So when the opportunity came for him to go north from Virginia to hunt grouse in classic autumn Michigan, he stashed his old fiberglass fly rod in the truck as well, on the off chance that he might come across a suitable trout stream.

Carl preferred to travel light and travel at night. So he and Aldo, his young Llewellin setter, hit the road one cool Tuesday evening after supper with their 16-gauge Parker, two boxes of number 8s, a small duffle with fresh clothes, and Aldo’s little silver sleigh bell that clipped into his bright orange collar. By the following afternoon, they were hunting in full flaming autumn.

For eight days they hunted the great Huron Forest, from McKinley to Mio and all the way east to Glennie. But on their last afternoon, Carl decided to detour west to see Lake Michigan, stopping to get directions, some Vienna sausages and a bottle of pop at a little gas station on the outskirts of Newago, overlooking the Muskegon River.

“How ya doin’?” Carl asked in his best Virginian to the crusty old cashier.

“Tolerable,” came the reply.

“How much farther over to Lake Michigan?” Carl inquired.

“’bout an hour . . . hour ’n-a-half. Depending on how much of a hurry you’re in.”

“Thanks,” Carl answered as he pocketed his change and turned toward the door. But then, almost as an afterthought, he asked, “How’s the grouse hunting ’round here?”

“Grouse?” said the cashier, with a blank look on his face. “Oh, you mean ‘pats’.”

“Pats?” Carl echoed, somewhat confused.

“Yeah . . . pa’tidges. We call ’em pa’tidges’ round here . . . you know—‘pat’.”

“Oh. All right,” Carl responded. “How’s the partridge . . . excuse me . . . the pats hunting around here?”

“Pretty poor,” came the answer. “You need to be fu’ther east.”

“Okay, thanks.” And again, Carl turned to leave. But as he reached the door, the cashier volunteered, “There are a few salmon in the river. If you’re interested.”

Carl halted.

“Salmon?” he asked, as he turned.

“Yeah. Chinooks.”

“Wha’ do you catch ’em on?” Carl inquired, his ears pricked forward.

“Spoons, plugs, jigs and the like . . . unless, of course, you’re fly fishin’.”

Carl took a deep, deliberate breath and tried to stifle the subtle, sneaky grin welling up beneath his week-old stubble.

“What kind of flies?”

“These.”

And the guy pulled a small beat-up metal fly box from his faded denim jacket. There followed ten minutes of some of the most intense negotiations of which Carl had ever taken part, and in the end he walked out with two chartreuse streamers, a pack of 3X tapered leaders and directions out to the Croton Dam.

By the time Carl and Aldo found the river, only an hour of daylight remained. They crossed the two-lane bridge 500 yards below the dam and found a small parking area with a narrow trail leading down to the northern shoreline.

Carl slipped into his chest waders, dug his fly rod from beneath his jumbled hunting gear and unwrapped it from its grey flannel blanket. It was a forest-green Horrocks-Ibbotson nine-footer with his wide-frame Leonard fly reel already screwed into the reel seat. He looped the tan fly line through the guides, nail-knotted one of his new 3X leaders to the business end, tied on one of the chartreuse streamers he’d just bought and turned to the river, leaving Aldo curled up in the passenger seat atop Carl’s red plaid hunting coat.

Carl Lear knew he was in trouble as soon as he reached the bottom of the trail, for with the wind whipping up from the south, he would be casting straight into its teeth.

But peering across the river, he could see that the wind was virtually nonexistent, the far side effectively sheltered by the high bluff looming above it. So he retraced his steps up the path, re-crossed the bridge on foot, and gingerly picked his way down the steep hillside.

By the time he reached the shoreline, dusk was fading into darkness. But the lights from the dam bleeding through the upstream mist, and those from the bridge 200 yards below, served to define the river’s surface well enough that he had little difficulty reading the intersecting currents.

His fly line looped tight and smooth out across the water and lightly landed the big streamer 50 feet in front of him. He gave it a few seconds to settle before starting a series of short, syncopated strips as fly and line began fanning downstream.

At the bottom of the swing, Carl made three long, sharp strips, then lifted the streamer from the water and re-deposited it four feet farther out into the current. Again he worked the fly all the way to the end of the drift. But just as he began to lift it from the water he noticed that his reel felt a little loose. And as he reached down to tighten the reel seat at the base of his fly rod, his line came suddenly and jarringly tight.

