“The subject of my art is a look, not a story.”

The Artist

If Eldridge Hardie had his druthers, this would be among the shortest articles ever written. It’s not a matter of being publicity-shy, or of wanting to cultivate a certain “arty” image, or of being even remotely difficult in the way that some highly accompli shed people can be – you know, the legend-in-their-own-minds type. On the contra ry, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone more down-to-earth than Hardie, anyone less likely to exude even the faintest whiff of self-importance. To paraphrase the old chestnut that coaches have been proffering ever since David beaned Goliath , he puts his pants on one leg at a time, just like the rest of us. And he’d be the first to tell you that.

No, the deal with Eldridge Hardie is that talking about his art makes him as fidgety as a bony-butted kid on a hard church pew. He’s not given to long-winded (and generally dubious) technical dissertations, the way some painters are, and if you ask him to explain his purpose in doing a particular piece, you’re liable to wait a good long time before getting a reply In fact, he’ll probably take it as a sign that. by his reckoning at least. the painting has somehow failed to deliver. (It could also simply mean that the person asking the question is a numbskull. but Hardie is too polite, too inclined to give the benefit of the doubt. to be that dismissive)He would vastly prefer that his art speak for itself; in his view, the first — and last — thing he should need to say is Look at it. To say anything more is to risk “contaminating” the viewer’s personal response.

“It’s not supposed to be a narrative,” Hardie shrugs. “If anything, it’s more like poetry. I’ve been doing this for 30 years now, and in that time I’ve learned how important it is to keep it simple, to eliminate the non-essential stuff and, above all, to focus on making a strong visual — and therefore non-verbal — statement.”

“It’s not supposed to be a narrative,” Hardie shrugs. “If anything, it’s more like poetry. I’ve been doing this for 30 years now, and in that time I’ve learned how important it is to keep it simple, to eliminate the non-essential stuff and, above all, to focus on making a strong visual — and therefore non-verbal — statement.”

Or, as he told an interviewer for Atlantic Salmon journal a couple of years ago, “The subject of my art is a look, not a story.”

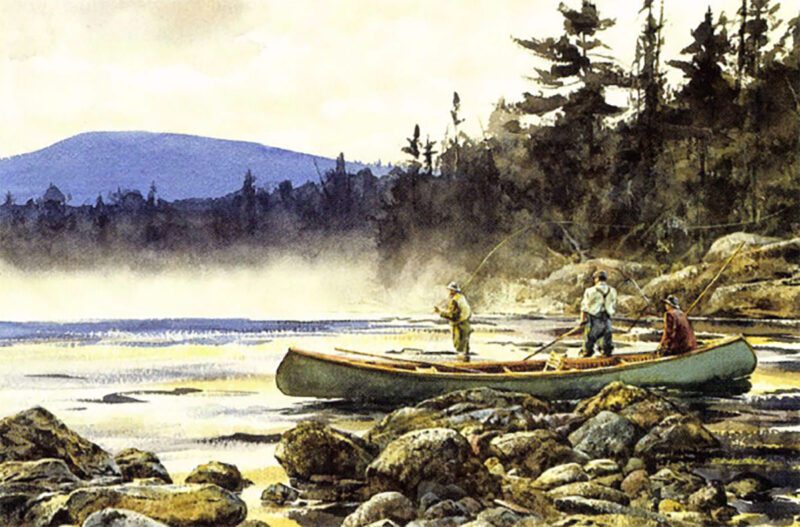

Miramichi Canoes is an exquisite testimonial to Eldridge Hardie’s status as one of America’s premier sporting artists.

And here you thought it was sinewy pointers making game in the tawny brooms edge, or drift boat fishing amid the breathtaking grandeur of the Rockies, or walking out at sunset with a Lab at heel and a rooster pheasant in hand, one finger crooked beneath its sharp, polished spurs In other words, the entire dazzling, ecstatic range of bird hunting and flyfishing. Little did you know….

