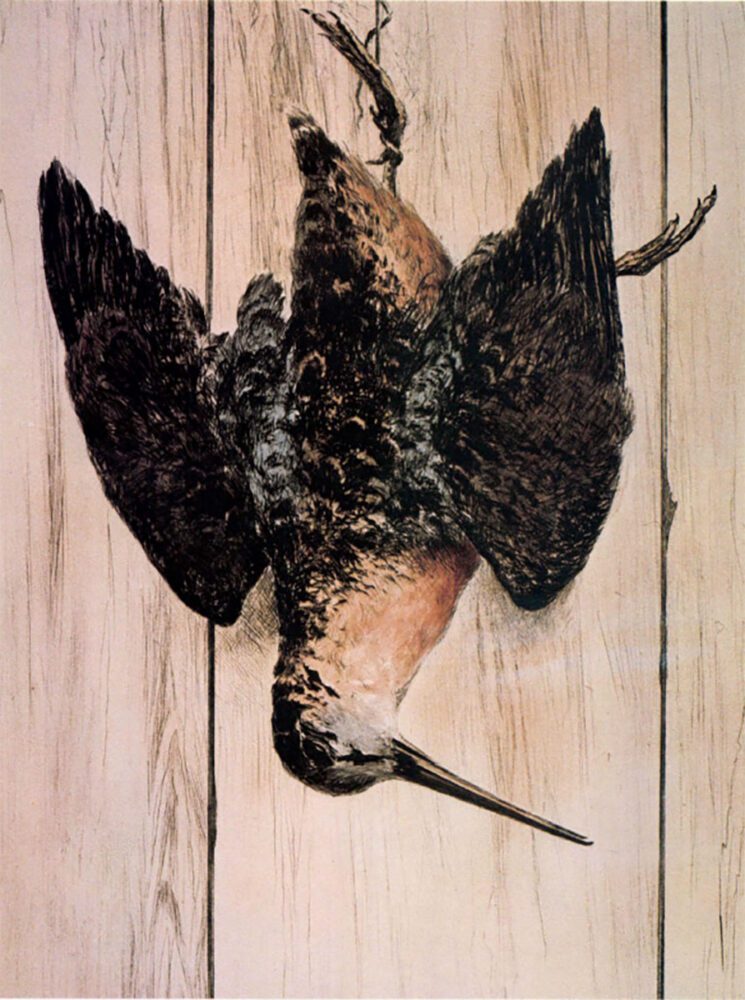

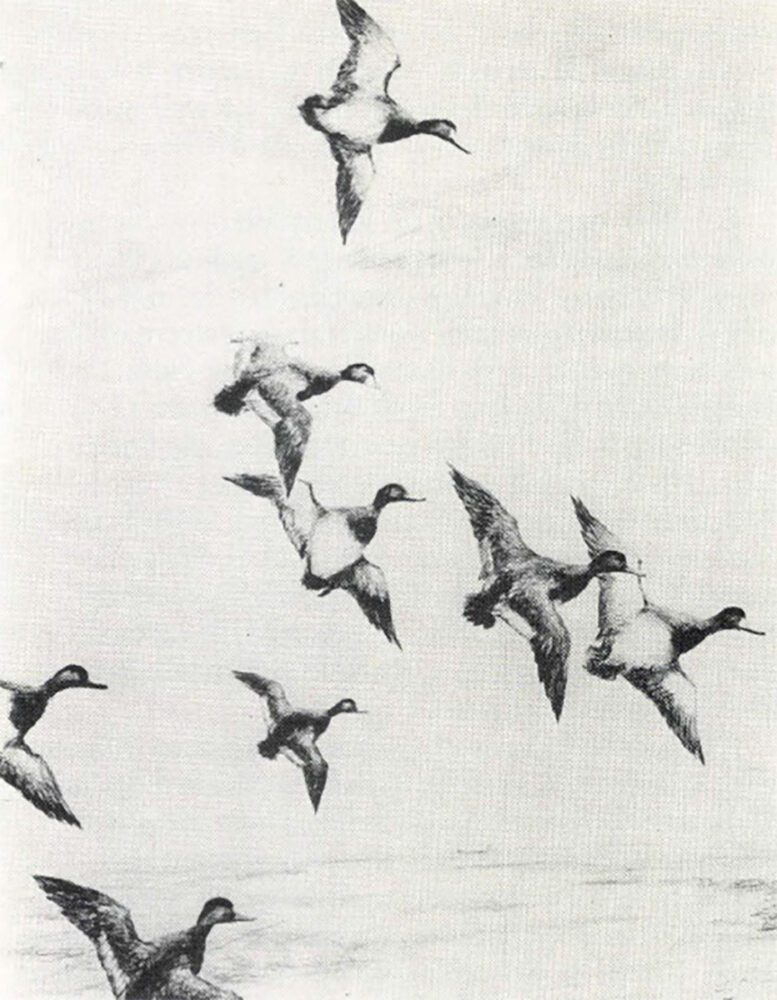

Roland Clark’s love of excellence extended beyond duck portraiture.

More than other hunters, waterfowlers are men sustained by memory and promise. In the icy silence of the marsh, when a world of water and sky hangs suspended between darkness and daylight, a man looks inward and finds the reason he is here at this place, at this time.

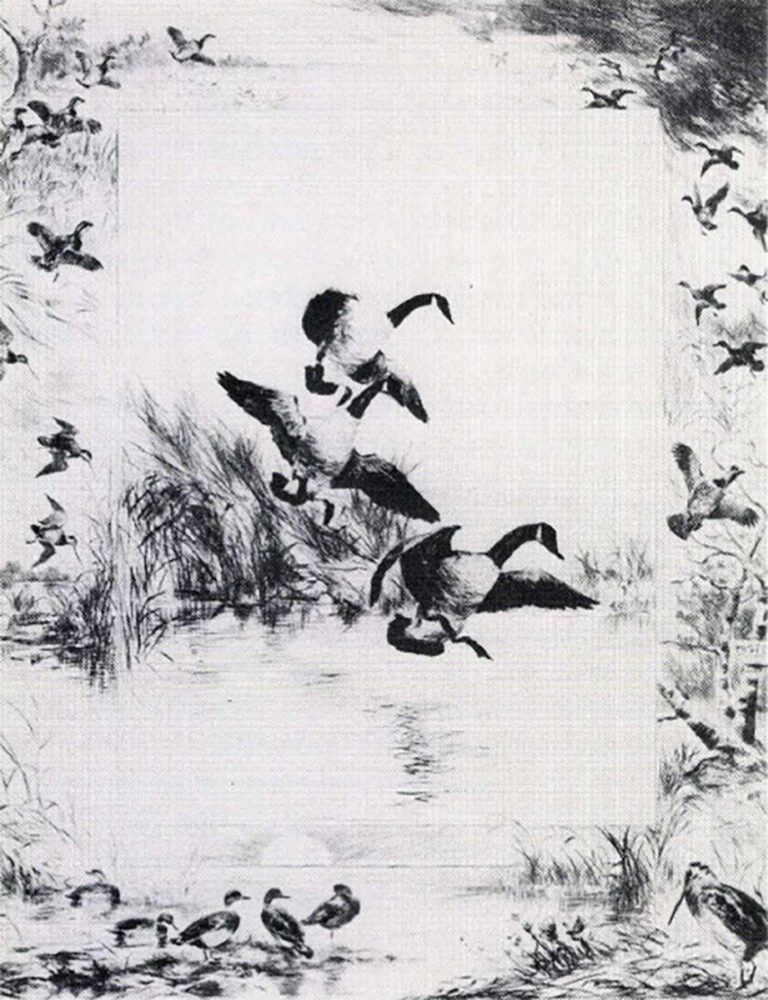

The stars glimmer coldly in the hard sky those last few moments before fingers of rosy light rim the eastern horizon. Small flocks of phantom fowl, their passing marked only by whistling softened beats in the darkness, take shape against the onrushing backdrop of colored light. The numbing cold of the blind seems to recede with the darkness, and already the eye is measuring speed and distance, gauging the moment when the next bunch will swing over the decoys within range of the gun. At this instant all the rich sensations of similar mornings which have gone before merge with expectations of the future, and all the sights, sounds, smells and colors of these brief seconds embed themselves deeply in the mind. Roland Clark captured these moments the way a hunter sees them. His art contains the life and vigor of the hunting experience.

