Here’s the portfolio; look what’s inside.

People are known for doing the one thing at which they are best. That’s what we were telling the artist one afternoon in his studio with the window as big as The Ritz. There are well-known western artists and wildlife artists and landscape artists and seascape artists and sporting artists, but rarely is the practitioner who excels in one field caught dabbling, much less excelling, in any of the others. The practitioner at the oversized window fixed us with a certain look of unrepentant guilt. “I probably shouldn’t be saying this,” he allowed, “but I’d get awfully tired doing only one thing. I need diversity. I love the diversity of what I do.”

People are known for doing the one thing at which they are best. That’s what we were telling the artist one afternoon in his studio with the window as big as The Ritz. There are well-known western artists and wildlife artists and landscape artists and seascape artists and sporting artists, but rarely is the practitioner who excels in one field caught dabbling, much less excelling, in any of the others. The practitioner at the oversized window fixed us with a certain look of unrepentant guilt. “I probably shouldn’t be saying this,” he allowed, “but I’d get awfully tired doing only one thing. I need diversity. I love the diversity of what I do.”

What Arthur Shilstone does, he does very well indeed — watercolors, mostly, some collage — but what a diversity of subjects, what a high-wide-and-handsome choice of fields, what a roving but resourceful eye to see and interpret so many challenging aspects of our challenging world.

