Not everything in Africa that tries to kill you is even alive.

Well, okay. I’ve since learned that that first sentence is a bit of trumped-up, deltoid-pumping rhetoric. Maybe you’ll forgive me, though, because at the moment it happened, I genuinely believed I would die. Come to think about it, despite what I’ve read in the meantime, as I go back to what it actually felt like, well, to hell with academia. The stuff was trying to kill me.

We were after kudu. The terrain was textured, near the Zambezi River on Lew’s concession, brush and ridges and copses of trees all tan and brown, not jungle green and black, the predominant colors. This was not some deep, dark Doctor-Livingston-I-presume thing. There were maybe six or seven in our party. Rory was the PH. Since we weren’t at that moment actively tracking anything, we’d spread out laterally, everybody looking to cross spoor.

I had on a hunting vest with maybe 20 spare rounds in it. I had a belt with a canteen, binos and a Randall knife. And I was carrying the Browning .375 rifle. Not a trivial load, but certainly nowhere near the weight of a full rucksack. On my feet I had a good set of well-broken-in leather bush boots. They had thick soles, durable but suboptimal for feeling the ground. That said, I can’t tell you that, had I been barefoot, it would have made a difference.

I was headed downstream to the east, with one other guy to my right. I was moving downhill, looking for spoor while crossing what looked like a little muddy inlet. I was three solid steps, maybe four, onto a sandy gray surface before I had a warning light on the dash. Like low tire pressure or something. Whatever the hell was wrong with this ground, it had gone from bearing my weight without complaint to suddenly, aggressively seizing both of my boots.

As I went to lift my right foot, the warning light on the dash went up in a roiling mushroom cloud and blew the dash pad through the windshield. The whole rest of the dash hit the endocrinological klaxon, all at once.

My right foot would not move. Not at all. And as I tried, the hideous stuff oozed and squished up over my ankles, drawing me in farther.

Perhaps I descended from stock that somehow managed to just barely make it out of the La Brea Tar Pits. Perhaps, and more likely, the fear of being trapped is in us across hundreds of millions of years. However it got there, I can tell you with pealing, chest-reverberating, hell’s bells’ awfulness, that you never, ever want it to happen to you. A lunging Cape buff, so long as I am armed, doesn’t come close to triggering this kind of core response. Any variety of toothed felid intent on redistricting my abdominal vote is just fine with me in comparison. Even that drunk, power-lifting chick with the axe would be welcome compared to this. Becoming the mouse on the sticky trap is a core fear to end all core fears.

When under great stress, I seem to be able to yell to others, but for reasons that neither my shrink nor my bartender have managed to sort out just yet, I never remember what I yelled. Reliable, allegedly unpaid witnesses always concur later on what I said, but there’s no way I could tell you myself.

Apparently, what I yelled this time was,

“Stay there!”

The general, inaccurate, and overused term for the stuff into which I had sallied forth is quicksand. That word did manage to make it into my head at just about that time. So here’s where we get back to you forgiving me. In the 1960s, there was a whole bunch of movies that featured quicksand. I suspect that I saw every last one of them. But in those movies, nobody did density analysis and non-Newtonian fluid dynamics. They just had the hapless secondary-level character disappear until only his studly Stetson sat floating on the insidious Jell-O.

All of which immediately rocketed into my head.

Now up to the mid-calf.

Every time I tugged, twisted, or yanked, I went palpably and immediately deeper.

Two inches from the kneecap.

An aching, yearning, tearing fear went from welling in my chest to suffusing me, owning me. I needed out, and I needed out right now.

Knee covered.

OMG.

The irony wasn’t lost on me. To have survived so many safaris to this point, to have lived in the face of buff and crocs and hippos and lions and leopards and terrorists with AKs and RPDs and RPGs, only to be killed by a mud puddle with an attitude.

Mid-thigh.

Upon eventually 747ing myself back to Chicago, I went right over to my local library and reacquainted myself with the Dewey Decimal System. Remember that? Three-by-five cards in exquisitely crafted, long, narrow wooden—wooden!—file drawers, complete with annotations in pencil by highly repressed librarians just looking for a returning African adventurer.

Quicksand is what’s called a colloid hydrogel, in part sand (or silt) and in part water. When sand gets liquid-saturated and the water has nowhere to go, this stuff results. It turns out that it often looks, feels and seems quite solid, right up until you take a couple of good steps on it. That change in pressure initiates something called “liquefaction.”

