You can spend a joyous Christmas time in the woods. There is peace in the whisper of the pine, merriment in the whirling flakes and music in the north wind’s brawling monotone such as no tawdry human pageant can supply. And when evening falls and the sun has gone, and the wind is hushed and the smoke of the campfire goes straight to the sky, what thoughts so tender and so kind as those we send to the absent ones, over the hills and under the stars?

When Colin, the teamster, drove up to the door on Christmas morning with a rattling span of bays hitched to a stout express, it was still an hour before the dawn; and it had need to be, for we had a long drive of 40 odd miles to Dorsey’s, the nearest house to the barrens of the Gaspereaux and Pleasant Brook.

A light was flickering from the wigwam of the Indian guide, Jim Paul, as we passed through the reservation at St. Mary’s, and that worthy soon appeared with toboggan and snowshoes and silently climbed aboard. By this time the coming dawn had streaked the eastern sky with a leaden gray, that made the wintry world more ghastly than before. The mercury was nearly down to zero, and the bleak north wind moaned over the frozen fields. It would have been a cold and cheerless drive indeed, but for the knowledge that every hoof-beat brought us nearer to the hunting grounds.

The wagon clattered briskly over the ground, and Colin pulled up his smoking team, in good season for dinner, at a wayside house near Little River, 24 miles from Fredericton. From this point it was 19 long miles to Dorsey’s. We passed through the coalfields of Newcastle at 3 o’clock. The sun was throwing long, chill shadows from the crowded ranks of pine and fir that lined the road as we drew up to the farmhouse. Six dogs of highly apocryphal pedigree barked for all, or even more than, they were worth, when we finally halted at the door.

At sunrise on the following morning, the guide and I struck out for the forks of Pleasant Brook 12 miles away where Jim relied upon finding a camp suitable for our purpose that had been erected by a hunting party in the previous autumn. Our material effects were carried on a sled hauled by a team of long-haired sorrels. But the real motive power of the vehicle was Dorsey, whose vigorous use of the English language illumined the way with phosphorescent glow.

For about four miles our route followed a good hauling road that led to the rear of the Dorsey possessions, then it turned sharply to the right over the hummocks of a big bog and traversed a long chain of barrens that led more or less to the north. The sled, from structural weakness of some kind, often broke down, causing Dorsey to rake the landscape with a withering fire of adjectives. Finally, it collapsed altogether about a mile from camp. It was then late in the afternoon. After a few lurid remarks appropriate to the occasion, Dorsey mounted the “off ” sorrel and started on his cold and tedious journey home. Jim strapped a load up on the toboggan that would have taxed the energies of a mule to pull, while I led the way with a modest pack composed of such harmonious ingredients as pickles, tinware and bedding.

We reached the camp at sundown. It was constructed after the Indian fashion entirely out of sapling poles and birch bark, with the exception of a tier of three logs on each side. The interior ground surface was about 14 feet square. There was a kind of door made of birch bark and splints that swung inward from the top, and a liberal smoke hole at the peak of the roof. A fine spring of water rippled across the path only a rod or two away.

Jim slashed around with his axe and in half an hour had plenty of wood for the night. The open fire in the center of the camp was sufficient to keep us warm in the coldest weather, but at times the smoke pervaded the interior in a manner to make existence synonymous with exasperation.

A startling discovery was made when we came to examine our culinary stores, namely, that we had forgotten to bring any plates. The covers of our two tin kettles were pressed into service to supply the defect. Jim complained of a headache and proceeded to concoct some mysterious mixture of herbs in order to drive it away. He said the main thing it contained was calamus root.

“In ole times,” said Jim, “Injin die off like leaves in de fall by de cholera, and nobody know how to stop it. One day a great spirit in de form of a man came to a squaw sittin’ in de door of her wigwam. She was cryin’, for her fader, mudder and tree sons was dead. He tol’ ’im: ‘What’s de matter?’ She tol’ ’im: ‘My fader, mudder and tree sons is dead by de cholera.’ He tol’ ’im: ‘Why don’t you try calamus root?’ She tol’ ’im: ‘How can I tell calamus when I see ’im?’ He tol’ ’im: ‘I’m Calamus,’ and when she looked at him again she saw a plant and flower stan’ in front of her, so she ’membered how dat plant looked like, and she went to Ek-pawk (dat’s head of tide, you know), and dare she fin’ plenty calamus.