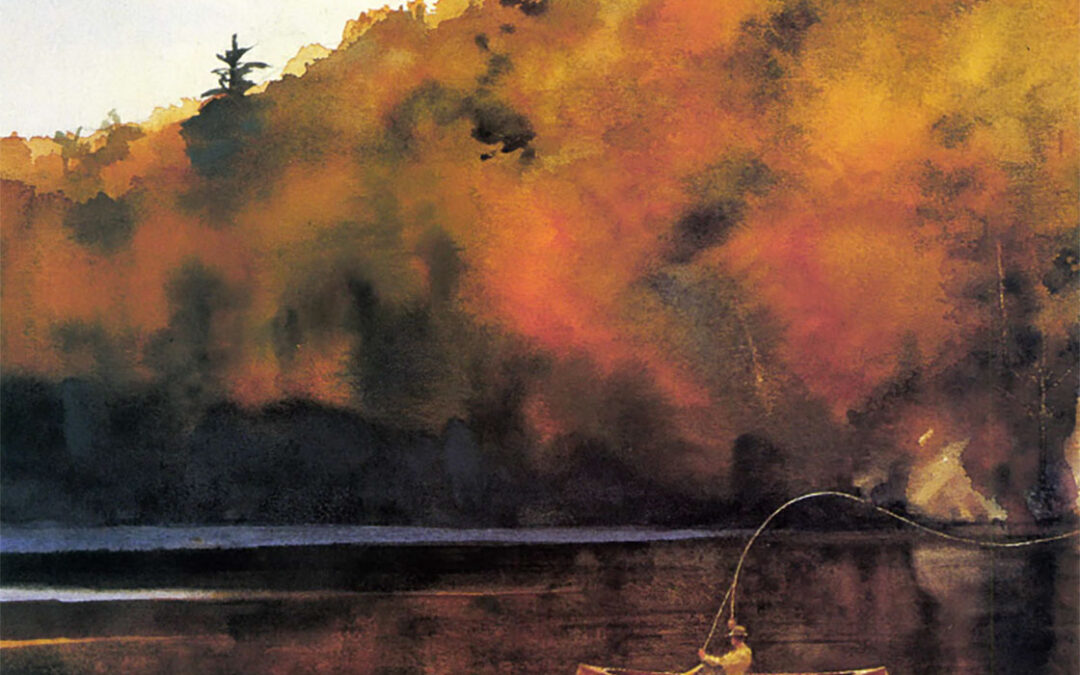

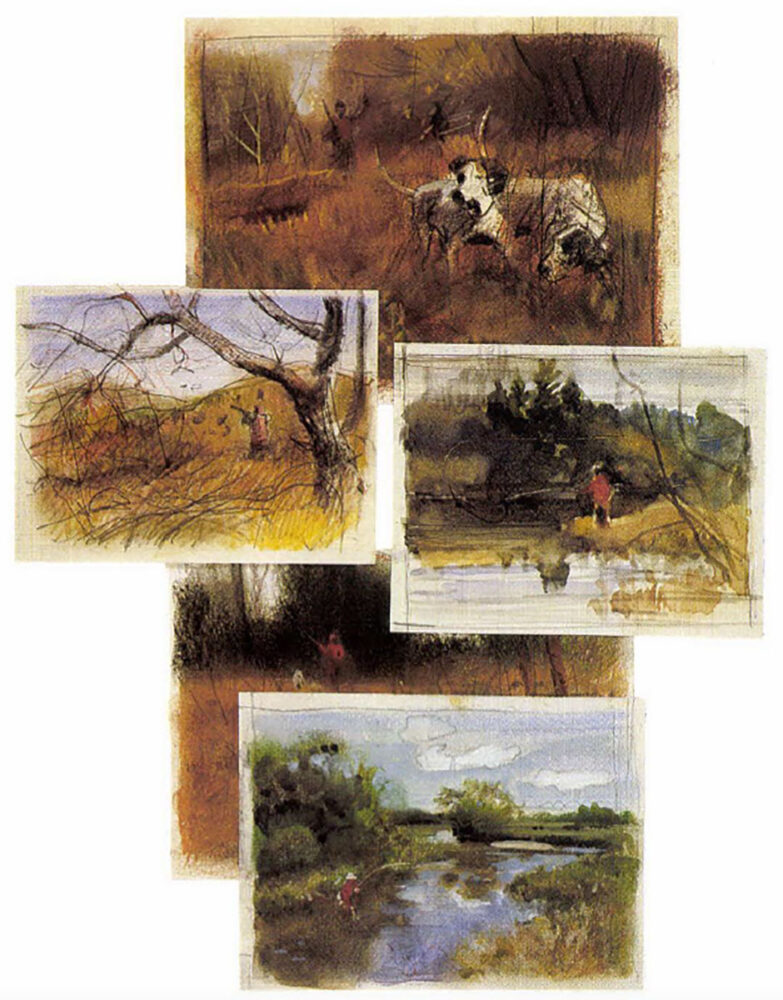

Here’s the portfolio; look what’s inside. American history, over-the-hill and in the making. Explorations and discoveries. Men at war. The raw edge of heavy industry. Countdown to blastoff, Cape Canaveral. Courtroom confrontations. Kitchen herbs. Jazz musicians. Street scenes. Tropical storms. And here, the hunt. The guide boat. The tight line. The evergreen ridge. The great outdoors. At last, the stuff that figures at the front and center of all of Arthur Shilstone’s multitudinous diversities.

It was not always this easy to locate the artist’s pivotal turf, his favored milieu, possibly because, until recently, he would not allow himself to have one. He was too busy being an illustrator — a “painterly illustrator,” as one critic accurately described him a number of years ago. For a long time, it seemed, there were deadlined demands from magazines, advertising agencies, book publishers, record companies. Beneath the great window of his studio, he sat at the drawing board, making lines and washes on assignment.

It was not always this easy to locate the artist’s pivotal turf, his favored milieu, possibly because, until recently, he would not allow himself to have one. He was too busy being an illustrator — a “painterly illustrator,” as one critic accurately described him a number of years ago. For a long time, it seemed, there were deadlined demands from magazines, advertising agencies, book publishers, record companies. Beneath the great window of his studio, he sat at the drawing board, making lines and washes on assignment.

To be sure, it wasn’t always all work and no play. Beyond the window, back in those New England woods, there were grouse to be flushed and farther afield, rivers to wade and a summertime beach at Block Island, the artist-as-beachnik casting for stripers and blues.

