eased from the shadows, great ivory-tipped antlers rocking with each careful step. My client must have been as breathless as I but, at the crack of his 270, the bull reared up like a horse, then fell backward, planting its antlers in the earth, dead belly up.

In a broad Wyoming basin in the fall of 1944, O’Connor slipped within range of a heavy-antlered elk. His 270 carried handloads with 160-grain Barnes bullets jacketed with copper tubing. At the shot, the bull collapsed. “Since then,” Jack wrote later, “I have used the 270 for elk almost exclusively.” Most of them fell to 130-grain bullets.

A ranger culling elk for Colorado’s Division of Wildlife reported clean kills with his favored 270 and said its mild recoil enabled him to keep shooting accurately, without a flinch.

While the 7mm Remington Magnum has stolen some of the 270’s market share, both cartridges remain popular. A decade after that 7mm’s 1962 debut, Colorado hunter Anton Purkat picked up the track of a small band of elk in a Chaffee County canyon. It was Sunday, the last day of the season. Careful not to blunder into the animals, Anton was close when the herd bull burst from cover. Three quick shots from his 270 ended Anton’s hunt. He was home in time for church, with antlers that would tape 380 inches!

Few Colorado hunters have put both mule deer and elk on the Boone and Crockett Club’s all-time records list. Dale Leonard is one. He’s also one of the 270 faithful. On a snowy day in 1961, easing along high on a timbered ridge, he spied an enormous elk peering back at him under pine branches a stone’s toss ahead. When he fired, the bull wilted. On a cold morning 15 years later, Dale and three friends fanned out on an Eagle County ridge to hunt mule deer. Dale wasn’t quick enough to tag the wide-racked 5-point that rocketed from its bed and over a ridge. By mid-afternoon, his companions had killed fine bucks. The last was one of a trio. Dale hiked at speed after the other two. A half-mile on, he saw them as they paused on a cedar ridge. Dale flopped prone. One shot from his 270 brought him antlers with a 32-inch span and a B&C score of 200!

My 270s haven’t killed animals with bone like that. But they’ve neatly taken big-bodied deer and elk. Once, high in Oregon’s Wallowa Mountains, an alert deer 300 yards below steep basalt gave me no chance to “go prone.” I dropped to my fanny, a taut sling taking the worst of the wobble from the Model 70. The crosswire in its 3x Lyman paused briefly atop the buck’s shoulder, and the trigger broke. In the vastness of the basin below, the 270’s report seemed a mere snap. But my 130-grain Sierra pierced both lungs. The deer made a couple of jumps, then crumpled.

Another time, a buck climbed a steep, snowy-laced slope above me as, out of breath, I dropped to the rocks and wrestled the Winchester’s muzzle skyward. The 2 1/2X Alaskan offered but a glimpse of the animal, quartering off behind a chimney. I forced the rifle over to cover its exit. There! The Lyman’s dot bounced toward rib, and I pressed the trigger. At the 270’s bark, the deer vanished again. Silence. Then a rock rolled. The buck tumbled in its wake, heart-shot.

Years later, on another hill, I had sat to rest after a long hike. Suddenly a bull elk broke cover 80 yards off, across a steep stringer meadow. As he raced down toward conifers below, I snugged the sling and swiveled to track my target. Almost too late, I swept the post hard past the bull and fired, my trigger press more a frantic tug. The 150-grain Partition caught the bull just shy of timber. He flipped, heels over head, landed on his knees and slid on his nose.