“She bile a big kittle full and all de Injins drink, and den no more Injin die. I tell you dat calamus root is great ting. In ole times plenty Injin made pizen out of it and tipped deir arrows for to kill de moose. It killed de moose and didn’t spile de meat.”

When I awoke next morning, Jim was preparing the breakfast. He was baking bread in the frying pan.

“I don’t qualify to ’member of myself for cook,” he said. “When I was huntin’ with gentleman over on de Crooked Deadwater dis fall de bread I cook had a mighty hard name. I tink some of dem sageses [sausages] would go good with de anjovie woosterd,” and he thought right.

As we shouldered our rifles and started for the barrens, the sun broke through the purple mist, and its light, increasing momentarily in strength, rolled over wooded hill and level heath like a golden flood. A walk of two miles over a trail marked with occasional blazes on the trees brought us to the main Pleasant Brook barren. This was a larger barren than any I had ever seen, being about three miles in length and averaging a mile or more in width, while many smaller bays, or pockets, as they might be called, extended to the east and west of the main system. A thin coating of newly fallen snow covered the ground, that would have made the conditions almost perfect for still-hunting, but for the underlying old crust and shell ice that now and then crunched noisily beneath our weight.

No words can picture the desolate grandeur of the scene that burst upon us as we passed through the last outlying fringe of spruce and tamarack at the foot of the ridge, and the big barren stood revealed. It extended straight before us for miles as level as a floor, save where the surface was broken by those peculiar hummock-like elevations of soil, which are the unfailing characteristics of these barrens wherever found.

Before us lay a small frozen lake. Beyond the lake and scattered like islands in the midst of the wintry waste, were occasional shaggy and storm-swept clumps of trees that lent a somber yet agreeable variety to the great white wilderness. In some cases, these straggling groups presented a ghastly imitation of a grove of palms, their withered trunks bare and branchless until near the top, where they blossomed rudely forth into a sort of canopy of grim and scraggy foliage.

Surrounding the whole of this vast area was a solid rampart of barren spruce, surmounted by cheerless, naked knolls, where huge dead trees raised their gray and goitered shafts, as if in hopeless protest, to the skies. The Indian might well be pardoned for believing that Gloscop, or some other deity, in a mood of passion, had here mowed the forest flat in one wide swath of infinite desolation. It was the playground of the prehistoric. It was chaos caught in the act.

We saw few signs of game, and none that were recent, upon the snow-clad surface of this broad expanse.

“Never mind,” said Jim. “I dremp about a horse race las’ night. Sartin when I dream about big animals like dat we’ll see caribou nex day.”

After crossing the lake, we headed straight down the middle of the barren. A few old tracks were seen, but none that were made since the snow fell last night. Soon, however, we noticed a disturbance in the snow ahead, and Jim stooped down to examine a series of saucer-like indentations. So liberal, so lavish in size and number were the signs, so unmistakable in their direction, that they almost seemed to say:

“Now, really, if it’s tracks you’re after, what is the matter with us?”