The hook-set was completely instinctive, and line began flying from Carl’s reel. His first reaction was to reach for the rapidly spinning handle, but he knew this would be entirely the wrong move. So he let the fish run, feathering the whirring spool with his fingertips until the salmon halted in the darkness somewhere far downriver.

Carl had never experienced such power at the end of his line. But he had learned long ago how to play a fish and, more importantly, how to think like a fish, and he was cautiously confident that together he and God would figure out how to land this salmon. So instead of increasing pressure, he raised his rod tip high, maintaining only enough tension to keep his line tight as he carefully started picking his way down the rocky underside of the current, thankful for the shimmering lights from the bridge below.

As he worked downriver, he methodically lowered his fly rod an inch or two at a time, allowing more and more line to be carried down-current in an ever-increasing arc that eventually swung below the great fish, effectively applying directional tension from below. In response, the salmon began moving upstream against the pressure— which played right into Carl’s strategy. But the fish turned and tore away just as Carl was reaching for his reel, and the fast-spinning handle ripped into his cold bare knuckles.

The pain was fierce, and for a moment he thought his fingers were broken. Still, he instinctively tightened his grip on his fly rod and held on, anticipating the sudden jerk he knew would be forthcoming if all his backing ran out. But to his good fortune, the fish stopped just short of the bridge.

Carl knew the big salmon must surely be tiring by now.

He certainly was.

The pain in his fingers was subsiding, and his hand still seemed to work. So with only a few yards of line remaining, he continued inching downstream, gradually increasing the pressure until he finally came even with the fish.

In response, the salmon shifted upriver. But with its strength waning, the big fish began backing tail-first down the current, slowly closing the distance until Carl could see him.

For the first time he drew his tethered net from his wading belt, concerned that it was going to prove much too small. His only hope was to get the fish’s head and shoulders as deep into the net as possible, then try to grasp the base of its tail with his hand. What he would do with his fly rod, he hadn’t a clue— he’d figure that out when the time came.

The salmon was oriented upstream, tailing back and forth and still drifting backward. Carl let it pass him close to his left, for he knew it would be dangerous to try to net the fish from behind; he needed to net him head first. So as the fish settled into position a few feet below, Carl turned to face him.

Carl had never seen such a fish, and as he gently lowered his net into the river, he raised his fly rod and drew the salmon forward. For a moment he nearly had him, but the fish swirled away and reset, its broad fins stubbornly anchored in the current.

Again Carl tried the same tactic, and again the fish spun away. But then he had an idea.

This time instead of trying to move the fish, Carl moved himself, easing downstream until the salmon was again next to him. Then, once more slipping the net into the river in front of the fish, he angled his rod downstream and tugged the fish backward.

In response to the sudden pressure, the big salmon shot straight upstream and buried itself nose-first into Carl’s net.

To the end of his days, Carl Lear could never quite remember how his fly rod wound up tucked beneath his arm that night—only the power still left in that big salmon as he locked his grip around the base of its broad thrashing tail and wrestled him, net and all, to shore.

For ten minutes the two of them lay there together in the dark, damp grass, and when Carl finally regained himself, the old fish was dead. By the time he got the salmon up the bluff, across the bridge and to the truck, he was pretty well exhausted.

In the years that followed, Carl seemed to alternate between pride and regret whenever he thought or spoke about that fish and how it had died, always ending up thinking or saying, “Well, he was a salmon . . . he was gonna to die anyway.”

It was as close to a resolution as he could ever come.

He must have told me the story a hundred times. It always seemed to get more intense with each telling, and I would have been perfectly within my rights to have eventually begun to question the voracity of the narrative.

But then I would look deep into Carl’s piercing blue eyes and finally up on his wall, and there it would be hanging—the incontrovertible proof of his tale, that big beautiful salmon, wistfully peering down from above with the faded old chartreuse streamer still stuck firmly in the corner of his huge hook jaw.

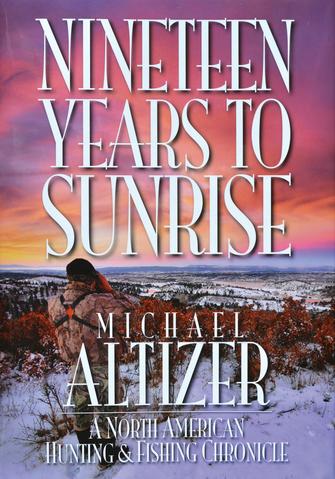

Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys. And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. By Michael Altizer Buy Now