Before he bounced from the grass, I’d figured deer would be deeper in the hills. That was a useful assumption, Dunderhead. Odds of turning up that buck again were low; but without effort they were zero.

A furlong or two down a contorted wash, I hooked toward where the buck had gone and climbed a knob. Cresting on my belly, I glassed the opposite grades in layers, from the top, as they rose into the binocular. The antler tip was white. My sling came taut as I brought scope to eye. Below the tine, a sliver of solid dun winked through nodding fescue. At the report the deer lunged from its bed, then buckled and rolled down the slope, dead. I pocketed the hull, slid another cartridge into the single-shot.

Repeating rifles that functioned reliably are little older than automobiles. For centuries, hunters grew up on single-shots. Pilgrims to the New World landed with “working guns” of the day: smoothbore muskets typically 75-caliber and six feet long. Smaller, rifled bores followed, conserving precious lead and increasing accuracy. The elegant “Kentucky” rifle gave way to the utilitarian “Tennessee” or “Mountain” rifle.

Two centuries after the landing at Plymouth Rock, frontier’s hem lay beyond the Mississippi. W. H. Ashley, head of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, came up with the “Rendezvous” to collect furs from the West. Tons of pelts funneled annually from remote outposts to St. Louis. Easterners seeking fortune there included Jacob Hawken, from a family of gunsmiths in the East. In 1822 his brother Samuel closed a gun shop in Xenia, Ohio to join him. By 1825 the two were partners in a business to build rifles for frontiersmen. The archetypal Hawken scaled about 10 pounds. It had double-set triggers, a half-stock with no patchbox, a 38-inch, 50-caliber octagon barrel of soft iron. Slow-twist Hawken bores fouled less readily than did harder, quick-twist barrels of “more modern” rifles. Until 1840 Hawkens had flint locks.

When the California Gold Rush began in 1849, a Hawken rifle cost about $22.50. That year Jake Hawken died of cholera. Sam, who lived until age 92, hired German immigrant J.P. Gemmer to help in the shop. Gemmer bought the business in 1862 and kept it open until 1915. He died four years later.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, European explorers were killing Africa’s biggest game with single-shot front-loaders. One evening in the 1840s, R. Gordon Cumming was making hard bullets “…using [one part] pewter to four of lead…when we heard a troop of elephants splashing…. I resolved that night to watch the water [so] ordered the usual watching-hole…. I had lain about two hours in the hole when I heard a low rumbling [from] the bowels of the elephants…. They approached with so quiet a step that I fancied it was the footsteps of jackals…. I then peeped from my sconce with a beating heart, and beheld two enormous bull elephants, which looked like two great castles, standing before me. I could not see very distinctly, for there was only star-light. Having lain on my breast some time taking my aim, I let fly at one of the elephants, using the Dutch rifle carrying six to the pound.”

Firing a 6-gauge muzzleloader at an elephant towering over him in the dark, Cumming knew his first shot was also his last. In this case the beast ran off. Not all elephants did. On a daylight hunt soon after, he stalked to “within twenty yards, and fired at the side of the head of the elephant that stood next to me…. [Then] my back was to them, and I was running for the outside of the cover at my utmost speed.”