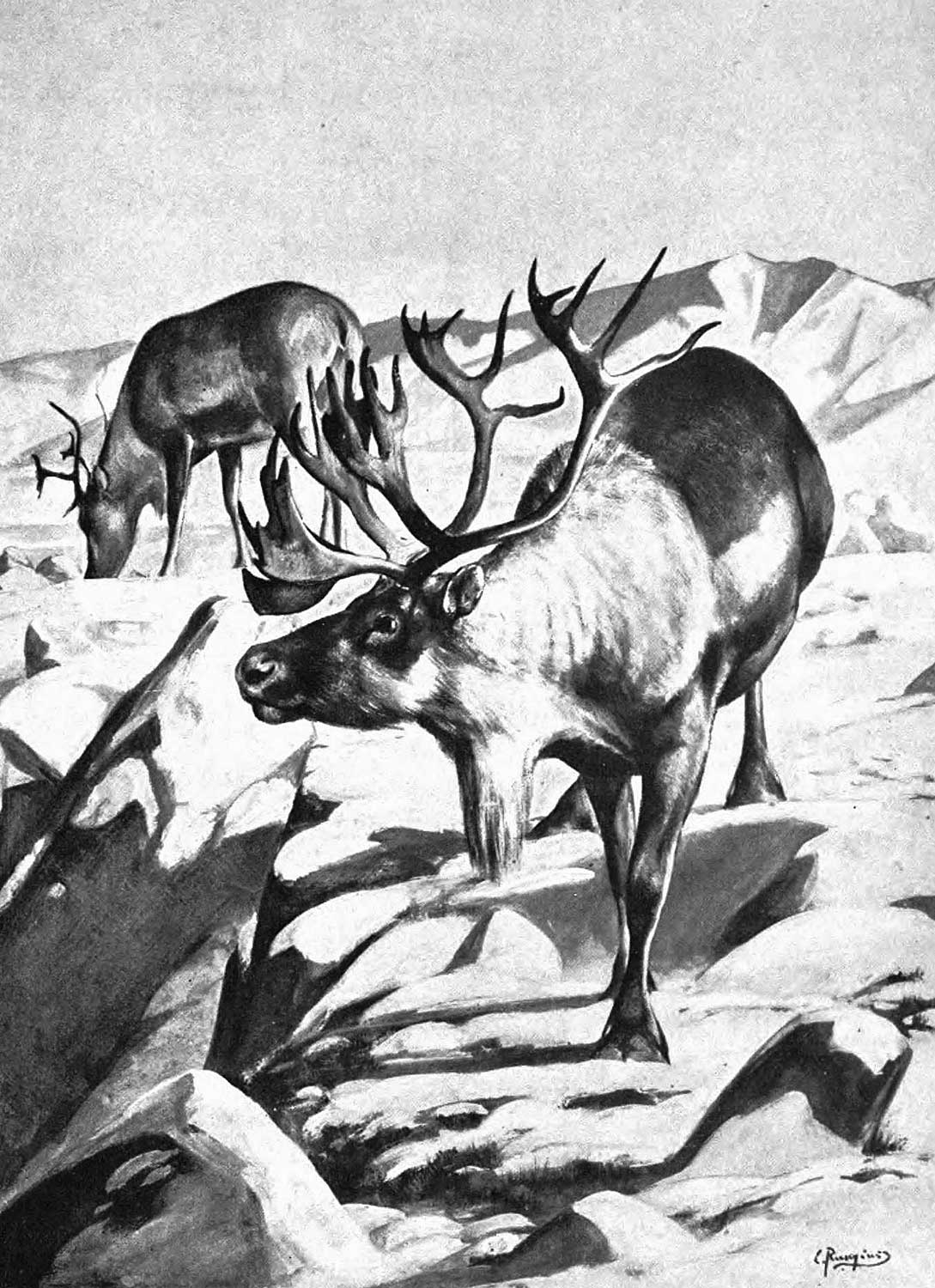

It was plainly the fresh trail of four caribou, one of them much smaller than the others, heading in almost the same direction as we were, for the lower end of the barren. Keeping a sharp lookout for any depressions in the bog that might hide the game from view, we trailed them rapidly. In about half an hour’s time what might be called the summit of the hummocks was reached, whence the barren sloped quite abruptly to the level of a peaty brook. At once I caught sight of a dull yellowish object behind a dead tree that stood some 200 yards down the slope and within a few paces of the brook. It was motionless and different in color from any caribou I had ever seen, yet when I called Jim’s attention to the object, he pronounced it to be a caribou feeding on the moss.

