Larry Norton’s subjects are not only anatomically proportionate but portrayed in body positions as they appear in the wild. One notes the malevolent cast of a lurking croc, the rubble of scattered bones, virtually hears the forlorn call of the turtle dove. Terror amidst incredible beauty. The real Africa.

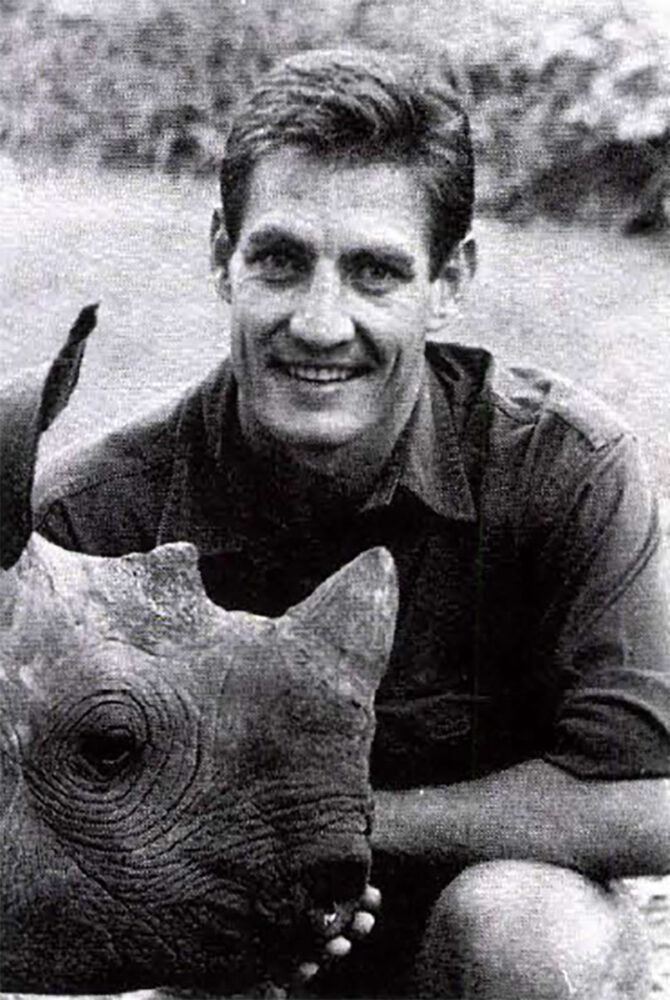

Norton and young black rhino.

I had the good fortune to meet Larry Norton for the first time on his trip to the states. Looking like a rugby player in dress clothes, he greeted me at New York’s exclusive Leash Club on the upper east side. Over lunch, we discussed his family’s farm in Zimbabwe, his wife Sara and their three children, hunting, American politics, fishing, wine, my first safari, the world soccer cup, rainfall, the traffic in New York and the last wars for his country and mine.

After dessert and coffee, we finally got around to looking over some of his paintings. Unfamiliar with his work, I was astonished. In an instant it was clear to me that this vibrant, engaging young man (still in his 30s) with his impeccable manners and charm is not only a superb painter, but well on his way to becoming one of the foremost wildlife artists of our time.

