The twin, rock-ribbed walls that vaulted straight up nearly a thousand feet above the shimmering waterway that was Putah Creek were aptly named Devil’s Gate, and gateway it was, leading to a broad, flat valley that lay miles beyond the mountain’s narrow stone notch. That land was dotted with white-faced cattle grazing on summer-tanned wild oats, scattered orchards of fruit trees, plus a few clapboard ranch houses and barns that had seen little change for most of a century. At the far end of the valley stood a thin line of buildings that was the old cow town of Monticello. In the simmering August heat of northern California, it seemed like time had passed all this by. Change was not part of that quiet land, nor wanted by those who still lived there.

As a teenager sporting my very first car, a 1931 Chevy coupe with a rumble seat in the back and steel, spoke-wheel tires, I made the long drive along Putah Creek all the way to Monticello one blistering hot summer’s day. When I pulled into the only gas station left, the owner leaned on the countertop and began regaling me about Monticello’s wild and wooly past.

“Yes sir, it happened right out front here,” he said, pointing through the screen door to the dirt street.

“Both rancher’s shot it out, man to man, just like them old-timer’s did back then.” He squint-eyed me for response.

“Was anyone hurt?” I wondered.

“Hurt? Hell yes, one of ’em was killed! This little town’s got a whole lot of history behind it, and now they want to build a dam down at Devil’s Gate and back up water all over the top of us. Damn them federal people in Washington. Why don’t they leave us alone!”

I drove away that day thinking about what he’d said and my own emotional connection to Putah Creek, long before I’d secured my first driver’s license. Back in the middle 1940s, I spent many long, summer weekends as a youngster camping out and chasing the little smallmouth bass that called the scenic waterway home.

The misery and bloodshed of the Great War had finally ended when I turned 10 years old. America took in a deep, collective breath of victory and time of remembrance. At that same time, I became fascinated by the idea of catching those elusive smallmouth using a fly rod and a fluff of feathers instead of my usual gear floating a live grasshopper or worm under a bobber, praying for a bite. I was moved to this strange new sport by a story and photos I’d seen in one of the many outdoor magazines I devoured.

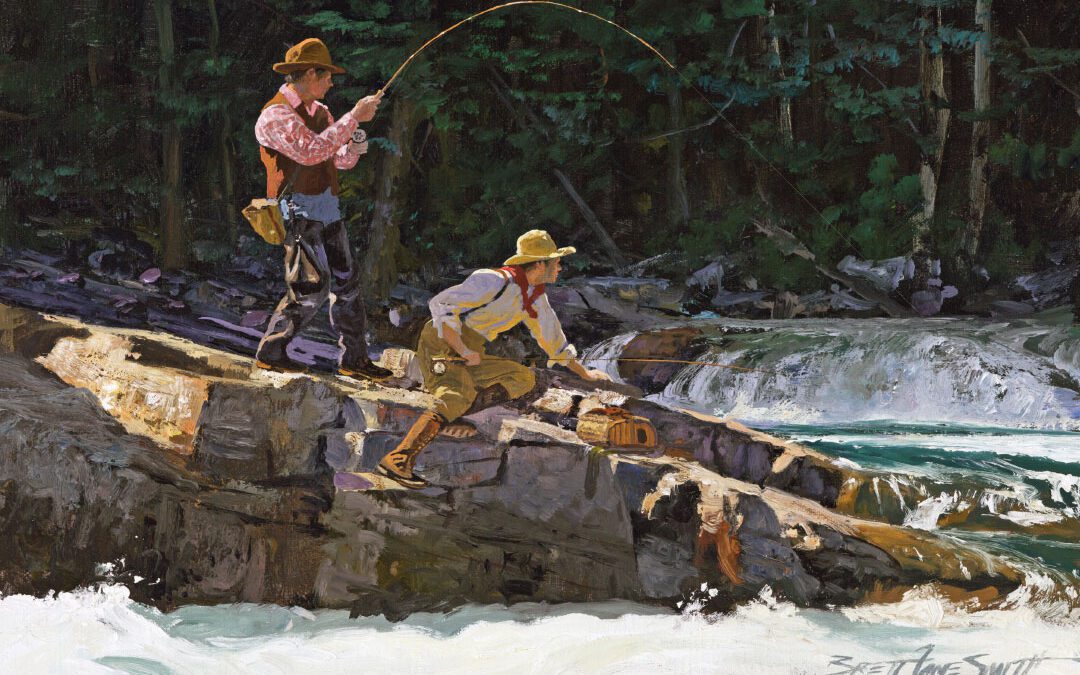

Choosing Flies by Brett James Smith.

