To elicit thoughtful reflection … to trigger an emotional response, these are the things McKissick seeks in his art.

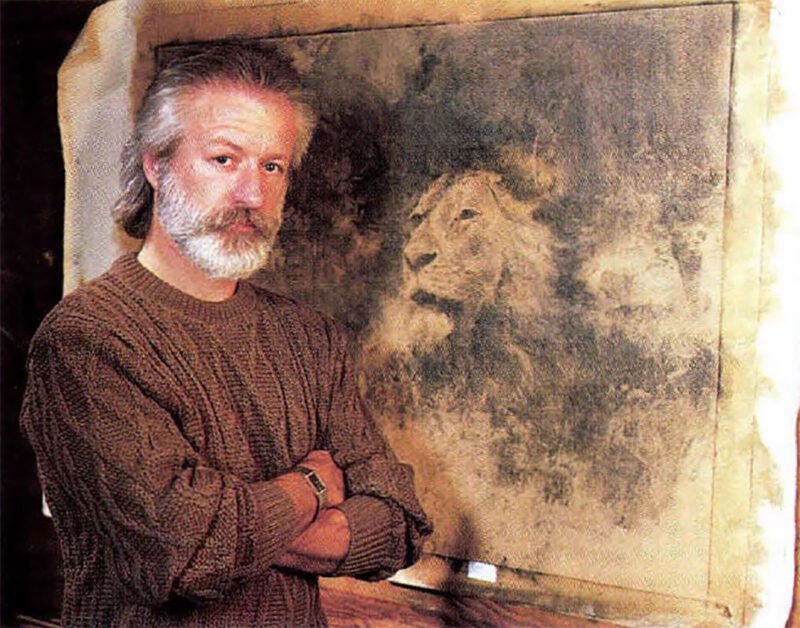

Of course you can’t always tell a book by its cover — nor a painter by his paintings. Take Randall McKissick, for example. With just a casual glance, you’d think his impressionistic paintings were completed in a single sitting, alI a prima, the artist wielding his paintbrush like a rapier across the canvas. But that’s not the case, and it’s not the man.

If you could spend even a few minutes in McKissick’s spacious studio on the banks of South Carolina’s Congaree River, you’d understand that the spontaneity in his paintings of fish and wildlife is in reality premeditated, the result of a long, exacting and often exhausting process that only a perfectionist like McKissick is willing to endure. It begins with an idea or concept that he mulls over and refines in his mind for weeks or even months. Then comes hours of studying his subject in books and videos or observing the animal firsthand. Finally, standing barefoot at his easel, McKissick begins to paint, working quickly but pausing constantly to agonize and reflect on what he’s put down. Quite often, he will spend more time thinking about the piece than he does actually painting it, a procedure that might continue for days until the scene at last matches his original idea.

If you could spend even a few minutes in McKissick’s spacious studio on the banks of South Carolina’s Congaree River, you’d understand that the spontaneity in his paintings of fish and wildlife is in reality premeditated, the result of a long, exacting and often exhausting process that only a perfectionist like McKissick is willing to endure. It begins with an idea or concept that he mulls over and refines in his mind for weeks or even months. Then comes hours of studying his subject in books and videos or observing the animal firsthand. Finally, standing barefoot at his easel, McKissick begins to paint, working quickly but pausing constantly to agonize and reflect on what he’s put down. Quite often, he will spend more time thinking about the piece than he does actually painting it, a procedure that might continue for days until the scene at last matches his original idea.

“My good friend Gordon (Smith) was in the studio one day and heard me cussing and throwing my brushes,” McKissick recalls. “He walked over and said, ‘Gee, I guess painting isn’t a therapy for you.’ And he’s right — it’s quite an agonizing thing for me. It seems that I’m always after something and the frustrating part is getting it.”

Indeed, the lively, impressionistic quality in McKissick’s art suggests a rapid, spontaneous execution. But that’s deceptive considering that he builds each painting slowly and deliberately “to get things just right.”