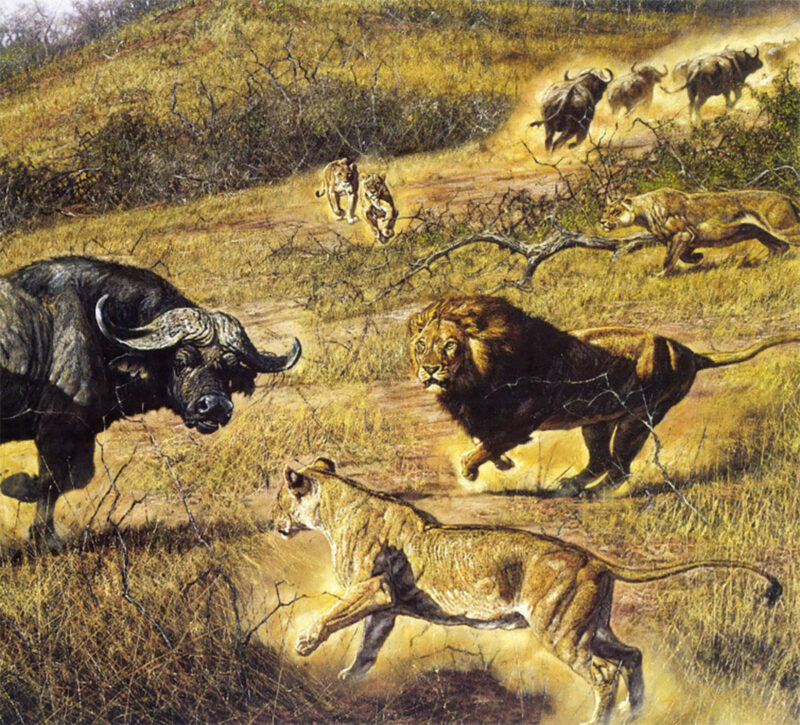

Countless hours of studying and sketching lions throughout southern Africa has enabled Larry Norton to portray the big cats not only accurately but in a variety of dramatic situations, whether on the attack as in The Kill.

At age two, Larry began to etch figures in the dust around Dahwe, the family farm. Situated in Mvurwi, a rich agricultural region 100 kilometers north of Harare, the area abounds with the plains game that provided Larry with his initial subject matter. On holidays the Nortons would travel to the Zambezi Valley to hunt and fish. There, camped among the scary stuff, young Larry learned his respect for wildlife. Certainly, there were other dangers in growing up in a country at war. In the mid-70s the fighting forced the family to change its plans more than once but their outings were never curtailed.

Through his schoolyears , Larry continued to draw and paint, but it was always assumed he would continue to work his family’s land. After spending four years in Australia to study agriculture, he returned home with his degree but had discovered a very basic truth — that he wanted to spend his life painting.

“I talked with my father, a practical man, who understood completely but informed me that from that point forward I was on my own,” Larry remembers.

“I talked with my father, a practical man, who understood completely but informed me that from that point forward I was on my own,” Larry remembers.

We aficionados of art and wildlife are grateful as much of Larry Norton’s work is truly inspiring. His animals appear natural and unaffected because he courageously avoids sentiment and the slightest inclination to impose any human-like countenance. In his African National History Series: The Big Five, I especially like his painting of a black rhino for its sense of approaching season. The subject stands in the half-light of a tiny clearing. The ground is a mosaic of fallen leaves alternately light or dark where the clear autumn sun is blocked by the dense canopy overhead. Back in the thicket, twisted trunks of shorter trees catch the same periodic light. In various grays, the squat bulk of the rhino invokes a graceful yet sinister silence. All is still — for the moment.

Larry credits his five months with Simon Combes in England for having the greatest influence on his work. “Among other things,” the artist recalls, “I learned a lot about considering oneself a professional painter.”

Lion in tranquil repose in The Kings.

It is the use of the brush, however, that distinguishes Larry Norton from his contemporaries. He seems to achieve greater visual effect with fewer brushstrokes.

“Ninety percent of my painting is done with coarse bristle brushes.” Impressive, when one considers the clarity he is able to achieve.

In a two-story studio he built on his family’s farm, the artist endeavors to bring his inspirations to canvas. There, on the top floor, he keeps a library of hundreds of photos and drawings he has made of his subjects -fruits of his many expeditions into the wild. Common to Larry’s work is an attention to detail, tromp l’oeil, where each butterfly, each savanna grass and acacia leaflet, evokes a genuineness that would win the assent of the most experienced African hunter.

Norton painted Fearful Symmetry after observing tigers in the jungles of India.

Larry, it seems, has always been consumed by what the late George Adamson called “The Searching Spirit.” After working a year as a whitewater rafting guide on the Zambezi River, Larry set out on a series of expeditions that would daunt all but the most intrepid. He hiked through Hwange, Chizarria and Gonarezhou National Parks in Zimbabwe. In 1991 pilot-writer Tom Clayton and Larry spent a year flying a single-engine Cessna across eighteen African countries. The long journey provided a plethora of images, both good and evil. There was the horrible aftermath of The Liberian War. Their plane was the first private light aircraft to land in Monrovia since the battles. With the surrounding area still held by rebels, Larry and Tom saw the mass burial graves beyond the runway where 21,000 human skulls had been heaped – revolting to any civilized man, indeed so to the African artist. Yet, the trip surrendered a desolate beauty, which Larry eloquently described in his diary after flying The Niger River north to Timbuktu:

“The Sahara itself threatens to devour the town. Insidious winds drive legions of dunes down the streets and doorways slowly submerge … Images of this place stay with one … The entire sky a dull sepia orange with dust … Dunes by moonlight … tortured acacias, like mourners. Rusty carcasses of valiant voyages still bearing their logos of hope — Paris-Dakkar Trans Africa Expedition, Japanese Exploration Team.”