People who know a lot more about it than I do call this “non-Newtonian behavior.” I call it damned disturbing. Anyway, the minor stress of your right boot-sole hitting the stuff initiates a severe drop in viscosity. Then, some separation thing occurs that makes the politics of the Balkans look like a Lutheran fall campout, the bottom line being you are well and truly stuck. Unless you can somehow reintroduce all the liquid you just displaced, you can confidently place a permanent pin in your Google Maps database reading “Me.”

Okay, now I know this stuff won’t kill me, except maybe by starvation or deprivation of the fairer gender. The reason for this belated if happy revelation is that no matter how nefarious a semiliquid is, it is still just a semiliquid. Which means that you can’t sink in it any better than you can sink in water and, given that it’s more dense, not even as well. Bottom line: most people sink up to their floating rib. But as soon as you’ve displaced as much mass of this stuff as you weigh, well, you can bob around indefinitely with grave threats to your dignity but no threat to your Stetson.

I didn’t know that then.

Up to the waist.

What I knew right then was that I was in the single most terrifying thing I had ever encountered in Rhodesia, in Africa, in the hemisphere, in the solar system.

Enter Simon.

He was maybe late 20s, over six feet, lean, African, tough. Really tough. You could take one look at him and know that he’d survived more tragedy, confrontation, heartache, abrasions, contusions, hypothermia, sunburn, snakebite, lacerations, deprivations and puncture wounds than almost anybody who lives in a place that has a zip code ever would.

The man took command. He started issuing orders, but everyone else was too far away to hear.

There were many trees around, including one big one just off to the side of the killer Cool Whip. And in wonderful fortuity, it had a big branch extending over the stuff, more than enough to hold weight.

Simon scaled the tree like he was two-thirds squirrel. Then, slowly, deliberately, knowing he couldn’t risk a fall, he worked his way out on the branch.

The geometry wasn’t just good—it was brilliant. From my personal perspective, it rivaled the work of Jonas Salk, Edward Teller and Thomas Edison all put together.

Lying flat on the branch, left cheek buried into the bark, Simon extended both hands. They just met mine.

I guarantee you that Simon hadn’t done any post-doc work at MIT. But I am here to tell you that the man absolutely, positively understood the practical applications of everything he could possibly have absorbed in any one of those avenues of higher learning. He understood, and he risked himself in the process.

Oh so gently, he and I both pulled. It took the weight off my legs.

I very gently eased them back and forth, which created some space, which got liquid back into the associated sand, which then dropped the viscosity.

Then, in a long, hard, awful, wonderful motion Simon pulled me loose.

I don’t think that either one of us had given any consideration as to how to proceed after getting me clear of it. He was holding my whole being and gear in midair with both hands, kind of a human gantry crane. Except instead of big steel rollers, he had his chest on rough bark.

Inching slowly, we worked together back down the branch. Lord knows what abrasion he suffered under his shirt, but it sure didn’t affect his dedication—his hands and forearms might as well have been constructed of steel cabling and hydraulics for all the effort he showed. Move, reset, hold. Move, reset, hold.

When at last I could reach out a boot-tip and offload some weight on real ground, I heard him sigh and knew that his silence had covered brutal exertion. One more inch forward and I got both boots down, and he relaxed the cabling of his grip.

For the first minute, I lay down, utterly spent and grateful beyond comprehension. Then, I thumped the terra cognita and shakily stood up. Simon had taken the same breather up in the tree and then nimbly eased down the trunk.

I did the most heartfelt, sincere thing that I could think to do under the circumstances. I unbuckled my belt, complete with my Randall knife and Swarovski binos, and handed the whole thing to Simon. In that place, at that time, for a local to possess either one of those objects was more or less the same as having a Lear Jet and nice place in Boca. For a great many locals, either the knife or the binos would have been worth what they earned in a year, even had they been able to find a place to buy them.

We looked at each other for a long moment. Verbal language aside, he knew, and I knew, and he knew that I knew. That was all there was.

I extended my hand to him and stated that I would never, ever forget what he had done and that for the rest of his life he had my complete support in any way I could possibly ever give him.

How’s that Bob Seger song lyric go? “Wish I didn’t know now what I didn’t know then.”

It was only ten days later.

Every operation we’d conducted up to then had, quite pointedly, included Simon. I made a point of publicly further acknowledging him. Authority. Money. Gifts. The whole nine yards. While I have a lot of character flaws, the one thing I am not is an ungrateful bastard.