He dropped on his hands and knees and motioned for me to follow. As we crawled briskly down the slope, it seemed to me that the noise made by our passage over the frozen heather and the low-lying brush would surely alarm the caribou. There was no wind and practically no shelter at all of which we could avail ourselves. A moose or deer would not have stood such nonsense for a moment. I had hunted caribou before, but this was my first experience in actually stalking them on the snow. I had yet to learn that a caribou places little dependence on his sight or hearing, but relies almost wholly upon his wonderful power of scent.

As we crept over the intervening knobs of heather, the form of the caribou became more clearly revealed as he industriously rooted in the snow for his evanescent and ethereal fare of reindeer moss. I could no longer stand the pressure and, touching Jim on the shoulder, asked him how far the caribou was away. Jim thought about 150 yards, which agreed very closely with my own estimate. He advised me not to shoot until we got closer, but I was confident I could hit the caribou at that distance.

I had the choice of two rifles, one of them the modern 30-30, the other my old standby, the Martini, known to her intimates by the name of Habeas Corpus [show me the body]. I gave my vote for Habeas, aimed carefully at the living target, allowed what I thought was right for the distance, and fired. Instantly the caribou seemed to squat as though the bullet had grazed his back, then sprang for the cover of second-growth trees along the brookside. The form of a second and smaller caribou appeared for an instant behind a jut of stunted firs, and both of them disappeared like a flash.

I had made two mistakes, besides being the victim of a certain amount of hard luck. It is rarely the case that a caribou will jump at the crack of a rifle, giving no opportunity for a second shot, and it is seldom that they are found so close to cover. My mistakes were that I had overestimated the distance, which proved to be little if any above 100 yards, and had made no allowance for the lift of the bullet in firing down a slope. The next time a muss like this occurs, I shall not allow my bump of sagacity to be trifled with.

We trailed the caribou for a mile or more, two more caribou having, in the meantime, mysteriously joined in the flight, but had to give them up. The ordinary funeral procession is a festive, even hilarious affair, as compared with our return to the camp that afternoon. If Jim did not swear, it was because he knew that the English, French and Milicete tongues combined could not do justice to the subject. It was snowing freely when all was made snug for the night. After supper, Jim smoked his villainous mixture of tobacco and red willow for a long time in silence. Then he asked:

“I s’pose you know de Injin name for caribou?”

“Megah-lip?”

“Au-hauh. Well, de right meanin’ of dat word is snow-shoveler, an animal dat plows troo de snow. Jess de same de right meanin’ of mose (what you call moose) is traveler. Did you ever see a moose dat was mad?”

“No. I have heard that sometimes a moose when fatally wounded will get ‘mad’ and refuse to die, but I don’t believe it.”

“Well, it’s true, jess de same. He won’t die ’til he gits ready. One time I shoot a moose down Gaspro way seven times with my muzzle-load, and after dat he browsed. Every time I fire, he jess roared and stood dare and faced me. Sartin, I tole myself, dat moose is mad, and I went away and lef ’im. When I come back nex’ mornin’ he was dead. Dare’s good many tings mighty crurous in de woods — what you call colundums; I don’t ’stan’ ’em ’t all. Did you ever see a trout dat had turned into a lizard?”

“I never did.”

“Well, it’s true jess de same. I caught a trout one time in a brook up Kingsclear. He had de head and fins and gills of a trout, and he had four legs on him. Odder Injins ketch ’em dare, too.”

From this Jim drifted into the region of the supernatural. He believed in the Christian religion, and also believed in all the old Indian legends.

“In ol’ times,” he said, “de great Injin god was Gloscop. De true meanin’ of dat word is a man from nottin’. He was sent on de world to make peace and destroy all de animals dat took human life. Some of de animals, like de musquash, de red squirrel and de fox he made small, so dey could do no harm. Dare was a big beaver dam at Grand Falls in dem times, and Gloscop broke it with a red pine tree, and let de water down. Gloscop chase two big beaver from de Falls clear down St. John’s River and kill ’em at Milkish. You kin see red streaks and puddles jess like blood on de rocks where Gloscop kill dem old beavers. But dare was one beaver kitten (Winne-jon-sis) dat got away all de same and run up de Tobique River. You kin see two big sea rocks now at de mouth of Tobique dat Gloscop troo at de little beaver to head him off. All de same, dat little beaver got away, and now he lives in de Bay of Fundy. Every day de little beaver raise de water 50 feet high, and every night Gloscop breaks de dam; all de same, he can’t kill Winne-jon-sis, coz he’s so dam squirrly.”

