A painter he is, and that’s what he always wanted to be…

His house is what realtors, in Salisbury, Maryland, call a two-story “Colonial.” It sits near the back of a tasteful subdivision — meaning one where developers have left standing the native loblolly pine, oak and holly — among similar houses of intensely manicured lawns. Well maintained, the house fairly glistens, beneficiary of a great deal of tasteful and detailed attention. I wonder: Is this the house of Wil Gobble, wildlife artist?

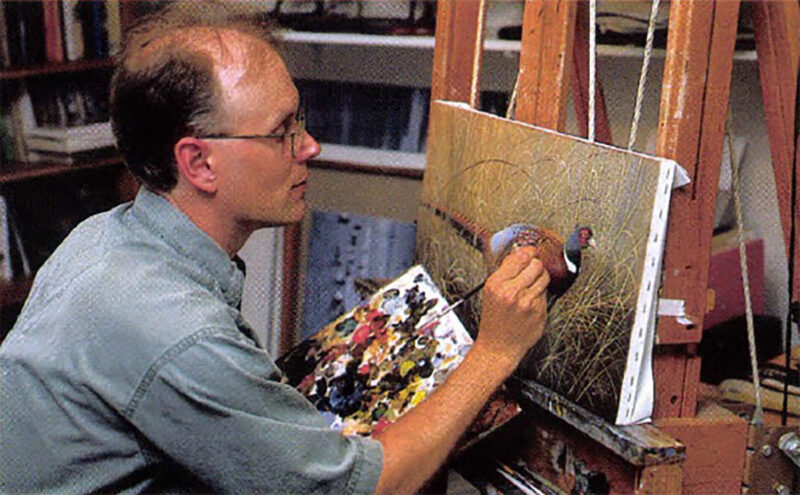

The artist at work.

He and Chris, his wife, open the door, immediately apologizing for the clutter in the room to the right, a happy jumble of flowered, inflatable chairs and toys strewn on a braid rug. “That will be the living room,” Chris says with an unspoken “someday” lingering at the end of her sentence. Wil laughs, “You know, the kids…” He’s referring to daughters Kimberly, 10, and Pamela, 6, who’ve been exiled for the day to their grandparents’ house. “Otherwise, It’d be chaos!” Wil says with more self-effacing laughter.

The walls carry the works of this artist who’s recognized as one of the most competent among those who portray wildlife. “Mostly prints,” Wil says. “I don’t have many originals.” We climb the stairs to his studio over the garage. Here the painter rules.

Light flows from the left across the stool where he sits next to a canvas — this one of a buck and doe in a cornfield with a string of turkeys sneaking past — propped on the easel. Other canvases are stacked against the wall. A tiny flock of stuffed turkeys crowd the top of a cabinet. Grouse in various poses huddle on a bookcase. Other mounts of ducks and woodcock and fish fill the walls, climbing toward the peak of the dormer.

“I don’t want my work to look like a photograph,” he states adamantly. “I paint what I see — the color, the composition, the lighting.”

These are Wil’s birds, harvested Audubon-like. He did the taxidermy himself so he can study them. “When I get stuck, I’ll wait until the light is right, take a bird outside, turn it and watch what happens.” It is this attention to the subtleties of color, texture and form that have made Wil’s art so desirable. But it’s more than that.

“Wil does what he knows best — gamebirds,” says Ron Kobli, owner of Decoys and Wildlife Gallery in Frenchtown, New Jersey. Ron has carried Wil’s paintings for a number of years, and, in fact, introduced Wil to shotgun sports. “He puts a lot of effort into everything he paints, and his work is very consistent and very good. I don’t think we’ve seen the best of him yet.”

When he won the 1996-97 Federal Duck Stamp, Wil struck a mother load, though for almost 18 months afterwards he was too busy with appearances and collateral projects to paint. The following year, he was named Ducks Unlimited’s International Artist of the year. His work has been published in more than a dozen magazines including National Wildlife, Outdoor Life and, of course, Sporting Classics. He’s an invited participant at most major exhibitions of wildlife art in the East and Midwest, and for the last decade his work has graced state stamps for fishing or hunting. Wil’s paintings are part of the permanent collections of the National Wildlife Federation und are sought after by conservation organizations for their fund-raising editions. In August the National Wild Turkey Federation saluted Wil as their Artist of the Year.

Morning Caller was the “Turn of the Century Print” for the Wild Turkey. Federation.

We’ve adjourned from Wil’s studio to a table under an umbrella on the patio behind the house. A grassy path leads into a vest-pocket-sized woodland where azalea and laurel fledge beneath a canopy of oak and pine. Deer and turkey and pileated woodpeckers make cameo appearances among a woodland cast that includes songbirds, squirrels and a pair of chipmunks named ‘Chip’ and ‘Dale’ by Kim and Pam. Beyond the woods lies a farm of 200 acres of so, pasture grasses green and ready to be grazed by cattle.