On a safari operation, we get up early. I mean shock-your-suburban-sensibilities early. Like two hours before any celestial body can be bothered to contemplate turning over, growling, and sending off some light.

Part of it is pragmatism. It’s to make sure the vehicles are fueled, oil is topped off, chop box is loaded and stowed, ammo is checked, maps are marked. And part of it is simply the ethos of getting up too damn early. Coffee percolating—yes, ours still percolated—before sunlight arrived is an ethos. So is a cast-iron frying pan over a campfire with almost anything in it. It is the slow susurrations of a camp getting moving, clanks and clicks and low voices speaking a language you don’t. If it gets as far as the sound of an internal combustion engine turning over and you’re still in your sleeping bag, you’ve been lying there too damn long.

All of that allows us to be moving at first light. Many animals—many, many animals—make a living in the hour that crosses dawn and the hour that crosses dusk. They spend the other 22 somehow desiccating themselves into one of those blue capsules you can throw in warm water to get a stonking foam narwhal or something. But in the two daily hours of activity, you may see them. You may track them. You may, if they are what you are after, shoot them. Otherwise? They can disappear in a room with tenoned hardwood floors. Then there is mustering the local help. Good local help, like good employees in St. Paul, Minnesota, are simply there. But as with St. Paul, there are employees who aren’t. One missed his girlfriend/mistress/wife/cousin/ sister and skipped out to go put things right. One had a fight with a co-worker over some eland meat from a safari seven months ago.

One managed to lay hands on the local hooch, which is called “shake shake.” You start it fermenting on a Thursday and by Sunday, Carrie Nation and Elliot Ness together would stand no chance of settling things down. In fact, I’d pay big money to watch that effort. Did I say that one guy laid hands on this stuff? In point of fact, if any of it is around, they will all lay hands on this stuff. The question is not one of access, and the question is not one of prudence, but rather, it’s one of relative resilience: some can get up in the morning. Lots can’t.

When I’d called the roster that morning, there were a few AWOLs, but Simon had, with stalwart reliability, been there. Off we went.

Midday in Rhodesia all but required a siesta to do Don Quixote proud. The heat transcended oppressive, the overhead sun abdicating its role as giver of light and heat and energy and life, instead going on an overload bender of heatstroke and exhaustion. The only remedy was evasion—staying in the shade, dropping exertion, keeping down core temperatures. Which is exactly what we did. Today, that period ran something like from 1100 to 1400.

Then we began to prepare again. Since there isn’t any midday shake-shake to deal with (or at least not as a rule), attendance in the afternoon is usually 100 percent.

Not today. Simon was gone.

I started the query. Anybody know about Simon? At this point in the process, I’d only been on safari a few times, but I still fancied myself an increasingly seasoned old hand. Of course, all that means is that Africa still had graduate studies for me. I asked where Simon was and got an answer that sent electric fear down my limbs.

“Simon is dying.”

I have been a licensed pharmacist for years; more importantly, with or without that credential, I know a whole lot about keeping people alive. While I generally strive to be warm, friendly and approachable with staff and everybody (with varying degrees of success), I do have to confess that my concern for Simon left me with no margin of humor in hearing that sentence.

“What do you mean, he’s dying?! I can probably fix it! Let’s go!”

I’d expected that explosive response to generate hope. To generate enthusiasm. To generate cooperation, with the prospect that their friend might live. Nobody so much as shrugged.

I’m afraid I may have tarnished my reputation for being accepting, caring, and respectful to the staff, because I said something to the effect of “Damn it, look me in the eye—why the f*&A won’t any of you respond? I am here to save your friend.” This was not delivered in a Mister Rogers voice. Think something more along the lines of an over-caffeinated Jack Nicholson after missing out on an Oscar and whacking his thumb with a ball-peen hammer.

No eye contact from any of them. Movement away, body language showing total disengagement.

I grabbed the closest staff member, none too lovingly, and spun him around.

“Where is Simon, and what’s going on?”

He demurred and writhed out of my grasp, gesturing widely away. “Simon is dying.”

He was the closest staff guy to me, and I was mad now. I grabbed him again and spun him back around, not wanting to, but needing to.

“WHERE is he?!” Not a question. A demand.

The man wasn’t afraid, but he was in severe avoidance. No response from the grab, no verbal rise, no meaningful reaction other than to say, “His village.”

Well, I knew where Simon’s village was. I’d been there.

I grabbed my pharmaceutical rucksack, jumped in the Toyota, wound it up, and dumped the clutch, dumbfounded that his friends had zero interest in attempting to preserve him.

