Recoil. It doesn’t have to be painful. But will a rifle with less recoil compromise your ability to terminate what you shoot?

You’ll get a kick out of this. Lord knows the Kid did. His name has been changed to minimize his embarrassment. We told him the bleeding would stop, but his mother insisted he go into the clinic for stitches. “Hey, Kid, don’t worry. Recoil happens.”

But “scope-eye” doesn’t have to.

When the equal and opposite reaction to the action of 60,000 psi of gas pressure propelling a 200-grain, .308-inch diameter chunk of copper and lead down a .300-inch diameter barrel is halted by the convergence of the rim of your riflescope against your occipital ridge, you are inspired to find a rifle and/or cartridge with less recoil. But will that compromise your ability to terminate what you shoot?

This tradeoff between shootability and game-stopping power is a perennial conundrum. What’s the sense of carrying a hard-hitting cartridge if you can’t hit anything for fear of recoil? This is no rhetorical question. It is faced by not just teenagers, but women, small-framed men, and hulking behemoths that could anchor the Packers front line.

Before you puff up and belittle the wimps, reflect on your fear of heights, snakes, spiders, public speaking, women…consider also such things as detached retinas, rotator-cuff tears, slipped discs, and spinal injuries. Folks have good reasons for avoiding excessive recoil. But how?

We hunters have several options. Perhaps the easiest is giving up the myth of knockdown power. Arrow after arrow, bowhunters prove that everything from whitetails to elephants can be terminated with virtually no power. They clearly understand that hemorrhaging is the precursor to punching a tag. Unless their arrow hits the spinal column. Then, despite most modern broadhead-tipped arrows jumping off the bowstring with less than 100 foot-pounds of kinetic energy, the animal collapses as if, well, as if a broadhead landing with perhaps 50 foot-pounds of energy has just severed its spine.

And riflemen are concerned the 2,800 foot-pounds in a 150-grain bullet from a 7mm-08 Remington won’t have enough punch for a mule deer?

Your first step toward reducing unwelcomed recoil is to consider shooting a smaller, “lighter” cartridge. Karamojo Bell proved quite conclusively that a 173-grain, round-nose, full-metal-jacketed 7mm bullet at 2,300 fps was more than powerful enough to reach the vitals (brain) of the biggest elephants. The Scotsman flattened 800 pachyderms with the .275 Rigby, the British gunmakers’ title for the 7x57mm Mauser.

Bell collected about 200 more elephants with other “light” rifles, even a 6.5x54mm Mannlicher-Schoenauer. In addition, he shot between 600 and 700 buffalo with these and similar light cartridges. Obviously, knockdown power was not deficient when bullets were applied to the proper place.

Such surgical accuracy is often used by modern hunters as their excuse for shooting more powerful cartridges. Never mind that they and every gun writer and “expert” since Moses insist that light bullets in the right place always outperform heavy bullets in the wrong place. They insist the heavier option will save their bacon in case of poor shot placement. This becomes a self-defeating philosophy.

“I can’t shoot precisely enough to count on hitting the vital zone, so I’ll shoot a bigger cartridge that kicks so much it further decreases my chances for hitting a vital zone—even though I know a bigger bullet in the belly doesn’t work as well as a smaller bullet in the heart.”

Wait a minute, haven’t we driven past this tree before?

If you can possibly get off the power trip, do try. And then dedicate yourself to training. With less recoil, you’ll actually enjoy shooting, and that will lead to success. And that will lead to more practice, which will lead to even better shooting.

By the way, today’s bullet and ammunition manufacturers are aligned to help you.

The 7mm-08 Remington, for instance, shoots the same weight/diameter bullets Bell shot, but with 200 to 300 feet-per-second more velocity. That’s the same velocity gap, 300 fps, between the 7mm-08 and 7mm Remington Magnum.

Bullets are similarly improved. A full metal jacket is not only not recommended for deer and antelope, it isn’t even legal in most jurisdictions. But that’s okay because today’s controlled-expansion bullets, such as the Swift A-Frame, Barnes TTSX, Nosler Partition, Federal Trophy Bonded Bear Claw, Norma Kalahari and Hornady GMX, to list but a few, expand reliably like soft points, yet retain mass in a long shank like solids to drive that expanded nose deeper than any soft-nose could hope to penetrate in the old days. Quite simply, you can “up armor” with ammo to offset any perceived downsizing in caliber or velocity.