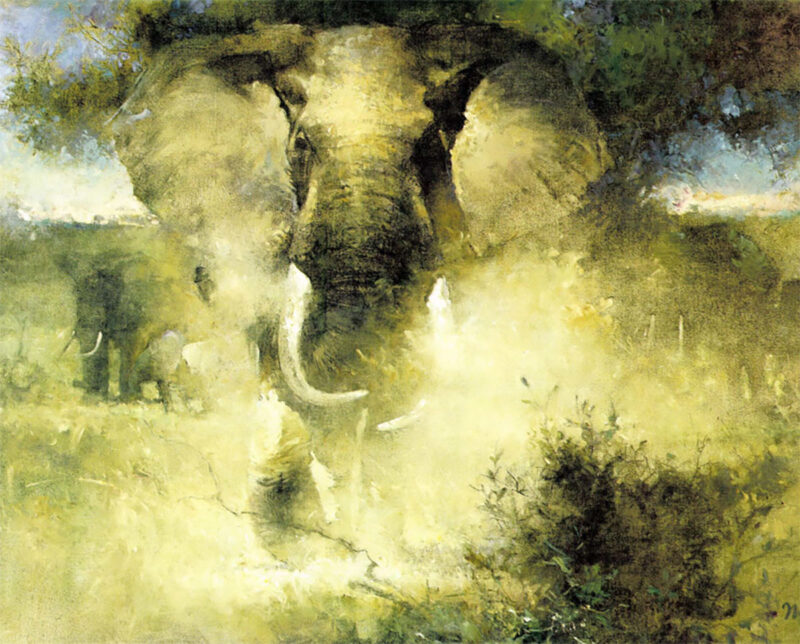

The artist used a low perspective and a pall of swirling dust to heighten the drama in A Called Bluff.

“Rarely do I do anything more than a quick and dirty thumbnail sketch, because I know the painting is going to change,” he admits. “As I work, I become more and more educated as to what I’m doing. The paintings that flow the best are those where I know more about the subject. I did a kudu piece several years ago, and I spent a lot of time researching them so I could capture that elusive quality of bull kudu. I hate guessing at something. Though my work is loose and painterly, any flaws in an animal’s form and gesture will show up quickly.”

Perfectionist’s mind, impressionist’s hand. So how would an artist come to have such obviously conflicting traits? Perhaps it was so at birth — on August 12, 1946, in Columbia, South Carolina, where he’s lived most of his life. Or maybe it started in first grade, when McKissick’s tempera painting of a circus clown won a blue ribbon at his elementary school. Or after high school, at Ringling School of Art in Sarasota, Florida, where he studied under a prestigious Hallmark Scholarship.

Most likely, McKissick’s penchant for perfection grew during his 25 years as a commercial artist, because he was never given enough time to finish his illustrations exactly like he wanted to.

McKissick cuts his canvases to sizes that complement his subjects, in this case a narrow shape for Jaruco Blue.

After graduating with honors from Ringling in 1970, McKissick joined a graphics art company in Charlotte, then, two years later, started his own commercial studio. Even if you’re loaded with talent and move to New York or Los Angeles, it’s difficult for a young illustrator to crack the big advertising agencies. And if you live in a small city in the South, it can be next to impossible. But that’s exactly what McKissick achieved, and within a few short years.

Today, Randall McKissick is a familiar name to many of the nation’s top advertising execs. Over the past 20 years he’s done illustrations for some of America’s biggest corporations, including Coca Cola, McDonalds, AT&T, American Express, Wrangler, Georgia Pacific, Universal Pictures and the Boy Scouts of America, to name but a few. His illustrations have appeared in countless catalogues, magazines and books, on Manhattan billboards, and on product packaging of every size and description.

In Tandala he captures the “now you see him, now you don’t” nature of bull kudu.

There have been other talented artists who eventually left the hectic, fast-paced world of commercial illustration to paint wildlife and sporting art. Bob Kuhn, Robert Abbett and Jack Cowan — all grew weary of the onerous demands and deadlines of fickle art directors. What most irritated McKissick were the deadlines. “Commercial illustration always involves a certain amount of compromise,” he says. “But I especially dislike having to let something go before it’s as good as I can make it. I put out a lot of junk years ago that I thought could have been better. But what can you do when they only give you a few hours before Fed X is knocking on the door.”

Ironically, it was an illustration for a tiny South Carolina company that became the first steppingstone toward a new career. In 1990 McKissick created a stunning portrait of a blue marlin for Mount Pleasant Seafood in the historic sea-coast city of Charleston. A friend of McKissick’s published the image in limited edition, and the staff at the International Game Fish Association liked the prints so well they began selling them to their membership.

Although he still accepts a few commercial art jobs to help pay the bills, McKissick now spends most of his studio time painting the earth’s wild creatures — from elephants and leopards of the African highlands to marlin of the deep blue Pacific. And he’s doing it in a style that’s unique among animal artists.

