Cuba offers a party atmosphere: sunshine, sparkling seas and miles of white sand. It also offers some of the best cocktails and cigars on Earth. But as anyone knows who visits here, when it comes to attractions, its people are its greatest stock in trade. Cubans are super-sensitive, polite and warm-hearted. They are well-educated in world affairs, yet remain steeped in the old Latin American traditions, superstitions, religions, love—seduction is a national pastime—literature, revolution and their passion for life. Because Ernest Hemingway loved this country and praised its people, in his books and in real life, Cubans have kept a special place in their hearts for the American writer. Fifty-odd years after his death this is still the case.

Ernest Hemingway at his home in Cuba, the Finca Vigia, circa 1947. Photos: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.

Hemingway spent some 22 years in Cuba. It is said that his roots ran deeper in this land than anywhere he lived, including Paris, Madrid, Key West, New York, Michigan or Idaho. It is no secret that he had a great admiration for the Spanish culture. He surrounded himself in it, spoke the language and practiced the traditions. And the Latinos never considered him a gringo, but one of their own. Old people I have met in Havana, Cojimar and San Francisco de Paula recall “Ernesto” in the kindest of favor.

There are still strong impressions of Hemingway in Cuba. These come out of his fiction, of course, but there is also the bust, the boat, the bars and cars, the marina, plus his beloved lookout farm, Finca Vigia. All stand as monuments to a fascinating icon; treasures that linger—though in a state of decay—on an island where time has stood still since before the people’s revolution began.

Hemingway’s Pilar, on display atop the former tennis court at Finca Vigia.

Americans refer to this period as the good old days before Fidel. But Cubans see it as a day that was less kind to its own, a time when gringo brothels thrived. And there was racism, enslavement, illiteracy and great humiliation.

Hemingway’s literary images become more authentic as years pass (the N-word in his prose was as common as the F-word is in today’s literature). Having traveled in this part of the Caribbean, I can see how true to life the sketches are.

Ernest Hemingway reading books with his dog, Negrita, at Finca Vigia. Photo: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.

When we think of pre-revolutionary Cuba, it is hard to ignore Hemingway’s fiction. He was able to grasp the movements of its people, their places on the fishing boats, in the cane fields, the towns, churches, the markets and the bars. Plus the absence of black people on busses, trains and in the city plazas. You would have to live here for some time—not as a tourist—to do it justice, which he did. Like portraits of Che, Fidel, Camillo and other heroes from the Revolution, Hem’s picture albums are sold to tourists at gift shops. There are Papa Hemingway T-shirts, shorts, sandals, fishing caps and sunglasses. In a sense, Hemingway is as much alive here today as he was in the 1940s and ’50s.

Left to right: Roberto Herrera, Byra “Puck” Whittlesey, John “Bumby” Hemingway, Spencer Tracy, Ernest Hemingway, and Mary Hemingway socialize at the El Floridita, circa 1955. Photo: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.

Plus, there is an aura that lingers: ’50s-model cars, hotels with window awnings, pink piano-shaped swimming pools and the spirits of American celebrities singing in Havana. Those were romantic times in the old white city of love. Men such as Frank Sinatra, Nat King Cole and Desi Arnaz performed at the Capri, a classic rooftop bar on Paseo Melecon. Writers including Hemingway, Graham Green (who stayed at Hotel Inglaterra and wrote Our Man in Havana), Alejo Carpentier and others could be spotted in the streets or at bars. The Tropicana, the world’s biggest outdoor night club, had the best chorus lines in the Americas. As Alina Fernandez (Fidel Castro’s daughter) wrote, Havana was the most feminine city in the universe.

Hotel Ambos Mundos in Havana. Photo: Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Hemingway came to Cuba in 1928 on a steamer out of France. He fell in love with the place. By 1936, he had moved into Hotel Ambos Mundos in old Havana and was wooing Jane Mason. Each day, he and Jane would walk up Calle Obispo to El Floridita, where they would sit with friends in the Red Room and drink daiquiris. It is said that Ernest used Jane as a model for Helen Bradley, the heroin in his novel To Have and Have Not.

