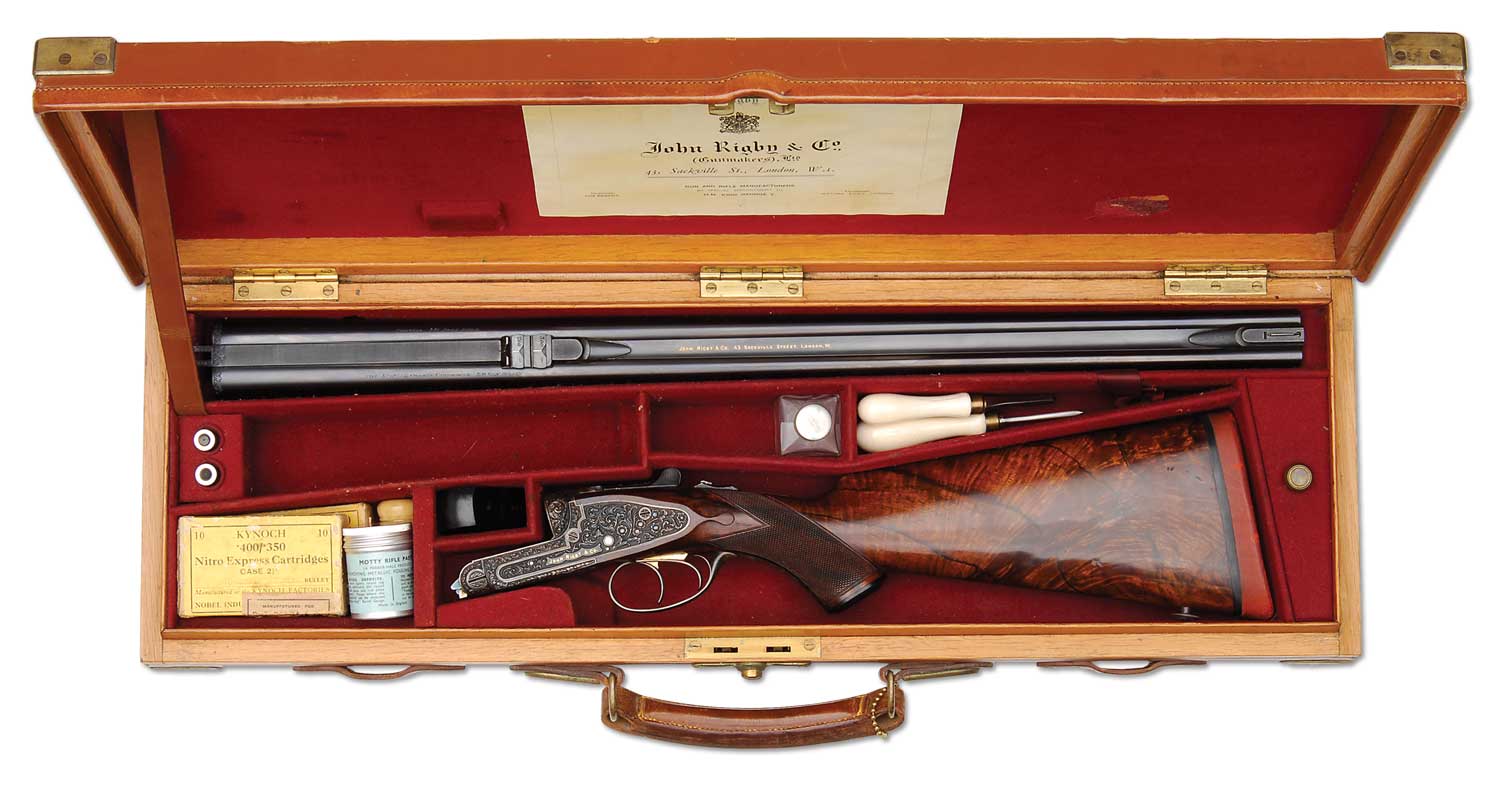

A growing appetite for firearms with unique signature features is prompting change in the British gun trade. Following Westley Richards’ successful reintroduction of its broad top-lever and doll’s head extension, John Rigby & Co. is once again building rising bite guns and rifles.