About two inches of snow had sifted down the smoke-hole and covered the ashes of the fireplace when we awoke next morning. On being asked what he thought the chances were for caribou, Jim puffed his pipe reflectively, and then replied:

“Well, dat’s a colundum. I dremp las’ night of fightin’ with a big white dog. Sartin, we’re goin’ to see some- tin’.”

It was much colder and windier than on the previous day, and the conditions for still-hunting could not have been improved. The loose, dry snow that had fallen in the night flowed like a shallow stream over the level bed of the barren before the pressure of the wind. We skirted the eastern side of the big barren this time in order that, if any caribou were feeding on the plain, they might not catch our scent.

The wind booming through the trees so deadened the sound of our steps in the lifting snow that a lone fox, hunting desperately for his breakfast, trotted up within 20 yards before discovering our presence. Then he bounded away like a ball over the hummocks. I took a flying shot at the nebulous mass of red and white as it caromed off a heathy tussock onto the level plain, and by the merest chance in the world rolled him over on the snow.

Jim grinned expansively. “By king,” he said, “if you’d only shoot ’bout half dat good yesterday we’d had dem caribou. Dat’s de white dog I dremp about. We ain’t goin’ to see no caribou today.”

We must have covered 20 miles at least in our wanderings that day.

It was too cold to stop even to eat our lunch. Not only did we make an almost complete circuit of the big barren, but we came upon an old portage road, and followed it fully two miles until we reached the banks of the main Gaspereaux stream. There was not a break anywhere in the mounded snow, save where that rugged citizen of the wintry wilds, the ruffed grouse, had left his aristocratic autograph in the alder hollows, or where the course of a prowling fox was pictured on the path.

“Dare mus’ be big storm comin’,’’ said Jim, “or de caribou wouldn’t lef’ de barrens dis way. Ten times out of one I come on dis barren I alluz see fresh tracks. I don’t ’stan’ it ’t all.”

I remarked to Jim that I had heard that caribou would not cross a human track in the snow.

“Well,” said Jim, “dat’s not true. De only animal dat’s ’fraid of a man’s track is de otter. He’ll go five miles out of his road before he’ll cross it.”

As we were working our way homeward across a narrow plain that lay to the west of the big barren, Jim remarked:

“One time I see a caribou comin’ right down dat path from de big barren straight for us, and I notice dat he walk right agin dose small trees and didn’t seem to take no notice of anytin’. Bambye, when he got pretty close, I shoot ’im. Sartin, he was mighty ole caribou, for he was blind, and had no teeth and no horns. Anudder time I hunt dis barren with one dem English ossifer dudes dat fight in de ’Gyptian war. He tole me dat he could hit a ’Gyptian at a tousan’ yards. Mos’ alluz he walk behin’ me and say nottm’, and when I turn ’roun’ he was doin’ de drill, what you call present arms, shoulder arms, right-about-face, wid his gun. By king, I tot sometime he was goin’ to war wid me, or mebbe he tot I was a ’Gyptian. Bambye I bring ’im up close to a flock of 14 caribou. I tol’ ims: ’Kernel, fire!’ Sartin, dat ossifer fire ’bout 20 shots, and don’t tetch nottin’ but one small little caribou dat was standin’ way off to one side from de rest. He broke his leg, and we had to chase ’im tree miles before we got ’im. I tol’ ims: ’Kernel, I tink you was more scart of dem caribou dan you was of de ’Gyptians.’”

The camp was reached without further incident except that on a burnt pine knoll Jim picked up the newly shed horn of a bull moose.

“Frank,” said Jim, “you take dat home for a curososity.”