The stars glimmer coldly in the hard sky those last few moments before fingers of rosy light rim the eastern horizon. Small flocks of phantom fowl, their passing marked only by whistling softened beats in the darkness, take shape against the onrushing backdrop of colored light. The numbing cold of the blind seems to recede with the darkness, and already the eye is measuring speed and distance, gauging the moment when the next bunch will swing over the decoys within range of the gun. At this instant all the rich sensations of similar mornings which have gone before merge with expectations of the future, and all the sights, sounds, smells and colors of these brief seconds embed themselves deeply in the mind. Roland Clark captured these moments the way a hunter sees them. His art contains the life and vigor of the hunting experience.

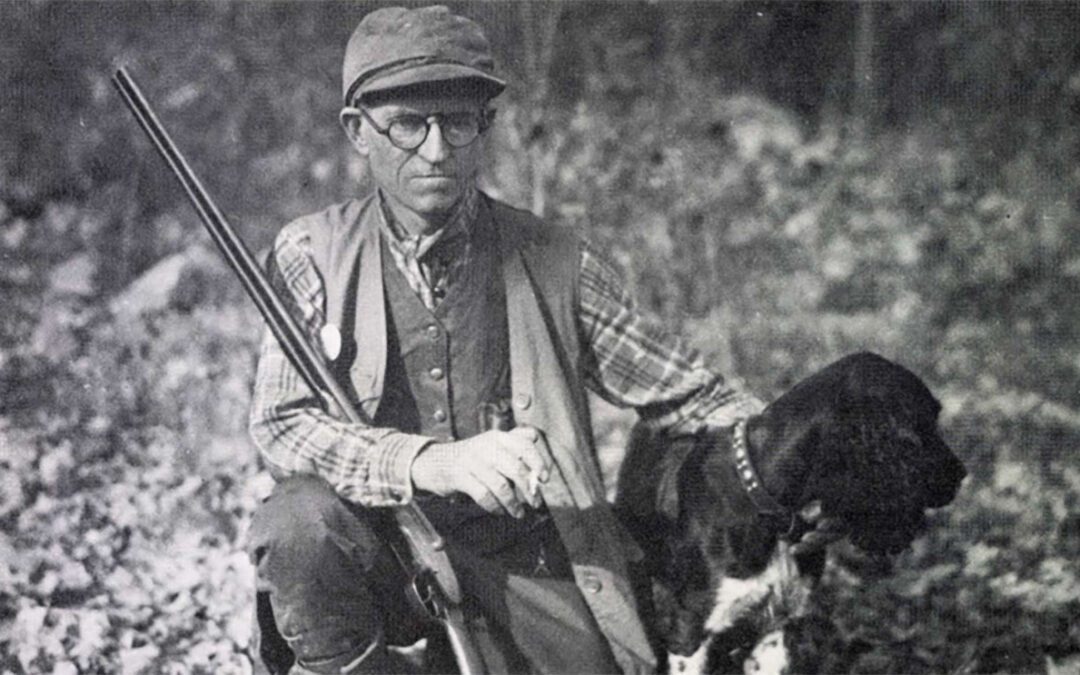

It is not surprising that there is a certain quality in Clark’s work that appeals to the hunter, for hunting was a central part of Roland Clark’s life. Born April 2, 1874 in New Rochelle, New York, he was the son of Henry Walker Clark, a New York lawyer, and Fanny Elizabeth C lark. The family’s home was but a short distance from the marshes of Long Island Sound and Roland, along with his two brothers, discovered the delights of this watery world at an early age. With the legions of waterfowl that could be found there and along Great South Bay in those halcyon years before the turn of the century, it is small wonder that a young duck hunter’s interests should revolve around a few of life’s simple things. Perhaps reflecting on the way he spent his time in those far off days, he penned the following words in the Foreword to Pot Luck:

“Transcending all other matters engaging my attention was a sawed-off musket of ’63 and the problems of securing ammunition to charge the same. I am sure this deadly weapon occupied more of my time and thought than anything else in the world.”