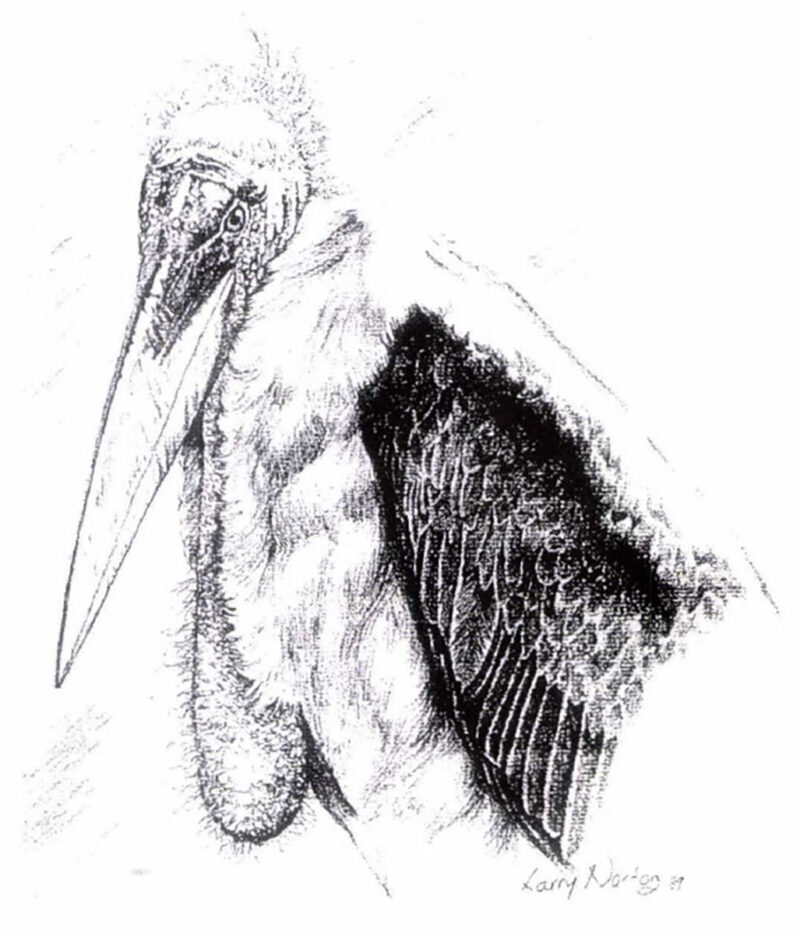

Evil Eye will always remind Norton of his visit to war-ravaged Liberia in 1992. “We found a mound where thousands of human skulls had been buried. It was a grim

look into Africa’s darkest side.”

And finally, over Namibia, the artist wrote: “Springbuck, wildebeest, giraffe race beside the plane … Etosha is magical abundance. Five black rhino and convoys of elephant water by night. Rapier horns … gemsbok, painted masks and strawberry coats against the horizon …ostriches disembodied by wavering mirages are swallowed by the hot distance.” Vivid, the scenes become more so through his artist eyes. He later describes his struggle for restraint. “There is still a long way to go. At times the inspiration becomes painful because the desire to attack large, serious canvasses has to be bottled until the journey is completed.”

Norton’s Sundance on Stone portrays an inquisitive leopard that had invaded his camp and chased off two of his horses.

More recently Larry was part of a canoe/kayak trek that followed the course of the Zambezi River from source to mouth, a distance of 1,675 miles. A later expedition enabled him to explore the Zambezi through Mozambique and on to the unique coastal island of Bazaruto. Just before our meeting in New York he had spent two weeks in the Himalayas trying for a glimpse of the elusive snow leopard. Unfortunately, snowstorms prevented him from traversing a certain high pass, but he was able to find bharad, the blue sheep and principal prey of snow leopards.

Such first-hand confrontation is evident in his work. Nothing is faked. Larry underscores the fallacy of an artist simply driving through a game preserve or relying solely on photographs. “Perspectives are often distorted by the lens,” he explains, “and the tendency is to accentuate the head, eyes or facial expression.”

Such first-hand confrontation is evident in his work. Nothing is faked. Larry underscores the fallacy of an artist simply driving through a game preserve or relying solely on photographs. “Perspectives are often distorted by the lens,” he explains, “and the tendency is to accentuate the head, eyes or facial expression.”