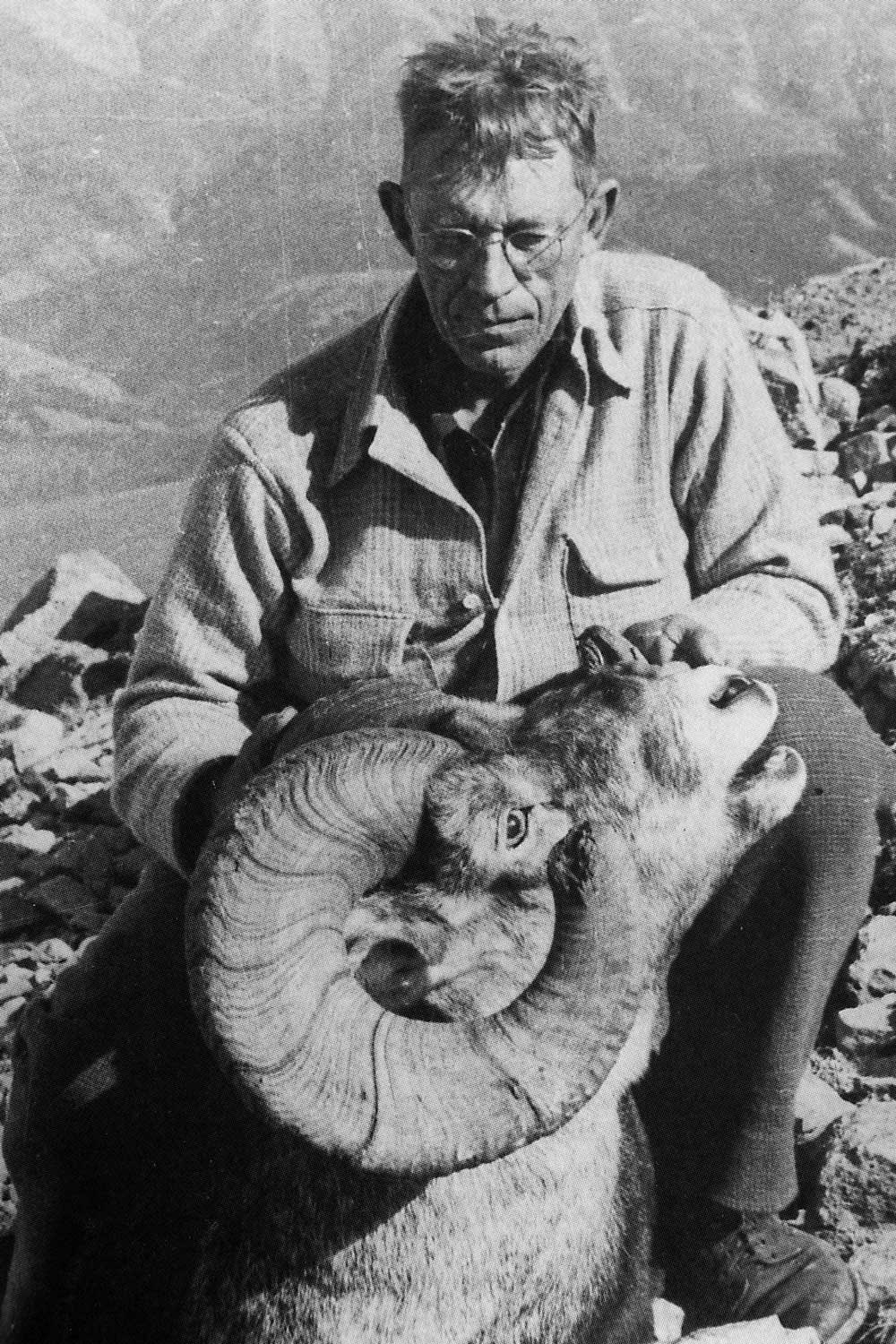

Jack O’Connor used the 270 to take at least 38 game species and one year reported firing 10,000 rounds at the range and afield. His first Model 70 270, bought in Tucson in 1943, then stocked by Alvin Linden, went on a Canadian pack trip wearing a Weaver 330 scope. It downed Jack’s first mountain goat, bighorn, caribou and moose. In 1953 Al Biesen shortened and turned down a standard M70 barrel to build Jack a lightweight 270. With a 4X Kollmorgen in Tilden rings, it claimed a big Dall’s ram in the Yukon.

In 1959 Erb Hardware in O’Connor’s adopted home town of Lewiston, Idaho, sold him a Model 70 Featherweight (first available in 1955), which Jack took to Biesen with the instructions: “Make it like the other one.” Under a 4X Leupold Mountaineer in Buehler mounts, “Number Two” became his favorite 270, accounting for three Stone’s rams.

“I have shot more rams with 270 rifles than with anything else [and don’t] know of a better sheep cartridge,” declared Jack. His international use of the 270 took none of its sheep-country shine.

The Biesen Connection

I knew the Spokane, Washington, gunmaker well. “When O’Connor started writing,” Al told me, “I offered to build him a rifle. He sent a Titus barrel, a Springfield action. I put them together and stocked the rifle. He didn’t like it, so I made him a 30-06 on Mauser metal.” It was a start.

Al Biesen had grown up in Wisconsin. “Early on, I worked in a blacksmith shop. I had to furnish coal. It cost $3.25 a ton, so I gleaned some from a Milwaukee roundhouse. I learned to shrink steel wheels on wood-spoke rims and once shoed a team of Clydesdales in 28 minutes.” Al began hunting deer with a $5 DCM Springfield. “I moved to Spokane in 1948, bought my house for $8,000, later sold it for $10,000, bought it back for $6,000….” In its basement, Al built rifles to support his family. O’Connor’s “Biesen” 270 Featherweights were known world-wide, drawing clients like Iran’s Prince Abdorreza Pahlavi. Al’s son Roger and grand-daughter Paula worked with him into his retirement.