Arthur had come to these outdoor pursuits at an early age, in the cusp of his formative years and later had squirreled away time for them whenever and wherever he could. But it was always to play, never to work, never in any serious or extended way to make the woods and hills and rivers and ponds help buy groceries as line and wash on a piece of paper. And then, maybe 12 years ago, something happened.

“You decided,” we said, “that it was time for a change.” He denied it, saying it was circumstance. “A few years back, things got slow. When you’re an illustrator and you’re not terribly busy, there are only about three things you can do with your time. You can take your portfolio and hit the pavement and try to get a job. You can sit at your board and make new samples to put in the portfolio to get you a job. Or, you can do something for yourself, something of your own that is strictly for you. So when things slowed down, I started doing some work for myself. The sporting scenes, as paintings. I had never done that before. And I was delighted to find I could sell them.”

“You decided,” we said, “that it was time for a change.” He denied it, saying it was circumstance. “A few years back, things got slow. When you’re an illustrator and you’re not terribly busy, there are only about three things you can do with your time. You can take your portfolio and hit the pavement and try to get a job. You can sit at your board and make new samples to put in the portfolio to get you a job. Or, you can do something for yourself, something of your own that is strictly for you. So when things slowed down, I started doing some work for myself. The sporting scenes, as paintings. I had never done that before. And I was delighted to find I could sell them.”