Art and hunting were youth’s twin passions, and long days afield and on the water sustained both. He began to sketch when quite young, and his formal education in art continued under private instructors and late r at the Art Students League in New York where he studied under J. Carroll Beckwith. It was the marshes and later, the uplands too, that were his most valuable classroom. He had the hunter’s desire and the artist’s eye and nothing, from the light brown of the marsh grass to the tint of dawn breaking the eastern horizon, escaped him. He never painted from photographs, for he did not need to. Countless days afield had burned color, form, motion and perspective into his mind’s eye, and if, in later years he sometimes rendered his subjects with the optimism of days long past, he honestly admitted it:

Art and hunting were youth’s twin passions, and long days afield and on the water sustained both. He began to sketch when quite young, and his formal education in art continued under private instructors and late r at the Art Students League in New York where he studied under J. Carroll Beckwith. It was the marshes and later, the uplands too, that were his most valuable classroom. He had the hunter’s desire and the artist’s eye and nothing, from the light brown of the marsh grass to the tint of dawn breaking the eastern horizon, escaped him. He never painted from photographs, for he did not need to. Countless days afield had burned color, form, motion and perspective into his mind’s eye, and if, in later years he sometimes rendered his subjects with the optimism of days long past, he honestly admitted it:

“Doubtless youth sees with a glamorous eye, magnifying certain pictures and treasuring memories of them for all the years to come. I believe I had that sort of eye. A hundred ducks were a thousand; the geese filled all the sky. There were forty quail in an average covey — once upon a time.”

Roland Clark was remarkable because he was an artist who also wrote well. While the two art forms are by no means exclusive, it is doubly rewarding to find an artist whose prose complements his artwork so well. His style had a gentle leanness to it, expressive without being overdone or wordy. He wrote and illustrated three books: Stray Shots (1931), Gunner’s Dawn (1937) and Pot Luck (1945). The stories could well have been published on their merit without the support of Clark’s artwork.

Clark the author drew on his youthful experiences just as did Clark the artist. Those gunning tales which center around his early years on Great South Bay are especially interesting as authentic accounts of waterfowling techniques of the times. It is in his story “The Log of a South Bay Cruise” from Stray Shots that he describes the near-forgotten experience of ice-hole shooting in the years just before the turn of the century. Clark and his friends, having made the journey across the sound and overland to the bay, find the waters ice-bound. Gloomily surveying the frozen expanses before them, the wind carries to their ears the distant sound of gunfire. They investigated and found:

Clark the author drew on his youthful experiences just as did Clark the artist. Those gunning tales which center around his early years on Great South Bay are especially interesting as authentic accounts of waterfowling techniques of the times. It is in his story “The Log of a South Bay Cruise” from Stray Shots that he describes the near-forgotten experience of ice-hole shooting in the years just before the turn of the century. Clark and his friends, having made the journey across the sound and overland to the bay, find the waters ice-bound. Gloomily surveying the frozen expanses before them, the wind carries to their ears the distant sound of gunfire. They investigated and found:

“…But one open space of water remains, and why, unless influenced by some warm springhole, this tiny spot should have kept from freezing I am sure I cannot say … I believe the gunner (who had it) slept in the marsh jealously guarding his find. At last, one day, we beat him to it and quickly set out our decoys.

I have since shot on some of the greatest ducking grounds in the world . . . But never have I seen more ducks to a given area than I did our first morning on Cedar Island.

As soon as we set out . . . the shooting began. We had no time to hide the boat; we didn’t have to . . . we whanged away till our barrels scorched us; . . . I shan’t say how many we had . . ..”

Clark eventually became dissatisfied with New York and an invitation from a school chum Ottway Byrd lured him to Virginia. There, at Whitehall Plantation, the ancestral home of the Byrd family on Mobjack Bay near Gloucester, he met Ann Byrd. They were married on September 5, 1900.