The village was on the concession less than 1,000 yards away. I roared in with the full wrath and majesty of an American guy with good intent who associates himself just enough with the English to think that he can blast around a former colony issuing mighty commands, and that maybe, just possibly, someone will listen. I stopped the first passing person I saw.

“Where is Simon ?!”

The poor soul directed us to Simon’s hut by pointing but avoided eye contact. Whatever the hell was going on with Simon, it carried more social ostracization than my publisher would let me use in my original analogy (the original analogy was truly outrageous). Whatever it was, it was bad.

The hut was a thatched roof deal with steel siding. By that point, I had full rescue adrenaline going.

Ever have it? It’s a rare thing in the first world. Most folks dial 911 and that’s that.

It’s a funny thing: I’ve helped people I don’t know, and none of the serious rescue response was triggered. But if you are called on to help someone who has woven himself or herself into your neural net as Someone Who Matters, then Katy Bar the Door with a Cement Mixer because Here It Freakin’ Comes. It’s a full-on adrenal cascade coupled with all the stuff that lets grandmas lift combines off grandsons. It is horrible fear coupled with a sudden and total mental shield against the prospect of personal damage coupled with a truly stunning drive that I am going to accomplish this mission, or I WILL die in the attempt, and I am JUST FINE with that.

Someone under this kind of influence has a tendency to dispense with the finer points of normal social niceties. Indeed, someone under this kind of influence will emphatically and endearingly commit every felony that comes to mind if it will help the mission.

The door was unlocked, which proved really beneficial for both the door and the doorframe.

I didn’t knock.

Two women were present, snapping up with startled looks. It was only one room, but it had been sort of divided by hanging screens.

“Simon!”

Two fingers, pointing.

I rounded the screen like a bull buff on a last mission. He lay on a homemade mattress, woven or rolled matting with another mat on top. His eyes flickered up at me, and my immediate instant impression was that he looked fine.

“What’sgoing on?”

“Thanks for coming, boss. I feel fine for now, but I am dying.”

I tried to digest that, and maybe percolate off a little of the I-am-rescuing-you-dammit-as-I-walk-through-walls effect. I managed, “Does anything hurt?”

“No.”

“How’s your energy?”

“Fine.”

“Well if nothing hurts and you feel fine, then how in Satan’s cesspool do you think you are dying?!”

He shrugged and rolled his face away.

I was having none of it.

I dropped to one knee, grabbed him none too gently by the right shoulder, and slammed him back, to look him in the eye.

“See this rucksack? It contains the best medicine that all of human civilization has ever produced. I will use it to save you, just as you saved me. I will SAVE you. But you have to tell me what is wrong!”

He sighed and started to turn away, and I responded viscerally. I was on a lifesaving mission for a man to whom I owed my life, and he was acting like a petulant three-year-old. I went to grab him, and he saw it coming and decided to talk.

“It’s okay, boss. I deserve it.”

“You deserve WHAT?”

The man just shook his head and turned back to look at the wall.

