He caught a glimpse of something white among the herd, its body illuminated by the setting sun–he recognized the animal as an extremely rare white bison.

The fall was changing into winter and the buffalo hunters were getting ready for the huge herds to gather on the plains. For the past ten years, the annual bison hunts had become big business, which was quickly eradicating a prime food source of the Indians and indirectly clearing the way for the white man to settle the West.

In 1876, on the Texas plains not far from Fort Worth, two brothers were getting ready for their big hunt. That year they had joined a huge hunting outfit, which had set up camp on Foil Creek about four miles from Fort Griffin.

The brothers were J. Wright Mooar, one of the best-known buffalo hunters of the American frontier, and his brother, John. Unknown to them, the men were about to embark on a buffalo hunt like no other.

They remained camped at the fort for several days before their massive caravan set out to the west in search of buffalo. Led by Wright on horseback, the caravan consisted of four, nine-yoke teams of oxen and 13 wagons, four mule teams each with two wagons. The caravan also employed nine teamsters, skinners and other men who were capable of undertaking various duties such as tending to the camps.

Although the expedition was quite considerable in size, only one man would do the hunting. He had to be sufficiently skilled to accurately take down the beasts without causing a stampede. In this case, Wright Mooar was the hunter.

Wright was a skilled stalker and shooter. With his Sharps rifle, he was able to judge distance accurately and take into account not only wind direction and velocity, but also adjust for the undulating terrain. If his target was a great distance away, Wright was able to take the shot and visualize the arc needed to hit his target.

When they set out, John Mooar traveled slowly at the rear of the caravan, looking after the ox teams. The caravan pushed on through a valley between the Colorado and Brazos rivers toward a place where the wooly beasts would be grazing.

Soon they were heading into an unknown trackless wasteland beyond Fort Concho (now San Angelo). At times, Wright and the mule train would venture a day or two ahead of his brother, so at each camp along the way, he made sure his mules left a clear track for his brother and the oxen to follow. Following the Brazos, Wright maintained a good pace as he headed toward a distant range of hills then past the town of Sweetwater until he reached the plains.

Finally, they arrived at a vast stretch of open prairie covered with grass and brush, where in the distance they could see several lakes and ponds. Wright knew this was ideal grazing land for buffalo and he felt confident they would soon encounter one of the big herds.

Wright pressed on, turning south toward Deep Creek, which would eventually be the chosen site of the Mooar Ranch.

As the sun was rising the morning of October 7, 1876, Wright and his party came upon their first herds of bison. While his men set up camp, Wright spent the day riding and surveying the country and the herds in the area. Just before sundown he found a sizable herd of bison. He rode to the top of a ridge to get a better look and noticed they were only about one and one-half miles from his wagons.

Satisfied the herd would still be in the area in the morning, he started back to camp. As he headed down a prairie hillside, he caught a glimpse of something white among the herd, its body illuminated by the setting sun. After stopping and taking a closer look, he recognized the animal as an extremely rare white bison.

In his long hunting career, Wright had only encountered one other white buffalo. He immediately gave spur and rode hard back to camp. When he arrived, he was told that the buffalo had apparently been there some time, but no one had seen a white buffalo in the herd. On hearing this, Wright told his men to get their knives and follow him.

Because their quarry was so near, he led the men on foot down into the creek toward the herd. They traveled the first few hundred yards under the cover of a high bank, then crept onto the open prairie just as the sun slipped toward the horizon.

The skinners stayed back, while Wright edged toward the bull, crawling on his hands and knees. Creeping through the grass, he got as near as possible to the wooly creature, which turned out to be a cow.

As Wright readied himself for the shot, he turned to his amazed companions and in a low whispered voice said, “Take a look. There is the gamest animal on earth. A white buffalo.”

With that, he turned towards the beast and raised his heavy Sharps rifle. As he pulled the trigger, Wright may not have known that the white buffalo was one of the rarest animals in the American West or that only one in ten million bison are born white. He may also have forgotten the words of one spiritual leader who said, “A white buffalo is the most sacred living thing you could ever encounter.”

At the crack of the big gun, the white bison fell, and the herd rushed together at such speed that Wright and his men were nearly trampled. Wright was forced to kill three bulls to prevent he and his men from being injured or killed.

The men skinned and cut up the cow just as they would any other bison. They hung the meat on some trees until morning, then traveled back to meet up with John Mooar. They carried with them one hindquarter of the white buffalo.

Mooar went on to kill some 20,000 bison during his hunting career. In total, between 1868 and 1881, as many as 30 million buffalo were killed for their meat and hides. Many of the more successful hunters such as J. Wright Mooar made a good living and were able invest in land and property after their buffalo-hunting days were over.

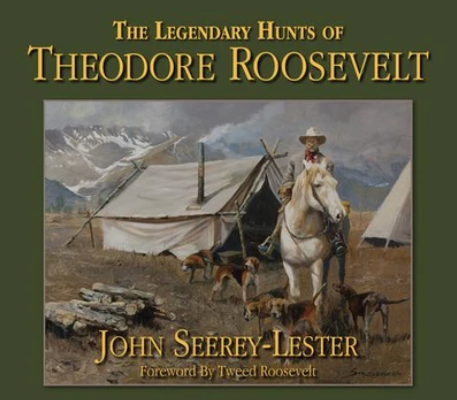

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now

The third book in artist John Seerey-Lester’s ‘Legends Series’ relives in words and paint the exciting outdoor life of Theodore Roosevelt. With his descriptive text and 150 paintings and sketches, Seerey-Lester provides a fascinating glimpse into the former president’s life as a rancher and his unrelenting passion for wildlife, hunting, exploration, and conservation. Buy Now