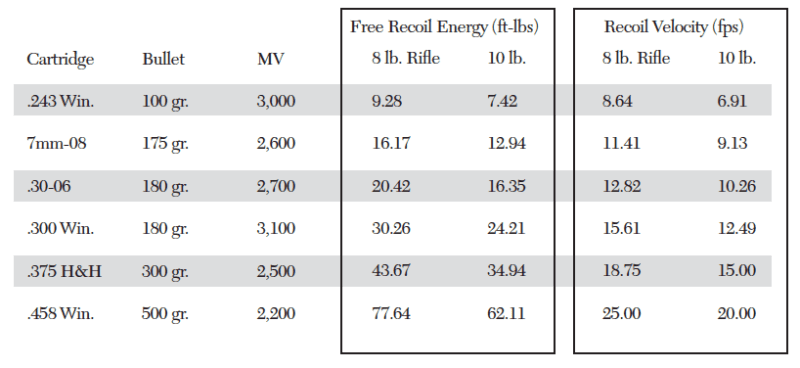

Your next option for reducing recoil is the traditional one: carry a heavy rifle. The old 8-pound standard for a .30-06 remains viable, but ten pounds will tame recoil even better. How much better? Let’s look at some rough numbers in sample cartridges below.

Of course, you have to carry the rifle, and depending on your style of hunting, how far you go and your physical capabilities, more weight might not be the ideal option, either. In which case some recoil-absorbing crutches are in order. There, I said it. No use beating around the bushes. We’re advocating the emasculating sissy pads here. If you’re not man or woman enough to handle that, then ignore this part.

As for me, I’m more than happy to enjoy the pain-ameliorating benefits of soft buttpads, raised cheekpads, wide combs, rubber combs, gel shoulder pads and stock-enclosed recoil reducers. There are mercury, tungsten, and oil/piston versions. My wife uses a tungsten short tube in her Blaser R8 .375 H&H. Her enjoyment of reduced recoil inspired me to try one in my .458 Lott R8. On safari, we happily tote the 12- and 16-ounce recoil-attenuating tubes.

My final suggestion for minimizing felt recoil and the resulting desire to flinch is mind over matter. This does not mean grin and bear it. It means progressing from dry firing to .22 rimfire firing to .243 Win. and on up the scale, all the while concentrating on gun and trigger control. When your mind is on the target, not the recoil, you shoot more precisely and, surprise, don’t feel the recoil. Think about the kick and it busts your chops. Think about the bullet curving to the heart, see it in your mind’s eye, strive to see it in real time and you’ll hardly know the rifle went off.

A great aid to this end is to have a friend load your rifle behind your back for each shot. He or she should actually hand you an unloaded rifle until you no longer flinch. You’ll know you flinched when the hammer falls on an empty chamber. Once you’re concentrating on the target and no longer anticipating the recoil, she loads a live one, the target dies and you don’t feel the recoil. Work it, baby, work it.

By the way, if and when this is working for you, move up to your heaviest rifle. Then step down to the likes of a .375 H&H or .30-06, something you used to think hit pretty hard. I’m betting it’ll feel more like a .243 Winchester. That’s the effect of mind over matter. That’s why and how some 100-pound women manhandle .375s and .416s with nary a twitch.

Recoil. It’s real. But it doesn’t have to be painful. Oh, as for that scope-eye problem? Don’t creep the stock and get a longer eye-relief scope. Go for four inches or more.

Following the success of his acclaimed books Shotguns and Shooting and More Shotguns and Shooting, Michael McIntosh continues his celebration of the shotgun in Shotguns and Shooting 3. As with his earlier volumes, the subjects covered are wide ranging, from the earliest firearms to the author’s current favorites, and from technical discussions of barrels and ejectors to shooting techniques. This book will appeal to hunting and gun enthusiasts everywhere. Buy Now

Following the success of his acclaimed books Shotguns and Shooting and More Shotguns and Shooting, Michael McIntosh continues his celebration of the shotgun in Shotguns and Shooting 3. As with his earlier volumes, the subjects covered are wide ranging, from the earliest firearms to the author’s current favorites, and from technical discussions of barrels and ejectors to shooting techniques. This book will appeal to hunting and gun enthusiasts everywhere. Buy Now