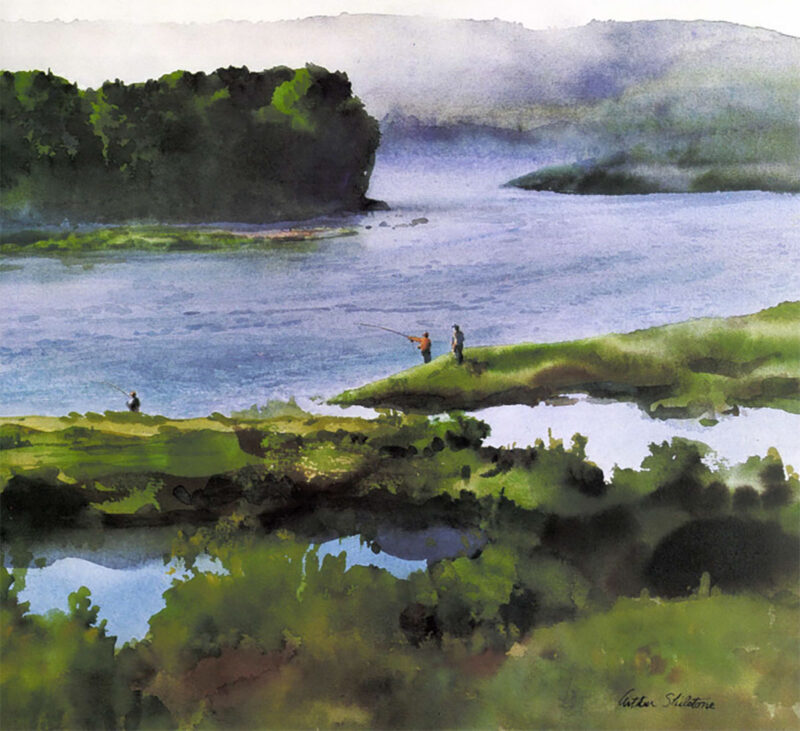

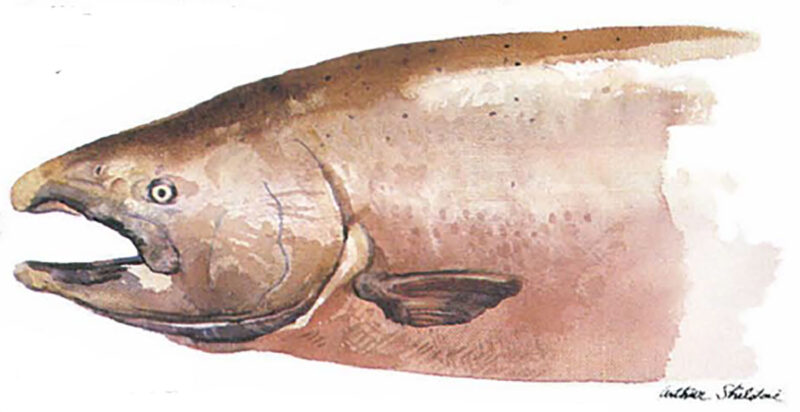

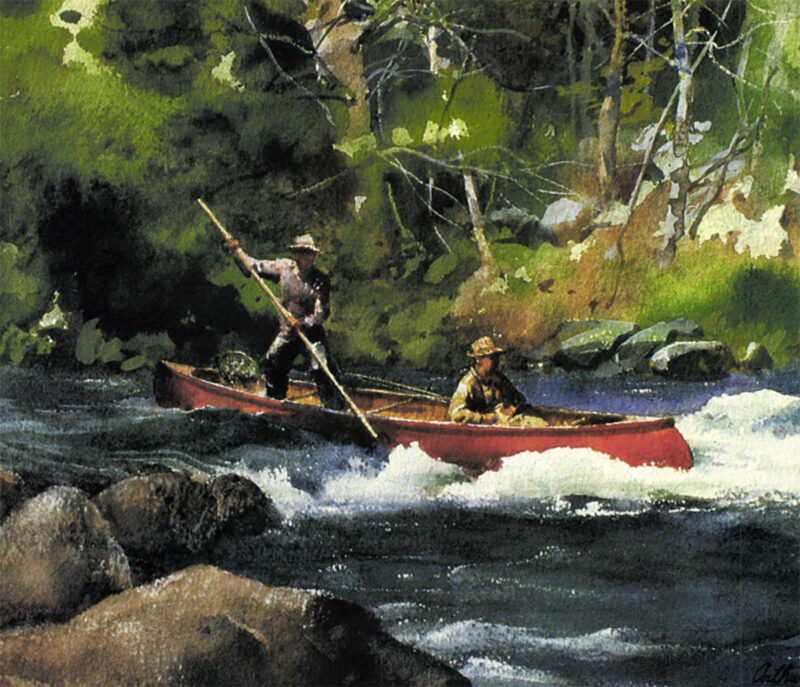

Nowadays, Shilstone’s outdoor scenes — of salmon beats on the Miramachi, Adirondack lake country, Chesapeake marshes, Alaskan tundra, Connecticut tarns — are selling as paintings or prints at shows and galleries throughout America.

In my own home, hanging beside my word machine, is a Shilstone print, the gift of a very good friend. To the flat white basement wall it brings the cool green texture of an Adirondack afternoon, the shadows deepening upon the surface of the inlet, the paddler holding steady, the dude in the bow hooked to what appears to be, from the curvature of the fly rod, one helluva fine fish. I could swear I have been to this place, but by Shilstone’s account of the exact location, I confess I’m mistaken. It is all a trick of the hand and the eye. His hand, to be sure, but my eye. Yes, there is a sense of place here, of a certain kind. But it is not the geographer’s place, not a thing one can hang out to dry on the coordinates of physical detail. Under Shilstone’s hand, details are blurred in the wash, and what emerges is as much a feeling as a picture; as much a sense to be placed, if you will, as a place to be sensed.

We are informed that his own first place, that is to say his parents’, was a large house in suburban Essex County, New Jersey, and that the year was 1922. The boy’s father wore a business suit and went each weekday morning to New York. Young Arthur was seven when the Crash came to Wall Street, a bit older when the effects of the Great Depression finally caught up with his dad. They lost the big house and moved to a winterized summer cottage on Lake Mahopac in New York State. “It was a disaster for the family,” the artist was saying, “but just about the best thing that ever happened to me. Our new place was right on the lake. And that’s where my interest in hunting and fishing began.”

“And what did you think you’d be doing when you grew up?”

“I don’t know. I never thought I’d be an artist. I suppose I thought I’d do what one’s supposed to do — be a businessman, wear a suit and tie, go into New York City and sit some day in a corner office.”

