John Doyle sees the ocean as one of the last frontiers where man can test his courage.

John Doyle once showed me a photo from his boyhood in the mid-’40s. The picture was of him, standing next to a string of five largemouth bass that his father had caught on a fly rod and displayed, alongside his four-year-old son, for the camera to capture. The fish were larger than John and, in retrospect, indicative of his destiny.

John Doyle once showed me a photo from his boyhood in the mid-’40s. The picture was of him, standing next to a string of five largemouth bass that his father had caught on a fly rod and displayed, alongside his four-year-old son, for the camera to capture. The fish were larger than John and, in retrospect, indicative of his destiny.

Raised in the sleepy seaport town of Charleston in the ’40s and ’50s, John spent his afternoons after school at the marina or at the Battery looking out to Charleston Harbor, his feet hanging over the side of the sea wall, his head resting on a rail. “Those were my impressionable years,” he says now. “I’d sit for hours studying the boats. I knew every dock and every name of every boat. I could distinguish a Matthews from a Richardson. I could describe the military shape of a Fair-form flyer and recognize the streamlined glamour of a Chris Craft in the ’40s.

“Today, people ask me ‘Why do you paint fish?’ It’s always been the ocean for me, and it started with boats.

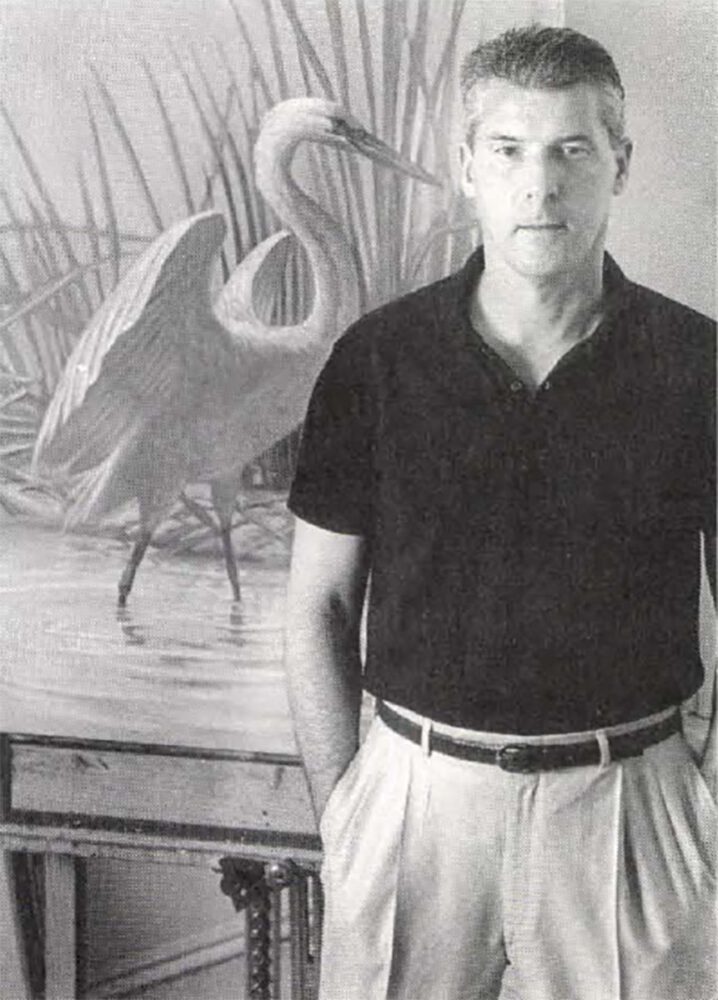

Charlestonian artist John Carroll

Doyle.

