“Sporting art” is exactly that: art with a sporting theme.

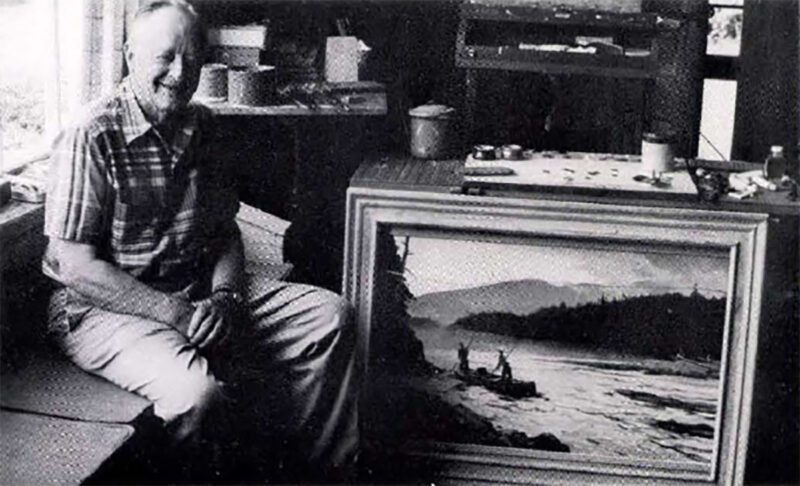

Pleissner in his Pawlet, Vermont studio in 1972 “To me,” he once said, “there’s something else besides 14th Street and the subway crush . … Watching the seasons change up here in Vermont is a little more important.”

“Most sporting art isn’t good art….” This statement, strangely enough, was made by Ogden Pleissner, a man widely known for his “sporting art,” beautiful renderings of salmon rivers, trout streams, bird covers, and duck marshes. However, despite his success with such scenes, Pleissner considered himself not a sporting artist, but rather, a “landscape painter, a painter of landscapes who also likes to hunt and fish.”Pleissner objected to most sporting art because of his belief that “a fine painting is not just the subject…It is the feeling conveyed of form, bulk, space, dimensionality, and sensitivity. The mood of the picture, that is most important. ” Many sporting artists, he asserted, fail to “capture a mood.”

During a professional career that spanned 55 years, Pleissner produced more than 2,500 large oils and watercolors and perhaps twice as many smaller paintings, all of which illustrate his ability to convey those important elements of form, bulk, space, dimensionality, and sensitivity. Art collectors will be interested to know that in addition to the great many original oils and watercolors Pleissner painted, he also supervised the production of signed, limited edition prints of more than 30 of his sporting pictures. He also produced eight lovely drypoints during the early 1940s in small editions.

Thomas S. Buechner, an old friend and an authority on art history, has this to say about Ogden Pleissner: “There is a special joy in witnessing a championship performance — in tennis, in politics, or in painting. Anyone who knows anything about recording the visual world in paint must be awestruck by Ogden Pleissner’s performance. Extremely complicated subjects are rendered so accurately, so spontaneously, so appreciatively that comparison with Homer and Sargent is inevitable ….Originality, self-expression , scale are among the principal criteria in today’s art world; observation , mood, taste are among those in the tradition to which Mr. Pleissner belongs. Catching a fish or fueling a plane may be the subject, but the picture is about an emotion that the artist has; he uses these things, arranges them, colors them, lights them to convey a mood. The mood itself is surprisingly consistent from the very beginning: reflective pleasure. There is no moral outrage, no heavy melancholy, no awesome conflict. Mr. Pleissner invites us to transcend our focus on action to see the whole scene — quietly, and from a little distance.”