You might think, too, that with a name like Eldridge Hardie — a classic sounding handle if there ever was one — he’d be a tweedy transplanted Brit or perhaps one of those wan New Englanders who can trace his roots all the way back to the damn Mayflower. That’s how I had him pegged when I first heard of him roughly 20 years ago, which seems to be about when everybody first heard of him. Trout Unlimited had selected Hardie as its inaugural Artist of the Year (“I was their guinea pig,” he laughs) and, largely on the strength of his imaginative “split level” depict ions of t rout in their environment, he’d gained an enthusiastic national following. “People would come up to me and say, ‘You’re the fish artist,'” he recalls.

Highland Grouse

Despite his patrician name and traditional artistic affinities, however, Hardie is no New Englander — far from it. Born in1940, he grew up in the West Texas town of (can’t you just hear the Marty Robbins song?), graduated with a degree in fine arts from Washington University in St Louis, and has called Denver home since 1996. And while those underwater scenes that secured his early reputation were perhaps a bit gimmicky in conception, Hardie’s execution, based on countless hours of observation and research, was flawless. They’re marvels, really, resourcefully designed and full of interesting touches, and they continue to be a source of delight for many Besides, no one ever said that art has to be deadly serious all the time, or that you can’t go out on a limb and experiment once in a while.

For Hardie’s part, although he says “you wouldn’t believe how time-inefficient those things were,” he acknowledges that they do have redeeming qualities. “They’re part of my history,” he notes, “and they were important to my development as an artist For what they are, they’re well-done.”

If nothing else, they gave him the exposure he needed to get his career firmly on track. It wasn’t long before the “fish artist” of the 1970s blossomed into one of the most respected, accomplished, and comprehensively skillful sporting artists of the contemporary era, with a long list of honors and awards to his credit. Hardie’s work has been exhibited in such prestigious venues as the National Museum of Wildlife Art, the American Museum of Fly Fishing, the Gilcrease Museum, and the William Secord Gallery, to mention only a few. It has also graced the covers and inside pages of countless art and sporting-related magazines As a writer — and especially as a writer who values the way his stories are designed and presented — it’s always a pleasure to discover that the editors have chosen a Hardie image to accompany my byline. His art makes me look good — and helps me read that way, too. If the poetry is lacking, his art makes up for it.

If nothing else, they gave him the exposure he needed to get his career firmly on track. It wasn’t long before the “fish artist” of the 1970s blossomed into one of the most respected, accomplished, and comprehensively skillful sporting artists of the contemporary era, with a long list of honors and awards to his credit. Hardie’s work has been exhibited in such prestigious venues as the National Museum of Wildlife Art, the American Museum of Fly Fishing, the Gilcrease Museum, and the William Secord Gallery, to mention only a few. It has also graced the covers and inside pages of countless art and sporting-related magazines As a writer — and especially as a writer who values the way his stories are designed and presented — it’s always a pleasure to discover that the editors have chosen a Hardie image to accompany my byline. His art makes me look good — and helps me read that way, too. If the poetry is lacking, his art makes up for it.

In fact, I can’t think of another artist of Eldridge Hardie’s stature who maintains such a high profile as an illustrator. Much of this is admittedly “passive,” in the sense that he allows magazines to reproduce pre-existing images, but he continues to do original illustrations as well. His specialty in this regard is providing exquisite pencil drawings for books; among the recent titles to feature his work are Pick of the Litter by Bill Tarrant, Shotguns & Shooting by Michael McIntosh, Worth Matthewson’s Reflections on Snipe (the deluxe limited edition included an original Hardie etching as well), and a reissue of Ortega y Gasset’s Meditations on Hunting by Wilderness Adventures Press.

Goose Hunter

“I like to draw,” Hardie explains, “and as a reader I’ve always enjoyed and appreciated illustrations. Plus, it gives me an opportunity to change gears from painting But I don’t allow authors or publishers to give me a ‘laundry list’ of subjects to illustrate. Instead, my method — which is essentially what the great illustrators of the 1920s and ’30s did — is to read the text and pick out subjects that are not described in detail.”