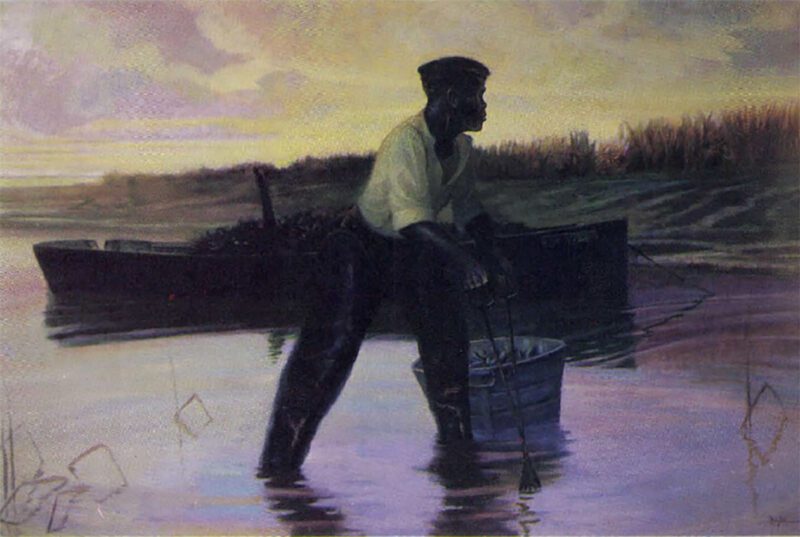

“In my teen years,” he continues, “I made money by delivering the News & Courier and Evening Post. Charleston was different then; you can’t imagine how very laid-back it was … dogs sleeping in the streets, cats curled up in alleyways. I can remember biking down lower Legare Street, emerging from the cool shadows of Charleston’s old homes. I remember purplish-grey shadows cast from Palmetto trees splashed across sandy, stucco walls in the late afternoon. I knew the shadows were not grey but shades of blue. I was aware of things: movement, color-the colors in a fish laid out on the wharf at the old marina and the fading of that color as it lay in the sun. I did not take the beauty of Charleston for granted, or of living near the sea. None of this was lost on me.”

I’ve known John Doyle for a number of years, since the 1970s when he was a young artist living in a $48 a month apartment on Queen Street and painting boats on commission for $150 a canvas. John could be found most evenings draped on a bars tool at Captain Harry’s Blue Marlin Bar in the market area. In fact, one of his first major works, his first gamefish, was a commission for Captain Harry’s.