“I like painting styles that are obviously different,” says Gordon Smith, who owns American Heritage Gallery in Columbia. “I like to walk into a show and not have to read the names on each piece to see who did them.

“Randall’s style is not nearly as literal as all the other wildlife artists; it’s much more impressionistic, which I think shows a lot more thought and talent. I’m not sure his style appeals to the masses, but I’m sure it does to people who have developed their own personal eye, whether they know it or not.

An array of luminous colors dazzle the eye In Playing for Time.

“It is indeed true that most contemporary wildlife artists put details of the animal ahead of the animal itself and the artist’s relationship to it. They show much more detail than the human eye can ever absorb. Their works are not paintings, as such, but technical renderings.

“I’m more interested in an impression or mood rather than creating eye lashes and fine hairs,” McKissick explains. “I want something that’s spontaneous, with a sense of openness and freedom.” McKissick creates his spirited paintings by using luminous colors and applying the paint in broad, fluent brushstrokes that make a dramatic statement about the animal.

He usually works his oils wet-on-wet, often mixing the paint right on the canvas, and then drawing with it to create varied edges and subtleties in hue and value that heighten both depth and interest in the scene.

Closing In shows a cheetah and springbok, their blurred forms appearing as if we were actually witnessing the life-and-death drama.

It has been said of the great 19th-century French impressionists that they painted not nature as it is, as the mind of the scientist would conceive it, but nature as it appears to us, nature as light and atmosphere create it for our eyes. They sought to capture a fleeting visual impression of a landscape, not make a factual report on it.

To me, McKissick’s paintings of African wildlife evoke strong memories of my own safari days, reminding me of its dusty plains and thorny woodlands. In his paintings, whether it’s a leopard slipping through tawny grasses or the mirage-distorted forms of zebras at a waterhole, the animals and foliage are rendered in a closely coordinated range of values, a harmony of gray and green and ochre that convey warm and even light and a transparent atmosphere — all trademarks of wild Africa. But in his scenes of marlin, sailfish and other big-water denizens, McKissick unveils a far richer palette. “Capturing the refraction of light, the abstract way it wraps around the fish, and the sparkle of light in the water, these are the things I’m after.”

In Jaruco Blue, for example, McKissick laid down fairly abstract color next to the realistic form of the fish. And so, what appear to be random brushstrokes suddenly become something very real.

McKissick often depicts predators in a moment of tension, such as this riveting portrayal of a leopard stalking its prey.

“The abstract always interests me,” says McKissick. “But at this point in my career, income is still a concern so I have to be more specific in some cases — to tailor the image for the audience more than I would normally.”

Still, McKissick will always think differently than the vast majority of wildlife artists, even to the shapes of his canvases. He typically cuts out a piece of canvas so it “feels right” for the image he has in mind, then staples it onto his easel. “For some reason, very horizontal pieces feel good to me, especially for fish like marlin and trout, because they profile their shape. A horizontal format also works well for African wildlife, because it enables me to create a more panoramic view. Rarely do I do vertical pieces, and I never work in the standard sizes and shapes. When the painting’s done, I just take it off the easel, roll it up and mail it to the buyer.”

To elicit thoughtful reflection … to trigger an emotional response, these are the things McKissick seeks in his art. He catches our eye by depicting a wild animal caught in a moment of tension. But as you look at the painting, or more accurately, into it, you see more and more, and slowly you find yourself part of the scene.

The artist created this portrait of Robert Ruark for our Lost Classics book on the legendary writer.

“I consider myself an emotional person, and I hope that comes out in a spontaneous way. Several years ago, I did a painting of a cheetah chasing a springbok, and I was as much interested in the panic on the gazelle’s face as anything else. It was an emotional thing that I wanted the viewer to pick up on.

“Now I’m mulling over another idea — about doing lions or some other big predators after they’ve made their kill. There’s something about the bloody muzzle of a lion and the finality of the kill that interests me esthetically. I guess the reason I haven’t done it is that I feel uncomfortable about it, yet I find myself wanting to convey that uncomfortable feeling.”

While he realizes that wildlife art is no longer the money tree it once was, McKissick is committed to painting wild animals “simply because I care about them … about the miracle of life. There is-something about wild animals — their beauty, their spirit — that I think we underestimate or just disregard. I also think they have an intelligence that we haven’t begun to understand. Unfortunately, we tend to realize how wonderful something is only after it’s gone.”

And so, Randall McKissick will continue to bring us his fresh and powerful statements — lasting impressions that touch us emotionally, stirring something deep within all of us.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now