Wil continues our conversation: ”To be a professional artist today, you have to be a businessman.” His images are licensed to a number of companies including Hallmark Greeting Cards, The Canadian Wildlife Federation, National Audubon Society and Applejack Limited Editions. It’s clear that Wil is as serious about his bottom line as his brushstrokes on canvas. There’s no doubting Wil’s commitment to painting. “It’s hard work. Most don’t see the blood and sweat that goes into it,” he laments. And then he laughs again, admitting that unless he’s going turkey or duck hunting, he never gets up early. “I’m in the studio by 8:30 or 9 and done by 5, when the girls are home from school. After dinner, I may go up and stare at the painting, studying it to see what needs to be done.”

On any given day, he’ll work on three to six canvases, a practice in part dictated by his medium — oil — and in part because that’s the way his mind works. “Some artists start one painting and work on it until it’s complete.” Adding highlights to dried grasses on the painting of a pheasant sneaking through the stubble, the shadows that define the texture of a feather, Wil moves from painting to painting in a production process with enough variety to keep him refreshed.

He typically completes 20 to 25 canvases a year. Yet they don’t roll off the easel one after another. “They seem to finish in bunches,” he says. “For three months, jeez, it seems like nothing happens. Then Boom! They’re done!”

Rooster pheasants fight for territorial rights in Ringneck Rivalry.

Over the years, Wil has tried many media — oils, acrylics, watercolor — but he keeps coming back to oil. “They have a rich, juicy look to them. I call play with them a little more. I can manipulate them like watercolors or use them right out of the tube, thick, when I need texture,” Though his Federal duck stamp, a pair of surf scoters winging past Barnegat Light on New Jersey’s barrier islands, was painted on art board, he much prefers “the bounce” of canvas.

A painter he is, and that’s what he always wanted to be from those days in Middlebush, New Jersey, a hamlet not far from Somerset and the industrial corridor that runs from Newark to Camden. “I don’t know when I began,” he says looking off into the fringe of woods behind the patio.” Maybe around 9 or 10 — if you have any artistic skills, that’s when you start to develop them.

“I’d always had this interest in birds and animals — we always had pets — and right behind the house in the small town where we lived there were fields and woods and everything,” his eyes brighten with the memory. “I could roam to my heart ‘s delight.” “Now,” he adds with obvious sadness, “it’s all housing developments. It’s gone. That’s one of the reasons Chris and I moved here. We wanted the girls to experience what I did growing up. This is fairly close.

“I drew in high school,” Wil continues, “but I never took a single art course. Although my parents encouraged me — they bought me paper and paints, whatever I needed — there was that underlying reality that becoming an artist was something you just didn’t do.” Wil’s father’s experiences might have added to that unspoken reality. He was trained as a horticulturist and loved working outside until illness forced him into a tool-and-die shop in Plainfield, New Jersey.

