When I first set out to photograph these splendid creatures in their natural element, I realized the need to develop my own special methods.

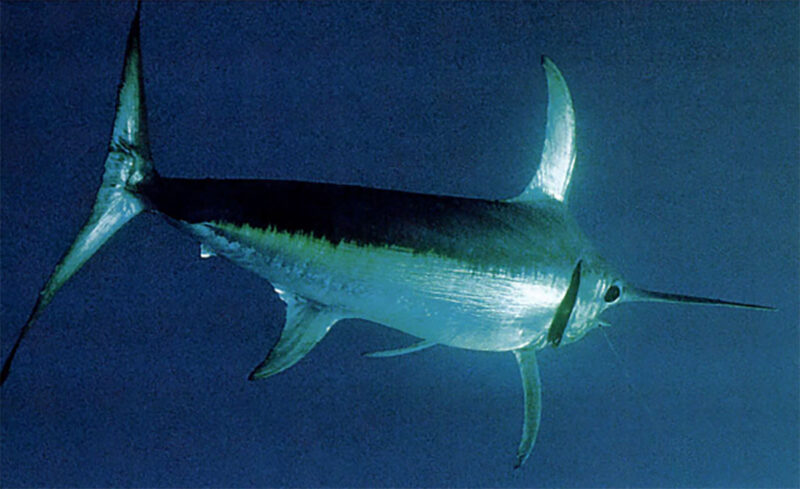

Broadbill swordfish

My heart was racing, my eyes wide in anticipation as the cloud of bubbles cleared… and there it was, silhouetted against the silvery surface. The striped marlin was racing straight at me, all fins erect, its neon blue tail lashing from side to side as it tried to overtake the trolled bait. The big fish swept past barely two feet overhead, its pectoral fins spread wide like a jet fighter. I fired off a whole roll of film in less than a minute as the200-pound fish charged the bait again and again and again.

For years I had experienced only the typical angler’s perspective: a dorsal fin, the tip of a bill, or the swirl of a dark shadow ghosting beneath a fast-trolled lure or bait. But here, right before me in living, glowing color, was a sight few have ever seen. And so it was that summer day in 1995, in the warm Pacific waters around Cocos Island some 300 miles southwest of Costa Rica, that I began my quest to photograph all nine of the world’s billfish species.

Billfish inhabit the tropical and sub-tropical oceans around the globe, yet they are among our most elusive creatures. Some species, such as the swordfish, blue marlin and sailfish, occur in each of our oceans. The Atlantic is home to white marlin, longbill spearfish and Mediterranean spearfish, while the black marlin, striped marlin and shortbill spearfish range throughout the Indian and Pacific oceans.

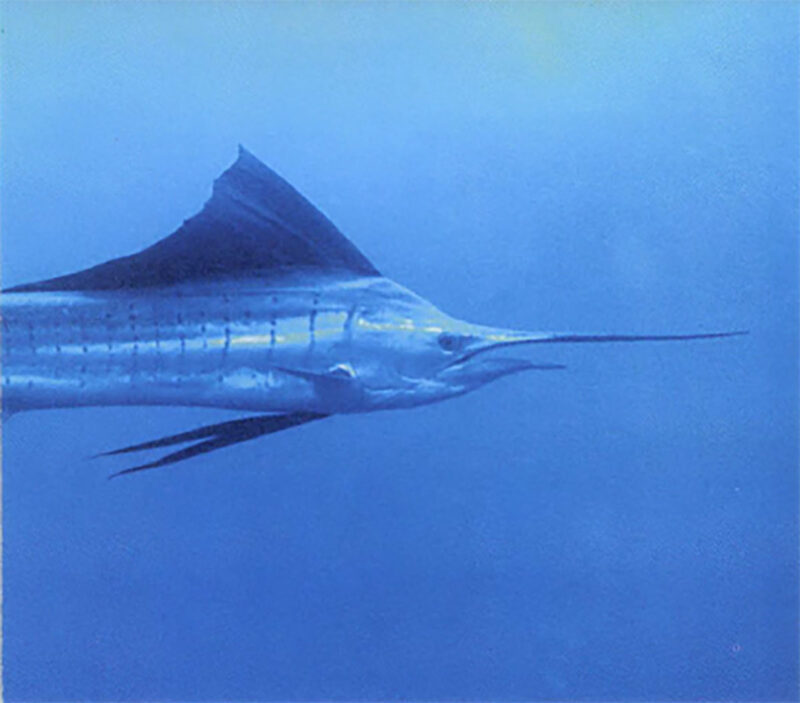

Pacific sailfish in normal cruise mode with pelvic fins retracted.

