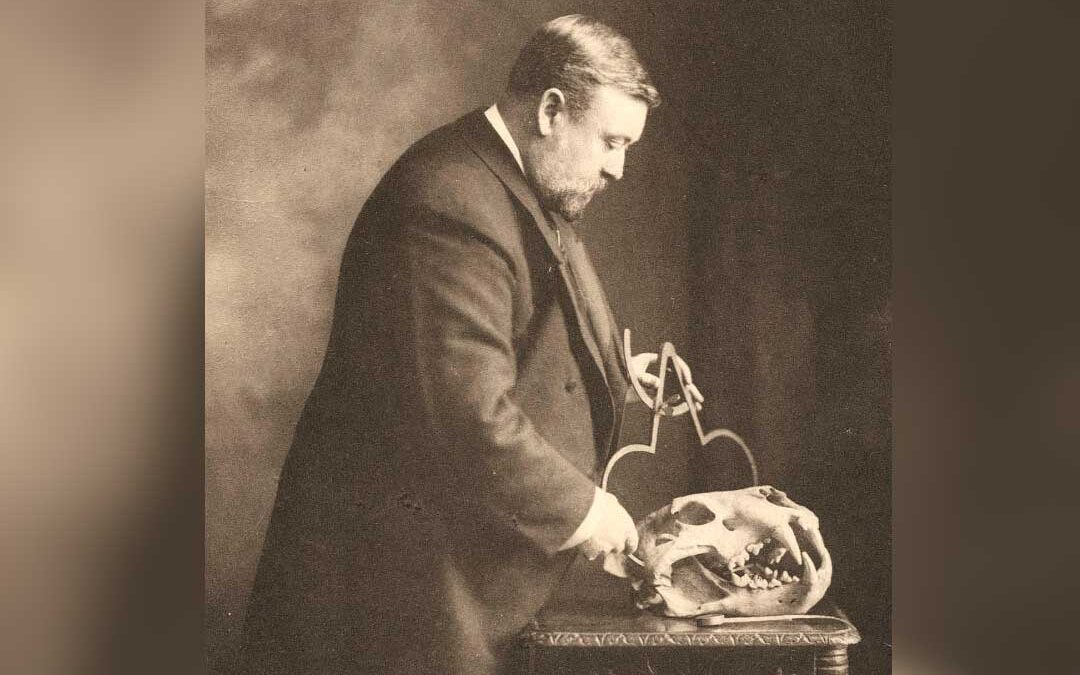

Although the average big-game hunter may know little if anything about the life of an individual who was a man for all seasons in the world of Victorian and Edwardian sport, Rowland Ward, virtually everyone is aware of the long-running series of record books bearing his name. Those volumes, now spanning well over a century of publication and totaling some 30 editions, offer for game animals of the world what Boone & Crockett record books provide for those native to North America. Yet these massive sporting reference works give, at best, but a hint of the life of a fascinating individual who was at the center of the world of big-game hunting in what must be reckoned its heyday.

James Rowland Ward was born in London in 1847, and his sire, Henry Ward, was one of the leading British taxidermists of the mid-Victorian era. A keen student of nature, the senior Ward was a close friend of John James Audubon and accompanied the famed artist/naturalist on a number of his travels in search of new species. Many years later, well into adulthood and already a major figure on the British sporting scene, son Rowland would take great delight in traveling to the United States and tracing some of his father’s footsteps.

The Ward family, as a whole, was greatly enamored of hunting, fishing and natural history. Both Rowland’s brother, Edwin, and his nephew, Herbert Ward, would establish solid reputations in fields linked to taxidermy. Edwin became a talented animal artist as well as an accomplished taxidermist, while Herbert Ward made quite a name for himself as an African traveler. He was a part of the final expedition to the Dark Continent by famed explorer Henry Morton Stanley; subsequently demonstrated exceptional aptitude at depicting the savage beauty of Africa in wildlife sculpture; and made significant literary contributions with works such as My Life with Stanley’s Rear Guard, Five Years with the Congo Cannibals and A Voice from the Congo.

As for Rowland, he clearly was, to take words from his autobiography, A Naturalist’s Life Study in the Art of Taxidermy, “born into the business.” He abandoned formal education rather early at the age of 14 and joined his father in the family business. At that juncture the enterprise was small, struggling and seemingly had anything but a promising future. Young Rowland, though barely in his teens, set out to change that in the energetic fashion that would characterize his entire life. Through dint of hard work, dogged determination and considerable talent, “The Jungle,” as the premises he would eventually acquire in London’s fashionable Piccadilly district came to be known, became the calling place for affluent sportsmen with ample leisure to rub elbows with one another.

