Harris-Ching is one of the handful of artists who advanced the position of wildlife painting into a serious artistic genre.

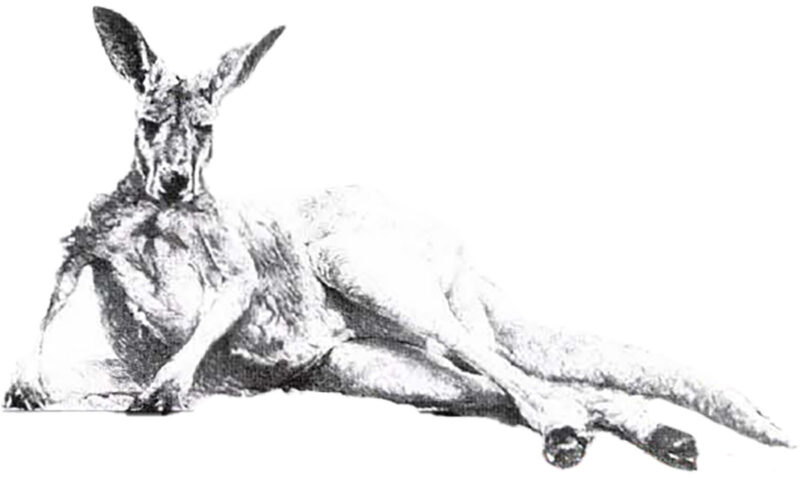

The ground is tinder dry, the air is suffocating — infuriatingly unlike air — more like the fug under a woolen blanket. Under the midday sun, the landscape is a faded watercolor, sepia where it should be green. The few trees are blackened and gaunt, victims of last year’s fires. At first there seems to be no sign of life, but then, in the shadow of a fallen log, there is a slight flicker. Straining our eyes, we see an adult kangaroo with its joey. They sit patiently, blending into the log, sheltering from the sun and waiting for the human intruders to pass by. Every now and then, they give themselves away with an ear twitch as a fly annoys, and occasionally they will be driven to take a swipe at it with a delicate paw.

The ground is tinder dry, the air is suffocating — infuriatingly unlike air — more like the fug under a woolen blanket. Under the midday sun, the landscape is a faded watercolor, sepia where it should be green. The few trees are blackened and gaunt, victims of last year’s fires. At first there seems to be no sign of life, but then, in the shadow of a fallen log, there is a slight flicker. Straining our eyes, we see an adult kangaroo with its joey. They sit patiently, blending into the log, sheltering from the sun and waiting for the human intruders to pass by. Every now and then, they give themselves away with an ear twitch as a fly annoys, and occasionally they will be driven to take a swipe at it with a delicate paw.

The human intruders move closer. The mother casts startled, doe-like eyes in our direction and then, with the grace of a slow-motion movie sequence, leaps up and away, followed immediately by her young. They bound in huge arcs across the Australian landscape, looking as if they have springs instead of limbs.

Ray Harris-Ching is thrilled by the sight. This is what he has travelled 12,000 miles to see, and it never fails to delight him.