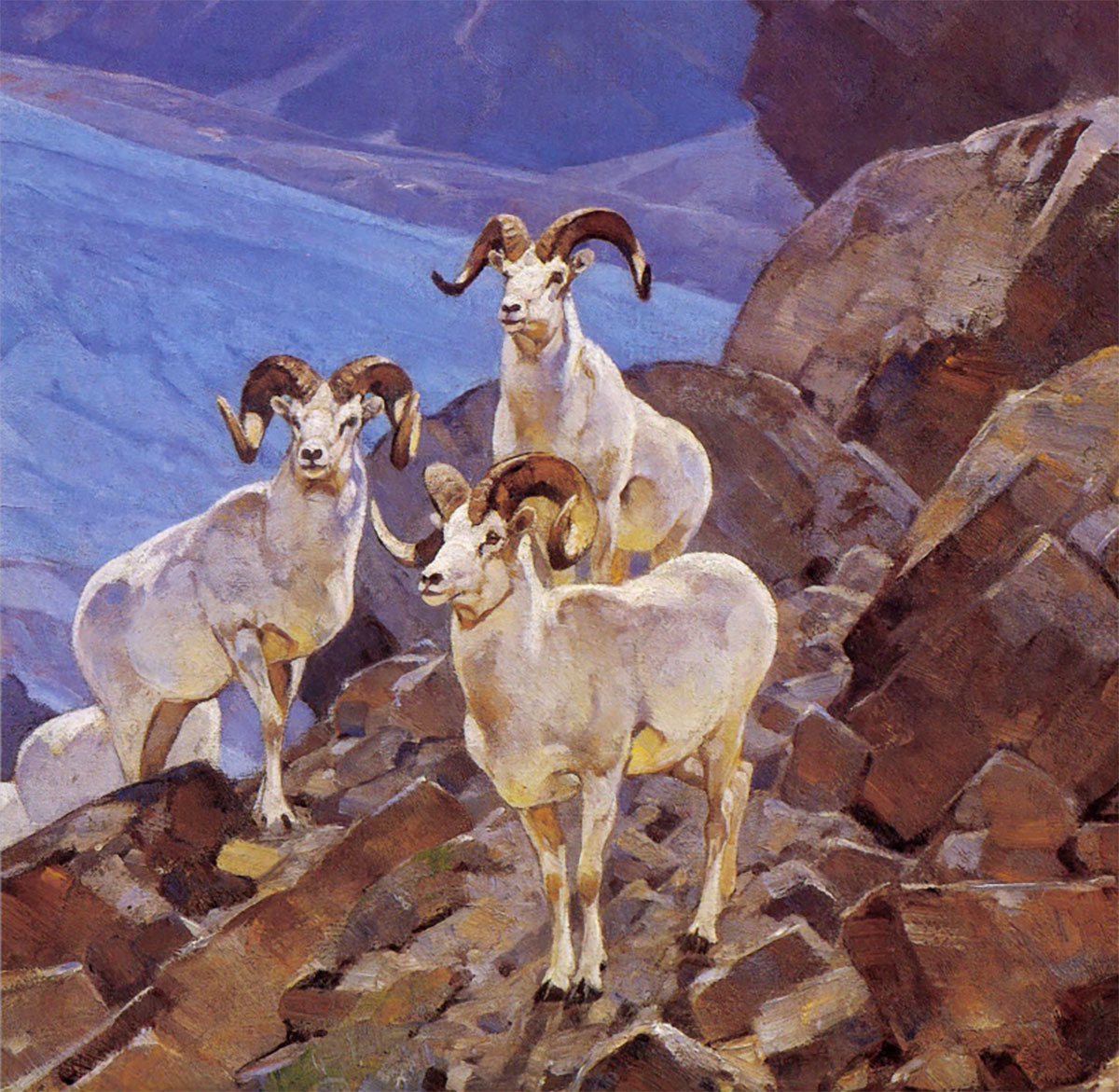

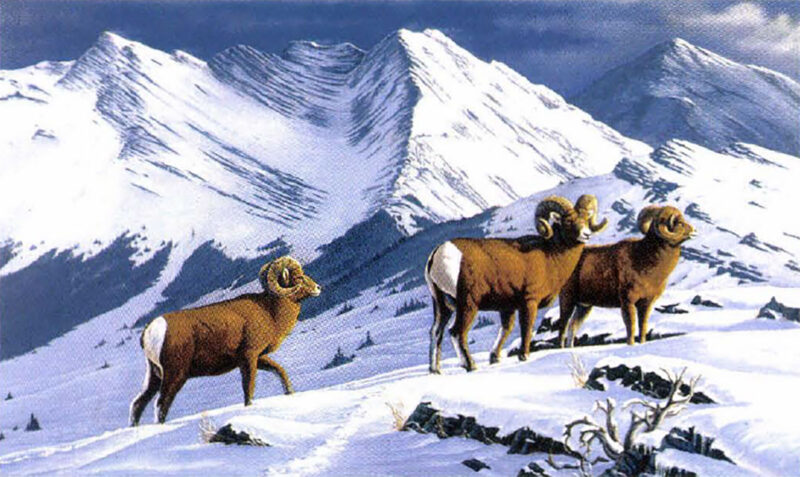

High Country Rams – Bighorn Sheep.

Cornell with its famed ornithology program beckoned Wil, but the size of that upstate New York university seemed too confining. So the fledgling artist went over the hill to Ithaca where he majored in biology and minored in art “to get away from all this science. I was crunching numbers. There was calculus and physics and organic chemistry — all that wonderful stuff I never even use today — and I was headed for a career in microbiology working with bacteria and vims for heaven’s sake!”

In that caldron of Wil’s mind kept bubbling the dream of making a living as a professional artist. It was in the Ithaca area that Louis Agassiz Fuertes, one of the great painters of birds, maintained his studio. Fuertes was a member of an expedition to Alaska that included John Muir. Fuertes’ works were featured in Song Birds and Waterfowl (1897) and on cards inserted in boxes of Arm & Hammer baking soda. Though he died in 1927, Fuertes had a powerful influence on Wil.

“Fuertes really captured the likeness of a bird. You look at Audubon’s work, and it’s a bit stylized,” Wil says. “Fuertes’ art has a liveliness to it, a ring of truth; it looked like it could flush off the page. If I could paint birds like that the rest of my life, it would be fantastic.” From the way Wil’s woodcock nestles among the leaves, ready to flush at the first footfall, it’s obvious there’s more than just a bit of Fuertes in Wil’s brush.