“I don’t know. I never thought I’d be an artist. I suppose I thought I’d do what one’s supposed to do — be a businessman, wear a suit and tie, go into New York City and sit some day in a corner office.”

“So how did you come by the drawing board.”

“I did some drawing in high school. There was an art teacher who encouraged me to consider art as a career. My reaction was probably What? And live in a garret? I thought that’s what all artists did. But the teacher explained that there was something called illustration and commercial art, and that if you were good enough, you wouldn’t have to settle for a garret.” After high school graduation, he enrolled at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York. And then something happened, something called World War II.

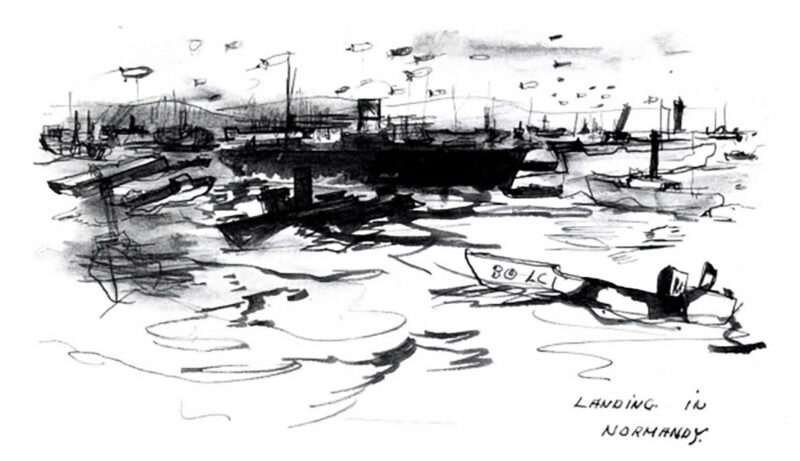

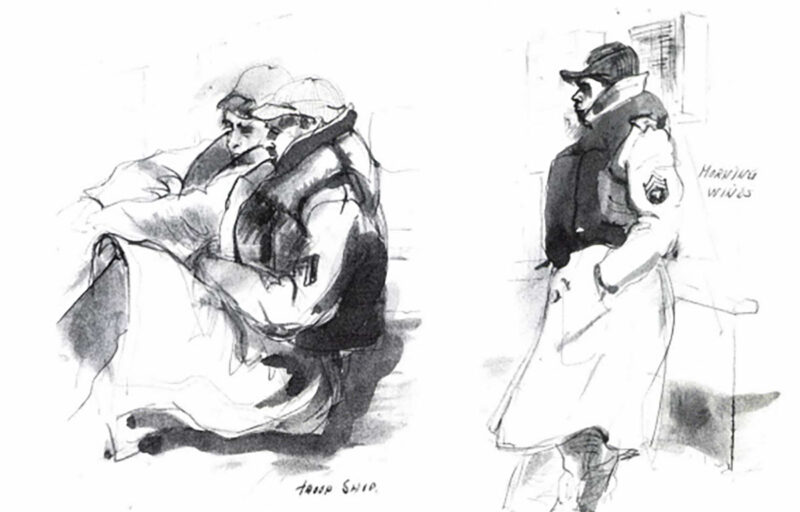

Shilstone enlisted, got assigned by and by to the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion at Ft. Meade, Maryland. The outfit specialized in creating deceptions and special effects. Such men as this painterly illustrator-to-be and Arthur Singer, soon to carve out his niche as a topflight painter of birdlife — here they were in GI mufti, learning how to deploy entire regiments of inflatable rubber93-pound M-4 tanks. They shipped out to England. Shilstone had his sketchbook and a fountain pen. The ink was made to wash under his wet thumb. His buddies were his best subjects. They hit the beach two weeks after D-Day. Going in, Shilstone saw the whole wide sweep of Ike’s Armada, the warships holding steady in the Channel, the barrage balloons floating above the Normandy beachhead. He would never forget it, in part because his sketchbook would never let him.