The money I earned from my big paper route wasn’t enough to buy a real three-piece bamboo fly rod. Instead, I had to settle for something that looked like a fly rod, but wasn’t nearly up to that. I got my hands on a steel telescoping rod that weighed about five pounds minus the reel and line. After each outing, I had to apply a liberal dose of 3-IN-ONE oil so each section would slide easily into the next. After just half-an-hour of casting the rig, my arm would be completely worn out. But the odd contraption did have upside. When compressed into a sort of steel club, I could hack my way through streamside willows and brush to reach an especially productive piece of water.

Readers will have to understand that what westerner’s jokingly call “creeks” are really not creeks at all, but full-grown rivers and streams just about everyplace else. In winter, Putah Creek drains tens of thousands of square miles of rugged, Coast Range Mountains, turning the waterway into a wide, raging torrent of muddy, brown waves that ate up banks in huge bites and took down trees with it. You could actually hear its vicious roar even before entering the canyon.

In summer, it magically calmed down to a wonderful stream that danced over boulder-strewn rapids into sepia pools and long, glassy runs where smallmouth bass lived and prospered.

My frequent trips to Putah Creek made it clear that the smallies had only two times of day when they fed voraciously and were the most vulnerable. This was early at dawn until the sun lit the deep canyon, and again when it went out behind Devil’s Gate and long shadows silently invaded the waterway. At those times I could sneak up and watch their slender, torpedo-shaped bodies finning just under the surface before shooting to the top to take some hapless insect.

This timetable set up a problem for my mother who had to make the long drive from town in the dark before dawn, then pick me up after dark that same day. I solved that problem by suggesting she let me camp out along the creek on summer weekends. Somewhat reluctantly at first, she finally agreed. After all, what harm could come to a 10-year-old boy thunderstruck by the idea of becoming a fly rod aficionado, even before turning 11? This was the outdoor world—clean, secure and healthy. It was also a very different one back in 1945, than today.

Before my next trip to Putah Creek, I rode my bike down to our towns’ one and only hardware store. I’d seen they had a small selection of dry flies tucked away nearly out of sight among various lengths of pipe, sheet metal and heavy tools. I knew nothing about fly selection and told the owner and only employee as much when he reached down and brought up a small plastic box with several varieties of flies in it.

Without a clue to go on, I chose the brightest colored ones I could afford: a Royal Coachman, Red Ant, one Black Ant and one with grey hackles but a golden floss body tipped in a brown tail. I was now ready to take on Putah Creek and its secretive smallmouth bass, fooling them into strikes with my fancy new flies.

That first night in my chosen camping spot on a sandy berm close to water, I built a small fire, ate a sandwich for dinner and then wiggled into my Army surplus sleeping bag. I sat back, watching the canyon walls turn into dark shadows before the sky above went coal black with icy stars so close it seemed I could reach out and touch them. I was alone and a little afraid, but thoughts of the next morning and my new flies warded off the boogeyman.

At the first hint of dawn, I shivered out of the bag into cold tennis shoes, shunned a warming fire as taking too much time and grabbed my fly rod. After creeping down to the edge of the nearest pool, I peeked over tall grass lining the water and there they were, half-a-dozen smallies finning quietly just below the surface. Still on my knees, I began working out the yellow waxed line farther and farther until I dropped the Red Ant just a few feet upstream from the feeding fish. That was the exact moment my unforeseen troubles began.

Line, leader and fly hit the water all at the same instant with a resounding splash, sending the little bass spurting deep out of sight. I was stunned at what had happened. Reeling in, I came to my feet. The moment I’d planned and waited for all week had just ended in disaster.