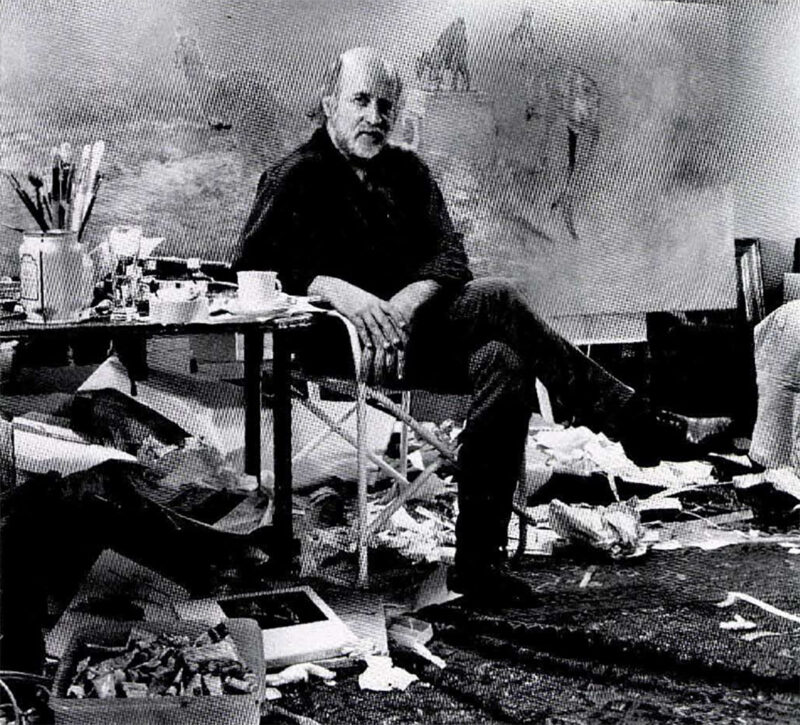

Harris-Ching in his Australia studio.

You have to be in love with Australia to stand out in the midday sun in such a barren place, many miles from human habitation — no nearby stores, no petrol stations, no help if the car breaks down. Although this is only the border of Victoria — the smallest state and nowhere near the interior — it’s still the outback and very desolate.

We get in the car and drive off slowly along the dusty road, air-conditioning turned up high, straining our eyes for signs of life. Suddenly, an adult emu and five chicks run across the road, heads lunging madly back and forward as their great legs pound furiously over the land. The adult is probably the father, who will hatch a brood of eggs, each from different mothers and take charge of the young when they appear.

Ray leaps out of the car and runs into the undergrowth for a better view, training binoculars on them until they disappear. He comes back, boots, jeans and socks covered in burrs — like great fluffy snow boots — innocently amusing. But they are one of Australia’s poisonous grasses, and later that night, we discover they have worked their way into his feet and ankles. It will be months before the red welts stop itching.

Oil painting of muntjaks, small antelope native to southeastern Asia and the East Indies.

We drive on, scrutinizing a line of trees, slowing the car to look up into the branches. A bulge on a high branch — like a grey epiphyte — slowly transforms itself into a koala, lazily looking down at us. He perches on the most ridiculously small twig, front paws wrapped around the bough in front, swaying unconcernedly in the breeze. The sight of us bores him; he turns away.

We see another bulge: a mother with sleeping young clamped to her back. The mother is slowly chewing a eucalyptus leaf and the end of it sticks out of her mouth like a cigarette. Ray sketches for a half hour or so. Eucalyptus oils supposedly have a soporific effect on the animals, keeping them permanently ‘stoned’. Whether it is this, or the heat, they are not averse to posing for hours and even, as if to oblige the artist, slowly adopting a new pose from time to time. We move off, feeling quite as lethargic as the koala.