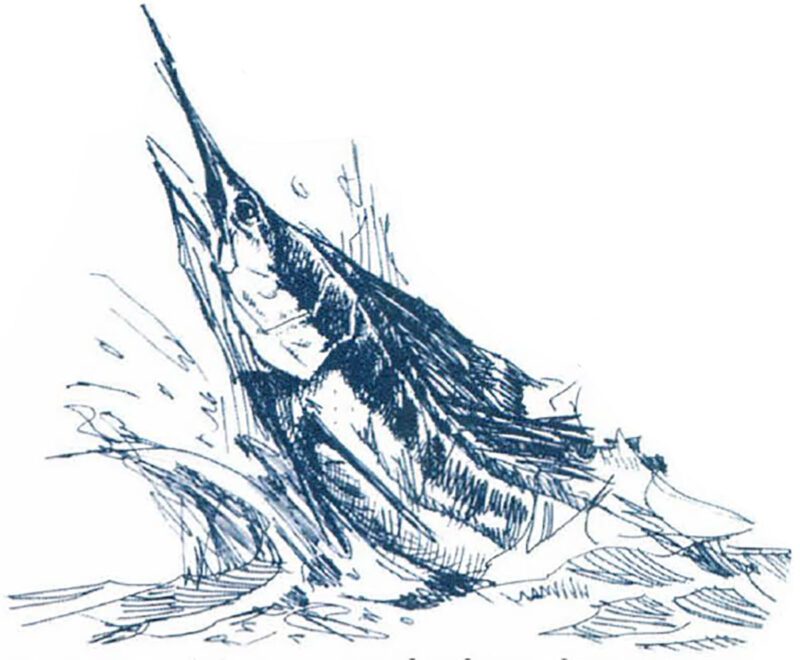

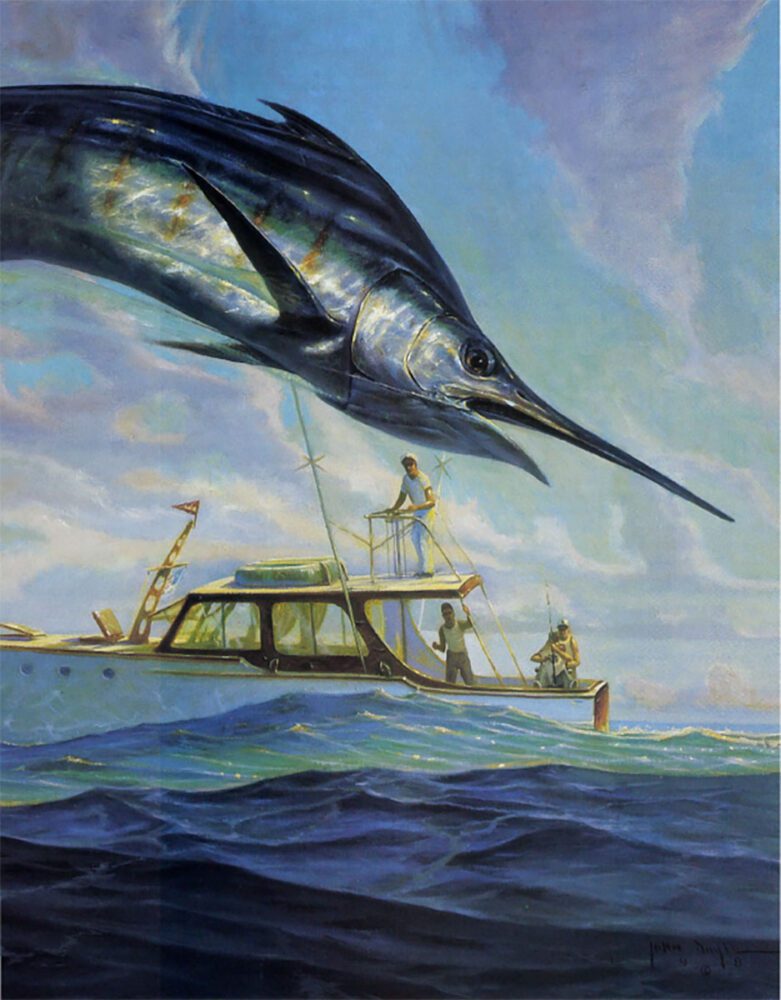

“Harry Cochran, who owned the place, wanted one of those real dramatic paintings of a blue marlin kind of jumping, in a three-dimensional sense, out of the water and coming right at you,” John says. “I had done some ocean racing and seen some billfish but I was unsure of their anatomy so I referred to an encyclopedia and checked out the local library and the state fisheries. I saw some taxidermy fish and thought, ‘There ain’t nothing to this.’ I said to Harry, ‘How much do you want to pay and when do you want it?’

“I made about $200 for the piece and could pay the rent for two months and drink and eat.”

The Joy of Sportfishing.