At the end of the second war to end all wars — could there possibly ever be another? — Shilstone returned to Pratt, finished his studies, and hit the sticky sidewalks of commercial art at a full run. He could afford to run, his portfolio being so light. Book jackets, album covers, direct-mail catalogs and annual reports barely kept him from the dreaded garret. But once again something happened. Arthur Shilstone, in the knee-pants of his career, got discovered by LIFE magazine, at the apex of its prime. The relationship lasted for 10 years, through scores of assignments: the lurid Sam Shepard murder trial, the Senate funeral of Joseph McCarthy, school integration argued before the Supreme Court, investigations into the sinking of the ocean liner Andrea Doria. The LIFE exposure led to other assignments: an extended Latin America gig (for Varig Airlines), six weeks’ coverage of the Korean War, as viewed through the operations of an air-lift service, including evacuation of wounded soldiers from harm’s way; and for NASA, a series of paintings of the space shuttle, including its maiden voyage.

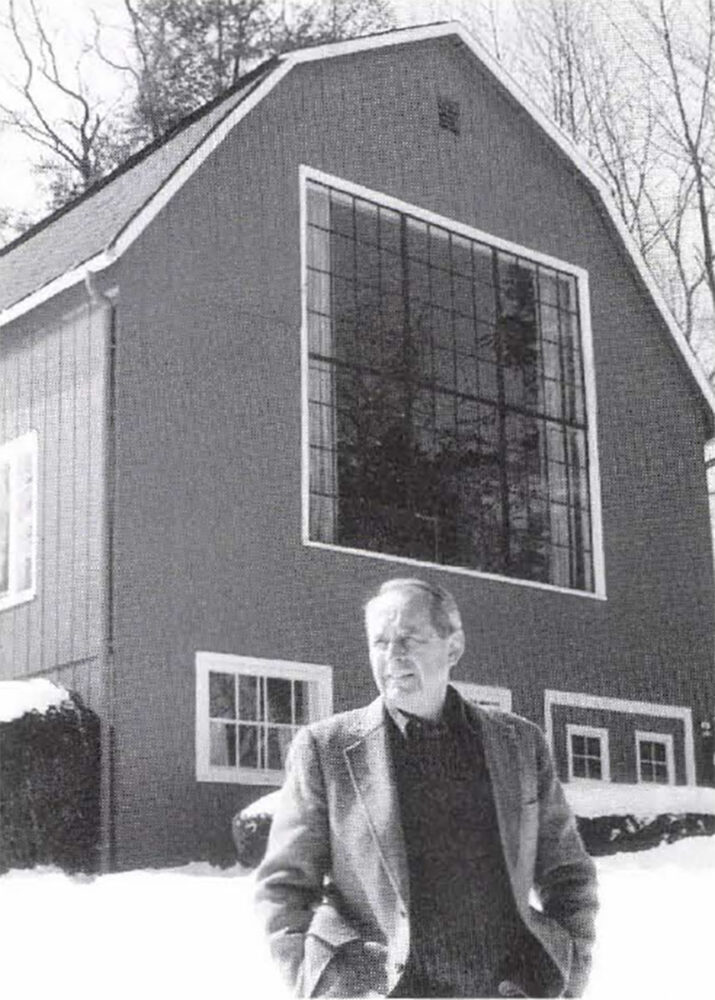

Meanwhile, Shilstone and his wife, Beatrice, a fashion editor for Women s Wear Daily and later a stylist, were putting distance between themselves and the mythic land of the garrets of Uppercase Art. One of their first stops was Westport, Connecticut; and then on to Redding, this woodsier burg just a few miles north up the Saugatuck River Valley. Redding likewise felt comfortable with creative types (in fact, the feeling was and is mutual). It had already embraced, however briefly, at least one famous word slinger-in-residence (Mark Twain), esteemed photographer (Edward Steichen) and world-class music man (Charles Ives). So now it was ready for a good solid painterly illustrator, or illustratorly painter, whichever came sooner. The Shilstones spied this converted barn on the west side of town, checked out its north-facing studio window (225-square-feet of glass panes), its 25-footceiling, its fireplace and settled in. The woods out back were strumming with grouse. There were trout in the Saugatuck.