Billfish are among the largest of the teleosts (bony fishes); two species, the blue and black marlin , can exceed 1,500 pounds and 18 feet in length. All billfish have an elongated upper jaw and a long, bony rostrum, or beak, that may extend to more than a third of the body length, as seen in swordfish, or just barely protrude beyond the lower jaw, as in shortbill spearfish.

Most billfish live in the upper strata of our blue waters, often far from land. Blue marlin are not generally found in water cooler than 68 degrees Fahrenheit, but even in warmer waters they are able to maintain an elevated temperature in certain organs through a collection of blood vessels, called heat exchangers, located in the brain and around the eyes. This unusual adaptation is also found in other large, migratory species such as swordfish, tuna and lamnid sharks.

Marlin and sailfish are nomadic creatures that migrate thousands of miles from spawning to wintering areas. Blue marlin in the Atlantic, for example, have been known to cross and recross the ocean from the Ivory Coast of Africa to Brazil, all in a matter of months. Female billfish are “batch spawners,” which means they may have several batches of oocytes in the ovary at various stages of maturation. One female may release several million eggs in the presence of one or more accompanying males. I was lucky enough to witness seven male black marlin escorting a spawning female off the Great Barrier Reef in Australia. The group moved rapidly near the surface, riding the swells down-sea, the males jostling for position as the female shed her eggs. A charter boat crew in the same area once saw a spawning group containing three large females and 20 male black marlin.

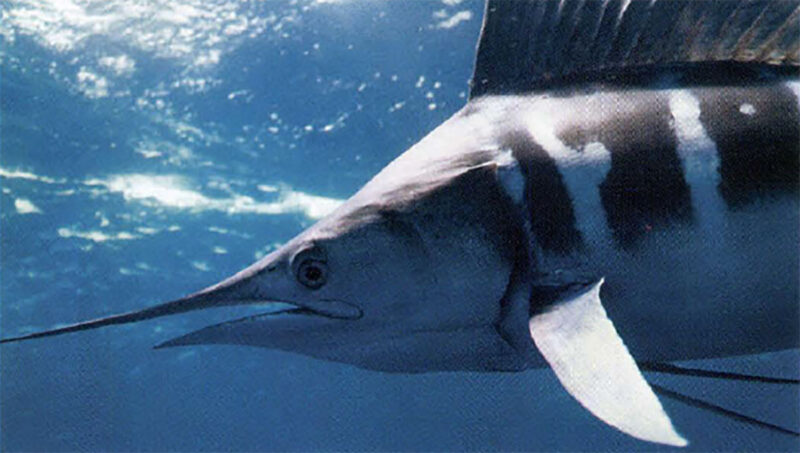

Atlantic sailfish.

Once the eggs are fertilized, they are left to drift in the plankton. The eggs, which hatch in 24 hours, are consumed by a number of microscopic predators, and the mortality is high.

Like all billfish, blue marlin grow rapidly, reaching a total length of almost seven feet in their first year of life. Males may reach sexual maturity in their second year and females typically in their third. There is also a pronounced difference in growth between the sexes. Male blues rarely exceed 220 pounds, while the largest females may weigh a ton or more.

Compared to the blue, the black marlin has a much larger head in relation to its body. All other marlin, sailfish and spearfish can fold their pectoral fins against the body, but those of black marlin are fixed and stiff. Black marlin can frequently be found in shallow coastal waters, while blues prefer clean, deep water.

400-pound blue marlin.

White and striped marlin look similar and share many of the same characteristics. The most easily recognized difference is that whites have rounded lobes on their dorsal, anal and pectoral fins, while those of striped marlin are pointed. There is, however, considerable variation in fin shape among both species. For example, the hatchet marlin, a variation of the white, has square dorsal and anal fin-tips. Whites rarely exceed 150 pounds and striped marlin, 400.

Spearfish are closely related to white and striped marlin. These long, thin fish typically weigh from15 to 40 pounds, and have not been well studied because they are so rare. For reasons still unknown, spearfish concentrate in certain waters at certain times of the year. For example, a sport fishery has developed for shortbill spearfish in the waters off Kona, Hawaii, during the spring.

Sailfish are the most prolific of the billfish and the most accessible to anglers worldwide. They vary considerably in size, with Atlantic sails typically weighing from 45 to 45 pounds, about half the size of their Indio-Pacific counterparts. These fish are named for their tall dorsal fin, or sail, a soft, supple membrane supported by spiny rays.

An excited white marlin.

Sailfish often form into schools when feeding and will raise their broad sails to help corral baitfish. When cruising, only the anterior portion is visible, while the rest of the sail is tucked into the dorsal groove. Sometimes the fish will retract it completely, such as when the fish they are accelerating to capture prey or when free-jumping.

