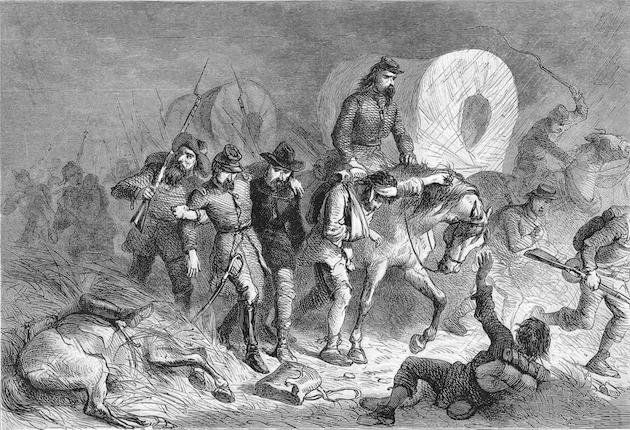

The Civil War began with high hopes and dreams of grandeur on both sides of the line. Soldiers enlisted with delusions of returning home within months, highly decorated and victorious over their enemy. They might even have a small red badge of courage to tell their friends about.

By the end of the four year struggle, more men lay dead than have ever been killed in an American war before or since. The Civil War Trust estimates the number of casualties for both sides at 620,000—roughly 214,000 more Americans than those killed in World War II.

Hunting also changed with the war. A mostly rural South and an urbanizing but still sporting North both had hunting in their blood before the war, but by 1865 those left alive were just trying to stay that way. Former hunters were reduced to eating horse or mule meat, if that. Raiding parties were sent out by both armies to secure what provisions they could, but with tens of thousands of men marching together through the woods, any game animals that had been in the area were long gone before they could be hunted.

When the opportunity did come to secure fresh meat, there was no sportman’s philosophizing done. Anything that could be killed for food was, in whatever way it could be done.

The following excerpt from Robert Critchell’s autobiography illustrates the point exceptionally well. Critchell, a Union sailor, was on his way back from Vicksburg to Memphis on the Mississippi River when he and his crewmates found an opportunity to substitute equine meat avian.

The first day of January, 1864, was the coldest day that I ever knew in the southern country. At Memphis, where the “Silver Cloud” was then lying, the river was full of floating ice of great thickness. The pieces of ice were so heavy, hard and sharp that the steamboats were laid up, waiting for the ice to become soft and of less quantity in the stream, as it was feared the grinding of the ice would cut through the planking of the hull and sink the boats. It was very unusual for ice to be so thick and so hard and in such quantities as far south as Memphis.

At this particular time General Sherman and his staff came to Memphis. He was very anxious to proceed immediately down the Mississippi River to Vicksburg, so one of his staff officers visited the various gunboats at Memphis and made inquiries as to the possibilities of carrying the general and his staff down the river without delay.

Our captain and senior officers decided that it was worth while for us to try it, to accomodate General Sherman. We at short notice got on board a lot of two-inch pine plank, sawed up into two-foot lengths, a lot of long spikes, some hammers, stages and lanterns. The object of these preparations being that, in case the ice should grind our hull seriously, we would by means of the stages dropped over the gunwales, spike on some of these pieces of plank so that they would stand the grind rather than the hull.

Without waiting to get on board fresh provisions, which we needed to supply our distinguished company, we got on our way and, of course, went very slowly, but successfully got down to Vicksburg. We remained for two days, giving us all an opportunity to see the wonderful place which had been surrendered by General Pemberton, C.S.A., to the Union army under General Grant on the fourth day of July, six months before this time. We then started back up the river, but still without any better provisions than we left Memphis with, as Vicksburg was a simple military outpost, and its garrison and inhabitants had been obliged to subsist considerably on mule meat during the latter part of the seige.

While I was on deck after leaving Vicksburg, our boat having proceeded about twenty miles up the river, I saw a small sand island, called in the pilot’s vernacular, a “towhead,” literally covered with geese, ducks and sandhill cranes—the large number being no doubt congregated there by reason of the excessive cold. It occurred to me that here was a chance to lay in some fresh provisions, and, asking the captain’s permission to fire one of my twenty-four pound bow howitzers at this flock of birds, I brought the boat slowly up to the island, as near as I could, without frightening the birds away. I then stopped the boat and fired a gun and, by some extraordinary piece of good luck, happened to explode the shell just on the edge of the island.

The birds of course rose with the sound of the explosion. As near as I could estimate the distance, I had fired the gun at a range of a mile. Our boat being brought to anchor, I went to the island in the cutter and found a large number of dead birds and some fluttering and badly wounded, which the boat’s crew and myself finished, either by striking them with the oars, or shooting them with revolvers. On returning, the number of dead birds we brought, turned out to be forty-three, of which the large majority were geese and ducks.

I had the satisfaction of being patted on the shoulder by our distinguished passenger, General Sherman, and told by him that “we could now have some change of diet,” owing to my good shot. This proved to be the case. We gave the sandhill cranes to the crew, they having a rank flavor and requiring to be boiled, or parboiled, to get this flavor out somewhat, so that they could be afterwards roasted and eaten.

I have often told this story at dinners of naval veterans, etc., but always prefaced it with the statement that “I once killed forty-three geese and ducks with one shot,” which, from the above statement, will be seen was a fact.

Some years ago, I was called on by a little old man at my office in Chicago, who inquired for me with a peculiar high pitched and squeaky voice. I at once recognized him as a man who had been one of the crew of the “Silver Cloud.” He said he wanted my signature to some pension papers he was sending to Washington.

I at first pretended not to be able to reocgnize him, when he pulled from his vest a small black object, which he told me was the skin of one of the sandhill cranes’ feet that I shot just above Vicksburg and that he had brought with him to prove to me that he was the man he claimed to be. I signed his paper with alacrity, on the production of this proof of his identity.

At a dinner of a naval veteran society in Chicago, subsequently, at the Union League Club, where there were several guests invited by the members of the society, I was called on to tell my “duck story,” which, like many sailor’s yarns, was considered by those who had heard it before, as a little bit exaggerated. I was so pressed to tell the story that I did so. When several sarcastic remarks to the effect of “couldn’t I reduce the number of ducks one or two,” were made, to my utter astonishment, one of the guests—a tall, gray-bearded old man—arose in his place and said that “he saw that shot and counted the birds and there were forty-three.”

I immediately said to this gentleman that I was unable to locate him and asked him for some details of his welcome corroboration of my story. He said that he was General Bingham, at this particular time stationed at the headquarters in Chicago of the Department of the Lakes of the United States army as chief quartermaster. He said that in 1864 he was captain and quartermaster on General Sherman’s staff, and was one of the party that we took on our boat from Memphis to Vicksburg.

He had always remembered the great success of that howitzer shell, particularly as it produced a lot of fresh provisions in the shape of geese and ducks, instead of the “salt horse” of which they had had so much and were so tired.

Editor’s Note: This is an excerpt from Recollections of a Fire Insurance Man by Robert S. Critchell (published in 1909). It has been edited slightly for readability.

Cover Image: Thinkstock

Cover Image: Thinkstock