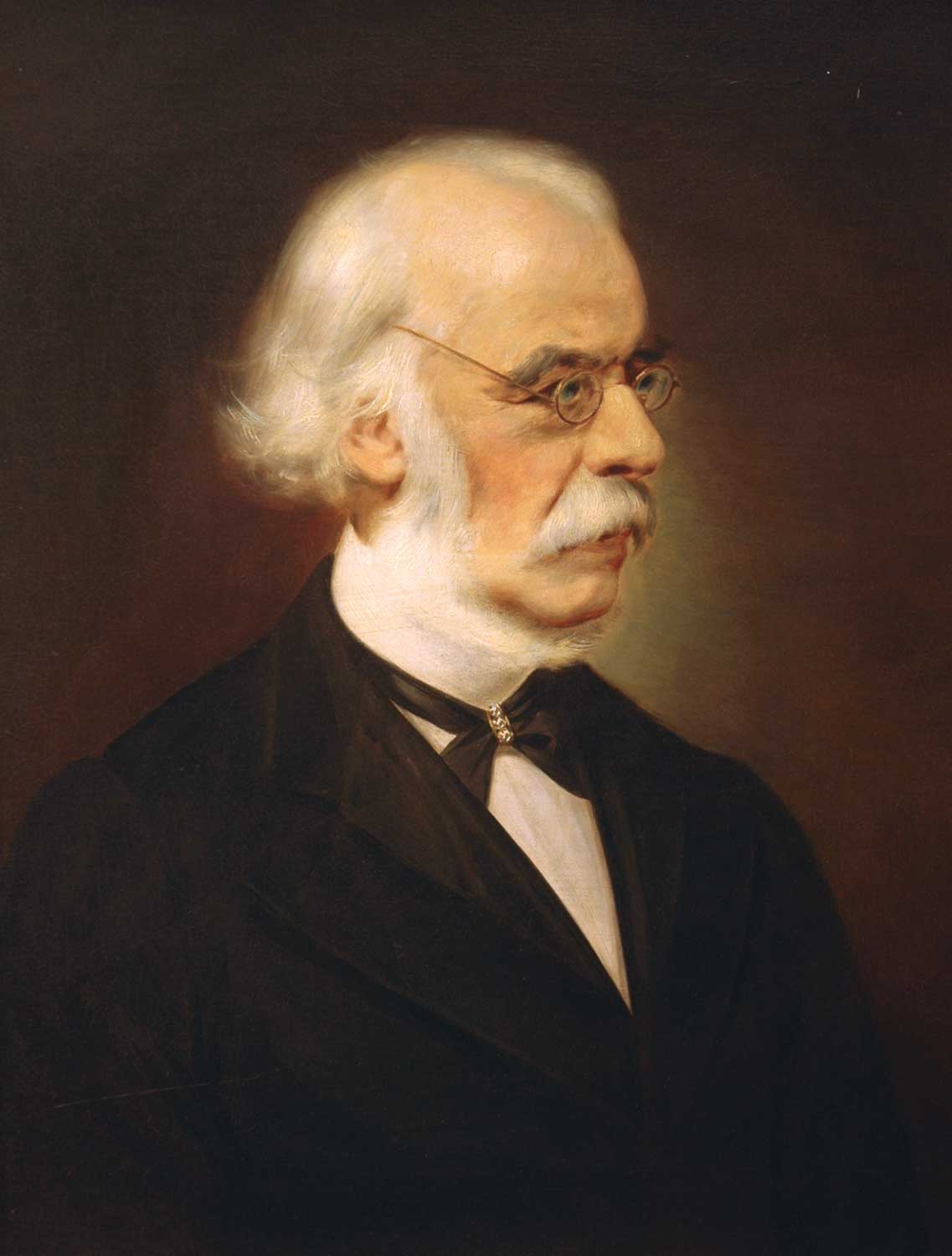

Tobacconist Harris Holland and nephew Henry launched their gun business in 1837, profiting from the endorsement of Sir Samuel Baker who in 1869 ordered a 3-bore single-shot from Holland & Holland.

Striking a massive blow with the first ball made sense. In 1840, when Samuel Baker was 19 years old, he ordered a 4-bore rifle from Bristol gunmaker George Gibbs. It finished out at 21 pounds and burned 16 drams (437 grains) blackpowder to thrust a 4-ounce (1,750-grain) silk-patched bullet through a two-groove, 36-inch barrel. Baker’s exploits helped tobacconist Harris Holland and his nephew Henry grow their gun business, founded in 1837. In 1869 Holland & Holland built Baker a 3-bore that hurled a 5-ounce (2,187-grain) bullet. Baker died in 1893, age 72.