The swordfish has the widest and longest bill, which may total a third of its body length. Unlike other billfish, they lack pelvic fins, and their dorsal, anal and pectoral fins are fixed. Swordfish also have a large caudal keel on each side just ahead of the tail, as do tunas and lamnid sharks. Not much is known about their behavior, even though they occur in all of the world’s oceans. During the day they typically remain at depths of 300 feet or more, but in temperate climates, swordfish will swim at the surface to warm their bodies and can occasionally be seen “finning out,” with their dorsal and tail fins completely exposed. Males seldom weigh more than 200 pounds, while females can reach 500 or more.

To study billfish in nature, one must obviously have a strong love of the sea and be willing to spend countless hours searching for them. First as a biologist and now as a full-time artist, I have been able to invest the time it takes to understand billfish behavior, anatomy and locomotion.

A remarkable close encounter with a free-swimming striped marlin .

When I first set out to photograph these splendid creatures in their natural element, I realized the need to develop my own special methods. There were few opinions available as to how billfish would react in the company of a diver and most were by no means encouraging. I was apprehensive about jumping off a boat to photograph free-swimming fish armed with a long, deadly bill and weighing a thousand pounds or more. But the time, the place, the conditions and the fish all came together on that first expedition to Cocos Island aboard the legendary sportfishing boat Hooker, captained by Trever Cockle .After successfully recording my first photographs, I vowed to return.

Prior to my second expedition to Cocos, I mapped out a strategy: to troll hookless teasers, then once we “raised” a fi h, stop the boat so I could jump overboard while the two mates cast hookless belly strips from tuna to keep the big predators close. Generally, this plan worked well. Several times I had fish swim within a few feet of my lens, and over the five-day expedition, I was able to photograph dozens of striped marlin and sailfish, though only one blue marlin.

Over the past four years I have captured eight species on film, the largest a thousand-pound blue marlin. Most of my photographic expeditions have been to places where bill fish are fairly numerous and where several species could be found at the same time, such as the fertile waters of the eastern Tropical Pacific, particularly off Panama, Costa Rica and little Cocos Island. In the Atlantic, Venezuela has similar conditions and opportunities for encounters, as do waters in the Cape Verde islands and the Azores.

A hungry striped marlin pursues a strip-bait teaser off Cocos Island.

Every time I roll into the water and the bubbles clear, exposing a 12-foot-Iong rampaging billfish with fins erect and stripes aglow, I find myself charged up by the thrill of the chase. A big marlin will swoop by only a few feet away, giving me hardly a second glance in its haste to overtake the teasers. They are so graceful. fluid and mesmerizing that on several occasions I have failed to notice sharks or giant tuna swimming within a short distance of me. In the Azores, white marlin are so numerous that I would often be surrounded by six or eight fish, a breathtaking kaleidoscope of color and movement.

Billfish are among the fastest animals in the ocean. In bursts over a short distance, they have been clocked at speeds up to 60 miles-per-hour. Marlin are particularly swift and agile, capable of executing a 360-degree turn almost instantaneously, then accelerating to an almost unbelievable speed with a single beat of their powerful tails. I’ve seen them suddenly materialize from a depth of 60 feet or more to engulf the bait in a shower of spray at the surface. I’ve also watched hooked marlin and sailfish rocket upwards to catapult high above the waves. Seconds later the fish comes crashing back down, its dark form silhouetted against the light and shrouded in crystalline bubbles. It’s all very surrealistic like dropping a huge ball of mercury on the floor.

After grabbing a bait, marlin and sails usually swim downward a short distance before stopping to turn the fish in their mouth. Billfish almost seem to tremble as they crush the bait’s head, turn it without ever letting go and then swallow it headfirst.

800-ponud blue marlin.

On a number of occasions we photographed marlin hitting a teaser five or six times; other times they ignored it completely. Whether they were simply not hungry or had some memory of a previous encounter with boats is not known. It is impossible to study these great fish in a captive situation in order to determine their intelligence and the extent of their learning. Surprisingly, most free-swimming marlin I have observed were not concerned about the presence of our boat or the divers. On the other hand, when hooked and fighting the line, they seem traumatized, and their movements become frantic and erratic. At such times, they are difficult and dangerous to approach.

