When it comes to sharks vs. catfish, the cats win by a nose.

Hollywood has been in love with sharks for far too long. It is high time the catfish finally gets some glory.

Sure, sharks have an entire week devoted to them on the Discovery Channel, and then there is the Jaws movie series and the whole Sharknado disaster. But what about the hard-working, homely catfish? Just because he’s ugly he doesn’t deserve to be on TV? He doesn’t get to go for a ride in a tornado?

Sharks and catfish have a lot in common. Both fish species are deeply attracted to the scent of prey in the water and both act ferociously when they see food. But catfish are arguably much more fascinating as a whole.

Sharks and catfish have a lot in common. Both fish species are deeply attracted to the scent of prey in the water and both act ferociously when they see food. But catfish are arguably much more fascinating as a whole.

For centuries, the Chinese have used their sharp senses to predict earthquakes. Bullhead catfish in particular are so sensitive to low-frequency vibrations that they can detect rumblings in the earth’s crust days in advance and will greatly increase their activity before a quake, and in 1991 Japanese researchers spent $60K studying that phenomenon over 16 years. The channel catfish’s eyes are so sharp that its eyeballs are often used in medical research. As an added feat of prowess, one species of African catfish can even walk for short distances across land and breath air. I’d like to see Jaws do that.

The notion that sharks can sniff one drop of blood in a vast expanse of ocean is often overrated. True, some sharks detect blood at one part per million of water and can smell blood up to a quarter mile away. The lemon shark can detect tuna oil at one part per 25 million, while other species can detect their prey at one part per 10 billion, and some sharks can detect low concentrations of chemicals at up to several hundred meters.

But along comes the catfish and says, “Hold my beer.” When you hang out in a lot of dark and murky watering holes, and work a lot of late-night shifts, you need keen senses and the catfish’s senses of taste, smell, sight, touch and hearing are turbocharged. Catfish are basically covered from whiskers to tail with sensory organs that register everything from chemical and electrical data to vibrations and changes in water pressure.

“The ‘ampullae of Lorenzini’ are electroreceptors found around the snout/mouth area on sharks and, while these aid sharks in detecting food and feeding more efficiently, the mechanism itself functions differently than barbels found on catfish,” says Levi Kaczka, a biologist and fisheries coordinator with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources. “Much of the catfish’s senses in terms of feeding efficiency come by way of their ‘whiskers,’ correctly known as barbels. Most catfish we have in South Carolina inhabit the darker, deeper, portions of the water column. When compared with other predatory species (e.g., largemouth bass, striped bass, pickerel) you’ll notice a much smaller eye, even in flathead or blue catfish that can reach weights pushing 100 pounds or more. This is because feeding success relies mainly on using their barbels, rather than vision.”

Catfish can detect chemical signals at lower concentrations than any other vertebrate. They can detect less than one amino acid molecule in a trillion molecules of water. Their nostrils can detect some compounds at one part per 10 billion parts of water. Catfish senses are so acute, they can tell where a bait fish has been through pressure changes left in their underwater wake and follow that trail to food.

Catfish can detect chemical signals at lower concentrations than any other vertebrate. They can detect less than one amino acid molecule in a trillion molecules of water. Their nostrils can detect some compounds at one part per 10 billion parts of water. Catfish senses are so acute, they can tell where a bait fish has been through pressure changes left in their underwater wake and follow that trail to food.

Of all the catfish’s super senses, however, two stand out: taste and electrosensing. In addition to taste buds in the mouth and whiskers, the entire surface of their smooth, scaleless skin is covered with taste buds – it’s basically a living, swimming tongue! A catfish only six inches long has more than a quarter million taste buds on its skin. On adult fish, there are at least 5,000 taste buds per square centimeter of skin. Fishermen beware: if you ever wondered why the catfish didn’t bite, it is probably because you touched the bait with something distasteful on your hands such as gasoline, sunscreen, insect repellant or tobacco.

Perhaps their most amazing superpower is electrosensing, a “sixth sense” they share with sharks. Electroreceptive pits along the lateral line detect electrical fields in living organisms at very minute levels, which is the equivalent of detecting a flashlight battery at several thousand yards.

If having a super sniffer, wall-to-wall taste buds and built-in electronics doesn’t convince you that the catfish deserves some love, consider these final facts. With more than 2,200 species, catfish are among the most diverse group of fishes on earth and can be found on every continent except Antarctica. From recreational fishing to commercial and farm-to-table industries, the humble catfish arguably accounts for more of an economic impact than any freshwater cousin, which means that while some species of shark are eating tourists, the catfish is bringing them to town.

From a culinary standpoint, most catfish species are fine dining, but only certain shark species are really edible. From an angler’s standpoint, most would argue that a catfish puts up a stronger, more sporting fight than a shark of similar size or larger.

Who knows, maybe if folks show enough love and appreciation to the catfish, we can finally get an official “Catfish Week” on TV. Perhaps Sporting Classics with Chris Dorsey?

Sources

Fishing For Catfish, Keith Sutton, Creative Publishing International, 1998.

Making Sense of Catfish Senses, Dr. Hal Schramm, In-Fisherman magazine, 2018.

Catfish Are Off the Hook After Tokyo Ends 16-Year Earthquake Prediction Study, David Thurber, The Associated Press, April 26, 1992.

Shark & Ray Myths, The American Museum of Natural History, 2001.

Catfish photos by Michael Dewitt, Jr. and former SCW editor David Lucas, SCDNR. Shark photos courtesy of Erin Weeks, SCDNR.

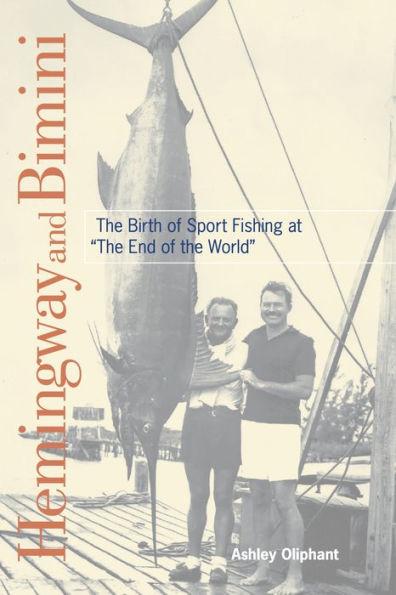

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his underappreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

This is the only book on this period in Hemingway’s life and reveals unexpected dimensions to the Hemingway portrait that deserve attention, including his surprising humor, his advanced conservationist views several decades before the environmental movement even began, and his egalitarian ideas about his contemporary female counterparts in the big-game fishing world—challenging the usual portrait of Hemingway as a chauvinist with no personal rules, boundaries, or conscience. Includes beautiful vintage photographs of 1930s Bimini that have never been published in book form. Buy Now