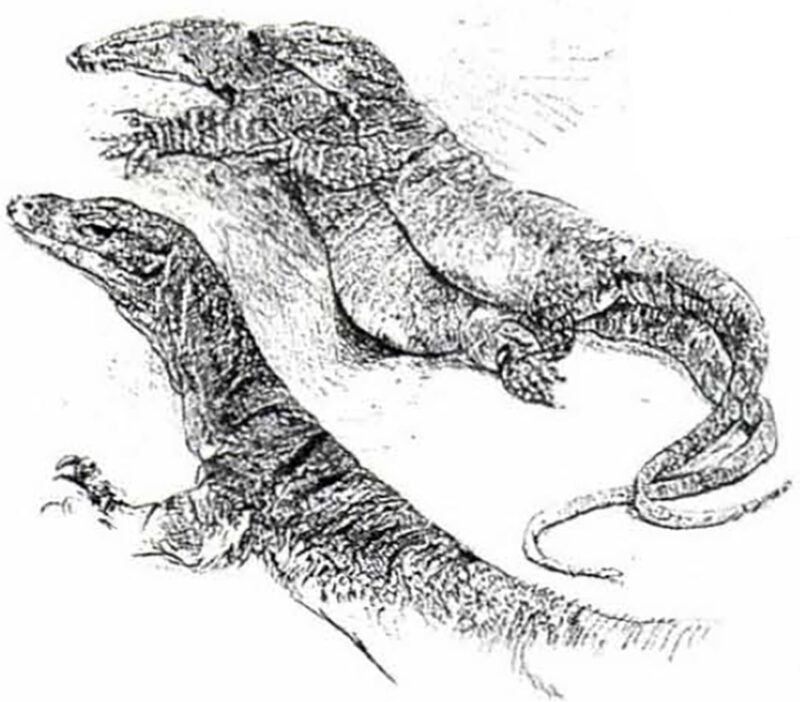

Towards us on the road, running with a desperate waddle, a huge goanna, tail whipping from side to side, streaks across in front of the car and up a tree. Amazingly, his beautiful, bright markings of yellow and black blend into the pattern of dappled sunlight and he disappears on the branch. But we get out and look closer; he sits rock-still, cold, reptilian eye taking in our every movement, ready to dash up higher if we get too close. Again Ray gets out the sketching pad and the exotic creature takes shape in pencil on paper.

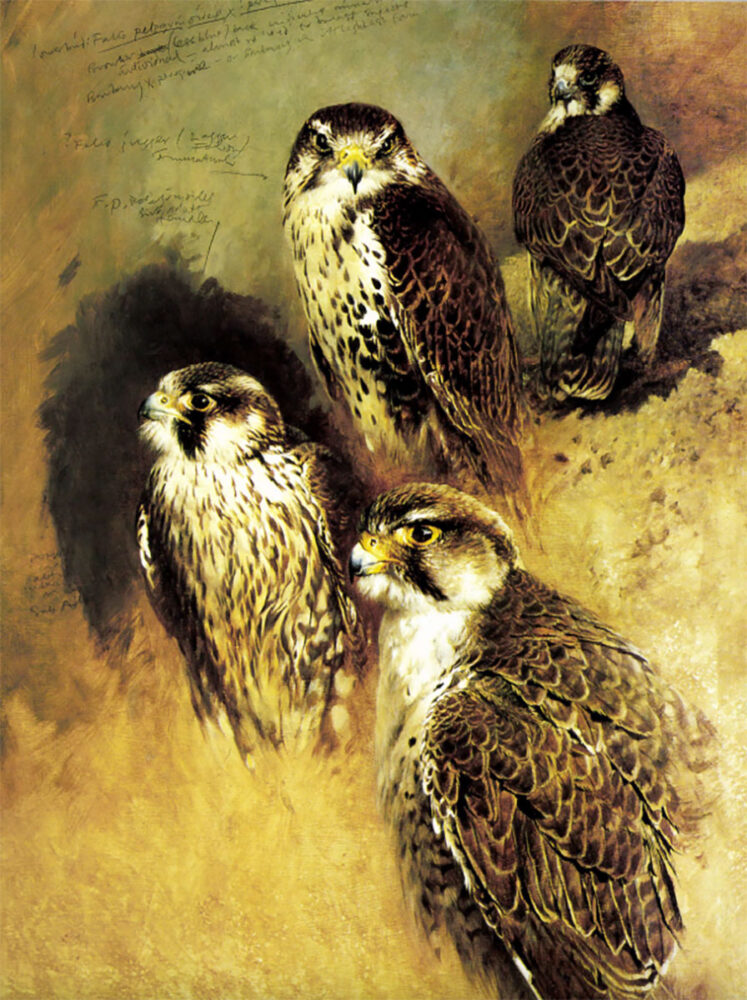

Oil study of desert falcons.

A wedgetail eagle floats high overhead, harassed by half a dozen magpies. The heat is now extreme. Every movement is an effort. We are bathed in streams of perspiration. A hot wind springs up, and flies persecute us constantly. It seems madness to persist with this torturous trip. What brings an out-of-condition man, who has no interest in sport and does not much care for the great outdoors, to this place and to this pursuit? Why has he been suddenly transformed into an intrepid tracker?