Perplexed what to do next, I decided to change flies, choosing the fancy Coachman, and began waiting for the bass to return so I could try again. They did not. Eventually I gave up, moving downstream to the next piece of water where I’d seen fish before, already beginning to think this fly fishing business might not be as quick and easy as I’d seen in all those magazines. My concerns proved correct. The only thing I ‘caught,’ was a sore shoulder.

The following Sunday morning, the sun was climbing above Devil’s Gate as I continued my assault on Putah Creek’s smallmouths. It ended without raising a single fish—again.

Back at camp I sat, crestfallen. All my careful plans had come to nothing, but I still had one last chance when the evening feed would commence again. Although that proved to be another heartbreaker, at least I was not unobservant even in my misery.

Smallmouth Bass by Philip Russell Goodwin.

When long shadows silently put out the sun behind high rock walls, a sudden flight of light-colored moths appeared over the water as if by magic. One moment the air was clear and still. The next they seemed everywhere, flitting just above the surface like so many dancing fairies. The smallmouth rose and went wild devouring the moths while splashing the surface in endless rings of water.

I desperately cast all my fly patterns without a single hit. However a new idea began to form in my head. If I did not have a fly that matched what these fish were taken with such gusto, maybe I could make one of my own?

Back in town I went to the hardware store, carefully going over the only fly selection I could get my hands on. Nothing in the plastic box matched what I wanted. The clerk and owner came up asking if I needed help. I explained his lack of selection and my dilemma up on Putah Creek. He thought for a moment, grabbing his chin.

“Wait a minute, I think I might just have something.”

Reaching down, he slid the display door open, bringing up a long, narrow dust-covered box.

“I almost forgot I still had this. I never sold it and put it away.”

He opened the box revealing a long-necked fly-tying vice with pointed jaws, a red gnarled handle to clamp it tight around a hook, and a slender body with a screw clamp at the bottom to secure it to a table. In the bottom was the folded instruction sheet. I bought the odd-looking contraption on the spot, plus a small packet of hooks, then peddled for home as fast as I could. New life and hope had been breathed into my budding fly-tying career.

My mothers’ thick, mail order catalogue, from which she ordered all manner of items from clothes, shoes and once even a tire for our old 1932 Plymouth coupe, had a small section of fly-tying equipment. I devoured every picture and explanation, ordering a mixed package of hackles, wooly colored body wrapping material, gold and silver tinsel spools and a bitty bottle guaranteed to keep your dry flies afloat with just one delicate application.

I watched each day’s mail like a hawk until my package arrived and I tore it open. Now I’d make my own flies, by God, come hell or high water. I was going back to Putah Creek, and this time armed with new knowledge and new offerings of my own design.

That week after school, between fly-tying sessions in my bedroom, I diligently began practice-casting on my front lawn, swishing the steel rod back and forth while inching more line with each effort until I could drop the fly before the line and leader hit the water. It took real practice, timing and finesse, but I finally got the rhythm right.

Next Saturday morning, when the first rays of sun fired the tops of Devil’s Gate, I was back at the big pool where the rapids splashed in. So were the smallies. On my knees so as not to spook the cautious fish, I began playing out line with my newest creation, a white moth carefully tied on a No. 14 hook. It gently caressed the water, settling in just upstream from the waiting fish. As it drifted over the top, I twitched the rod tip to make the fly dance seductively.

Wham! A smallmouth instantly rose and inhaled the fly. I struck back, the surprised little bass cutting left and right, trying to spit cold steel. Not this time . . . not on your life. The sturdy steel rod quickly wore him out before I scooped him into my net then laid his shimmering bronze body on a fresh bed of grass in the bottom of my wicker creel. I had my very first smallmouth, and now I had the secret how to catch more.

Who cared if I could not consistently shoot basketball hoops from the free throw line, or toss a perfect spiral with a football. I’d learned secrets that morning far more important, secrets that would last a lifetime. I was a fly fisherman, by golly, and I had a fish to prove it!

Summer vacation meant I could spend more time on Putah Creek than just weekends, showing me more of its amazing secrets. One sunny mid-morning I hiked far downstream, stalking grassy banks under twisted, old cottonwood trees. The sun was high, full on the water, a time when fly fishing always proved to be at a low point. It was more a mission of exploration as much as fishing.