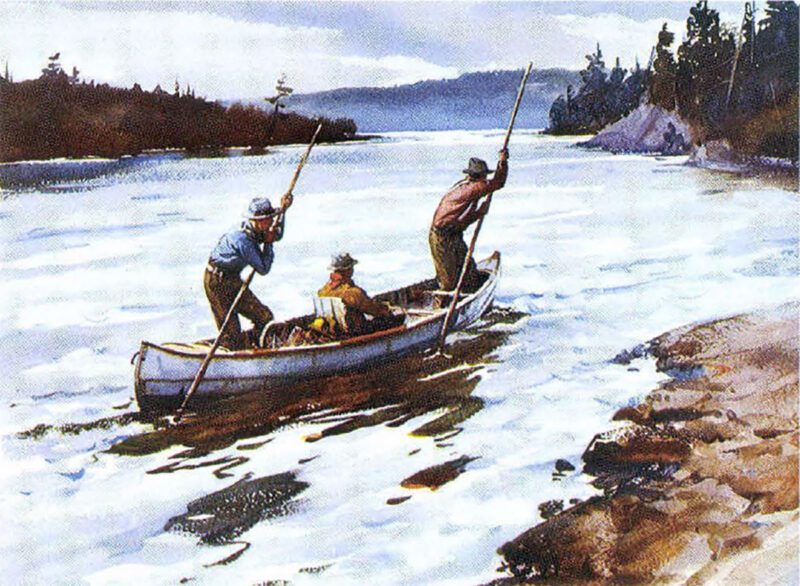

Fishing the AuSable.

Ogden Minton Pleissner was born in Brooklyn, New York, April 29, 1905, and grew up and attended school there. After a happy childhood in Brooklyn, Pleissner was introduced to the American West in Dubois, Wyoming. At the age of 16 he spent two summers with a group of 15 or 20 other boys, packing all the way through Yellowstone Park and sometimes being gone for two months at a stretch. Pleissner spent a third summer on a dude ranch and did plenty of drawing and sketching there. His early experiences in the West later influenced his career and led to his lifelong interest in hunting, fishing, and the outdoors.

Although he had some instruction in art while at Brooklyn Friends School, Pleissner, the youngster, was largely self-taught. After graduating from high school, he attended the Art Students League in New York City for four years. His parents wanted him to go to Williams College, but since his real ambition had always been to be a painter, his wishes prevailed.

Pleissner drew constantly as he was growing up. “When I was about five years old ,” he recalled, “Mother had just had the stairway redecorated or repapered with scenic wallpaper that had gondolas and boats and things like that on it. Everything you like.This work had just been done and my mother went out one day. I got hold of a crayon and put people in all the boats going up the stairs. I got a terrific licking for my efforts. That was probably myfirst venture into the world of fine art.”