Indeed, it would probably be more accurate to describe Hardie as an embellisher rather than an illustrator. Case in point: One of his drawings for the recent Country sport anthology, Pheasant Tales, is an absolutely stunning rendering of a booming prairie chicken cock, tail erect. horn-like pinnae extended, neck sacs inflated. I swear you can almost hear the bird’s eerie, squalling calls, and I should know I’m gazing at the original as I type this. Needless to say, it’s among my most treasured and irreplaceable possessions.

Redfish Flats

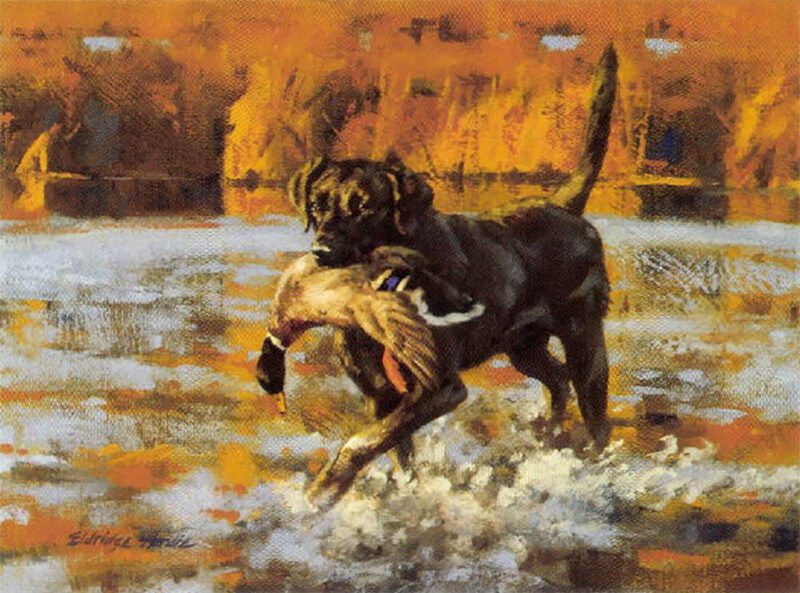

Hardie’s ability as a draftsman is further reflected in his wonderfully realized depictions of bird dogs, a subject with which he’s become closely identified in the past decade or so. He has a tremendous feel for their intensity and athleticism, and he allows their pride and character to shine through. Like such great dog artists of yore as William Harnden Foster, AB. Frost and JM Tracy, Hardie doesn’t impose his own ideals of beauty on his canine subjects. Nor does he consciously distort them to suit his own purposes, the way Osthaus and Rosseau did. If his birddogs have a “heightened reality,” it’s because he alloys his artistic fidelity with personal admiration.

“I do like dogs,” Hardie confesses. “They’re a joy to work with, and they’re athletic marvels, the end products of countless generations of selective breeding And of course they’re terrific subjects to me, because of my strong interest in figure structure. Take an English pointer, for example. Everything shows, right down to the individual muscles. One of the things I occasionally do to keep myself ‘sharp’ is go to the Denver Art Students League and draw or paint a model from life It’s not for everybody, but for me it translates into better, more confident paintings of dogs.”

