At one time, controversy raged over who made the finest guns. Americans pointed to Parker, L. C. Smith, Fox, Ithaca, Lefever and late-to-the-party Winchester. British gentleman would talk James Purdey, Holland & Holland, Henry Atkin, Grant, Lang, Westley Richards and many others, some with more than a century of operation, as being the very finest. On the European continent we have Spain, Belgium, Germany, France, Italy and others. However, today let’s limit our discussion to American double guns and likewise those of the United Kingdom. As Sir Winston Churchill once said, “Two peoples separated by a common language.”

The “Golden Age” of side-by-side shotguns ran from about 1880 to the beginning of World War II. By that time, virtually all of the American gunmakers had gone bankrupt with some being bought by larger companies such as Fox’s purchase by Savage, Parker to Remington, etc. Ithaca was about the only one to continue uninterrupted, but that was completely due to its Model 37 pump gun and later a smattering of semi-autos. It, too, fell into bankruptcy, not once but twice, and is now back in business in Ohio sans the NID double.

The author with his A. H. Fox HE Grade Super Fox.

The Golden Age in England was known as the “Edwardian era,” so named after Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg, nicknamed “Bertie,” who became Edward VII upon the death of his mother, Queen Victoria. She thought of him as a bit of a bumbling oaf and gave him nothing to do, so shoot he did and lent his name to this great period of driven game shooting.

Lavish “shooting parties” were given with gargantuan banquets and with the expectation that the pheasant would be “shown” to require excellence in shooting technique so as not to “blot your copybook,” as the late Robert Churchill said. Churchill is known for his book Game Shooting that put in print and photos of Churchill, replete in argyle stockings and breeks, demonstrating correct shooting techniques.

Much of English landed gentry were driven into bankruptcy from throwing these shooting parties. If you’re interested, read Isabel Colgate’s novel The Shooting Party that was later made into James Mason’s last movie by the same title that illustrates the social manners and mores of a shooting party on the cusp of The Great War (WWI).

British-made and American-made doubles differ in several ways. British guns offered two styles of action, sidelock and boxlock. Americans—with the exception of L. C. Smith, whose guns were all sidelocks, albeit of very simple design compared with the seven-pin British guns—made boxlock guns. Which is better? Each has its attractions.

Sidelock guns perhaps offer better trigger pulls, but one major feature is the interrupting sear. If a gun is dropped or otherwise severely jarred, it can have its sear slip out of engagement with the hammer causing an accidental discharge, often with harmful or fatal consequences. Few boxlocks carry this feature but can offer trigger pulls equal to any sidelock. Speaking of triggers, many British-made double-trigger guns often have a hinged front trigger that saves wear and tear on the shooters trigger finger when firing the second barrel. Double triggers are never fired using two fingers, but rather the trigger finger shifts from front to rear or vice versa. Once, when guiding a goose hunter in Maryland, I had a young hunter put both of his fingers on the triggers and as he prematurely shoved the safety forward, he toggled his finger back, shooting a hole in the top of the pit!

Sidelocks are detachable with a proper turnscrew or screwdriver, although Holland & Holland’s guns feature “hand-detachable” sidelocks that, by means of the screw or “pin” attached to a lever on the side of the lock, is easily turned and the lock removed. After shooting in the rain or snow, being able to remove the locks to dry and relubricate them is a real advantage. On the other hand, boxlock guns are quite well sealed against water intrusion. Sidelocks do provide a broad palate for engraving, hence the development of side-plated boxlock guns that give the appearance of a sidelock but are just camouflage for a boxlock.