In the middle 1800s, breech-loading cartridges inspired lightweight double rifles that, with their faster bullets, hit harder than big-bore muzzleloaders. English gunmaker James Purdey announced .450 and .500 Black Powder Express rifles in 1856.

Double rifles were expensive, however, and unnecessarily powerful stateside, where inventors turned to repeating mechanisms. The Civil War had tainted the future of front-loaders. Of 27,574 guns gathered after battle, noted one report, “at least 24,000 [were] loaded; about one half of these contained two loads each, one fourth from three to ten loads each…. In some, the balls [lay] at the bottom of the bore with the charges (sic) of powder on top…. Twenty-three loads were found in one Springfield rifle-musket.”

The 1873 Trapdoor Springfield in 45-70 served the U.S. Army nearly 20 years as its last single-shot.

Oliver Winchester’s Henry repeater got its first blooding in that conflict. But the 44 Henry rimfire was an anemic cartridge. Buffalo hunters traded their Hawkens for breech-loaders reluctantly, and then mainly for single-shot Sharps falling-blocks and Remington Rolling Blocks. The U.S. Army would issue 1873 Trapdoor Springfields for 20 years before adopting a repeater.

Young New Jersey gunsmith Christian Sharps apprenticed under John H. Hall, who’d patented a breech-loading rifle in 1811. Setting out on his own, Sharps secured an 1848 patent for a vertically sliding breech-block operated by an under-lever. In 1849, as Walter Hunt developed the Volitional Repeater that sired the Henry, Sharps wrangled a $500 loan. Incorporated in 1851, the Sharps Rifle Manufacturing Co. contracted with Robbins & Lawrence, then largest of U.S. firearms manufacturers, to produce rifles. Just before R&L went defunct in 1856, Christian Sharps left to found C. Sharps & Co. Tuberculosis claimed him at age 63 in 1874. C. Sharps & Co. soon shuttered. Sharps Rifle Mfg. Co. produced rifles until 1881.

The New Model 1869 was the first Sharps in metallic chamberings, preceding the 1870 debut of the New Model 1874. The ’74 Sharps lasted 12 years at the height of the market-hunting era. Its powerful .50 used 100 grains of blackpowder to send 473-grain paper-patched bullets. Proprietary Sharps ammo, however, was hard to get. Indians left Sharps rifles with dead settlers and hunters, but eagerly snatched up Winchesters and Springfields, as 44-40 and 45-70 cartridges were everywhere.

Changing times drew the curtain on Sharps hunting rifles. By 1880 so many bison had been killed that three million tons of bones would be scavenged from the fly-blown plains.

Diminished herds also depressed sales of Remington’s Rolling Block. Rushed into production in 1866 to replace military orders after Appomattox, this single-shot soon proved itself afield. Quick to load (Remington claimed a practiced shooter could send 20 bullets a minute), it was strong, too. One Rolling Block was proofed with 40 balls and 750 grains of powder, the charge consuming 36 inches of its 40-inch barrel! Upon firing, “nothing extraordinary occurred.” Winchester’s lever-action 1873 couldn’t match the Rolling Block on buffalo hunts, where accuracy and power mattered most. “Brazos” Bob McRae claimed 54 buffalo with as many shots at one stand with a Malcolm-scoped Remington in 44-90! In 1873 George Custer reported: “With your [Rolling Block] rifle I killed far more game than any other single party…at longer range.” Available in myriad chamberings, the Rolling Block would be produced until 1933.

These single-shots also excelled in competition. At Long Island’s Creed’s Farm in 1874, Sharps and Remington target rifles helped American marksmen beat the Irish champs. Each shooter of six-man teams fired at 800, 900 and 1,000 yards. In the decade that claimed Wild Bill Hickok, a scoped 22-pound Sharps match rifle in 44-90 fetched $118! A comparable Remington, by L.L. Hepburn, brought as much.

Ballard single-shots, here a 45-70, were once very popular in the U.S. for hunting and target shooting.