Meanwhile, Shilstone and his wife, Beatrice, a fashion editor for Women s Wear Daily and later a stylist, were putting distance between themselves and the mythic land of the garrets of Uppercase Art. One of their first stops was Westport, Connecticut; and then on to Redding, this woodsier burg just a few miles north up the Saugatuck River Valley. Redding likewise felt comfortable with creative types (in fact, the feeling was and is mutual). It had already embraced, however briefly, at least one famous word slinger-in-residence (Mark Twain), esteemed photographer (Edward Steichen) and world-class music man (Charles Ives). So now it was ready for a good solid painterly illustrator, or illustratorly painter, whichever came sooner. The Shilstones spied this converted barn on the west side of town, checked out its north-facing studio window (225-square-feet of glass panes), its 25-footceiling, its fireplace and settled in. The woods out back were strumming with grouse. There were trout in the Saugatuck.

And there was trouble on the horizon. A lot of other people were moving into Redding and similar places during this post-war period, and some of them were not being creative at all about how they developed the land and chopped up the hills with their homesites.

Before you could say enough is enough, Shilstone was throwing in his lot with a handful of other likeminded environmentalists, all founding fathers and mothers of the Redding Land Trust, an organization conceived in high dudgeon over what developers were doing to their town and dedicated to the Thoreauvian proposition that in wildness is the preservation of ruffed grouse and speckled trout. Today, thanks in part to the early efforts of Shilstone and friends, Redding, Connecticut, now has nearly 600 acres of open space and is regarded as a national showcase of land saving, a town that wrote the book on how to weave Nature into the daily fabric of people’s lives.

Because of Shilstone’s abiding concern for nature and love of the outdoors, some of the artist’s Redding neighbors assume these subjects are his only ones. They are surprised to learn, if they bother to ask, that his work has appeared in more than 30 magazines, ranging the alphabet from American Heritage to Yankee, running the gamut from Smithsonian and Sports Illustrated to Gourmet and Military History Quarterly. Permanent collections also reflect the artist’s versatility. There are Shilstone pieces on exhibit at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration Museum at Cape Canaveral, the National Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown and the Museum of American Illustration in New York City, among others. Mill Pond Press of Venice, Florida, publishes limited editions of his sporting prints; and in the Big Apple, sporting originals hang in the galleries of J.N. Bartfield and Sportsman’s Edge.

Shilstone’s admirers are unstinting in their praise. Fred King of Sportsman’s Edge says: “Watercolor is not an easy medium but Arthur makes it seem as if it were. His proportions are so good. He positions his figures at a distance and fits them into the landscape. There is a wonderful softness in his work.” Jon Apgar of the Bartfield Gallery calls Shilstone “one of the foremost watercolorists in America.” And Smithsonian Picture Editor Caroline Despard, who has worked with Shilstone on a number of historical stories, says: “The remarkable thing is that he can do historically accurate work and still achieve freshness and spontaneity. He is such an evocative master of watercolor, there are very few who come anywhere near him.” At the risk of slighting other artists with whom she often works, Despard confesses that the only pictures on the walls of her office are Arthur Shilstone’s.

Shilstone’s admirers are unstinting in their praise. Fred King of Sportsman’s Edge says: “Watercolor is not an easy medium but Arthur makes it seem as if it were. His proportions are so good. He positions his figures at a distance and fits them into the landscape. There is a wonderful softness in his work.” Jon Apgar of the Bartfield Gallery calls Shilstone “one of the foremost watercolorists in America.” And Smithsonian Picture Editor Caroline Despard, who has worked with Shilstone on a number of historical stories, says: “The remarkable thing is that he can do historically accurate work and still achieve freshness and spontaneity. He is such an evocative master of watercolor, there are very few who come anywhere near him.” At the risk of slighting other artists with whom she often works, Despard confesses that the only pictures on the walls of her office are Arthur Shilstone’s.