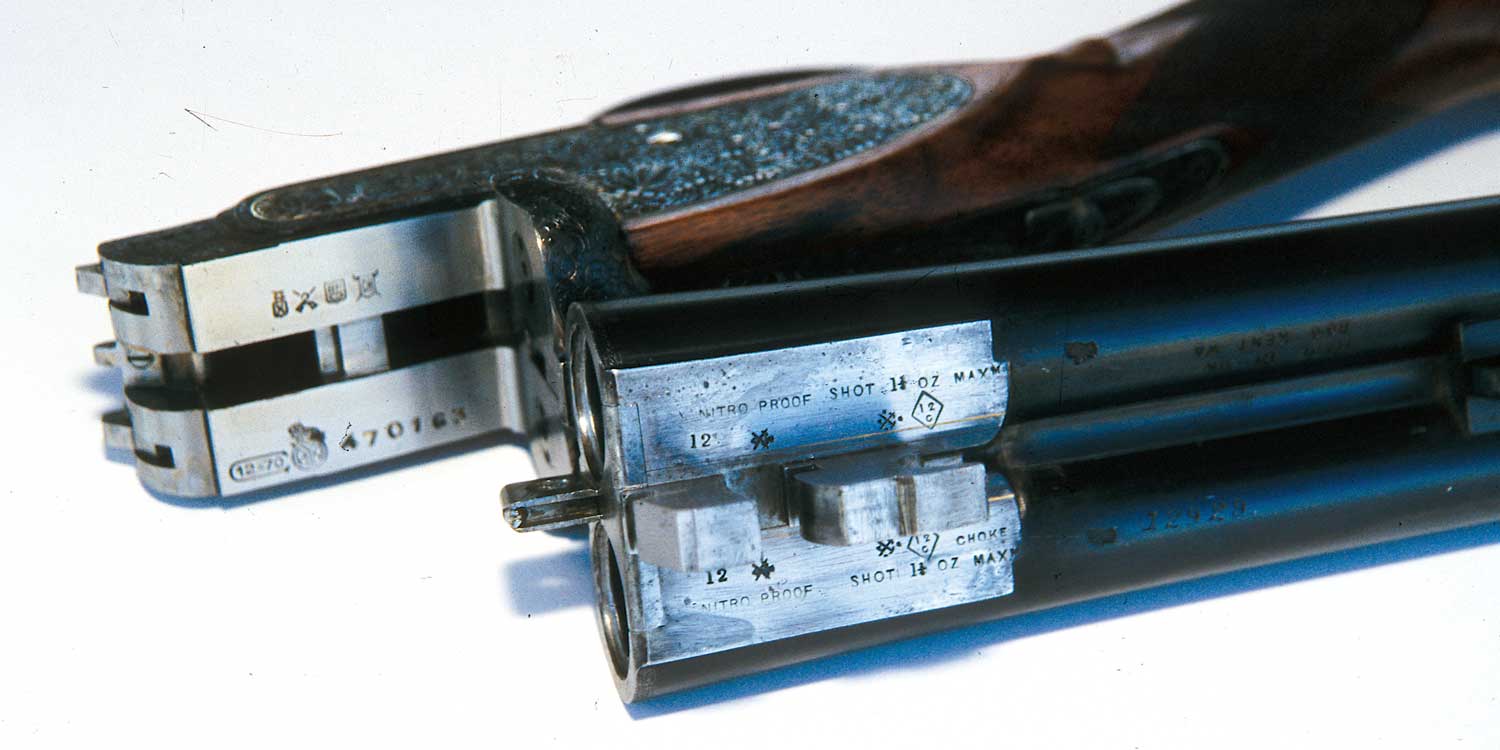

The London Proof House

British-made shotguns of this era tend to be more delicate in appearance and generally weigh in the 6-pound range. American guns are heavier, and this difference is easily seen in their intended uses. Historically, British shotshells are 2 1/2-inchs carrying in the vicinity of 1-ounce shot charges that are appropriate to driven pheasants and grouse on the moors. Often shooters would purchase their cartridges from the maker of their particular shotgun to ensure proper loads for their gun. Every gun made in the U.K. must be proofed at either the London or Birmingham proof house, where they were proofed for a particular dram weight of powder and a specific shot load. Vintage British gun cases will often contain a card with the cartridge information for that gun written on it.

Spanish (Eibar) proofed action and Birmingham, England reproofed barrels.

American guns were more robust and built to fill the pot. Consequently, the maker had no control over what ammunition the shooter used—so long as they fit the chamber, the choice of shell was up to the user. They might handload with a scoop of powder and a scoop of shot that could be old nails for all Parker Brother knew, so American guns are, in general, heavier. That’s not to say that the buyer couldn’t order a very light double for grouse in the alders or southern bobwhites. Every maker had a selection of actions and barrel weights to respond to individual orders. However, the majority of their production was of middle-of-the-road shotguns suitable for rough use when necessary.

Although American’s paid little heed to such, the British calculated the weight of the gun for its use. W.W. Greener, himself a gunmaker, offered the “Rule of 96” to guide makers to provide a gun that was pleasant to shoot over a long day of driven game. Or as one writer captioned a photo,“Lord So-and-So shooting himself into a shotgun headache.” If we multiply 96 by 1 (ounce) = 96 and divide by 16 (ounces in one pound) we arrive at 6 pounds, which is the best weight for shooting a 1-ounce load. It does not take into account velocity, which also has a direct bearing on recoil. Still, one finds that a great many fine British shotguns hover at this weight given the ammunition in common use when they were made.

I own a Henry Atkin (From Purdeys) that was made in 1895 and fits all the parameters of a London Best made for shooting driven birds. I know this because it is No. 2 of a pair; the whereabouts of No. 1 is a mystery. Henry Atkin apprenticed at James Purdey and worked in its shop for some years before going out on his own. When he engraved his guns with “From Purdeys,” Purdey immediately foamed at the mouth and sued Atkin. At the trial the judge asked, “Did you indeed work at Purdey’s?” To which Atkin truthfully answered, “Yes, Your Honor.” Followed by the judge’s statement, “Case dismissed!”

In those days, the building of shotguns in England was not quite what we perceive. It was, in fact, a cottage industry. Major components such as the action and the barrels were crafted in the company’s shop, but most of the rest was done by outside specialists. Shooting coach Chris Batha tells of his beginning involvement in the London gun trade by the route of being a London Fire Brigade member and having a ceiling fall on his head. Needing to wear glasses as a result of the concussion, he could no longer wear a protective mask and so, following retirement, began driving a London cab. Because he could park wherever he wished, he began ferrying gun parts to and from various specialists around London. Among the specialists were lock makers, stock makers, checkerers, case hardeners, etc. Some or all of these could be at the home works such as Holland & Holland, but it was an interesting fact of London and Birmingham gunmaking that many of the components of a bespoke shotgun were made by “outworkers.”