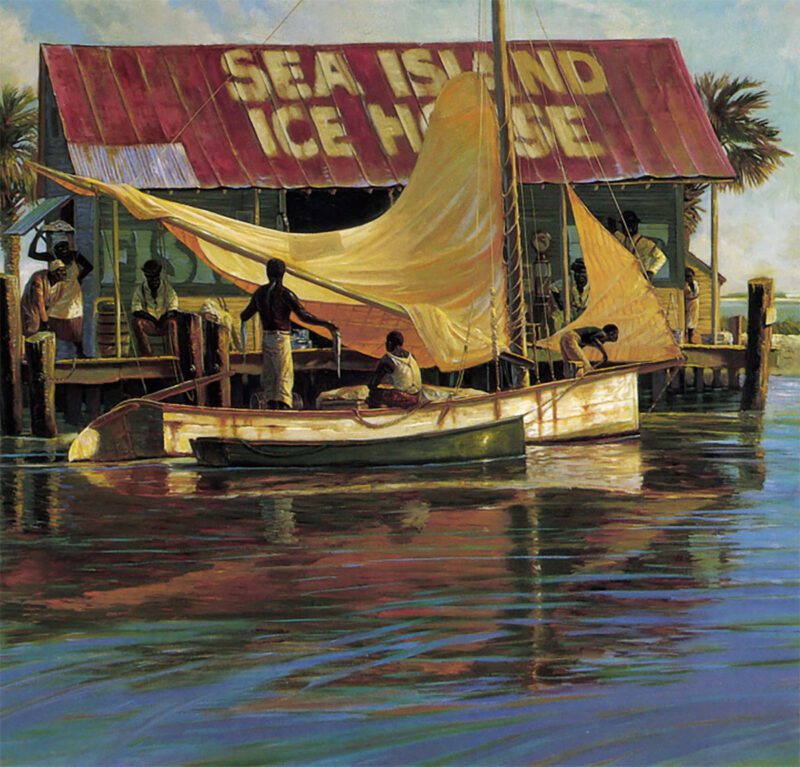

John was soon being hired to do larger commissions. His early paintings of black jazz musicians, pool players, and antebellum ladies in window seats still hang on the walls of Myskyn’s Tavern downtown. When Myskyn’s changed locations last year to a more upscale location, the John Doyles moved with them, as much a part of the tavern by now as its reputation for music. Through the years he has done commission pieces for many other establishments around the city, documenting Charleston’s colorful past and present: street vendors, ocean scenes, gamblers, regional black culture, commercial oystermen and shrimpers in the marshes of the Lowcountry, polo ponies, wild birds and saltwater fish.

“After that first billfish for Captain Harry I did a couple more,” he says. “And 10 and behold, some people saw them and I had orders for even more. The next thing I knew businessmen were approaching me and asking me if I would like to do some limited edition prints of saltwater game fish.

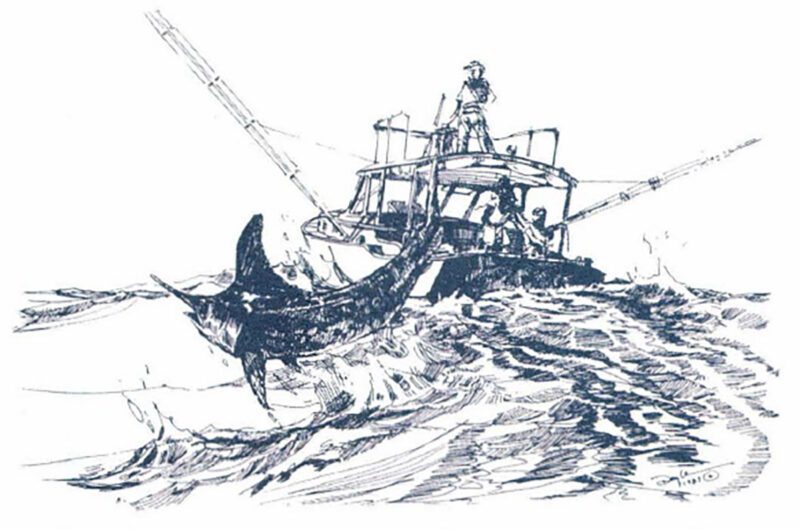

“I came to love the actions of fish leaping out of a rolling sea. As I got more into it I realized there are less than two dozen artists in the country painting saltwater gamefish. And in the wildlife market this is very, very rare. There’s so many hundreds of artists painting ducks and wildlife-related subjects. One reason artists stay away from saltwater gamefish is that it is difficult to see them jump. You have less than two or three seconds. Good photographs are hard to come by, and taxidermy fish do not give you a good enough idea of movement. I’ve taken videos, photographs, talked to fishermen, and studied fish for hundreds of hours. Also, I have an advantage inpainting the boats in some of these pieces. I know boats. I used to be a boat builder.”

Sea-Island Ice House.