So, we were telling the favored artist at the end of one fine afternoon: With so much demand for his work nowadays, he probably could never find time to get out in the great outdoors.

So, we were telling the favored artist at the end of one fine afternoon: With so much demand for his work nowadays, he probably could never find time to get out in the great outdoors.

Silhouetted in the natural light of the studio window, Shilstone nodded his head, No. He did get out now and then with his working materials. But not with a shotgun.

“Why not?”

“Haven’t you noticed, the hills keep getting steeper.”

“So?”

“Steeper hills,” he said, “heavier shotgun.”

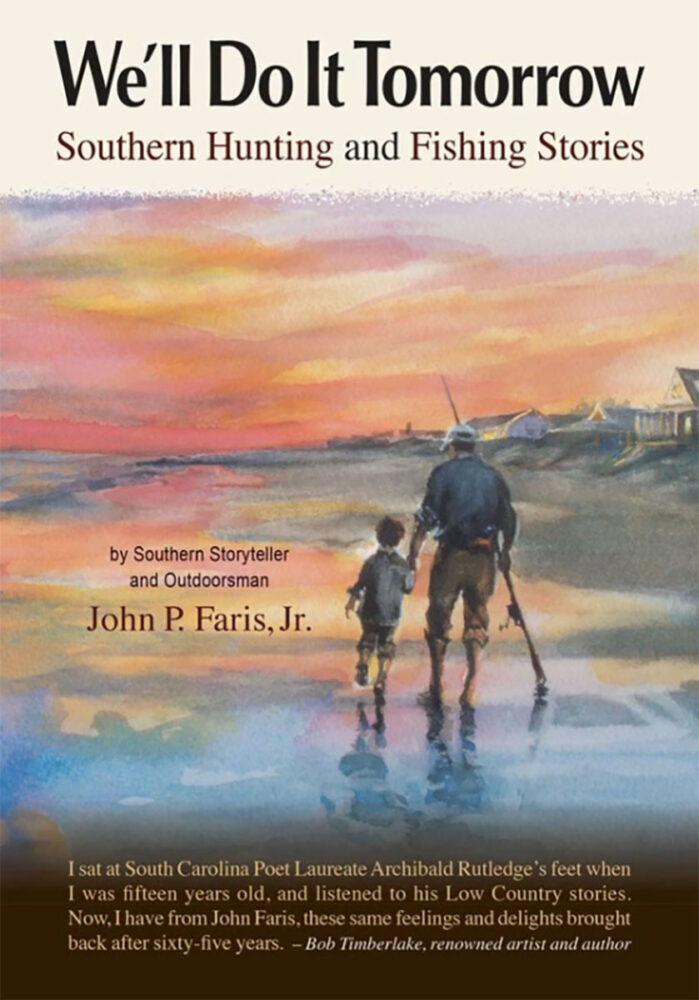

In this collection of stories, John takes us along the creeks and rivers of his native Laurens Country, South Carolina to shoot mallards and wood ducks. He also tells of unusual yet successful methods of taking white-tailed bucks on his farm in Union County, South Carolina. We’ll Do It Tomorrow is more than a book of tales about hunting and fishing, these stories are about the joys and sorrows of life. They will linger in your heart and leave you wishing for more. Filled with 15 stories and 30 illustrations We’ll Do It Tomorrow is definitely a keeper. Buy Now

In this collection of stories, John takes us along the creeks and rivers of his native Laurens Country, South Carolina to shoot mallards and wood ducks. He also tells of unusual yet successful methods of taking white-tailed bucks on his farm in Union County, South Carolina. We’ll Do It Tomorrow is more than a book of tales about hunting and fishing, these stories are about the joys and sorrows of life. They will linger in your heart and leave you wishing for more. Filled with 15 stories and 30 illustrations We’ll Do It Tomorrow is definitely a keeper. Buy Now