In hot pursuit of a bait, most billfish undergo a dramatic color change. The body appears black, but the fins glow florescent blue against the dark-blue ocean background. To a greater or lesser degree, nearly all billfish have stripes running down their sides. Blue marlin often display vivid purple bands while circling and looking for something to eat. When white marlin become excited, their pectoral and tailfins “light up,” as does their broad, conspicuous stripes. From my observations, sailfish remain a dark brown or black overall, though the head may briefly turn an electric blue. Color changes can also be associated with the pairing of males and females in spawning season. Black marlin in the western Pacific turn florescent blue from bill to tail when pairing and courting.

When accelerating to intercept a bait or teaser, blue marlin fold down their pectoral, dorsal and anal fins, becoming, in effect, a sleek projectile. But when attacking a bait, marlin and other billfish erect their fins, which is essential for making high-speed turns.

Guy Harvey uses his remarkable underwater photographs as reference for creating dramatic paintings of billfish, such as this black marlin in Beastmaster.

An excited sailfish is particularly impressive with its sail fully erect and its broad pelvic fins angled downward. The dorsal fin ripples through the water, though it doesn’t flap, nor does it appear to impede the fish’s speed. Sails are the epitome of grace. When feeding in groups, they perform an underwater ballet this is truly unforgettable.

Billfish nearly always grab prey species in their jaws, though they will use their beaks to stun baitfish as well as to impale larger prey species such as tuna. The beak is also used in defense. Marlin bills have been found imbedded in sharks and other large fishes that eat juvenile and adult billfish — even in the hulls of fishing vessels.

Billfish prey upon tunas, bonitos and a variety of baitfish and cephalopods, and in some waters, squid form a large part of their diet. Occasionally we’ve found rare deep-water species such as scabbard fish and lantern fish in the stomachs of bill fish. Big marlin have been known to consume whole tuna, and white marlin and sailfish weighing up to 150 pounds. On a recent diving expedition at Cape Verde, we filmed a 400-pound blue marlin grabbing and gulping down a 15-pound yellowfin, then come back looking for more. Strangely, I have examined some 2,000 stomach samples from blue marlin in the Caribbean, and I have yet to find a flying fish, which is one of the most common baitfish in the region.

Recreational angling for billfish began in the early 1900s when fishermen with the Avalon Tuna Club at Catalina Island caught striped marlin and swordfish off the southern California coast. The sport was popularized in the 1920s and ’30s by American anglers such as Zane Grey, Michael Lerner and, of course, Ernest Hemingway, whose famous novel The Old Man and the Sea revealed the power, endurance, stamina and beauty of the blue marlin to readers around the world.

The recreational angling community has since adopted a self-imposed policy of catch and release. As a result, about 90 percent of all billfish are released, and based on recent studies, they have an excellent chance of surviving.

But sport fishermen are not the only ones who pursue these remarkable animals. Swordfish, prized for their firm white meat, are a major target of offshore fishing fleets. Originally, big swordfish were taken by harpoon as they basked on the ocean surface; today, the vast majority are caught by long-lines. ln one operation, a vessel may set out 60 miles of line with thousands of baited hooks which take both juvenile and adult swordfish. In most warm-waters areas, the catch of juvenile swords greatly outnumbers that of adult fish.

Black Marlin.

Long-lines are now deployed throughout the world’s oceans, primarily for tuna. Unfortunately, several species of billfish inhabit the same environments. Billfish are an esteemed food fish in several Asian nations and represent a major commercial fishery. Although Atlantic-caught billfish cannot be sold in the United States, there is a strong domestic market for fresh and smoked Pacific billfish. Because of increased fishing pressure on all pelagic species, the outlook is not good for billfish. In the Atlantic, current stocks of blue and white marlin are less than 25 percent of what they were 20 years ago. Swordfish numbers in the North Atlantic have declined even further. All three species were recently listed as being overfished by the US National Marine Fisheries Service.

Managing the billfish resource presents an unusual challenge for national and international fisheries interest groups. Because of the migratory habits of billfish, the actions of one country can directly affect the fishery of a nation clear across the sea. There is no doubt that billfish populations worldwide are stressed by overharvesting. The recreational fishing fraternity quickly realized that these beautiful gamefish are far too valuable to be caught only once. It’s time for all nations who utilize this priceless resource to work together to carefully manage our billfish, so that future generations of fishermen, photographers and artists can enjoy these magnificent fish.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared int the 1999 July/August issue of Sporting Classics.

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now

The Greatest Fishing Stories Ever Told is sure to ignite recollections of your own angling experiences as well as send your imagination adrift. In this compilation of tales you will read about two kinds of places, the ones you have been to before and love to remember, and the places you have only dreamed of going, and would love to visit. Whether you prefer to fish rivers, estuaries, or beaches, this book will take you to all kinds of water, where you’ll experience catching every kind of fish. Buy Now