Meanwhile, in Ogden, Utah, firearms prodigy John M. Browning invented a single-shot rifle. He filed his first patent request in 1879. Then he and his four brothers built a small factory to produce rifles. In 1883, Winchester VP Thomas G. Bennett was shown a second-hand Browning. He traveled six days by rail from New Haven to buy all rights. John wanted $10,000—an enormous sum. Bennett clinched a deal at $8,000, adding to Winchester’s repeating-rifle line a more potent hunting rifle. Browning’s single-shot would become Winchester’s Model 1885, and outlast the era’s Ballard, Maynard and Stevens rifles.

The industrial revolution and metallic cartridges affected rifle design world-wide. In 1872 John Farquharson of Daldhu, Scotland, patented a dropping-block single-shot. He sold part interest to George Gibbs, who produced the rifle until the patent expired in 1889. Gibbs built fewer than 1,000 Farquharsons before the last shipped in 1910. By then the mechanism had a following. Auguste Francotte of Herstal, Belgium, copied the action. British gunmaker W.J. Jeffery & Co. adopted it as early as 1895 and in 1904 introduced an oversize variant for the 600 Nitro Express. Post-Gibbs Farquharsons bore a “PD” stamp, indicating the design had become “public domain.”

On mainland Europe, elegant single-shot rifles had long issued from Austria’s gun-making center, Ferlach. Its first gunsmith of record appeared in 1551 registries of the Hollenburg Estates, which would furnish Slovenia’s Ljubljana Armory with 400 arquebuses. By 1732 area gunmakers were sending rifles to the Austrian Army. Sporting rifles followed. One family still building rifles in Ferlach, opened shop in 1790. Fanzoj (Fanzoy) specializes in kipplaufs, traditional hinged-breech single-shot “stalking” rifles.

“Into the 1960s Ferlach had 56 gun-making shops,” said Daniela Fanzoj who, with brother Patrick runs the family business. “Now there are five.” Handwork comprises about 70 percent of the investment in each Fanzoj rifle. “Our 10 employees are skilled craftsmen, building firearms from scratch—now with assistance from five-axis CNC and wire EDM machines.”

Lithe and lightweight, “the kipplauf reflects our sporting culture,” explained Patrick. “The hunt is best completed with a one-shot kill from an elegant rifle.”

Early kipplaufs were chambered for cartridges such as the 8x50R Austrian Mannlicher, circa 1888. The Great War vetted rimless rounds, but Britain’s .303 and rimmed versions of Old World favorites—6.5x57R, 7x57R, 7x65R—endure. Post-WW I sanctions on German military cartridges added the 8x60R.

“You must try my 6.5x57R,” Patrick insisted. Rifle fire echoes over Ferlach daily—the sound of tradition very much alive. In a clubhouse dating to 1906, I sandbagged the kipplauf on a window bench that had steadied rifles for more than a century. The trigger broke like a thin icicle. Three shots drilled a nickel-size knot in target’s center. “No need for three,” smiled Patrick. “Kipplaufs kill with the first.”

John Browning designed the single-shot Winchester bought and later produced as its Model 1885, here.

A Fanzoj kipplauf might strain your budget. Ditto a vintage Farquharson. Sharps “buffalo rifles” have been ably resurrected by Shiloh Sharps in Montana. Browning revived the Winchester 1885 in 1973 as the affordable but well-made Model B-78, then again in 1985 as the Model 1885. My Lyman Ideal 38-55 is a svelte, finely fitted “Baby Sharps.” Dakota made one, too, and crafted beautiful rifles on the bigger, modern Miller action. The Ferrari of American single-shots? In my view it’s Don Allen’s Dakota Model 10. I dug deep for one, a 280 Remington with NECG sights and warm English walnut. But to many hunters stateside, “single-shot” conjures up Ruger’s No. 1, a Farquharson-inspired rifle with a trimmer profile. Ace stocker Lenard Brownell shaped the No. 1’s stock to fit nearly everyone, right- or left-handed. Its straight comb aligns my eye behind the iron sights of “A,” “H,” “S” and “RSI” versions of the rifle, and behind scopes in the medium rings furnished for quarter-rib bases on these and sight-free No. 1 “B” and “V” variants. Grip cap and thin rubber pad hew to English tradition. Point-pattern checkering is fetching and functional.