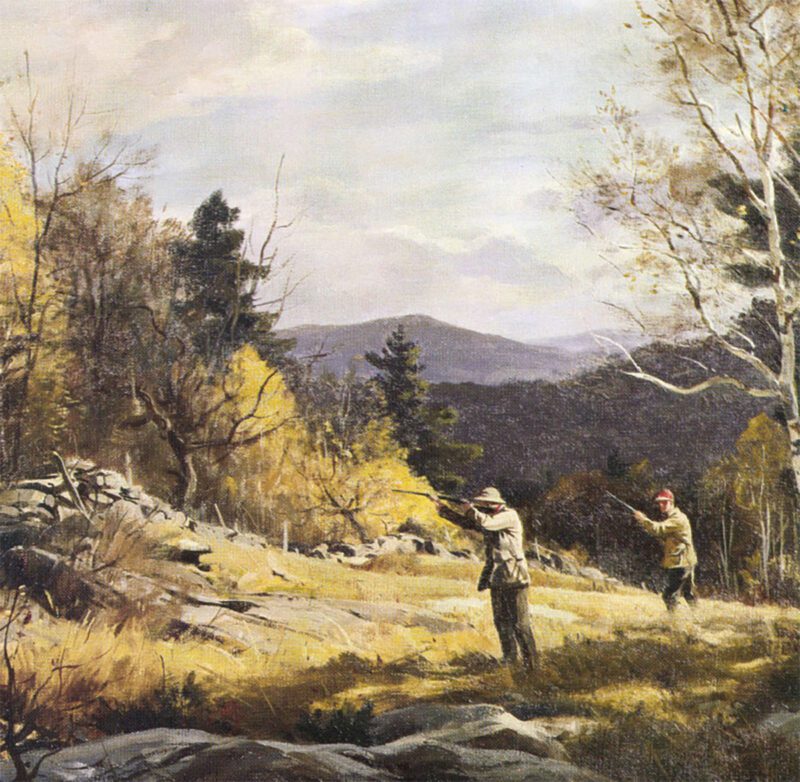

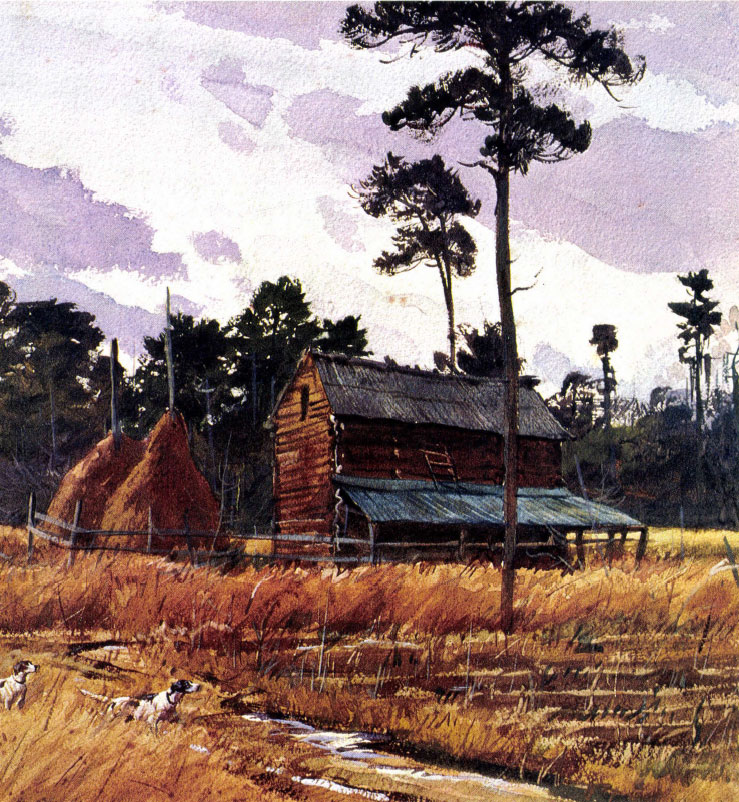

Grouse Shooting which reflects Pleissner’s preference of fall “when everything isn’t all the same color green.”

At the Art Students League, Pleissner studied for a while with George Bridgman whose textbooks on figure drawing are still the standard work in many art schools today. He then entered a class taught by Frank DuMond, an accomplished artist and a member of the National Academy, who was, in Pleissner’s words, “a great salmon fisherman, ” and he studied with DuMond for several years in New York and during the summers at a class DuMond ran in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.

The Margaree River was nearby, and it offered Pleissner firsthand experience with Atlantic salmon fishing. Pleissner commented, “I think DuMond ran the summer camp in Cape Breton because he liked to fish so much, and he seemed glad to have my company on the river.” It was here that Pleissner met his first wife, Mary Harrison Corbett of Portland, Oregon; and they were married on October 12, 1929.

After finishing his training at the Art Students League and now having a wife to support, Pleissner realized that he would have to go to work and earn some money. Capitalizing on his western experiences, he eventually took one of his pictures to Harlow MacDonald who had a fine gallery on Fifth Avenue. MacDonald agreed to put the picture in the window, and the next day it was sold. Encouraged, Pleissner took him several other pictures which also sold.