It was his first confrontation with a kangaroo in the wild that did it. Ray had seen them at zoos and wildlife parks and thought them very beautiful — but that first time in the wild, when he walked up a grassy rise and just over the brow came face to face with a large eastern grey kangaroo, looking at him with calm curiosity, made an unforgettable impact. Memory of the moment still holds the same excitement for Harris-Ching. It haunted him, back in England, causing him to lay down his brushes, put aside the paintings of birds for which he is so well known and get on a plane again, in pursuit of the kangaroo images that had been forming in his mind since that first encounter.

Harris-Ching is one of those rare painters whose work is sought-after internationally by a select number of collectors, who simply fall under the spell of his art. He is best known for his animal art, but his pictures are often bought by people with no interest in wildlife art.

Harris-Ching’s colorful oil painting of a plate-billed

mountain toucan.

It is difficult, looking at his paintings, to place them in time or space. The thinly painted oil surface of his work refers perhaps, to the 19th century Pre-Raphaelites, whom he admits have been his greatest influence. But the subject matter and the passion with which he creates the images can only be of 20th century origin, conceived and produced at a time when the world is becoming deeply concerned with the subject of wild animals.

His coming to wildlife art, however, was not through conservation or sporting traditions. When Ray first began painting birds in the mid-60s in New Zealand, there was no such thing as wildlife art. Since the decline of the great Victorian animal painters, wildlife had not been a subject for serious art. While a great admirer of illustrators such as Kuelemans and Wolf, he had neither the temperament nor the inclination to be that sort of artist.

In Studies & Sketches of a Bird Painter, he says: “In such [illustrative] work the artist must represent the entire species by a single bird. There is no attempt to show individuality; the information supplied is rather like a map: simply the placement of color and pattern for correct identification. For my own work, I am not able to resist carrying the painting further and to say something, also, about the character of the individual bird.”

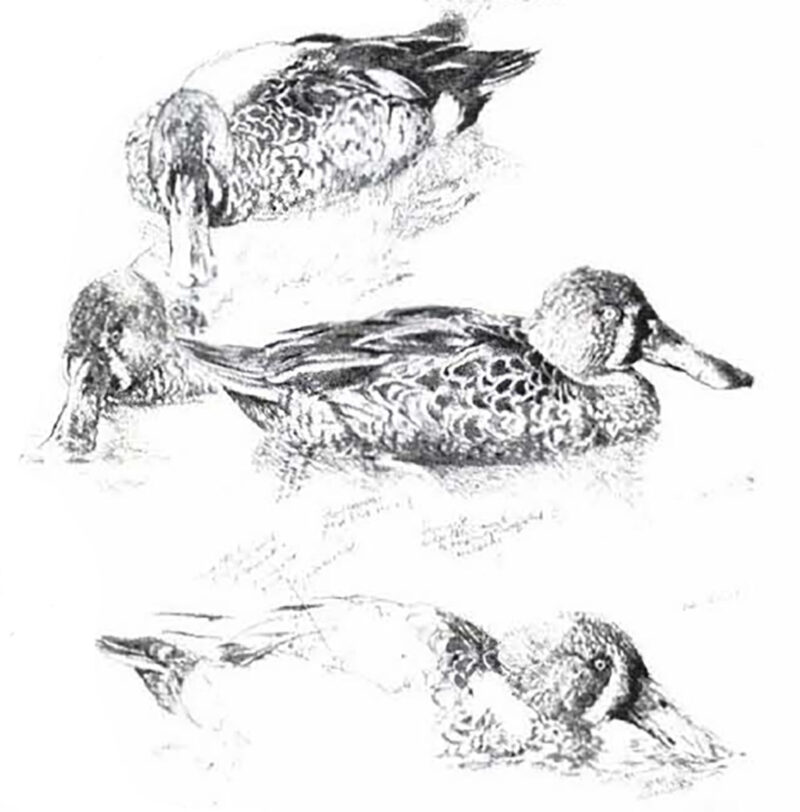

Eclipse Pochard.