Larry Norton’s subjects are not only anatomically proportionate but portrayed in body positions as they appear in the wild. All are from real or near-real encounters. Having more than once walked up on the remains of a leopard-killed baboon, he was able to recreate the scene from the surrounding tracks of other baboons who must have watched in horror. He has been criticized for an occasional gloomy or nefarious element in some paintings, but insists he is only trying to paint the scene as it actually happened. One notes the malevolent cast of a lurking croc, the rubble of scattered bones, virtually hears the forlorn call of the turtle dove. Terror amidst incredible beauty. The real Africa.

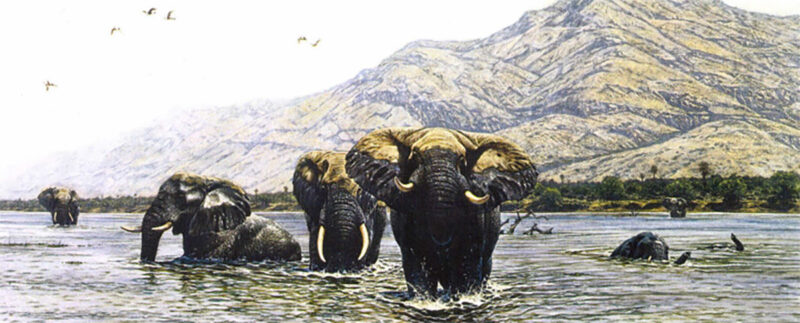

Bull elephants cross the Zambezi River in African Epic.

A fellow of the Royal Geographical Society, Larry Norton has earned international acclaim. He was presented with the Society of Animal Artists’ highest award, the Catasus Medal, in 1989. One year later, age 27, he won Safari Club International’s inaugural art show with Afternoon Kill, an oil of a leopard guarding its kill.

There is tendency among animal artists to over emphasize their subject, often at the expense of background. In virtually all Larry Norton’s art, removing the principal subject would still leave a painting both compelling and authentic. In even greater accomplishment, he not only depicts multiple subjects but draws on their interaction. While there is always the risk of different species competing for the scene, his compliment each other successfully.

There is tendency among animal artists to over emphasize their subject, often at the expense of background. In virtually all Larry Norton’s art, removing the principal subject would still leave a painting both compelling and authentic. In even greater accomplishment, he not only depicts multiple subjects but draws on their interaction. While there is always the risk of different species competing for the scene, his compliment each other successfully.

One such piece, Parting the Waters, depicts an early morning meeting of predator and prey. A lion strides cooly across center canvas, having split a big herd of zebras. Stately, heavy-maned, the lion catches the new sun that comes to us through the still-rising dust. No less exalted by the light, the zebras stand transfixed, somewhat calmed by their number but watching the big cat’s every move. Overhead, a half-dozen birds hover, awaiting the next act which may be nothing -or everything. Each animal is affected by the other, colors alight in each’s version of dawn. Fred King of Sportsman’s Edge/King Gallery gave Larry his first exposure to the U.S. market and remains his principal agent here. “The feeling in much of his work is a richness of color and wonderful landscapes,” says King. “Larry puts an animal in a landscape rather than simply painting a photograph of one. He knows his animals. He puts 110 percent into every painting.”

One such piece, Parting the Waters, depicts an early morning meeting of predator and prey. A lion strides cooly across center canvas, having split a big herd of zebras. Stately, heavy-maned, the lion catches the new sun that comes to us through the still-rising dust. No less exalted by the light, the zebras stand transfixed, somewhat calmed by their number but watching the big cat’s every move. Overhead, a half-dozen birds hover, awaiting the next act which may be nothing -or everything. Each animal is affected by the other, colors alight in each’s version of dawn. Fred King of Sportsman’s Edge/King Gallery gave Larry his first exposure to the U.S. market and remains his principal agent here. “The feeling in much of his work is a richness of color and wonderful landscapes,” says King. “Larry puts an animal in a landscape rather than simply painting a photograph of one. He knows his animals. He puts 110 percent into every painting.”

Which is what one might expect from so adventurous a talent — this rising star of African art.

Peter Capstick has been hailed as the adventure-writing successor to Hemingway and Ruark. This long-awaited sequel to Death in the Silent Places (1981) brings to life four turn-of-the-century adventurers and the savage frontiers they braved. Buy Now

Peter Capstick has been hailed as the adventure-writing successor to Hemingway and Ruark. This long-awaited sequel to Death in the Silent Places (1981) brings to life four turn-of-the-century adventurers and the savage frontiers they braved. Buy Now