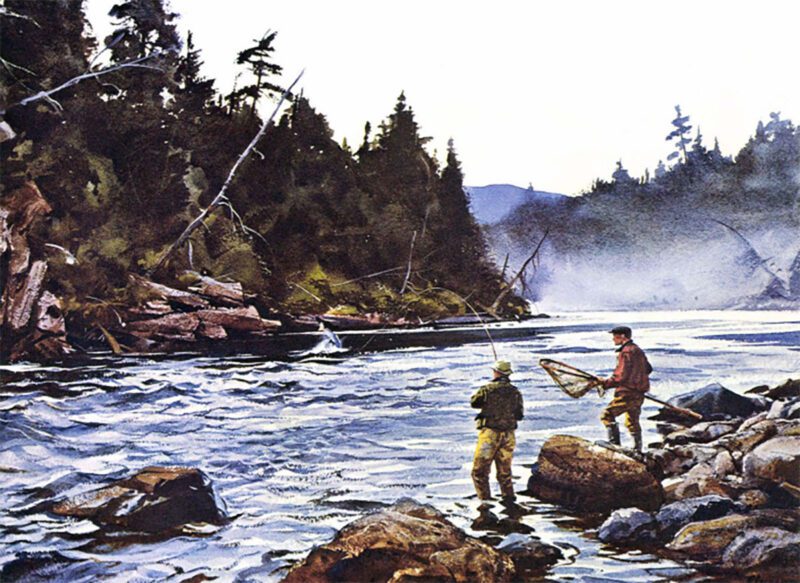

The Head of the Pool

Almost every summer for 17 years the Pleissners moved to Dubois, Wyoming, and stayed at the C-M Ranch which was run by Charlie Moore. They stayed there June through September, and while Mary helped out at the ranch, Ogden did some guiding and took the dudes fishing when he wasn’t painting. Over the years he was to paint a great many more fishing scenes. “There were a lot of people who had salmon rivers and fishing camps who liked my work and who would ask me to come up and paint something on their river. I think a great many of these people would ask me to come back again because I knew one end of a salmon rod from the other and I wasn’t a dummy at fly fishing.”

Earning a living as an artist in the Depression was a struggle for Pleissner. “One of the things that kept me going was a job teaching drawing and painting in Brooklyn. My teaching job helped a great deal and kept the wolf from the door. I sold pictures for $50-$100 in those days. There were times when the bank account was pretty much right down to nothing.”

During the early 1930s, Pleissner worked almost exclusively inoils, producing hundreds of finished paintings of western landscapes and scenes of the Maritimes and New England. “At first,” Pleissner recalled, “I was influenced a great deal by my teacher, Frank DuMond, but then a real change occurred in mywork just before the war came along. It became broader, massive, and had a great deal more depth. It was about this time that I started doing watercolors.”

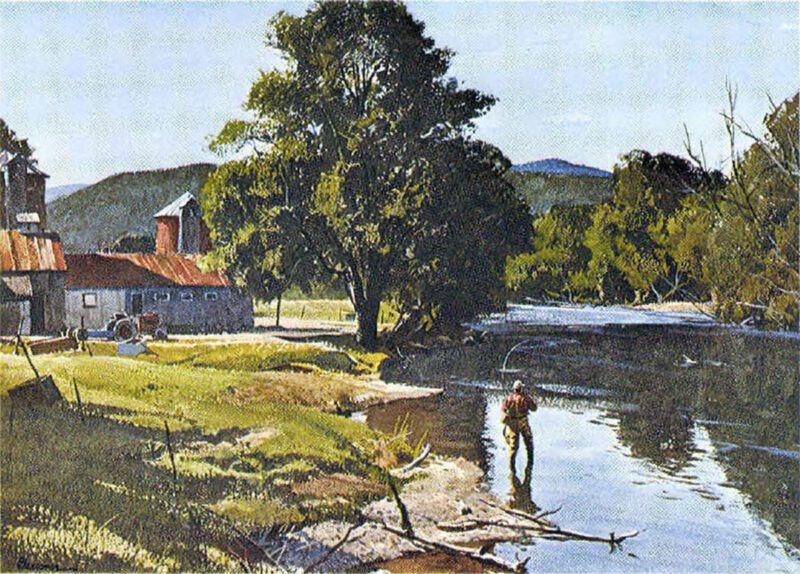

Battenkill at Benedicts Crossing

Wars have had a profound effect on people’s lives and their careers, and Pleissner was no exception. For centuries political and military leaders have commissioned leading artists of the day to depict major conflicts and military life, and frequently these artists would find themselves in the thick of battle feverishly making sketches as the fighting swirled around them. Later, these quick impressions would serve as reference so that the scene could be recreated in finished paintings. These sketches and pictures now form an important part of recorded history and represent a portion of the life work of many great artists including Delacroix, Goya, Picasso, Winslow Homer and Frederic Remington.

During World War II many fine artists were stationed with the fighting men in the European and Pacific theaters of the war. Among them were the Americans Howard Brodie, Olin Dows, Joseph Hirsch, Tom Lea, Fletcher Martin, Paul Sample and Ogden Pleissner. Their work carefully and accurately records the grim science of waging modern warfare and the aftermath of battle in a way no camera could.