A tireless advocate for the shooting sports, Al officiated at prone matches I fired in Spokane.

“O’Connor made me the most famous gunmaker in the world,” said Al at the writer’s passing in 1978. Anyone who’s handled a Biesen rifle would credit Al, too. He died in 2016.

The 270’s early appeal was due in part to ambitious factory loads. The year before O’Connor got his first Biesen-built 270 Featherweight, Winchester listed 130-grain Silvertip and Open Point Expanding bullets at 3,140 fps, 150-grain softpoints at 2,800. A 100-grain softpoint, since dropped, sped off at 3,580! My Oehler chronograph shows some factory ammo matched published speeds. A 130-grain Federal load posted at the now-standard 3,060 fps clocks 3,020 from a 22-inch barrel. Another, from a 24-inch barrel, kisses 3,100! A competitor’s 130-grain load, however, falls 130 fps shy of 3,060 with a 24-inch launch!

The 270 excels hurling bullets of 130 to 150 grains. For heavy game, I’m sweet on Nosler’s 160-grain semi-spitzer Partitions. Once, in an inclusive mood, I fired Remington’s 100-grain loads through a 22-inch barrel. Listed at 3,320 fps, they clocked 3,366—and punched a .75-inch delta!

All-copper bullets, and those with partitioned and bonded lead cores, expand and penetrate more predictably than did bullets in early 270 factory loads. Most fly accurately from 1:10-inch rifling, standard in 270 barrels. Husqvarna and Mannlicher-Schoenauer rifles have spun bullets from rifling as steep as 1:9-inch. Long-range-shooting fever has prompted use of long bullets with high ballistic coefficients in short cases such as the 6.9 Western. These bullets beg sharper-than-standard twist; but hunting bullets–including Hornady’s 145-grain ELD-X–shouldn’t.

The 270 is easy to handload. “Card off a case-full of H4831 and seat a bullet” won’t pass muster. Still, the cartridge is forgiving and performs well with a wide range of medium- to slow-burning powders. I use Large Rifle primers and charges that yield 3,000 fps with 130-grain bullets, 2,900 with 150s. To my mind, there’s no point in hot-rodding the 270, no need to hurry throat wear or hike recoil.

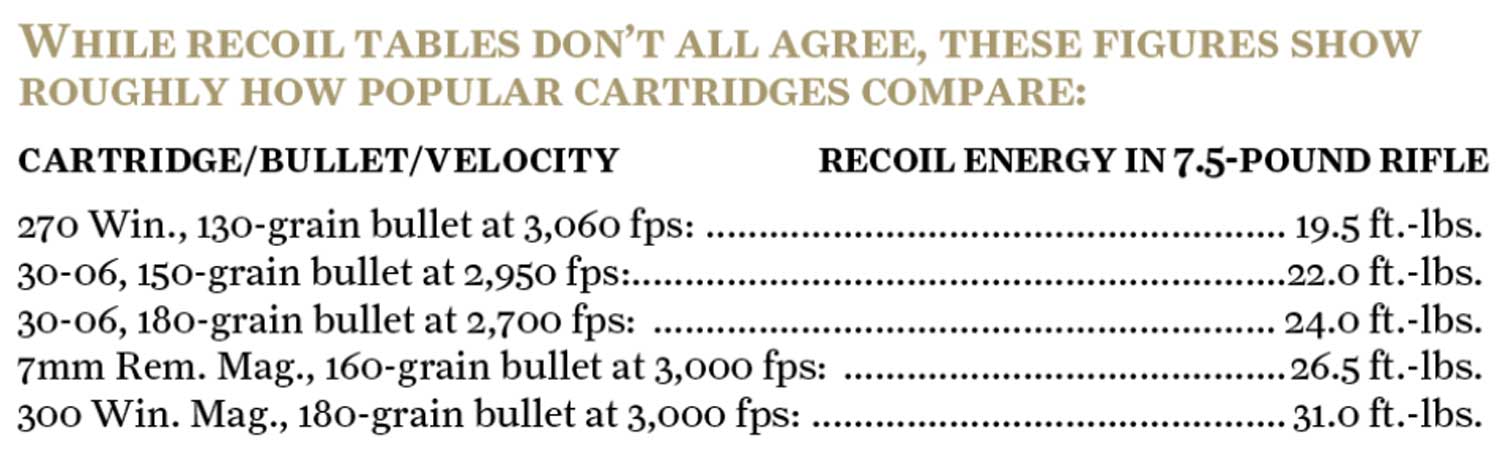

Most shooters can comfortably endure the 17 to 21 ft.-lbs. of recoil the 270 dishes out, though felt recoil depends on variables beyond the load. Rifle weight, barrel length and stock shape figure in, as does shooting position. Does the butt have a Decelerator pad or a steel plate?