I stopped on a grassy bend to look across the widest part of the waterway when a big, fuzzy bumblebee suddenly dive-bombed me. Maybe it was my yellow-billed cap that caught his attention. Twist and swat as I did, he kept coming back and getting closer. I finally pulled off my hat, grabbed it by the bill, and the next time he dove in, I swung hard and fast, knocking the bee into the water nearly at my feet. Suddenly a kaleidoscope-colored bluegill the size of a coffee saucer shot to the surface, gulping down the hapless bee, stinger and all. I was dumbfounded witnessing the savagery of its attack, and I would not forget it. The idea for a new fly was in the making.

Back home at my fly vice, I went to work tying chenille bands of yellow and black on a No. 12 hook. For a head, I wound on one brown hackle, the tail a tuft of red, completing two more of the same genus.

I used that fly on big bluegills endlessly and with great success that summer. The odd thing about that fly is not once did it ever tempt a smallmouth into taking it. I’m still wondering why?

That my flies only lasted two or three days of casting before beginning to unravel bothered me only little. I would learn to tie better knots and double lacquer the heads.

My boasting about success up on Putah Creek did not go unnoticed. My boyhood pal, Jim Cupp, also had acquired the sudden desire to become an expert fly fisherman. Jim joined me in inventing an endless array of wild-looking flies never before seen by human eyes.

I had been thinking about a name for my deadly little white moth fly when I learned from a book on fly patterns that, years earlier, someone had stolen my idea and named it a White Miller. Well, not to worry. Jim and I had an endless array of originals we could come up with, and a pair of wild imaginations to match.

Side-by-side up on Putah Creek, we flogged sundown waters catching smallmouths until it became so dark we could no longer see risers, only hear them out there in the dark still slashing the surface. That’s when Jim came up with an idea for a veritable 747 of all flies we nicknamed the Feather Duster. Its design was so huge that fish could still pick it up in the last shadows of evening and even after full dark.

The monster fly was tied on a big, long shank hook with a cluster of grey hackles sticking out for a tail. The body was another fist-full of grey hackles wound around the hook to make it thick and wooly in addition to more grey hackles in a 360-degree pattern sticking out around the head. It took Herculean effort just to keep the fly in the air. Because of its weight and fluffy design, it was not the most aerially dynamic to cast. It tended to slap the ground on back casts, or rip through the tops of brush and tall grasses before we could bring it forward. Although it sank quickly, it proved to be a staggering success—pure stroke of boyhood genius. We caught smallmouths one after another, with Jim catching a monster 13-incher one evening.

Far downstream from our usual fishing grounds below Devil’s Gate, the waterway ran for a mile through a stair-step series of willow-lined rapids emptying into sloshing pools before suddenly turning due south. There, the valley opened up and Putah Creek flattened out into broad, glassy runs moved by a slow, unseen current. These runs were so wide I could not send a fly across them to probe the far side. Yet my growing savvy of the creek’s waters told me there had to be smallies hidden within this stretch of hard-to-reach water. The only possible way to find out was to float it right down the middle. I certainly had no boat or ability to get one, but I did have an idea. I decided to match my sleeping bag with a relatively inexpensive, two-man war surplus life raft. The little round float came with a black-barreled pump chamber and handle, plus one aluminum oar. It took a full half-hour of breathless pumping to fill it full size, but it floated as light as a cork.

Once at the water’s edge and ready to cast off, I loaded in the rod, reel, creel and net, plus two bottles of Delaware Punch to help me survive the July heat. Then I pushed off.

The gentle current set a perfect pace for me to sit on the front edge of the raft, my feet dangling in the water while I played out line ahead of me. The anticipation and expectations had me tight as a fiddle string, but without streamside brush or timber to hamper me, I could lay out long casts and worked up a sweat doing so.

My newest creation for this special assault was a little fly tied with a grey hackle up front and a brown, peacock body finished in a black tail, all wound on a No. 12 hook. I toyed with the thought of calling it a Wood Rat.

Even with a full sun on the water, I knew I was casting to unseen fish that had never seen a fly or any other bait before for that matter. I felt that gave me a big edge against the poor timing. I saw not one fish rise nor so much as a ripple on the mirror-like surface.