Under a strapline that reads, “A re-emergence of traditionalism,” we are told that “The patent dates back to 1879 and was the brainchild of Thomas Bissell, a gunmaker who collaborated with John Rigby on several projects and made guns for him in the mid- to late-1800s. The vertical bolt secures the barrels tight to the action face and provides a third bite in addition to the traditional double bolt.”

Distinguishing design elements are what set otherwise similar guns apart. Their resurrection by the British gun trade speaks to our idea of difference, but also novelty. Three recent examples are the Grant sidelever, the skeletal-bodied Macnaughton round action and the previously mentioned Westley Richards doll’s head and top-lever.

Traditionally, Rigby guns and rifles have employed their dipped edge lock-plate engraved with makers name in blackletter as an instantly recognizable signature feature. Ostensibly about creating a stronger shotgun or rifle, the Rigby and Bissell U-bolt provides yet another element that is aesthetically unique.

Illustrious histories are not unusual within the English gun trade, but Rigby’s is peculiar in that it transcends Britain. Rigby began life, not in England, but in Ireland. The current iteration of John Rigby & Co. based in London claims a startup date of 1775 “…which places us as the oldest gunmaking firm in continuous existence in the English-speaking world.” However, John Rigby first appeared in Dublin street directories during 1784 when he claimed he had been previously employed, “as a workman by the most eminent makers of Dublin,” who employed him for upward of ten years. Rigby was also proud to state: “Real Irish Manufacture” and “Equal to any made in London.” In 1816 the founding John Rigby took his eldest son William into partnership and the firm became “John Rigby & Son.” William was later joined by his younger brother John Jason Rigby.

Foremost amongst Rigby distinctive features during the time that percussion ignition swept the flintlock aside were the use of back-action locks in which the mainspring is placed behind instead of in front of the hammer. In this regard, Rigby “anticipated the majority of English gunmakers by twenty or thirty years” wrote J. N. George in English Guns and Rifles, adding that in Dublin they were the “acknowledged heads of the trade.”

As well as beautiful banana-shaped back-action locks curving into the wrist of its guns, Rigby added luster to its Damascus barrels by “pickling” them in acid, once again anticipating its London rivals. By most accounts, the Rigby family were crack rifle shots with successive generations following in this tradition. To this day, Rigby enjoys a strong reputation for building best rifles, both bolt-action and double.

Sometime mid-century, Queen Victoria’s husband, Prince Albert, had the idea of an exhibition to impress the world with Britain’s technical achievements. Held in The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, London, during 1851, it was attended by six million people where 138 manufacturers of small arms showed their wares.

W. & J. Rigby, then of Suffolk Street, Dublin, was one of them. While the Great Exhibition was a tremendous success, exposure to international competition proved something of a rude awakening for the British gun trade whose exhibits were upstaged by the French in terms of design flair. Lefaucheux of Paris caused the biggest bang with a drop-down breechloader not dissimilar in concept to today’s standard side-by-side.

The problem was that the French gun was not particularly strong. While it’s not difficult to imagine the criticism from the 65 native gun trade representatives, it’s also clear that some were sufficiently impressed to see its potential. In the following years, Rigby offered a variety of breechloaders built in cooperation with other British gunmakers—Joseph Needham, James Dalziel Dougall and William Norman—but with limited success.

In the search for sound lockup in drop-down breechloaders, one early development was Westley Richards doll’s head gun in which the barrels have an extension of the top rib that fits into a correspondingly shaped recess in the top of the standing breech. Even more important was the Purdey double bite under bolt where a flat rectangular piece of steel secures the barrels by engaging slots cut into their under-lumps.

Simplicity itself, the Purdey under-bolt became a worldwide standard for break-open guns and is in universal use to this day. The Westley Richards doll’s head—though it never enjoyed the same all over appeal as the Purdey under-bolt—does appear to have precipitated a tsunami of inventive ideas. Of these, perhaps the W. W. Greener with its eponymous cross-bolt is best remembered.

