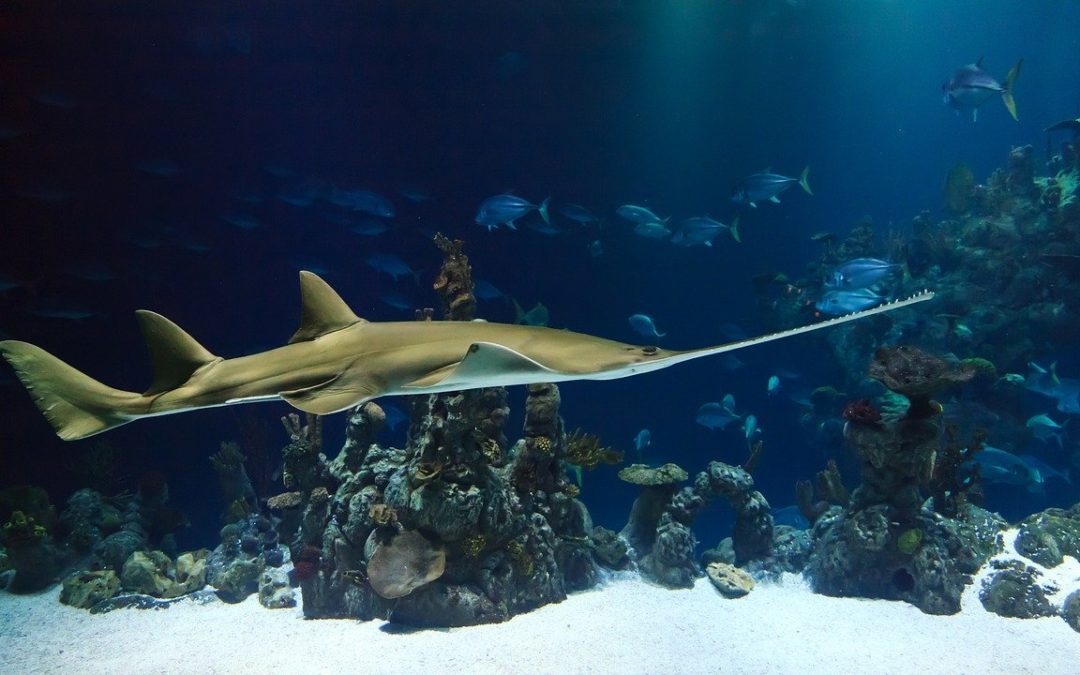

When I started graduate school at Florida State University, I had never seen a sawfish in the wild, but I was excited to be part of the recovery of a species I had been so awestruck by in aquariums.

The smalltooth sawfish, the only sawfish found in Florida, has been protected in Florida since 1992 and became federally listed under the U.S. Endangered Species Act in 2003. Little was known about the species when it became listed, but since that time, scientists have learned a lot about its biology and ecology.

As sawfish recovery efforts continue, we expect there to be more sawfish sightings, especially in Florida, and that includes anglers who may accidentally catch one on hook-and-line while fishing for other species.

Sawfish Encounters

Sawfish can be encountered when participating in a number of activities including boating, diving and fishing. The species may also be encountered by waterfront homeowners and beach goers in the southern half of the state where juvenile sawfish rely on shallow, nearshore environments as nursery habitats.

When fishing, targeting sawfish is prohibited under the ESA, though incidental captures do occur while fishing for other species. Knowing how to properly handle a hooked sawfish is imperative, as sawfish can be potentially hazardous to you.

One of the first things that stood out to me while conducting permitted research was the speed at which a sawfish can swing its rostrum (commonly referred to as the saw). For creatures that glide along the bottom so slowly and gracefully, they sure can make quick movements when they want to. It’s best to keep a safe distance between you and the saw.

If you happen to catch a sawfish while fishing, do not pull it out of the water and do not try to handle it. Refrain from using ropes or restraining the animal in any way, and never remove the saw. It is important that you untangle it if necessary and release the sawfish as quickly as possible by cutting the line as close to the hook as you can. Proper release techniques ensure a high post-release survival of sawfish.

Scientific studies show us that following these guidelines limits the amount of stress a sawfish experiences as a result of capture. Note that a recent change in shark fishing rules requires use of circle hooks, which results in better hook sets, minimizes gut hooking and also maximizes post-release survival.