The artist found a home in Virginia in more than one sense. After their marriage, the Clarks were presented with a parcel of land from the plantation and eventually took up residence at Ann Field, as their home would be known. In addition, ducks and geese were abundant on Mobjack Bay and in the surrounding Chesapeake region, and the autumn uplands were filled with quail. It was as much as any gunner or artist could ask for, and he spent the next 22 years there, hunting and sketching in fields and marshes near home.

Although perhaps best know for his etchings and dry points (a type of intaglio where the design is scratched into the plate with a needle or other pointed instrument, the resulting ridges on either side holding ink during the printing process and imparting a delicate and somewhat indistinct appearance to the line), he seems to have worked little in these media during his years in Virginia. He painted in oils, wrote verse and prose, and began to do pen and ink sketches. He sold a few paintings in Baltimore, Richmond and other cities. This modest success encouraged him to continue to shoot, to paint and to write. He set up a small studio in a building separate from the main house at Ann Field, and was apt to be found there nearly any time of day, for he observed no particular work routine. Time spent afield with gun and dog was as much work time for Roland Clark as any hour spent in his studio. Dawn in a duck blind or an afternoon in the quail coverts was the time to gather the raw materials of creativity.

Although perhaps best know for his etchings and dry points (a type of intaglio where the design is scratched into the plate with a needle or other pointed instrument, the resulting ridges on either side holding ink during the printing process and imparting a delicate and somewhat indistinct appearance to the line), he seems to have worked little in these media during his years in Virginia. He painted in oils, wrote verse and prose, and began to do pen and ink sketches. He sold a few paintings in Baltimore, Richmond and other cities. This modest success encouraged him to continue to shoot, to paint and to write. He set up a small studio in a building separate from the main house at Ann Field, and was apt to be found there nearly any time of day, for he observed no particular work routine. Time spent afield with gun and dog was as much work time for Roland Clark as any hour spent in his studio. Dawn in a duck blind or an afternoon in the quail coverts was the time to gather the raw materials of creativity.

During his years in Virginia, Clark worked for a short time in the oyster trading business. The world of commerce proved not to his liking, nor, perhaps, did he find himself well suited for it. Had he remained in the oyster business, the world might well have been denied the work for which he has become best known and justly famous.

In the early 1920’s he sold his Virginia property and returned to New York City. Wishing to market his artwork, he took some of the pen and ink sketches he had done to Philip Suval, a New York art dealer. Suva I quickly recognized Clark’s artistic talent, but pointed out to the artist that his beautiful sketches lacked commercial prospects because they could not be reproduced. If you can etch these, Suva I told him, you have a bright future. Taking Suval’s advice, Clark promptly purchased the necessary tools and began an intensive study of the etching process. That he rapidly mastered etching as an art form without benefit of formal instruction is a tribute to his skill and desire. An item in The New York Times of September IS, 1927 recognized Clark’s accomplishments:

“. . . Roland Clark is anyone’s equal on the side of duck portraiture. His recent work is the best he has done … The artist who cares first for nature, and, after nature, art, never misses in his portraiture of wild creatures (their) power to get away. The printing of Mr. Clark’s etchings has also improved. He is not his own printer, but each impression is made under his supervision, and he either is growing more exacting or his printer has developed greater skill. A number of the recent plates have yielded proofs of delightful quality, with just the right blend of delicacy and freshness.”

“. . . Roland Clark is anyone’s equal on the side of duck portraiture. His recent work is the best he has done … The artist who cares first for nature, and, after nature, art, never misses in his portraiture of wild creatures (their) power to get away. The printing of Mr. Clark’s etchings has also improved. He is not his own printer, but each impression is made under his supervision, and he either is growing more exacting or his printer has developed greater skill. A number of the recent plates have yielded proofs of delightful quality, with just the right blend of delicacy and freshness.”