In the late 19th century, sportsmen were spoiled for choice when it came to these treble bite guns with their Purdey under-bolts and top fasteners. They were particularly popular on heavy fowlers and big double rifles. The year after the Purdey under-bolt was introduced, the following appeared between the pages of The Field: “John Rigby and Co. of Dublin beg to inform their numerous customers in England that they have opened a branch establishment at 72 St. James’s Street, London. They are now manufacturing to order.” There then followed a list of offerings with a heavy emphasis on rifles.

In 1887, John Rigby III was appointed Superintendent of the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock with a mandate to transition British military rifles from single-shots using blackpowder cartridges to smokeless powder bolt-action repeaters. John Rigby’s elevation to the post was greeted “with satisfaction and relief” by Teasdale-Buckell who said, “It was thought he was the right man to superintend the manufacture of arms he could use so well.” It also did nothing to harm Rigby’s reputation for rifles.

Just a few years previously, Rigby had introduced its unprecedentedly strong rising bite in which a vertical bolt engages with a slot in the center of a U-shaped top extension. As a group, rib extensions such as Westley’s doll’s head and Greener’s cross-bolt, were seen by the driven bird elite as “awkward” and a “minor hindrance,” or so said Major Hugh B. C. Pollard. Sir Ralph Payne-Gallwey was even more demonstrative: “The chief disadvantage of the top extension besides its clumsy appearance is that the cartridges are not, owing to its presences, readily extracted when the fingers are cold, as the projection of the rib is in the way at all times.”

To put these seemingly nit-picking judgements into perspective, it’s important to understand that at the time, crack shots such as Ripon and Walsingham were competing to kill huge bags of driven birds using pairs and sometimes trios of preloaded shotguns. Even tiny improvements were seen as critical.

Sir Major Gerald Burrard writing in The Modern Shotgun provided clarity when he wrote: “Ease of loading is a very important point, and it depends on the presence or absence of a top extension as well as on the extent of the drop of the barrels. Some extensions are very clumsy and interfere appreciably with the work of loading.” Burrard then trumpets the virtues of the Purdey concealed extension writing that it “certainly has the advantage over extensions of the doll’s head and cross-bolt type that it does not interfere in any way with the work of loading.” That observation, soon to be a century old, has lost little of its truth.

Rigby did build shotguns with its famous top fastener, but they were never received with the enthusiasm of its double rifles. Over the years, the Rigby and Bissel top fastener fell into desuetude. It was time consuming to fit, expensive to build and ultimately not as appropriate as other designs in the eyes of shotgunners.

Those of us with an interest in British fine guns watched as John Rigby & Co. experienced two long decades of tribulations. In 1997, longtime owner Paul Roberts sold the name to Americans who leased manufacturing rights to a company in Paso Robles, California. In 2010, the company passed to two Texan businessmen and led to L&O Holding buying the company from Rigby Ventures Inc. and putting it back in English hands in London. On the 17th of April 2014, Rigby Gunmakers Ltd. was registered at Companies House and a month or so later the name was changed to John Rigby & Co (Gunmakers) Ltd.

The new owners understood that unique signature features were significant to buyers of British guns and rifles and began the difficult process of recreating the Rigby and Bissel mechanism. The Rigby and Bissel has garnered a strong reaction from sports headed to Africa. For those wanting a full and traditional experience of dangerous game, the overwhelmingly preference today is for the double rifle over the bolt gun. A Rigby double rifle with its nostalgic slant offers a physical link to a romantic past.

From its Dublin origins, London base and forays to California, plus a traditional client base in Africa, John Rigby & Co. represent an important component of the ever-deepening connectivity that defines the modern world. Its double rifles with the Rigby and Bissell U-bolt are part of a welcome and newish trend to offer unique signature features from the golden age that are as pertinent now as when they were first introduced. The Rigby and Bissel rising bite is emblematic of the very best in dangerous game stopping rifles. For a new generation venturing into Africa, Rigby has the rifles for them.

This article originally appeared in the 2021 Guns & Hunting issue of Sporting Classics magazine.