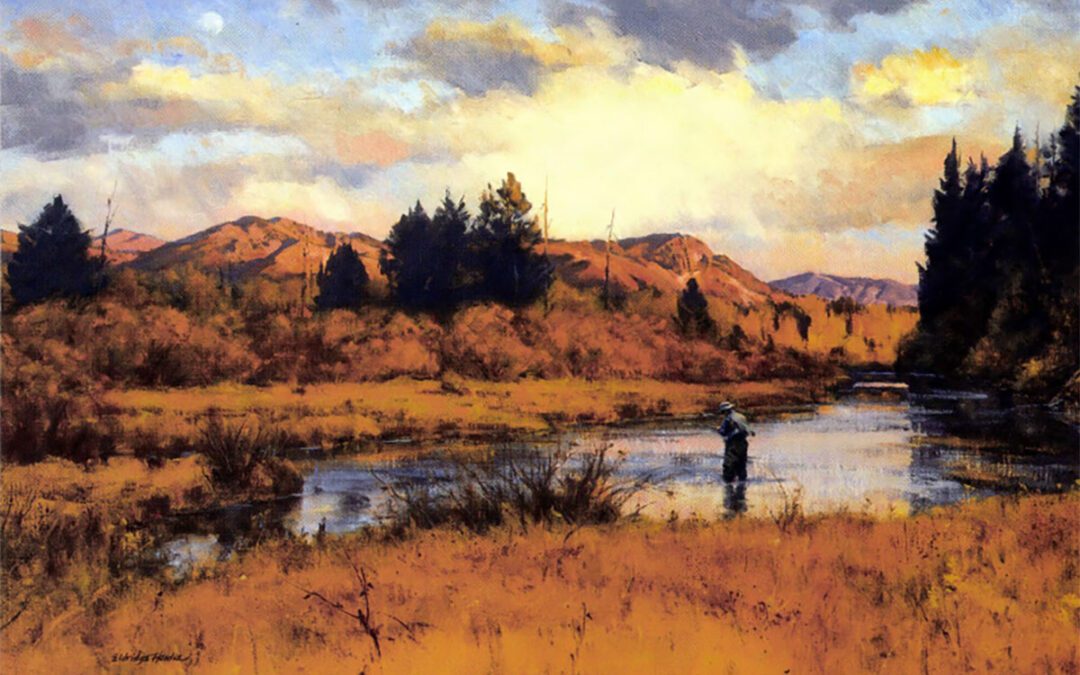

River Rhythms, a 14 x 22 water-color, depicts a classic salmon-fishing scene on the Miramichi River in New Brunswick.

Another pictorial element showing up in Hardie’s paintings with increasing frequency is a boat of some kind, usually either a timelessly elegant wood-and-canvas canoe or adrift boat with its rakishly upswept lines. “I think I could sell a landscape with a boat in it to anybody.” he muses. “The ‘non-sporting’ people, especially, really seem to respond to those paintings. For that matter, so do I. Not too long ago, I did a simple little watercolor of two canoes pulled up side-by-side onshore. It was almost like a still life. I called it Miramichi Canoes, and I liked it so much that I couldn’t bear to it. It’s hanging in our living room right now.”

Whatever Eldridge Hardie paints — and whether he opts for the spontaneity and lyricism of a watercolor or the range of effects that oils permit — he stresses the importance of being there, of immersing himself in the experience and the environment, of gaining the knowledge and insight that underpins all enduring art. Although he admits that it’s “not always practical,” he makes a point of doing as much on location field sketching and study painting as he possibly can. He takes photographs, too — they’re immensely helpful for “filling in” the details — but he filters and corrects the information they provide by comparing them with his own observations.

“The thing you have to remember about photographs,” Hardie notes, “is that they’re not real. They’re approximations. A photograph taken with Fuji film, for example, looks very different from one of the same scene taken with Kodak film. why there’s no substitute for looking at a scene with your own eyes and putting it down as you see it. It brings something to a painting — I guess you could call it authenticity that you just can’t get any other way. If you haven’t stood out there and made those decisions, both as an artist and as a sportsman, you can’t really know how to do it, or how it’s supposed to look.

“The thing you have to remember about photographs,” Hardie notes, “is that they’re not real. They’re approximations. A photograph taken with Fuji film, for example, looks very different from one of the same scene taken with Kodak film. why there’s no substitute for looking at a scene with your own eyes and putting it down as you see it. It brings something to a painting — I guess you could call it authenticity that you just can’t get any other way. If you haven’t stood out there and made those decisions, both as an artist and as a sportsman, you can’t really know how to do it, or how it’s supposed to look.

“I was quail hunting in Kansas a couple months ago, and while I was there I did half-a-dozen field studies. They probably won’t all develop into finished paintings, but the important thing is that I was able to get the ideas down while they were ‘hot.’ There’s nothing like getting an idea and really nailing it.”