We had suffered so much from the smoke of the open fire that Jim went to an old lumber camp two miles away with his toboggan, and returned by moonlight with a superannuated sheet-iron stove and three joints of rusty pipe of as many different sizes. This made the camp much more comfortable than before, besides being more economical in the item of fuel. This night was very cold, the little pocket thermometer I had hung on the birch tree at the spring registering at 9 o’clock 18 degrees below zero.

The next day was warm, still and sunny. Every naked twig and pendent bough in the woodland gleamed and sparkled in the sunlight with untold millions of frosty diamonds and sapphires. Nevertheless, as the day wore on, a bank of lead-colored clouds pushing up from the northeast admonished us that another fall of snow was at hand. We cruised the eastern pockets of the big barren and the ridges that lay between it and the Gaspereaux. One lonely deer track that we followed until sundown, when we had to make for camp, was the only sign of game we found.

At daybreak next morning, there was a liberal deposit of the beautiful on top of the stove. As we opened the door the snow was hurrying down in great feathery flakes that covered wood and barren like a shifting curtain, Jim declared, as he turned the bacon in the pan, that he had dreamed of going to a circus where he had seen so many animals that it must mean caribou, sure.

The wind having shifted to the south, it was decided to give the big barren a rest and work some of the chain of lesser barrens lying along the route by which we had come from the settlement. We circled the edges of several of these barrens without result. There were now about 7 inches of snow on the ground, and the going was rather heavy. At 10 o’clock the snow had ceased falling. We sat down for a few minutes’ rest on a fallen pine and lit our pipes. As I was blowing the snow from the sights of my rifle Jim stood up and stretched himself, took a few pensive steps through the thin border of stunted spruce that flanked the barren, and suddenly came to a full point.

“Caribou! Caribou!” he whispered. “See ’em comin’ down de barren!”

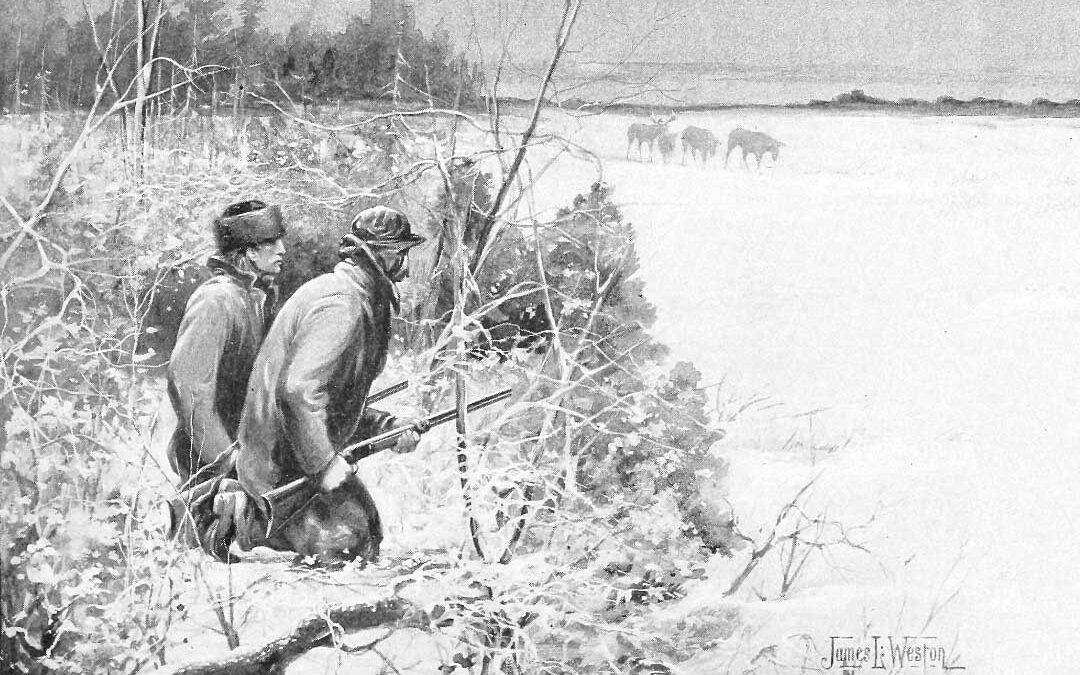

Glancing ahead and a little to the left, I beheld a picture that will last as long as memory endures. Four caribou, almost in single file, were walking leisurely and silently down the center of the little barren and would soon pass directly across our front.