In addition to capture on hook-and-line, sawfish are easily entangled in lost fishing gear or nets. If you observe an injured or entangled sawfish, be sure to report it immediately, but do not approach the sawfish. Seeing a sawfish up close is an exciting experience, but you must remember that it is an endangered species with strict protections.

If you are diving and see a sawfish, observe at a distance. Do not approach or harass them. It is illegal and this guidance is for your safety as well as theirs.

An important component of any sawfish encounter is sharing that information with scientists. Your encounter reports help managers track the population status of the species. If you encounter a sawfish while diving, fishing or boating, please report the encounter. Take a quick photo if possible (with the sawfish still in the water and from a safe distance), estimate its length including the saw and note the location of the encounter. The more details you can give scientists, the better they will understand how sawfish are using Florida waters and the better they can understand the recovery of the population. Submit reports at SawfishRecovery.org, email sawfish@MyFWC.com or phone at (844) 4SAWFISH.

Sawfish Background

Sawfishes, of which there are five species in the world, are named for their long, toothed “saw,” or rostrum, that they use for hunting prey and defense. In the U.S., the smalltooth sawfish was once found regularly from North Carolina to Texas, but its range is now mostly limited to Florida waters.

In general, sawfish populations declined for a variety of reasons. The primary reason for decline is that they were frequently caught accidentally in commercial fisheries that used gill nets and trawls. Additional contributing factors include recreational fisheries and habitat loss. As industrialization and urbanization changed coastlines, the mangroves that most sawfishes used as nursery habitat also became less accessible. For a species that grows slowly and has a low reproduction rate, the combination of these threats proved to be too much.

Engaging in Sawfish Recovery

During my thesis research, which focuses on tracking the movements of large juvenile and adult smalltooth sawfish, each tagging encounter is a surreal experience.

The first sawfish I saw was an adult, and what struck me the most was just how big it was. I also remember being enamored by its mouth. Like all other rays, its mouth is on the underside of its body. The mouth looks like a shy smile and I found it almost humorous how different the top of the sawfish was compared to the bottom. After seeing my first baby sawfish, the contrast seemed even greater. It’s hard to believe upon seeing a 2- to 3-foot sawfish that it could one day be 16 feet long! No matter the size, anyone who has encountered a sawfish will tell you it’s an experience like no other.

The hope is that one day the sawfish population will be thriving once again, and more people will be able to experience safe and memorable encounters with these incredible animals. Hopefully, we can coexist with sawfish in a sustainable and positive way in the future.

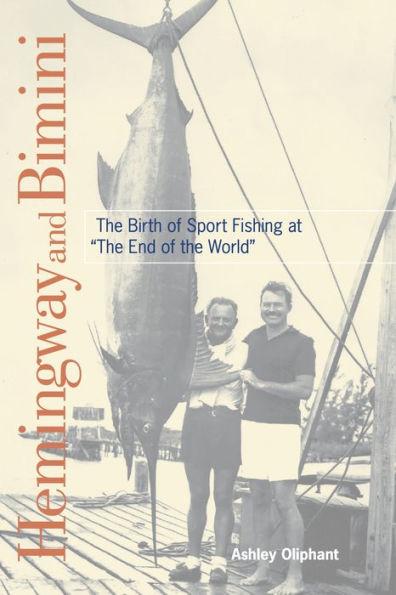

Follow Ernest Hemingway’s exploits on the Bahamian island of Bimini from 1935 to 1937, the very moment in time when the International Game Fish Association (under the author’s co-leadership) was emerging. Covers Hemingway’s role in the formation of the IGFA, his under appreciated seminal writing about competitive saltwater angling when the sport was still in its infancy, the amazing fishing he enjoyed on the island, and the way all of these experiences translated into the composition of his posthumous novel Islands in the Stream.

This is the only book on this period in Hemingway’s life and reveals unexpected dimensions to the Hemingway portrait that deserve attention, including his surprising humor, his advanced conservationist views several decades before the environmental movement even began, and his egalitarian ideas about his contemporary female counterparts in the big-game fishing world—challenging the usual portrait of Hemingway as a chauvinist with no personal rules, boundaries, or conscience. Includes beautiful vintage photographs of 1930s Bimini that have never been published in book form. Buy Now