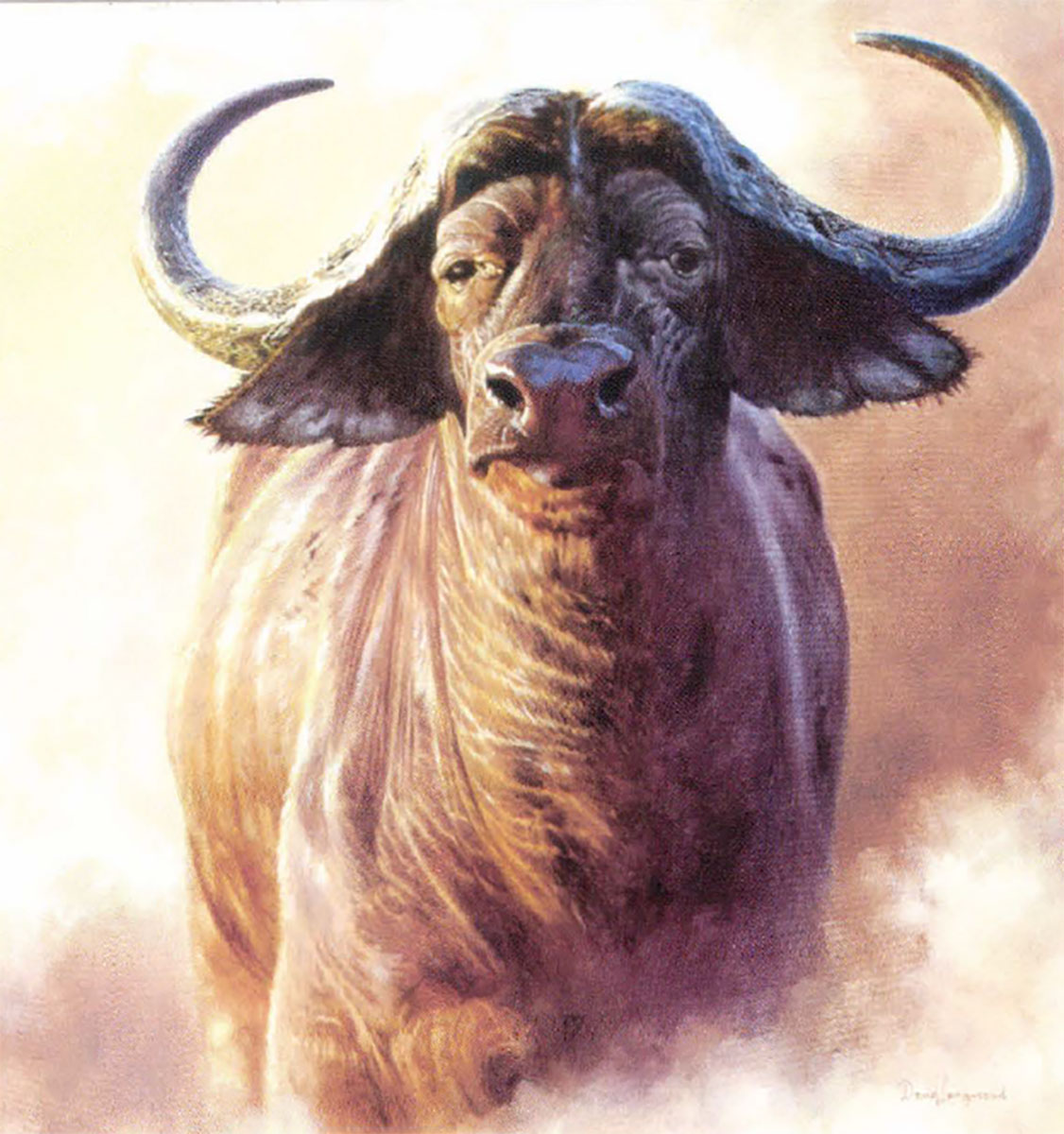

John sees the ocean as one of the last frontiers where man can test his courage. He says: “More sportsmen are moving toward game fishing because it fills the need big game hunting in Africa and India once filled. When I paint a saltwater fish, I am painting the spirit of fishing, reporting on that and the beauty of these majestic creatures that can flash color changes before your eyes. An excited marlin, for example, might glow in hues of red-orange to violet-blue. I also see in fish the grace of ballet movement. I capture that movement, action, color, and light.”

He is an impressionistic realist. “Light is important to me; that along with atmospheric perspective and color harmony are my three major concerns in a painting.” John works in oils, usually on large canvases. He recently shipped a painting to Vancouver, British Columbia which, in its frame, measured five-and-one-half by seven feet. His typical billfish painting measures40 x 54 inches and takes a month or two- sometimes longer to complete.