British gunmakers all worked their way through the apprentice system, and at its end were put to work at the skill for which they seemed best suited. The late Gough (pronounced Guff) Thomas who was the leading shotgun writer in England in the 1950s and ’60s mentioned that one of the final graduation exams for an apprentice was to file two blocks of steel so that they formed a “sucking fit” that made them stick together without aid of anything but real craftsmanship. Those skilled men and, now women, developed a feel for the steel and how their tools cut it that is pretty close to making gold from lead. True gunmaking started with a block of steel—probably a forging with the top tang, breechface and action flats roughly formed—that the actioner then filed, chiseled and drilled to make the action. Similar hand tasks were those of the stocker, lock or barrel maker, etc. London-Best guns had their barrels joined at the breech, then wedges were wired between them and they were then shot at the company’s shooting grounds and regulated to converge at whatever range was specified, usually 40 yards. They were then joined with top and bottom ribs, the choke regulated by additional trips to the shooting grounds, then the bore was lapped to mirror smoothness.

Holland & Holland’s work room.

There was a great scandal in British gunmaking circles when it was alleged that Spanish actions were being imported by some of the top gunsmakers for use in their bespoke guns. The Spaniards were known for fine top-quality copies of Holland & Hollands and others at bargain prices compared to those of a London gun. I have two AyAs that have served me very well for more than three decades. Sometime later, word leaked out that just perhaps the top gunmakers were using computers and CNC machines to craft their guns. As my late friend Michael McIntosh once said, “What difference is it if Michelangelo used a chisel and hammer or an air hammer to carve David;” the result is the same. Holland & Holland now proudly shows factory visitors its computer lab, but the finishing is all by hand.

Parker quality is exemplified in the inletting of the forend latch of a V-grade gun.

American-made shotguns were primarily built under one roof. Yes, some might checker or engrave outside of the company plant, but few were the outworkers. The real separating factor between American guns and British was that while British guns were hand-made from butt to muzzle, American guns were made of carefully machined then hand-fitted parts. One telling statement in a reproduction of the 1925-26 Winchester catalog states, “The parts for each model [repeater] are interchangeable, being made to gauge.” Being made to gauge is important because parts were made “to gauge” so they could be hand-fitted. It is from this being made to gauge that sprung the saying, “Close enough for government work,” which meant to gauge, but has morphed into less than complimentary usage. Actions were forged, milled, drilled and semi-finished, then put into a bin with other actions of the same size, weight, etc. Barrels were set in jigs, brazed together then fired during final inspection for impact, chokes were reamed then shot for percentage and altered as needed. When a gun was to be made for a customer or dealers’ stock, the worker went to the correct bin, removed an action and other parts from their respective bins and began fitting them. Common to both British and American’s top guns was that most kept complete records of for whom a particular gun was made, the date and other particulars. Nowadays, for a fee your gun can be researched, unless it’s like my Parker whose record book is missing so a date can only be estimated. One glance at the inletting of the forend iron of a Parker illustrates the quality of hand-fitting American-made guns enjoyed.

The author with a pair of Atlantic brant shot in Barnegat Bay with his 1924 Parker.

The appearance of the Winchester Model 21 in 1930 broke new ground. The water table, or action flats, are long, hence more bearing surface to absorb recoil. One of its salesmen, an active trap shooter, removed the Purdey-style sliding underbolt from his Model 21 only holding it closed with his hands as he shot. As a demonstration he would tie the barrels to the action with a string to prove the strength of the design. John Olin, the moving force behind the Model 21 (Who else would launch an expensive double during the Great Depression?) decided he wanted to show how tough a 21 really was, so a gun was taken from the warehouse and then subjected to shooting 2,000 proof loads that increase the pressure 50 to 60 percent over a gun’s service pressure, which is the maximum permitted pressure with proper ammunition. The Model 21 survived with nary a problem. Along with the 21, several other domestic and foreign guns were subjected to the test and all failed, most within the first 100 rounds. Failures were not in barrel bursts, but rather the actions being sprung so they could no longer be closed. That was obviously a severe test but showed the incredible toughness of the 21. Innovative in design, the barrels were dovetailed and pinned at the breech rather than being brazed, coil springs were used throughout and the single trigger worked fine, one of the bug-a-boos of most double guns.

My L. C. Smith Long Range has a Hunter-One single trigger that selects just fine so long as you want to shoot the left barrel first.

There’s nothing like owning and shooting a London Best knowing that vast amounts of highly skilled hand work went into its birth and was then handed to a gentleman to enjoy his day or days shooting high pheasant and now for me to use at an opening-day dove shoot. I can also shoot my A. H. Fox Super Fox at ducks on Mississippi’s historic Beaver Dam Lake, where Nash Buckingham shot his last duck, or geese on my lease in Maryland that brings a similar special thrill, so we’re really not as far apart as one would think.