As for Rowland, he clearly was, to take words from his autobiography, A Naturalist’s Life Study in the Art of Taxidermy, “born into the business.” He abandoned formal education rather early at the age of 14 and joined his father in the family business. At that juncture the enterprise was small, struggling and seemingly had anything but a promising future. Young Rowland, though barely in his teens, set out to change that in the energetic fashion that would characterize his entire life. Through dint of hard work, dogged determination and considerable talent, “The Jungle,” as the premises he would eventually acquire in London’s fashionable Piccadilly district came to be known, became the calling place for affluent sportsmen with ample leisure to rub elbows with one another.

While those heady times of fortune and fame lay far in the future, from the outset Rowland displayed a rare capacity for arduous endeavor. Rarer still, he combined an artist’s abilities with a shrewd businessman’s temperament. In due course his workaholic ways paid meaningful dividends from the central focus of his business, but it was likely his creativity and ability to recognize ways in which he might broaden the business that underlay his rise to international prominence. Along with providing excellent taxidermy services, Ward developed a keen sense of the sort of novelties and tchotchkes likely to appeal to his sporting consumers. He was able to do so in a fashion that resulted in major inroads into the decidedly staid, hide-bound nature of British outdoorsmen of the late Victorian and Edwardian eras. Following the death of his father in 1878, Rowland ventured out in all sorts of new and noteworthy directions. Over time he would introduce scores of noteworthy new products, launch a publishing business that included maintenance of big-game record books, offer a sort of advisory service for peripatetic sportsmen and help facilitate international travel to hunt and fish.

While he was responsible for numerous innovations, including what he termed an “aquatic novelty” in the form of a motorized canoe, there were two distinct areas directly related to taxidermy where he made his greatest impact. Those involved major exhibitions of sporting history and creation of a wide variety of decorative or novelty items fashioned from inedible portions of birds and animals. Late in 1879, a year after his father’s death and with an impressive number of taxidermy awards already to his credit, he arranged an immensely popular exhibition focusing on the fearsome Zulu warriors of southern Africa. The catastrophic Zulu War in the first half of that year, with the tragic massacre of British soldiers in battles at Rorke’s Drift and Isandlwana, was all too fresh in British minds. Ward’s display, utilizing native weapons including fearsome assegais, cowhide shields, clothing and other accoutrements of Zulu warriors, proved a striking success. It would be the first in an ongoing series of such exhibits serving multiple purposes such as providing publicity, drawing fee-paying crowds to his Piccadilly premises and beating the imperial drum.

For the next three decades, a visit to his premises became almost a mandatory part of any full London sightseeing tour, and visiting sportsmen with deep pockets flocked to the establishment to spend serious money even as the curious masses enjoyed the exhibitions. The exhibits were always mounted with meticulous attention to detail, changed frequently and were, in effect, the forerunners of the panoramic displays found in today’s natural history museums.

A late Victorian antelope horn and oak occasional table made and retailed by Rowland Ward and a Victorian brass firescreen mount of the tail of a male superb lyrebird by William Plowman of Rowland Ward.

Alongside the mounts featured in Ward’s displays were offerings of numerous knickknacks fashioned from bones, hooves, feathers, skins and other animal parts. He was able to engender fashion trends for both men and women, and a specific style of indoor decoration the man inspired came to be known as Wardian furniture. From feather hats and muffs to women’s jewelry, from antlers used in ingenious ways to “everything elephant,” this ingenious entrepreneur figured out a way to delve deeply into the pound-laden purses and billfolds of the British elite. His work with elephants offers perhaps the finest example of Ward’s genius and versatility. He developed a special process for treating elephant hides and, from those skins, fashioned striking amulets, bracelets, tabletops, footstools, drink trays, pendants, ink wells and much more. Elephant feet became functional liqueur stands and, even today, his elephant foot umbrella holders occasionally appear in upscale antique shops and as auction offerings. Decades ago, while wandering London’s famed Portobello Road market, this writer saw one dealer whose wares focused exclusively on such items.

Another savvy move by Ward was to handle what he rather quaintly described as “the setting up of defunct pets.” Modern sportsmen often bury a treasured hunting dog and mark the site with an engraved stone, but he upped the ante appreciably by mounting deceased canine companions for display, usually in a realistic pose, in gun rooms. Similarly, women could have their treasured poodle or pug mounted and placed in the parlor. This might seem strange or even ghoulish by today’s standards, but it struck a responsive chord with affluent late Victorians. One special request Ward fulfilled involved preparation of a pet skunk. “I have never forgotten the aroma of that beast to this day,” he later wrote. “I verily believe it could have been detected from one end of Piccadilly to the other.” That was an undertaking he chose not to repeat.