Most of his paintings reflect the angling adventures of other fishermen, like Broadbill Off Cuba, which depicts Ernest Hemingway fishing from his 38-foot wheeler, the Pilar. John doesn’t work directly from photographs but comes up with original ideas and puts them in sketch form. “I rework and rework the scene-the fish jumping to the left, to the right; I have hundreds of drawings where I’ve worked out their movement. Once I am happy with the sketch, I refine it and draw it with charcoal onto the canvas, then go from there.

“With every brushstroke you have to be aware of anatomy. I now have a large reference library in my studio and there’s not a day I don’t go digging through it. You have to have the accuracy of the fish, and the accuracy of the spirit and emotions of catching the fish.”

“With every brushstroke you have to be aware of anatomy. I now have a large reference library in my studio and there’s not a day I don’t go digging through it. You have to have the accuracy of the fish, and the accuracy of the spirit and emotions of catching the fish.”

But sometimes he is intentionally inaccurate. “I give the marlin human eyes,” he says. “The eyes of a marlin are blue and sometimes silver. I make them brown. I also do this with my thoroughbreds, my egrets. Someone once said all good paintings are self-portraits.”

It’s been 20 years since John began his career as a painter. Today, at 47, he is one of the world’s premier sport fishing artists. In 1981, he began to climb the ranks among billfish artists with his painting School’s Out – Atlantic Blue Marlin and Flying Fish. His work is now widely collected, and his limited-edition prints sell out quickly. He has been an illustrator for Marlin magazine since 1984. His work has appeared on the covers of Marlin, South Carolina Wildlife, saltwater fishing magazines, horse racing magazines, any number of Charleston publications, and on Gamefish, a hardbound annual published in Paris. He has illustrated a reading book for adults published by Barnwell Loft Limited in New York, a special project for John because as a child, he was diagnosed as dyslexic and bears the scars of that memory and his mistreatment because of it.

“Spell cerulean,” I once said to John when we were discussing shades of blue.

“Don’t ask me that,” he laughed. ”I’m dyslexic. I read backwards.” When he saw I looked sympathetic, he said, “I didn’t consider it a dysfunction. Dyslexia is misunderstood. Consider the possibilities, especially for a painter. Take lowercase b. You can flip it over to be p, or q, or lowercase d. Dysfunction? No. It’s having more vision—the vision to see more possibilities.”

First Light, a huge 48 x 72 oil-on-canvas.

John Doyle now lives and works in a huge upstairs studio loft above retail shops on King Street in the commercial district of Charleston. He moved into the building after Hurricane Hugo destroyed his studio a few blocks away. The new studio, formerly the old Charleston Ballet theater, is unfinished, but a wonderful setting. It reveals spacious white rooms, Oriental rugs laid on finished pine floors, careful, simple Iight—a Zen-like style. John’s paintings and photography hang on the walls. One large work is an unfinished charcoal of him as a boy, painting at the easel.

I met John at his new studio in January to see what he had done, the pieces he had hung. I paused at the unfinished charcoal, a work I had seen many times before, the only old work on the walls. John “Five years from now,” he says, “I’d like to be like a kid when it comes to my painting. I’d like to be able to get up in the morning and brush my teeth while standing in front of the easel ready to paint. I want to be so excited about painting that it will not be work. A child puts out a lot of energy but he calls it play. I want painting to be play. That’s what I want. That’s when I will be doing the absolute best work I can ever do.”

blue marlin goes airborne while chasing a school of bluefish in Doyle’s Cha-Cha-Cha.

Perhaps I stayed too long at the charcoal. John started to study it, too, intently, as if he had never seen it before. After several minutes he began to talk. “The first pencil drawings I ever did were on the margin of a church program, probably out of the boredom and torture of being confined in church every Sunday. There’s an irony here, the irony being that art comes from God. I’ve since come to believe that God has little to do with the church. And a lot to do with my art.