Roland Clark’s love of excellence extended beyond “duck portraiture,” as the Times put it. He loved fine horses, dogsand guns. He owned and shot some of the world’s premiere shotguns: Parker, Purdey, W & C Scott, Daly Diamond Quality. His wide circle of shooting friends often extended an invitation to hunt waterfowl or upland game in Canada or Scotland. He loved the driven grouse shoots of the highlands, perhaps as much for the colorful tradition of the event as for the gunning itself. He was charmed and fascinated by the school children who often acted as “beaters” to drive the feathered rockets toward the gunners waiting in the butts. As skilled with a shotgun as he was with engraving tools and paintbrush, he was acknowledged to be a fine wingshot.

A modest man in spite of his accomplishments, he was demanding and critical in appraising the quality of his own work. By contrast, he always complimented the work of others. He knew personally many of the prominent wildlife and sporting artists of the times — Lynn Bogue Hunt, Carl Rungius, Richard Bishop, Frank Benson. He particularly admired the work of Benson and Peter Scott, the British artist. A member and enthusiastic supporter of Ducks Unlimited, he often contributed his artwork for the benefit of the conservation organization. Even at D.U. dinners he shunned the limelight, usually finding a seat somewhere towards the back of the room. When called on to stand, he would rise briefly, slipping up his hand in acknowledgement, and then return quickly to his seat.

Although he had many friends and acquaintances he shot with, he loved to hunt alone, perhaps finding in the solitude of the marshes and uplands the freedom from distraction which his work required. He felt strongly that ancient hunter’s need for involvement in all the details of his sport. He saw to the breeding of his own bird dogs, cooked his own game, carved his own working decoys. Wanting a decoy that simulated a feeding bird, he fashioned one with a retractile head which disappeared into the water when the hidden gunner pulled the controlling cord.

Although he had many friends and acquaintances he shot with, he loved to hunt alone, perhaps finding in the solitude of the marshes and uplands the freedom from distraction which his work required. He felt strongly that ancient hunter’s need for involvement in all the details of his sport. He saw to the breeding of his own bird dogs, cooked his own game, carved his own working decoys. Wanting a decoy that simulated a feeding bird, he fashioned one with a retractile head which disappeared into the water when the hidden gunner pulled the controlling cord.

The 1920s and early 1930s were prolific ones for Roland Clark’s etchings. He did a considerable number during these years, many of them in issues of 50 to 75 copies, although the number of an issue might be as low as 30 or as high as 100.He worked intermittently in oils and watercolors throughout a large part of his life. A surprising quantity of his original art, in addition to considerable number of his etchings, seem to have been sold overseas.

Although Clark’s reputation was secure before his association with Derrydale Press, the artist is remembered by many for the beautiful limited edition books he wrote and illustrated, as well as for the limited edition aquatints he produced for Derrydale. He did three books for Derrydale, two of which-Stray Shots and Gunner’s Dawn-showcased his prose and art, while the third – Roland Clark’s Etchings — contained 70 reproductions of his etchings. All these titles were issued in both regular and deluxe editions, and like most other Derrydale titles have risen dramatically in value over the years.

From 1937-1946, Clark did a series of aquatints (prints water-colored by hand), first for Derrydale and later for Frank J. Lowe. TI.is process entailed the artist doing an oil or watercolor, reprinting the outline, and the artist hand-coloring an artist’s proof. The proofs and the printed outlines would then be passed off to other artists who would hand-color the limited issue in accordance with the proof. Finally, the artist or the publisher would approve the coloring and the print would be signed and numbered. Twenty of these aquatint issues were done during the period 1937-1946 in editions of 250 each.

These hand-colored prints displayed some of Roland Clark’s most admired and coveted waterfowl work. The Alarm a single black duck done in 1937, is thought by some to be one of the finest examples of this species ever created by an artist. Similarly, Mallards Rising done in 1942, is a multiple duck scene held in the same high esteem as The Alarm. Predictably, these two prints today command premium prices on the collector market. When first released, many of these prints sold for $25. Today, “The Alarm” and Mallards Rising will bring $1,200 to $1,500.