Paradoxically, he has illustrated one of the major bird books of the 20th century, The Book of British Birds, which in Europe has sold in its millions and has been translated into 11 languages. But the characteristically eccentric illustrations which dazzled the public when it was published in 1969, turning it into a best seller overnight, are not those of an illustrator — they are inimitably Harris-Ching bird portraits.

Since then, several books have been published on his work, showing the evolution of an artist’s style. The latest, Ray Harris-Ching in the Masters of the Wild series published by Briar Patch Press, traces the changes in medium and technique from his early, meticulously detailed watercolors to his most recent oils.

Harris-Ching is one of the handful of artists working today who have advanced the position of wildlife painting into a serious artistic genre. In a field that veers often towards conservationist or commercial interests, his paintings are pure artistic statements. Although he is as concerned as the next man about the harm we are doing to our earth, Harris-Ching believes that the power of art is as art. It must have its own reasons for being — its own integrity — otherwise it will be consigned to the dustbin of history. “Art can, of course, make us sensitive to environmental matters, but if that is its first concern, then it will not be significant art.”

Pencil drawing of New Zealand shovelers.

He takes no notice of market demands. The people at The Tryon Gallery in London, who have been his dealers for the last 20 years, have long given up trying to persuade him to fulfill the many commissions and requests they receive for him to paint this bird or that mammal. Ray paints only what he is consumed with — and at the moment it’s kangaroos — regardless of the fact that there is probably little or no demand for the subject as a painting.

In England, where he has lived on and off for most of his adult life and is so well known for his paintings of birds, he has produced a gloriously individual body of work. His paintings of familiar birds, such as Kestrel on the Sack and The Partridges sunning and dusting and Winter Wrens are landmarks in wildlife painting, establishing a style and an approach unmistakably his own. Usually the species portrayed is a commonplace one.

“These familiar birds carry no bold and violent color and are entirely suited to my personal preferences. There is a simple sense and logic about the patterning of a sparrow or blackbird, to which I am able to return over and again, without any loss of fascination. For the painter of birds working in this half of the 20th century, even the most remote parts of the world can be reached easily … and … the camera can gather valuable information quickly. But with it comes a less valuable side, for the weakness of photography as a source of reference is that it never can allow the excitement of personal confrontation with the bird as an object, at the moment of painting … One may have no special or particular desire ever to paint this bird or that, or even, say, a blade of grass — until such a thing is at hand, closely looked at, seen, perceived — then in a very short while, there may benothing one wants more than to paint it.”

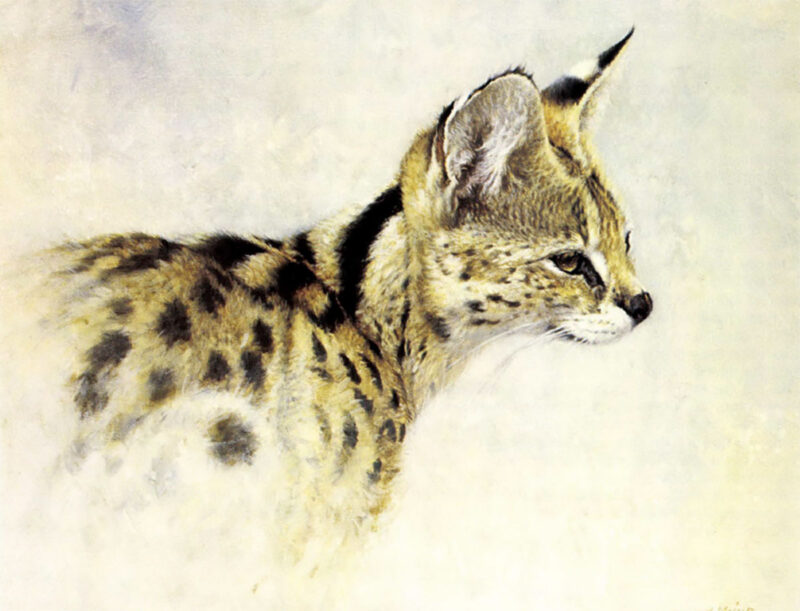

Serval, a small spotted cat of Africa’s Serengeti.