“I had been a practicing alcoholic for 25 years and sober for seven years when father died. Sitting on the front pew at his funeral, I was suddenly faced, right then and there, with all the rage and anger I’ve ever felt. I was furious at the preacher, furious at the, church, curious at what organized religion does to the poetic soul.

“Not that I don’t believe in God; I am a very spiritual man. When I paint, I paint life-force energy. It comes from purple shadows, from trees, from the beauty of fish, from the sun and sea. They’re alive, the sun’s alive. When I paint I try to report on what I see as the beauty of God. I never found it in church.

“I walked out of my father ‘s funeral. I felt that to stay would not have been respecting my father at all. It seemed such a sham. I should’ve walked out of the church at age four. But it took me 41 years to get the strength to stand up for what I believe in. It was profound for me, the fact, the occasion.

“You see, I have this belief that you can only be true to yourself if you do what makes you happy. This certainly applies to my painting. Painting is my talent. It is my calling. I truly feel I do not have a choice. If I had a choice, painting would certainly not be a logical one. It would’ve been more logical to have been a doctor. But there are more doctors out there who were never meant to be doctors, whose fathers and grandfathers were doctors, who carry on that tradition. They may have wanted to be firemen because they went to the firehouse in elementary school and saw a fireman in red suspenders, or may have wanted to be poets, or whatever.

“In my opinion these doctors will never be happy being doctors. No amount of BMWs, no amount of trips to Bermuda will make them happy. If you have a calling to be a stripper at the Peppermint Lounge, you’d better do it, ’cause you’ll never be happy if you don’t.”

He led me away from the charcoal and over to a copy of a recent sport fishing print, a blue marlin exploding from the sea, feeding on a school of yellowfin tuna. The piece is called Cho-Cho-Cho.

“You see this?” he said, indicating the print. “You’re seeing the rage of John Doyle in church. It hit a chord with my viewers. Two hundred limited edition prints of it sold out in less than four months. At $300 a print, people must have felt something. “We were getting ready to leave the studio. John was putting on his jacket when he called over to me across the room. “So, was God in the church? Nah. He was sitting with me on the Battery wall or riding with me through those purple shadows. Or riding the waves with a blue marlin.”

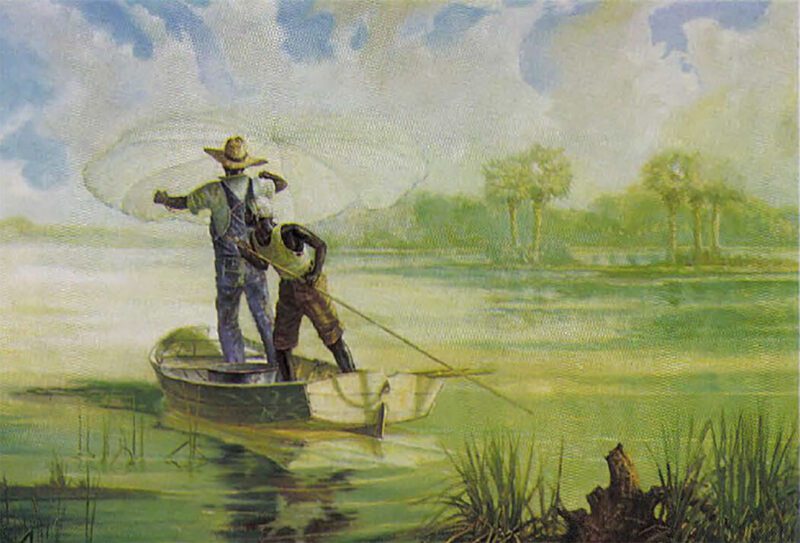

Black Shrimpers reflects Doyle:S love for painting the Carolina coastal country.

We left his studio and crossed King Street to Le Midi, a French restaurant where John frequently dines. It was one of those Charleston nights when nothing much moves; a sub-tropical, warm January. The air was still, the streets deserted. It was offseason for tourists. The restaurant was nearly empty.

John took his time deciding on a table. After a careful survey of each one, we sat down by the kitchen area and ordered grouper and escargot and dined to the strains of Edith Piaf wafting out of stereo speakers.