An early 20th century Rowland Ward taxidermy model of the head and shoulders of a male lion, mounted within a glazed bamboo case. photo: Bonhams

Ward’s list of clients and circle of friends read like a veritable “Who’s Who” of sportsmen and natural historians of the time. Among his close friends were scientists such as Charles Darwin, Sir Joseph Hooker and Sir Richard Owen. Renowned hunters such as Fred Selous, Sir Samuel Baker and Arthur Neumann frequented his premises, and he published books by Selous and Neumann. Whenever international hunters passed through London, Rowland Ward’s was a “must visit” site, and country sportsmen coming to the great city from their country estates invariably stopped by to rub elbows with others of similar interests and check out the latest trophies brought home from Asia or Africa.

Ward’s appreciable talents as an artist and sculptor were perfectly complemented by his gregarious “hale fellow well met” personality, but he was also a man with a distinctly scientific bent of mind. Numerous new species of animals came to have wardi as part of their scientific name. He frequented the zoo at Regent’s Park on an almost weekly basis, visiting it with the express purpose of obtaining the fullest possible image of the posture and behavior of species he would be mounting. Many of the techniques he pioneered came from his habit of astute observation. Among these was using what he called “wood wool” to stuff specimens and get an appropriate shape. He also developed a naturalist’s camera, introduced the use of carbolic acid as a preservative and gave sportsmen detailed printed instructions for the proper handling of specimens intended for mounting. The latter took the form of a book that was his first significant venture into the world of publishing, Rowland Ward’s Sportsman’s Handbook to Collecting and Preserving Trophies and Specimens. Initially offered in 1880, it went through at least 11 printings over the next 33 years. The book’s warm reception formed the backdrop for Ward becoming a major publisher of sporting books.

An exceptional snow leopard skin with mounted head, circa 1920.

Paralleling his venture into the world of sporting literature was a less remunerative but undeniably important service of inestimable benefit to sportsmen. He began to serve as a sort of informational clearing house for hunters planning trips to Asia or Africa. As he wrote, “I was always anxious to foster the wish of men of wealth and position to go and hunt wild beasts in all parts of the world…and many gentlemen have thanked me for introducing them to ‘the calls of the wild.’” One such gentleman was Theodore Roosevelt, who wisely sought Ward’s advice as he planned his grand post-presidential safari in Africa. Ward generously offered TR his services free, as it was indeed his normal approach in this regard. Of course, his goodwill normally paid handsome dividends when it came to the pre-hunt sale of equipment and post-hunt mounting of trophies.

Each passing year saw his fame increase, accolades increase and medals multiply. As a result, early in the 20th century, he was able to add to his letterhead the coveted words “By Appointment to His Majesty, the King, Naturalists.” On more than one occasion Ward’s full-body mounts of lions and tigers caused near pandemonium when train box cars were opened to reveal them. For example, when one of his superb efforts, “A Tiger at Bay,” was transported to its owner at a small country railway station, a mischievous porter removed it from the transport carriage and situated the mount on the main road leading to the station just minutes prior to the scheduled arrival of the regular morning passenger train. Panic ensued, with horses bolting and a horse-drawn carriage being overturned. Rustic locals required several hours and some frantic telegrams before they summoned sufficient courage to “approach the animal and discover its innocuousness.” Understandably, Ward took joy in such incidents. They offered graphic examples of the high degree of authenticity represented by his mounts.

A full mount of a male African antelope.

Although he introspectively acknowledged being so immersed in his job as to “call work my wife,” Ward actually pursued multiple interests connected with his labors. He experimented with duck breeding and merits a fair share of credit for popularizing the Labrador as a hunting retriever. He successfully crossed the native British breed of pheasants with the Mongolian variety and introduced these on his estate, Necton Hall, near Swaffham in Norfolk. The resultant shooting proved excellent, and the new breed of pheasant tolerated severe weather well. They were so nicely suited to English conditions that soon gamekeepers across Britain were breeding them on a widespread scale.

Ward married rather late in life, and the perspective of Mrs. Ward was one many a harried sportsman inclined to spend too many idle hours on field or stream has to appreciate. In sharp contrast to the stereotypical male resorting to all sorts of tricks and dodges to escape his spouse for a few hours of hunting or fishing, she encouraged him to work less and hunt more. She was, in the lingo of the era, “no screamer.” In 1897, the couple took an expedition that for Ward had long been the stuff of dreams.