“I heard about all my other classmates going on to be attorneys and doctors and all this stuff,” he grins, “and here I am with this ambition in the back of my mind to be a bird painter!” He told himself that wildlife was a dream, a diversion from the precise world of a scientist. But painting kept intruding and finally he sought out Don Richard Eckelberry, the noted painter of birds who lived on Long Island before he died.

In Don’s obituary in tile New York Times, Les Line, former editor of Audubon Magazine, was quoted as saying that Eckelberry’s paintings “really breathed life,” unlike those of the 1970s and 1980s. Then photo-like detail was in vogue, and Don didn’t think much of it. He became Wil’s mentor, offering tips on style and technique and always reminding him that, if he indeed felt an all-consuming drive to paint, he should forgo microbiology and concentrate on painting.

Upon graduation from Ithaca, Wil holed up in New Jersey churning out paintings and illustrations, giving away his work for just enough to keep a little paint on his palette. Publications and exhibitions began to come. Millpond Press brought out his first prints in 1985 and slowly, oh so slowly, he made his way.

In 1993, Wil met Ron Kobli, who has also played a pivotal role in his life. Though keenly observant, Wil had never hunted. Ron invited him to pursue pheasants and ducks in the meadows and pothole ponds of Pennsylvania’s Delaware Valley. He took to it with enthusiasm bound only by his chive to paint first.

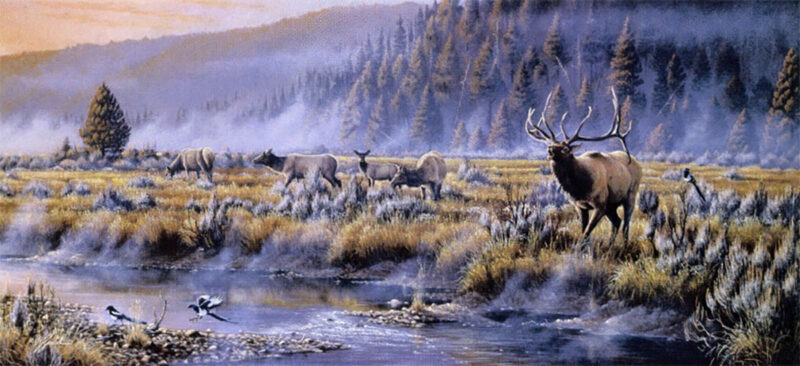

Though known primarily for his images of gamebirds, Goebel is an accomplished painter of big game animals. Autumn Classic – Elk

It wasn’t until his move to the Eastern Shore — a mecca for hunters, Wil calls it — that he began to hunt seriously. Famous waterfowling marshes are an hour’s drive west, the Atlantic with its surf-running stripers washes the mast an equal distance to the east, and in-between lie hardwood forests and swamps.

“I love turkey hunting,” he explains unabashedly. “It demands a lot of knowledge of the bird and its habitat. There’s the skill of calling. Anything can happen, which is what I love about it. A bird comes off the roost, gobbling hotter than ever; you think you’re going to get him and a deer walks by and scares him away. To be out at dawn and to hear the birds on the roost, to hear the woods all waking up; it’s magnificent. As frustrating as it can be at times, it’s my month out of the year.”

When Wil sits with his back to an old pin oak or crouched in a duck blind, every fiber of his being concentrates on willing a big tom or a flight of pintails into gunning range. But there’s a tiny bit of consciousness which records the scene around him, the way the morning sun climbs down a tree to warm the ground, the nod of a trillium, how the dew glows and fades with a passing cloud. You and I see the same things that Wil does. Yet it is his talent to articulate, in oils, those scenes that we feel when we hunt.

“I don’t want my work to look like a photograph,” he states adamantly. “I paint what I see — the color, the composition, the lighting.” His are not paintings of pheasants or grouse or elk. They are paintings of his experience, framed with the scientist’s scrutiny, mellowed by a bit of impressionism that lurks somewhere between his mind and his brush dabbing tan on the stubble’s stalks.

Wil tells me that the work of wildlife artists tends to become looser as the artist ages. Perhaps that’s the failure of eye and hand that plagues us all as we age. Perhaps, too, it’s the dream, the fact the ultimate truth of a thing is never found in the details but in its perception. He sees this in his own work, he tells me, a softening of backgrounds, less detail-defining contrast. It is as if he is painting a memory and in his mind and in the notebooks neatly aligned under the window of his studio are memories that I can’t wait to see.

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now

Featured on these pages are more than 280 paintings dating from the early 1970s to today. You’ll join the artist on adventure-filled journeys across North America, Central America, Africa and Asia and discover a vast portfolio of wildlife, including lions, tigers, bears, white-tailed deer and more. You’ll enjoy his gripping and refreshingly honest accounts of the experiences that inspired his artwork. In his stories, Sieve shares his deep commitment to land and wildlife conservation practices and recounts his adventures observing, photographing and hunting his wild subjects. Buy Now