Pleissner’s involvement in World War II began when he was 37, late in 1942, as an Arm y artist. Well-known by this time as a painter of western landscapes and once again looking for work, he was intrigued by the war effort. Life magazine was interested in having him work for them, and a trip was proposed to the then secret Alcan highway project to sketch and paint the construction that was underway. While waiting for his security clearance to be processed, Pleissner received a telegram from United States Army Air Force General Henry “Hap” Arnold, who knew the artist’s work, asking him if he would accept a commission in the Army Air Force as a war artist. General Arnold planned to establish an Air Force museum after the war and thought Pleissner would be the right artist to portray the use of aircraft in war for eventual inclusion in the museum.

Downs Gulch

Pleissner was commissioned a captain in 1942 and completed officer training school in Miami. After a short stay in Washington D. C., Pleissner was assigned to the Aleutians.

Until this time Pleissner had painted relatively few watercolors. However, the cold, wet weather in the Aleutians necessitated working fast and in a medium that would dry quickly by the heat of a tent stove; watercolors were a logical choice, albeit a challenging one.

It wasn’t that Pleissner didn’t appreciate the medium. “I always liked watercolors and admired those beautiful ones by Winslow Homer and Sargent. A friend of mine in New York asked me why I didn’t paint watercolors. I said I didn’t know how, and he said all you have to do is keep your board a little slanted so when you wash the color onto the paper it runs downhill. That was my only lesson in watercolor painting.”

The Blue Boat on the St. Anne

After only three months in the Aleutians, Congress, bowing to pressure, voted against further appropriations for military art, and Pleissner found himself temporarily out of work. Fortunately, Pleissner’s colonel was an old West Pointer who knew all the angles. At the time there was a directive that permitted persons who had special talent more beneficial to the war effort in a civilian capacity to be assigned to inactive duty. The colonel advised Pleissner to get on the first plane back to Washington before he was reclassified and stuck in the Aleutians as a photographer or in some other capacity for the duration of the war.

Once back in Washington, Pleissner placed a call to Dan Longwell at Life magazine asking if they still wanted him to work for them. Getting a positive response, it was arranged that he would remain with the Army Air Force doing the same sort of work but this time as a war correspondent employed by Life.

In 1943, Life sent Pleissner to England. He was stationed with the 8th and 9th Air Forces and during a two-year period traveled throughout England, France, Belgium, Germany, and Italy. While traveling, he observed many landscapes that reminded him of Wyoming and New England and others unlike anything he had ever seen. Because the battles across Europe followed strange, uncertain paths, there were many farms and villages untouched by the war sitting timelessly alongside the ugly battlefields. Such settings reinforced Pleissner’s belief that “…in a painting, a landscape… it’s the mood conveyed that counts. Constable, Homer and Inness convey a sense of place in their pictures yet there is something else that goes far beyond that.”

Mill in the Algarve (1972) (detail)

Pleissner’s experiences in the Aleutians and his travels in Europe during and just after the war had a profound and lasting effect on his work. “I saw so many things over there, when I was in France especially, that were not particularly hit by the war, and I thought that they would make wonderful subjects to come back to and paint one day.” Life’s entire collection of World War II art, comprising hundreds of paintings by dozens of artists, was given to the Army Art Department of the Department of Defense some years ago. The collection includes more than 80 of Pleissner’s paintings and most of them can be found hanging in the corridors and in the offices of the Pentagon, at West Point, and at the Air Force Academy.

The war had a very positive effect on Pleissner’s work. The need to capture a scene very quickly under war conditions (and the many hundreds of quick sketches he made as a consequence), honed Pleissner’s skill as an artist and helped him master the techniques of painting both with watercolors and oils.

After the war, Pleissner returned to Europe with Mary almost once a year for more than 30 years to paint and to enjoy hunting and fishing in England and Scotland. “I worked pretty hard in those days and did a great many sketches from which I painted. I worked seven days a week for a great many years. In art, when you get interested in what you are doing there is nothing else.”

After the Rain, Venice (1967)

The Pleissners had no children, and Mary Pleissner died suddenly in New York on March 2, 1974. Pleissner was very depressed for several years and did little painting. Eventually, however, a long friendship with a widow turned into a romance, and the artist married Marion Williams Gould on March 7, 1977. Soon after the wedding Pleissner said, “Speaking of wives, I feel that I have been a most fortunate man. My first wife, Mary, was with me for over 40 years until suddenly and unexpectedly she died of a severe heart attack. She was so loyal and always interested in what I was trying to accomplish , and I must say worked like a dog to keep everything in order and going. I’ve been told that I am a very difficult person to get along with, but she always seemed to put up with me. Now again I have married another lovely woman, Marion , and my fortune is still holding. She is a great help to me and is an excellent critic of my work.”