The No. 1’s breech-block moves like greased glass. The trigger adjusts. So, too, the extractor—for smart ejection or to nudge hulls free for plucking. While dropping-block actions excel with rimmed cases, Bill Ruger designed the No. 1 to function reliably with rimless. The tang safety is unobtrusive but easy to thumb. The compact breech is about four inches shorter than a bolt rifle’s receiver. So you get higher bullet speeds than with a bolt-action for any given rifle overall length. Handloaded 180-grain Nosler Partitions exit the 26-inch barrel of my No. 1B in 300 Winchester at 3,040 fps, factory-loaded Power-Points at 3,006. In a 24-inch-barreled bolt rifle, the same loads clock 2,985 and 2,945.

Ruger’s No. 1 welcomes a range of cartridges, brooks high pressures, requires hand fitting and timing.

Bill Ruger announced this rifle in 1966 at a list price of $265. Chamberings grew to include, at this writing, 54 from 22 Hornet to 416 Rigby. My first No. 1 was a 7×57. I’ve managed to gather in a few others, some with the lovely walnut. Wood quality has fallen of late as supplies of figured walnut have dried up. Ruger has pruned the No. 1 line, too. Excluding distributor specials, just one version, in a single chambering, is cataloged each year, to be discontinued the next. The No. 1 now retails for $1,899.

At Ruger’s factory, where one of the company’s popular 10/22 rifles can pop off the production line every 30 seconds, the No. 1 cell is tiny. At my last visit, two technicians were fitting and assembling rifles on padded tables. One was timing the close of a No. 1 lever while his colleague mated a buttstock to a tang. I came away wondering how Ruger could once have sold these hand-built rifles for $265.

The No. 1 has served me well afield. I favor the agile “A” and longer “S” versions, with their iron sights and British stalking-rifle profiles. In Oregon’s high country, they’ve taken fine bucks. A 7×57 also tumbled an impala sprinting through Zimbabwean thorn at mere feet.

This 100-yard iron-sight knot owes much to good fortune. The rifle has also blessed van Zwoll with game.

In the rugged brakes above Idaho’s Salmon River, we’d seen no elk for most of a week. When we spied the herd, Ken pressed upon me his Ruger No. 1 barreled to a short 7mm magnum. “You might need it.” Above my protests, he snatched my iron-sighted 71 Winchester in 450 Alaskan. The elk were half a mile off, moving steadily off the ridge. “Best run,” he added. A scramble down-slope, then through scrub pines and boulders on spine’s edge halved the distance. But most of the herd had already filed into dark timber; only a few cows and the bull remained in the cemetery of charred lodgepoles on top.

No time left.

I slinged up and reeled in a few more yards on my belly. Breathing hard, I locked my lungs and settled the crosswire on a slot 300 yards away. Charitably, the bull paused there. My 140-grain AccuBond punched his front ribs. I dropped the lever, yanked another round from my pocket, fired again. Another “thwuck.” Fatally stricken, he collapsed as the 7mm barked once more.

A single-shot rewards care with the first shot but doesn’t absolve you of follow-ups.

This prairie whitetail dropped to a 180-yard shot from van Zwoll’s full-stocked No. 1RSI in 303 British.

Ken’s quick generosity had given me that six-point. No one could have been more pleased than I when, the last morning of our hunt, he killed a bull at 380 steps with that Ruger No. 1.

As with repeating rifles, the best-remembered single-shots are those that bring you to fine country with good company and acquit themselves well against worthy game. Hanging your fortunes on “just one bullet up the spout” simply makes those final seconds sweeter.

This article originally appeared in the 2022 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.