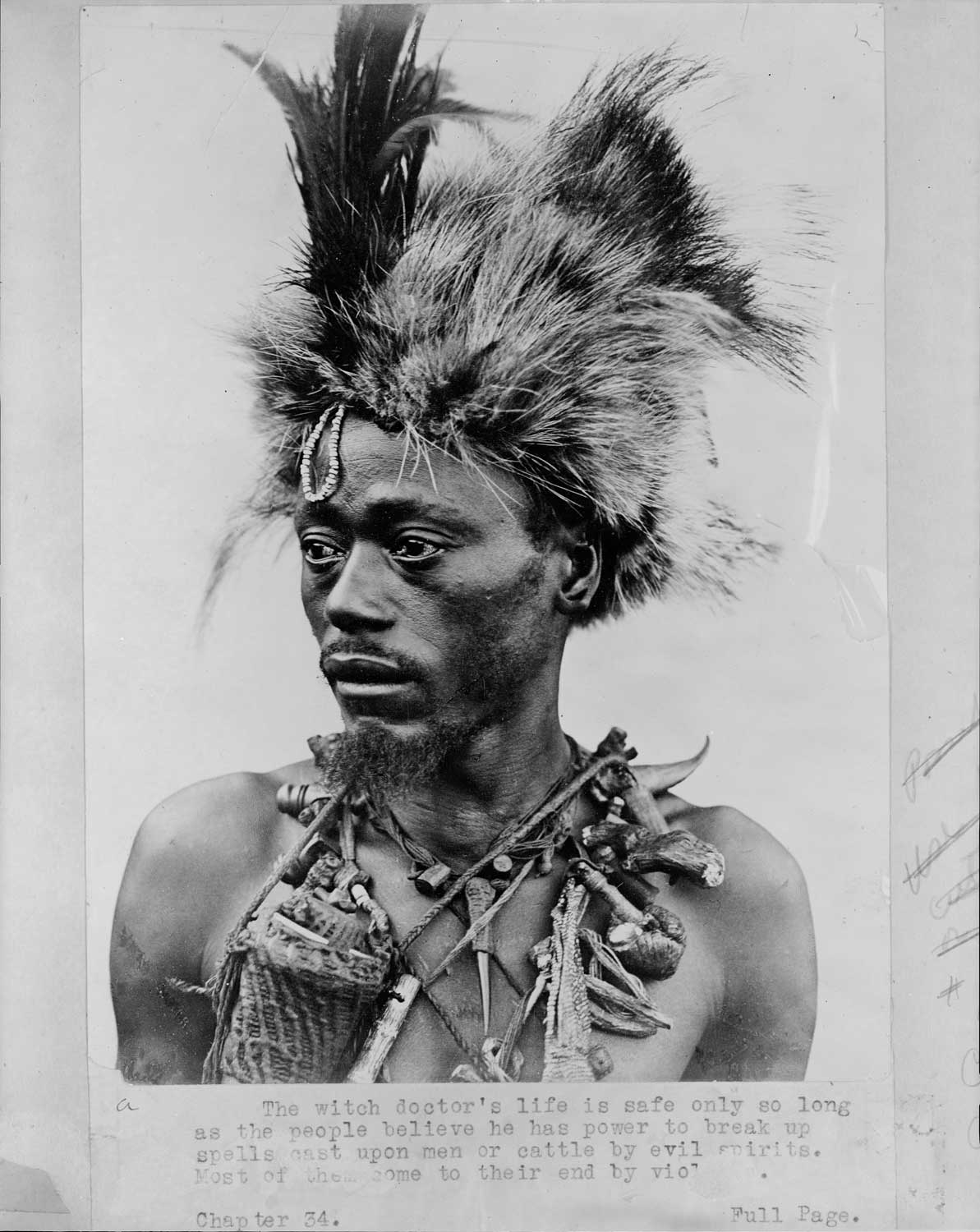

“Witch doctor put the curse on me.”

“What!?”

I had to let that sink in for another couple of seconds. Then I followed with, “I’ll go see him!”

He shook his head.

“F&*$ it! I’ll go shoot the sonofabitch!”

A flickering eye contact of fear, then vehement head shaking.

“No. No. No. It is better this way.”

I stayed. I cajoled. I threatened. I shook.

The man was beyond caring.

I sat there way, way too long. He wouldn’t talk, wouldn’t respond.

I just could not comprehend it.

Finally, there in that squalid little hut, someplace in northwest Rhodesia, by the side of a man who had saved me and under the sideways glances of the women, I stood up and walked out.

Back at camp, I finally pried out of one of his friends what happened. Simon, it turns out, was every bit the paramour that you might have imagined. But his capacities had outstripped his judgment, and the daughter of the local witch doctor had fallen within his charms. When dad found out, dad did what I have to imagine that witch doctor daddies the world over would do. In my universe, it would have been a Remington 870 or a Winchester Model 12. Apparently, if you are a witch doctor, you whip out a hexoramic-curseblaster. He let old Simon have it.

Simon believed it, and everyone else believed it, too.

Which, it turns out, is enough.

Three days later, with no sign of physical violence, with no sign of toxic event, Simon died. It was literally as if, upon being hexed, he decided that was as good as being dead, and some part of his brain set about making it happen. In his brain, that was better than whatever imagined horrors might have accompanied an effort to save him. The witch doctor had conclusively whacked him, and that was that.

The brilliant, best-selling novelist Wilbur Smith has written extensively on the Dark Continent. He phrased it this way: “Wonderful, endlessly fascinating, ever-changing, never-changing Africa.”

Perfect.

Editor’s Note: This story is among 20 chapters in Facing the Charge – African Dangerous Game. The 180-page book features adrenaline-fueled tales of big-game hunting and details how death was a constant companion on safari in the form of terrorists, quicksand, malaria, and witchcraft, among other threats.