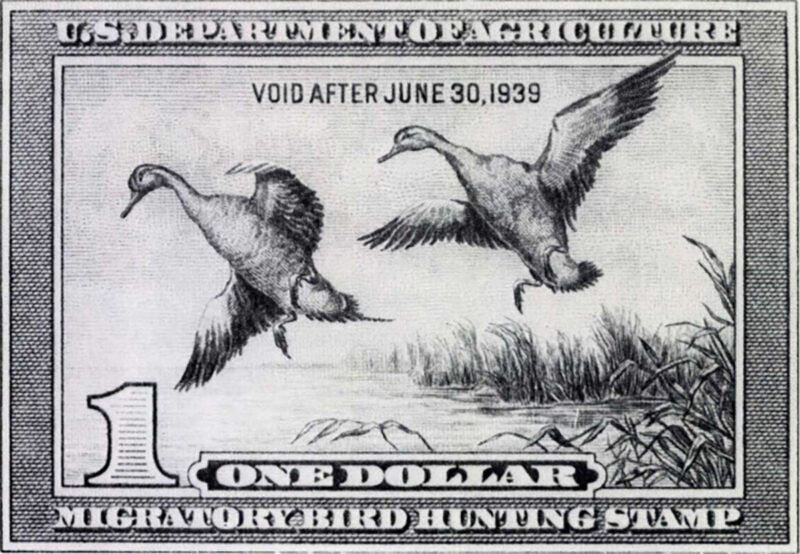

In 1938, the U.S. Department of the Interior accepted his design for the federal duck stamp. Clark’s favorite duck was the pintail, and the 1938 stamp shows two pintails alighting. Actually, the two birds shown on the stamp were the central ducks taken from an etching done in 1933 and issued in an edition of 75.

In 1938, the U.S. Department of the Interior accepted his design for the federal duck stamp. Clark’s favorite duck was the pintail, and the 1938 stamp shows two pintails alighting. Actually, the two birds shown on the stamp were the central ducks taken from an etching done in 1933 and issued in an edition of 75.

During his life Roland Clark executed approximately 500 etchings. This production was supplemented by a substantial number of oil paintings, some watercolors, and pen and ink sketches. In addition, he did over 400 miniatures and prepared the original design for a number of other items, including neckties, coffee cups and drinking glasses.

While advancing years may have drained him of the vigor to pursue the rugged life of a hunter, he continued to work long after he had racked his shotguns for the last time. Even two cataract operations could not keep him from his art, and at age 82 he was still painting his waterfowl on lockets. He died at the age of 83 in Norwalk, Connecticut on April 13, 1957.

It has sometimes been said of Roland C lark that he was often tom between the desire to shoot a duck and to sketch it. To be sure, he did a lot of both. If his art is the measure of his contribution to the preservation of waterfowl, then surely more birds live than ever died because of him. The Foreword to Potluck illuminates the man and his purpose:

It has sometimes been said of Roland C lark that he was often tom between the desire to shoot a duck and to sketch it. To be sure, he did a lot of both. If his art is the measure of his contribution to the preservation of waterfowl, then surely more birds live than ever died because of him. The Foreword to Potluck illuminates the man and his purpose:

“To picture them on canvas and copperplate; to give them true resemblance of life has been my earnest endeavor for many, many years . . . In (this book) I have tried to do this, hoping each little painting will call to mind for you who see it a day when . . . shivering in a windswept blind, (you) still stuck it out in the greatest sport on earth.”

Well, there it is. Memory and promise. Somewhere, in the congealed gray clouds, wind ripped marsh grass and the purposeful power of a flock of mallards swinging to the stool stirs the recollection of a hundred cold dawns. Deep in your heart stirs the promise, the hope, of a hundred more.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in 1982’s Volume 1, Issue 6 of Sporting Classics.

Through the images of award-winning photographer Gary Kramer and the words of Kramer and Greg Mensik, Waterfowl of the World takes readers on a visual and literary journey in search of all 167 species of ducks, geese, and swans on Earth. Buy Now

Through the images of award-winning photographer Gary Kramer and the words of Kramer and Greg Mensik, Waterfowl of the World takes readers on a visual and literary journey in search of all 167 species of ducks, geese, and swans on Earth. Buy Now