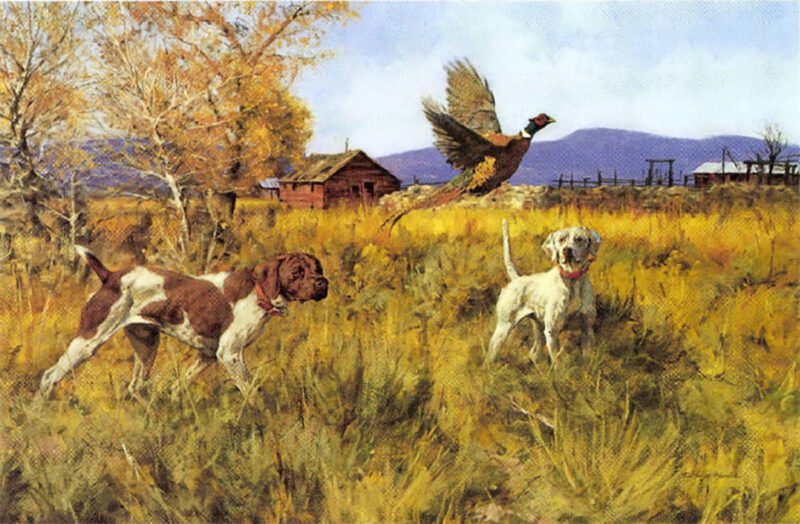

Montana Standard Time, a 24 x 36 oil, relives an exciting moment from a prairie pheasant hunt.

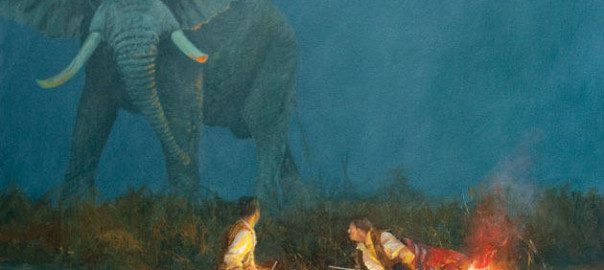

Not that Hardie suffers from any shortage of ideas. Within the past year or so, his art has taken him from the Arizona desert to the Scottish highlands, from the flats of Abaco to the piney woods of the Georgia-Florida plantation country. On the surface, you might think that painting, say, an anglers talking tailing bones in the mangroves would demand a different set of skill s and sensibilities from painting red grouse flushing from purple heather. But Hardie professes to have no trouble shifting gears in this respect. By the same token, he also has an amazing facility for capturing both the dramatic, exciting, “active” aspects of hunting and fishing and the quiet, poignant, introspective ones. To my way of thinking, this ability to embrace the whole of the sporting experience is the ultimate testament to his achievement.

“It’s all good subject matter,” he emphasizes. “No matter where I am, there’s always a visual payoff — and that’s always what I’m looking for.”

Marsh Dog, a 12 x 16 watercolor, captures a spirited black Lab doing what it does best.

As a boy who grew up devouring the outdoor magazines of the day (the way we all did). Eldridge Hardie used to admire the illustrations of John Scott and Bob Kuhn and think to himself ‘Wow — wouldn’t that be a great job?’ Years later, when he was first getting his feet under him as a professional artist, he concluded that what he really wanted to paint were the things he was passionate about. And while there were the customary dues to be paid, he’s never looked back. In every sense, he’s one of the lucky few who’s truly living out his childhood dream.

He takes nothing for granted, either — especially since he and his grown son, Tom (“My main hunting and fishing partner”), have recruited an “apprentice” in the form of Hardie’s 12-year-old neighbor. “He saw me throwing dummies for my Lab,” Hardie recounts, “and came over and started asking questions. He was obviously really interested in hunting and fishing, and because there’s no dad at home, Tom and I just sort of took him under our wing. He’s gone trout fishing and duck hunting wit h us, and it’s been as neat for me, I think, as it has been for him. It’s helped me see through fresh eyes, and it’s reminded me how much it all means.”

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now