Dropping the fly far ahead, it floated for several seconds as I twitched the rod tip once, twice, causing the water under it to swirl and come alive. When the first fish hit, I struck back instantly. It was the beginning of a Red Letter day and one of hard-won success I’d never forget.

On that summer day and on many other floats on that quiet stretch of beautiful water, I never saw another fishermen. I had it all to myself, and the smallmouth secrets of discovery I made there.

As everyone eventually learns in life, the passage of time has a way of changing events and the people who experience them. For me, high school, my first car and young coeds sitting next to me in English class, meant my long summer weekends fishing on Putah Creek pretty much came to an end. But the dancing waterway of my youth was not done calling me back just one more time, and in a way I could have never conceived possible in my wildest dreams.

After finishing high school, I kicked around for several years going through a variety of unusual, uninspiring jobs. I drove a cattle truck loaded with mooing, jostling whiteface steers; loaded iced box cars with crates of fresh fruit to ship back East; became a gandy dancer swinging a hickory handled spike maul, laying steel rails for smokestack belching engines to come thundering over. For a time, I even buckled on a pair of leg spikes and a thick leather belt, climbing tall telephone poles to string wire along those same shining steel rails.

Turning 20, I happened to read a small ad in the local paper calling for young men to apply for a job on government survey parties preparing to do the ground work for a new dam to be built at Devil’s Gate on Putah Creek. Once completed, the huge lake would flood the broad valley behind it for many miles.

Here was my boyhood stamping grounds once again, but under far different circumstances. I applied for the job and was quickly hired, spending physically demanding days hiking over hills and mountains packing transits and steel chains to measure and record new boundaries on the federal lands that would be called Lake Berryessa and Monticello Dam. Berryessa was the family name given the old Spanish land grant whose ground the new lake would eventually cover.

As I was beginning my new job, the town of Monticello was being taken down board by board, house by house. Barbwire fences were cut up into three-foot sections and left to rust or rot. The old graveyard was even dug up, the remains of its earthly pioneers re-interred on higher ground above the expected waterline.

“They want to back up water all over the top of us!” The storeowner’s words still ring in my ears after all these years.

I needed the job, and it paid well, with a future building other water projects if you were willing to travel. But slowly it began to dawn on me that I had turned my own hand to changing the lives of those people who lived so long in that quiet summer valley. Every inch of it would be sunk forever under rolling waves and largely forgotten. But not by me.

The Monticello Dam, 304 feet high and 1,000 yards long, curved across the canyon at Devil’s Gate, each cement end locked deep in solid rock walls formed eons ago. The warm water preferred by smallmouth bass was killed off by the icy flows released from the bottom of the dam. Hatchery-raised rainbow trout were trucked into the canyon and planted into Putah Creek so people from large cities could drive there and experience trout fishing that did not require driving hundreds of miles into the High Sierra.

Once the lake was filled, boat marinas, camp grounds, boat launches, motor homes, RVs and trailer parks dotted the hills and valleys around the new lake. Tens of thousands of people now flock there every spring and summer, and new homes built for year-round residents are also popular. The project has been deemed a great success of man turning nature to his hand—and so it is.

Framed by the towering bluffs at Devil’s Gate, Monticello Dam impounded the waters of Putah Creek, forming what is now known as Lake Berryessa.

I don’t go back to Putah Creek anymore. Somehow, it’s become a foreign place to me, hard to recognize or really enjoy. And I must admit I still harbor some small tinge of guilt that I had a hand in all this undoing. Now when I think back about Putah Creek, I much prefer to remember the picture in my mind’s eye of a 10-year-old kid with an unwieldy, steel telescope fly rod, sneaking up on smallmouth bass in a quiet pool fed by gurgling rapids.

That youngster is hoping against hope that his newest feathered creation will cause a fish to rise and strike. If it does, he’ll be back next weekend with another wild creation of cold steel hidden under fluff and feathers. If not, he’ll keep on trying with other nameless patterns until a bronze-bodied smallmouth swirls the surface and flashes its side, turning against the sting of a razor-sharp hook and tight line.

Those are my fondest memories of Putah Creek, although I may be the only one left who remembers it as it once was. I wouldn’t change one moment of them even if I could. Those were wonderful moments to last a lifetime. How lucky I was to have lived them.