An unusual Roman walnut chair with deer feet. photo: Spectandum

A decade and a half earlier, a client had shown him a single scale from a massive tarpon and described the fish in graphic detail. So greatly was Ward impressed that he forthwith determined that he would, at some point in the future, make a trip to Florida and come to grips with the mighty fish. When that finally happened, Ward and his wife did things in style. They sailed to New York on the luxurious S. S. Majestic. There they enjoyed several days of relaxation and some visits with American clientele along with purchasing a great amount of equipment. Then the couple set out on a leisurely southern fishing pilgrimage that also devoted considerable time to retracing the footsteps his father had trod, decades before, while working with Audubon.

The grand adventure proved a glorious success. He caught a satisfying number of large tarpon and gained real appreciation for his sire’s studies in natural history. Even today, more than a century after Ward’s account of the angling aspects of the experience, the book he titled The English Angler in Florida offers enjoyable reading. Published under his own imprint, the work is, like all original Rowland Ward books, a valued collector’s item.

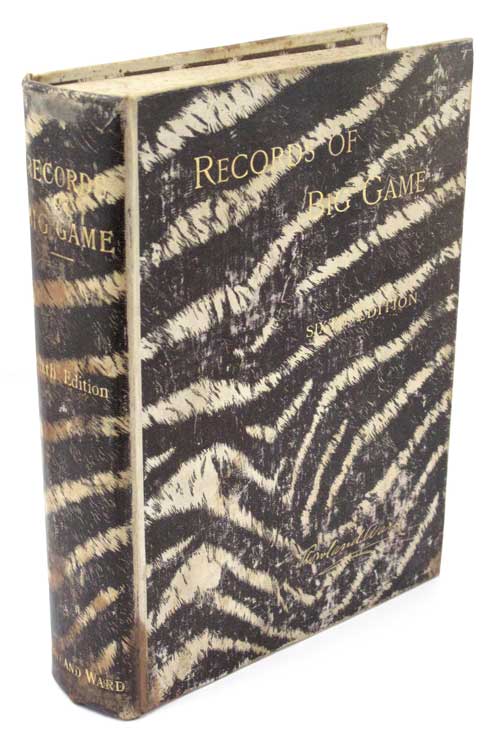

Of course today, as has been noted, his name is most commonly associated with The Records of Big Game. First published in 1892, each succeeding edition of this massive volume has updated and occasionally corrected its predecessors. Yet for all the unquestioned and enduring importance of the 30 editions of The Records of Big Game, it is the three dozen plus other works printed by Rowland Ward (some in multiple editions or different formats), which are of the greatest interest to sporting bibliophiles.

Featuring contributors such as Richard Lydekker, Prince San Donato Demidoff, Fred Selous, Major P. H. G. Powell-Cotton, Theodore Hubback, Paul Niedieck and other notables, the books chronicle hunting and natural history on five continents, with the major subject thrust being Asia and Africa. Not only did Ward publish authors intimately familiar with their subjects, the actual books are works of art. They feature fine binding, zebra stripe endpapers, lavish illustrations and more. One of them, Count Joseph Potocki’s Sport in Somaliland, published in a quite small edition of 200 copies, is among the great rarities in sporting literature.

Notwithstanding his extended sporting vacation in the United States late in life, predictably this man possessed of an exceptional work ethic labored tirelessly right to the end. He was also fortunate, chronologically speaking, in the sense that his life was, in his words, “co-existent with the rise and progress of the greatest hunters of big game.” Ward played an important role in the growth and development of the British Museum of Natural History’s collections, and that venerable institution’s leaders regularly turned to him for advice. When he died on December 28, 1912, Rowland Ward was, as his obituary notice in The Times put it, “perhaps the best-known taxidermist in the world.” He was also an author and publisher of note, a long-time Fellow of the Zoological Society and enthusiastic amateur scientist who made lasting contributions to various areas of study in natural history and a consummate sportsman ever eager to advance the pleasure and enjoyment others garnered from the outdoors. He was, in short, something of a Renaissance man of sport as well as the father of modern taxidermy. His myriad contributions were and remain a rich legacy. ν

Jim Casada is Editor at Large for Sporting Classics and a lifelong student of the history of hunting and fishing. To learn more about his work or to receive his free monthly e-newsletter, visit jimcasadaoutdoors.com, or check out books offered through the sporting Classics Store.