While we sat there, I remembered something John said to me once, when I interviewed him for another magazine years ago. It was a typical John Doyle quote. He said, “Life is like a restaurant and most people sit where they are told.” A statement that struck me as so profoundly true I’ve never forgotten it.

After dinner, we left the restaurant and said goodnight. I climbed into my car, while John crossed King Street once more and headed home.

I don’t see John so often anymore, except ambling up or down King Street where he is a familiar pedestrian sight, going here and therein a city where you can still walk just about anywhere downtown. But I was thinking, watching him cross King Street that night, how much I admire him.

I don’t see John so often anymore, except ambling up or down King Street where he is a familiar pedestrian sight, going here and therein a city where you can still walk just about anywhere downtown. But I was thinking, watching him cross King Street that night, how much I admire him.

One thing about John Doyle, he never sits where he is told. He’s always shaking up the seating arrangement.

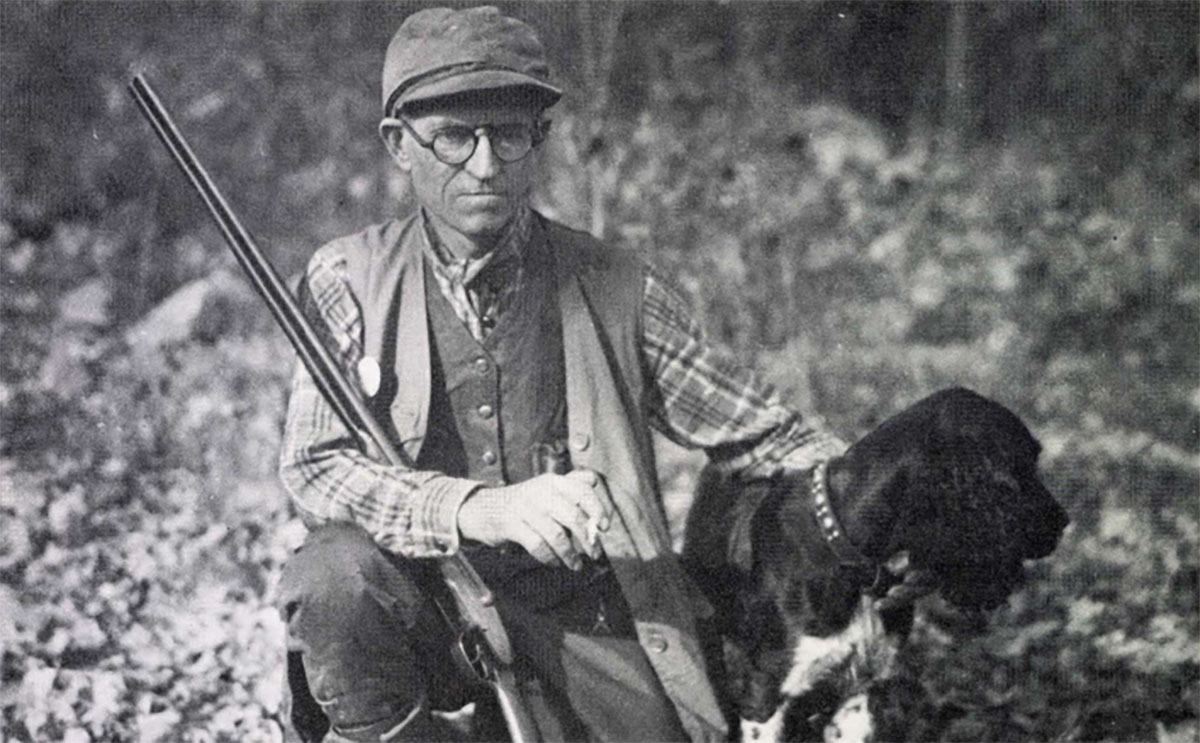

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly. Buy Now

This book is a selection of some of Grey’s best work, and the stories and excerpts reveal a man who understood that angling is more than an activity–it is a way of seeing, a way of being more fully a part of the natural world. No writer exceeds Zane Grey’s ability to integrate the fishing experience with a world he saw so vividly. Buy Now