Drawing is the foundation of Harris-Ching’s art. His best, his most creative work, comes when he is looking most intently at what he is drawing. It is the “excitement of a real encounter with the subject,” he believes, that gives power to an artist’s work and “… the discipline of close observation … his own vision of the thing … [is one of the few ways] for the painter to be sure that the image he has made is really his own. For no matter how he strives to duplicate nature, the individuality of interpretation will be dramatic and the paintings quite startling in their variation. For if two skilled artists paint a sparrow … the bird is the same, yet the paintings are different — the difference must be in themselves.”

An artist’s deepest inspiration always draws on his roots. Born in New Zealand — Australia’s closest neighbor, but a country without any native mammals — images of kangaroos and koalas and kookaburras were part of his childhood. A longing for the sights and sounds of Down-Under has plagued him at regular intervals, bringing him back at first to New Zealand, but more frequently in recent years to Australia.

Permanently an amalgam of the here-today-gone-tomorrow cycle of fire and flood — where landmarks can disappear in a few moments and landscapes can be astoundingly changed and thus be irrevocably the same — Australia is a challenge to any artist. The knowledge that any particular tree that one grows to love for its shape and silhouette on the skyline, may, tomorrow, be a pile of ash, leaves its own mark. The temptation might be to paint the animals and landscape in general terms; if that tree will disappear tomorrow, any tree will serve as a symbol; if that kangaroo will be dead tomorrow, any kangaroo will suffice. But it is Harris-Ching’s need to see and paint the individual animal that gives him the impetus to keep on painting.

Drawing of goannas.

In a country where regeneration from the worst scourges of nature seem miraculous, the kangaroo’s unique system of reproduction is symbolic of the wonder and tragedy of this land. The females hold a ‘quiescent embryo’ constantly in the womb, which can be born the moment conditions are favorable. The animal is continually slaughtered as vermin by farmers, and yet its populations remain more or less stable.

Harris-Ching finds the beauty and innocence and strength of the animal compellingly representative of Australia, and yet it is not enough to paint it symbolically; he must see individuals to want to paint the kangaroo at all.

He recognizes that next year or the year after he may have exhausted his need to paint Australian animals, but at the moment, the studio in the apartment he has bought in Melbourne is filled with paintings of kangaroos, all in various stages of completion, Delicate drawings and canvases large and small line the walls, some showing family groups — mobs, as they are called — lying about in clusters that are wonderfully sculptural. Others show the animal speeding over the ground, almost a blur in the harsh landscape of red clay. Some show kangaroos grooming, their strange limbs taking on improbable lines and angles, standing on their haunches, scratching with their disproportionately small front paws, quite unlike the usual stance of four-footed beasts.

Watercolor of sleeping barn owl.

Until Harris-Ching began painting the kangaroo, no painter this century had taken the animal seriously, as a subject for art — a consequence, perhaps, of a lack of any real hunting tradition in Australia and the sporting art that always emerges from it. (The animal, incidentally, is reputed to be excellent game, and its meat unusually low in cholesterol.) Whether these paintings and drawings will stay in Australia is as yet, unknown — already the first few have been sold in England — some to Australians living there, but surprisingly, some to people with no connection to this country. “It’s a measure of the power of the image of this animal,” says the artist.

Come late afternoon, as the sun is setting, the faded landscape is transformed: astounding colors are revealed — oranges, pinks, mauves — the earth and its plants glow and scintillate as rich, golden light brings them to life in glorious technicolor. Brilliantly marked parrots appear, waking up from the hollow logs and shady branches where they have slept through the heat of the day. Bright-beaked finches flock in the sunlit trees, dashing and flashing in the last lingering rays; swallows and bee-eaters, like speeding jewels, dip and dive over the nearest waterhole to feast on insects that have come out of hiding.

It is easy to understand why a painter would be fascinated by this strange, unearthly part of our planet and why Ray Harris-Ching would want to add its images to those of the other wild creatures he has painted and drawn, so dazzlingly, all over the world.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now