With common loads, the 270 Weatherby, 270 WSM and 6.8 Western kick about like a 180-grain load in the 30-06. Add half a pound to the rifle, and recoil diminishes by 10 to 15 percent.

Many 270 rifles have left me since that first Henriksen-stocked Mauser. An early Model 70 isn’t going anywhere. Its blue is nearly gone. The Pachmayr pad on its fencepost walnut has cracked with age. But the bolt is buttery in its race, and no matter the target or load, bullets find the center of its Lyman 3X.

Rifles by Bergara, Cooper, Tikka have also kept the 270 flame alive here. Not long ago, I spied in a gun-shop’s “used” rack a short Remington Model 700. The metal had very little wear. Manufacture of these early rifles with 20-inch barrels lasted only months at Ilion before 22- and 24-inch barrels appeared. I had never owned a carbine-length 270. What better reason to buy one? The stock now nicely restored, it will get an aperture sight, perhaps a 2 1/2X scope tucked low. It is a fetching rifle, and nimble. It cheeks quickly and points itself. And it hurls a very fast ball.

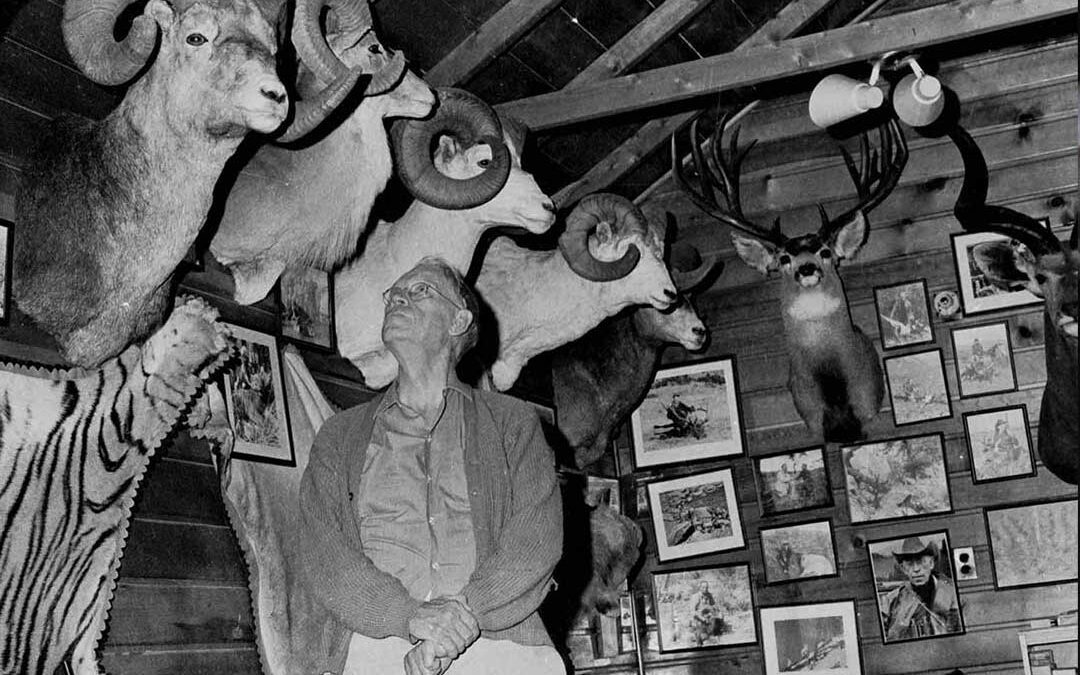

The heyday of the 270 and its most famous enthusiast live on at the Jack O’Connor Hunting Heritage and Education Center just south of Lewiston, Idaho. There you’ll find a rich store of hunting memorabilia, including taxidermy from O’Connor’s long hunting career, plus his and wife Eleanor’s pet rifles and favorite photographs. In a state park overlooking the Snake River, the Center includes a gift shop and meeting room and is open to visitors year-round.