Most people know Pleissner as a painter of sporting art; but just what is “sporting art”? Certainly it is not the pictures one typically finds on the front of sporting catalogs or the majority of the covers of hunting and fishing magazines. These are illustrations commissioned by businessmen to promote a product: long underwear, fly-dope, and shotguns among others. Nor is it most of the thousands of so-called “sporting art prints” that flood the market each year in huge editions. Some of these painters are great photographers, and every feather on the duck is there, every scale of the fish. The subject appears frozen in time, motionless, photographic. Nothing is left to the imagination; there is nothing for the mind’s eye to see. But is it art or is it illustration?

“Sporting art” is exactly that: art with a sporting theme. There is obvious or hidden prey in the picture. Game is depicted in a well-painted landscape that may also include a figure holding a rod or gun, or it simply could be a painting of a stream or hillside where one just knows a trout or partridge lies waiting.

Thunderbolts (1944)

Great artists who have the potential to create sporting art know the habits of wild creatures and have committed to memory every detail of their habitats. These are men who have experienced the thrill of Atlantic salmon or large trout taking a well-presented fly, the explosion of a bursting covey of quail, sunrise on a duck marsh, running the rapids in a canoe, or sleeping under the stars. Few have produced great sporting art. It is in a class by itself and has had very few masters, among them Winslow Homer, Frederic Remington, Carl Rungius, Frank W. Benson, A.B. Frost, A.L. Ripley, Thomas Eakins, and Ogden Pleissner.

Pleissner’s sporting pictures are beautiful landscape paintings that always catch and hold the eye. After viewing hundreds of examples of Peissner’s work, I frequently find myself wondering: is this a sporting picture or a landscape painting? This is the secret of great sporting art: to depict the sporting scene and to capture the essence of being outdoors.

Northeast Salt Pond, Nantucket

Referring to his love of the outdoors, Pleissner once said, “The philosophic aspect of life never interested me very much. I just live it. Fishing, for example: I’ve always loved to fish. Why? I don’t know. I was born in Brooklyn, but when we went away I always used to fish if I had the opportunity, and that was one of the reasons I went out west. I wanted to get outdoors, fish, and go on pack trips. ” He was not alone. “A large number of the fishing and shooting fraternity are awfully nice people who love to travel and enjoy the outdoors. They are conservationists and like to be out and see the game and the country. They’re damn fine people, I have found, and they and bird dogs make very good friends.”

Ogden Pleissner died suddenly and unexpectedly at the age of 78in London on October 24, 1983. He was a great artist, a man of keen perception, deep sensitivity, charm, warmth, and humor. Ogden’s oldest friend, Sam Webb, remembers him as “a tireless worker and his own harshest critic. He was one of the most modest men I have ever known, and he had a keen sense of humor.”

Edge of the Cottonfield, Quail Shooting

Ogden’s friend, Donal C. O’Brien, recalls that he was “the person he wanted to be. He was a natural. He was also an extraordinary blend of things that in most people might seem inconsistent, but in Ogden were balanced and right. Ogden had great style; he was learned, sophisticated, even elegant, but he could cuss like a trooper and tell the saltiest stories in camp. He was gentle, sometimes shy, but he had a sharp wit and temper that would come on like a line storm and be over just as quickly. Ogden was equally at home in the club rooms of the Century Association in New York and in Sam Webb’s Three Islands Camp on the Grand Cascapedia. He could move from a driven grouse butt in Scotland to the ruffed grouse covers of Yermont without breaking stride. He was a man’s man and a ladies’ man. Whatever he did, he did easily, with grace and style and dignity and in the most modest and natural manner. ” All these qualities are evident in his work.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared in the 1984 Sept./Oct. issue of Sporting Classics.

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now

The Sporting Life is a celebration of gundogs and horses, hunting and fishing as expressed through the rich and exuberant paintings of Joseph Sulkowski. Buy Now