We backed up quickly, yet cautiously, from the rather exposed position in which we stood; scurried on hands and knees through the snow to reach the cover of a bunch of hard-hacks that would bring us as close as possible to the route of the procession, and then I knelt down with rifle cocked until the animals should come in open sight. It was one of life’s concentrated moments.

They approached the ambuscade with a jaunty air, entirely unsuspicious of danger. The direction of the wind precluded the possibility of their catching our scent. The leader was a hornless bull, the second a large cow; then came a two-year-old heifer, while a bull with a fair set of horns brought up the rear.

I decided to pay my particular respects to him. The range was not more than 60 yards. I waited a few tremendous seconds while three of them passed and the rear-admiral hove in sight. As I fired, the fur seemed to fly from his side. The proceedings then became wildly exciting, and I fail to recall with much success the precise sequence of events. I remember that I fired the next shot at the heifer; that the herd seemed to halt in some confusion; that presently the heifer and the admiral were tottering aimlessly about the plain, while the other two were making a hesitating flight for the thick woods to the north; that the big rifle in the hands of Jim went off with a delectable roar within a foot of my ear; that Jim was urging me, in English, French and Milicete, to bring down the fugitives, but that my sole anxiety was lest the wounded animals might escape. I fired at the admiral again and knocked him down, and when I turned to make sure of the heifer, the admiral got up again and set sail for the opposite shore of the barren. However, he soon paused irresolutely as Jim, with a wild Indian whoop, mounted the heifer with his knife. Then, with another yell, and brandishing his gory blade, Jim ran toward the admiral, but that individual was not favorably impressed with Jim, and resumed his struggling flight across the barren.

I fired at long range and broke one of his hind legs. Even then he could run as fast as Jim, and finally the latter desisted from the chase and waved his hand for me to come up and finish him. I ran out on the open plain and, just as the buck was clambering over a fallen rampike on the opposite side, dropped him in his tracks with a bullet through the heart. As Jim was engaged in the process of organic disintegration, he remarked:

“Frank, dat tirty-tirty ’members me of dat fightin’ man, Jim Corbett. He’s a great gun to hit, but, by king, he don’t kill so hard as dem odder Fitzsimmins gun wid de big bullet.”

We left the carcasses lying as they fell, for they were only a few rods from where Dorsey, when he came with his team to bring us out, would have to pass. When Jim had shouldered old Habeas, with the admiral’s liver strung upon the barrel, he was clearly in a blissful frame of mind. As we struck out for camp, he developed a fine stroke of policy, with a view to his future professional prospects.

“Frank,” he exclaimed, “dis barren have no name. Dare’s de Kernel’s barren, Campbell’s barren and Hanbury’s barren, named by de Injins after dem big gentlemen sports dat hunt here long time ago. By king, I call dis de Risteen barren, and as long as dare’s an Injin on de St. John’s River dat will be his name.”

The following day it snowed heavily from dawn ’til dark, and I had fears that our exit to the outer world might be indefinitely postponed. New Year’s Day, however, though very cold, was quite calm and clear. We lashed our camping effects on the toboggan, donned our snowshoes and, by dint of hard, persistent toiling through the drifts, reached the scene of the caribou engagement shortly before noon.

There we were fortunate enough to meet the venerable Dorsey with his shaggy team ploughing through the snow.

“I’d have come,” he said, “if the snow had been up to their ears.”

The settlement was reached by the middle of the afternoon, and the following night saw us safely home after the longest and coldest drive over the Little River road, that I have ever experienced.

This article originally appeared in the January 1899 issue of Outing magazine.