Old Cubans remember Ernest as a stocky and bearded man, scuffling along in boat shoes, a woman on his arm. In the Ambos Mundos (now a refurbished hotel that honors Hemingway’s room as a museum), the American stood at a small table and used a lead pencil to write, For Whom the Bell Tolls, his novel set in Spain during the Spanish Civil War.

Hemingway at the wheel of the Pilar with the Havana skyline in the background. Photo: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.

By 1939, Hemingway had established himself permanently in Cuba. His third wife, Martha Gelhorn, introduced him to Finca Vigia (Lookout Farm), a colonial house built by a Spanish architect with 22 acres of cane fields in San Francisco de Paula. It was there that Hemingway lived until after the revolution.

Hemingway’s home down the coast from Cojimar where he moored Pilar, a boat he had built by Wheeler Shipbuilding of New York and named after the Spanish Saint. It was from that jetty, with Captain Gregorio Fuentes at the helm, that the writer set out on fishing expeditions for tuna, blue marlin and swordfish. During the ’40s, Fuentes and Hemingway rode out three hurricanes (winds of 180 miles-per-hour) on the Pilar, which was built to operate in the heaviest kind of water. It had a minimum cruising range of 500 miles and could sleep seven.

Hemingway wrote in Holiday magazine: “Gregario was the only man to stay on board a small craft in the October 1944 hurricane when small craft and navy vessels were blown up onto the harbour boulevard and up onto the small hills around the harbour (Havana).”

In 1947, Mary Walsh, Hemingway’s fourth wife, joined her lover in Cuba. In a letter to Mary, he wrote: “When you come in by plane from Miami, I will be waiting at Rancho Boyeros airport . . . and we will go in the car across this beautiful country to our home.”

Ernest and Gregory Hemingway at the Club de Cazadores in Cuba. Photo: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.

Upon arrival, Mary set out to renovate Lookout Farm, a place Hemingway said was his only real home. The two received many guests, but only rarely did Ernest share his place with other writers. It was there he wrote Across the River and into the Trees (1950) and The Old Man and the Sea (1952).

In 1950, the International Nautical Club of Havana held its first competitive marlin tournament and named it The Hemingway International Tournament of Marlin Fishing. Since then, each year this event takes place from its headquarters at Marina Hemingway in west Havana.

Captain Gregorio Fuentes and the author.

In 1999, when I retreated to Cuba for the winter to write, I visited Captain Fuentes, a man who was 103 years old but bright as a brass button. Fuentes was still living in the fishing village of Cojimar. The old man had been captain of Pilar for more than 20 years.

Fuentes told me that during World War II, he and Hemingway patrolled the islands in the Caribbean looking for German U-boats. They also searched for marlin as depicted in novels, Islands in the Stream and To Have and Have Not, the former drawing on the personality of Fuentes for its character, Antonio.

Hemingway later admitted that Fuentes was also a model for Santiago, the fisherman cursed by Salao (the worst kind of bad luck) in the novel The Old Man and the Sea, which won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954.

Hemingway at the Club de Cazadores in Cuba. Photo: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.

Fuentes told me that he and Hemingway were docked at Cayo Paraiso and came upon an old man and a youngster fighting a swordfish. They offered to give a hand but were refused. Fuentes believed the incident inspired his friend to write The Old Man and the Sea.

At that time, Fuentes was walking two blocks daily from his home to his favorite chair in La Terraza, a fisherman’s bar where he was served a mojito and a Habana cigar. He told me that he and Hemingway had drunk there for years.

As we sat in the place where Santiago and the Afro/Cuban arm-wrestled in the movie, people came to greet the old man. I was honored to be there beside him. The place was decorated with photos of Fuentes and Hemingway. There were also snapshots of Errol Flynn and Spencer Tracy. Behind the bar was a poster of a smiling Fidel Castro and Hemingway shaking hands.

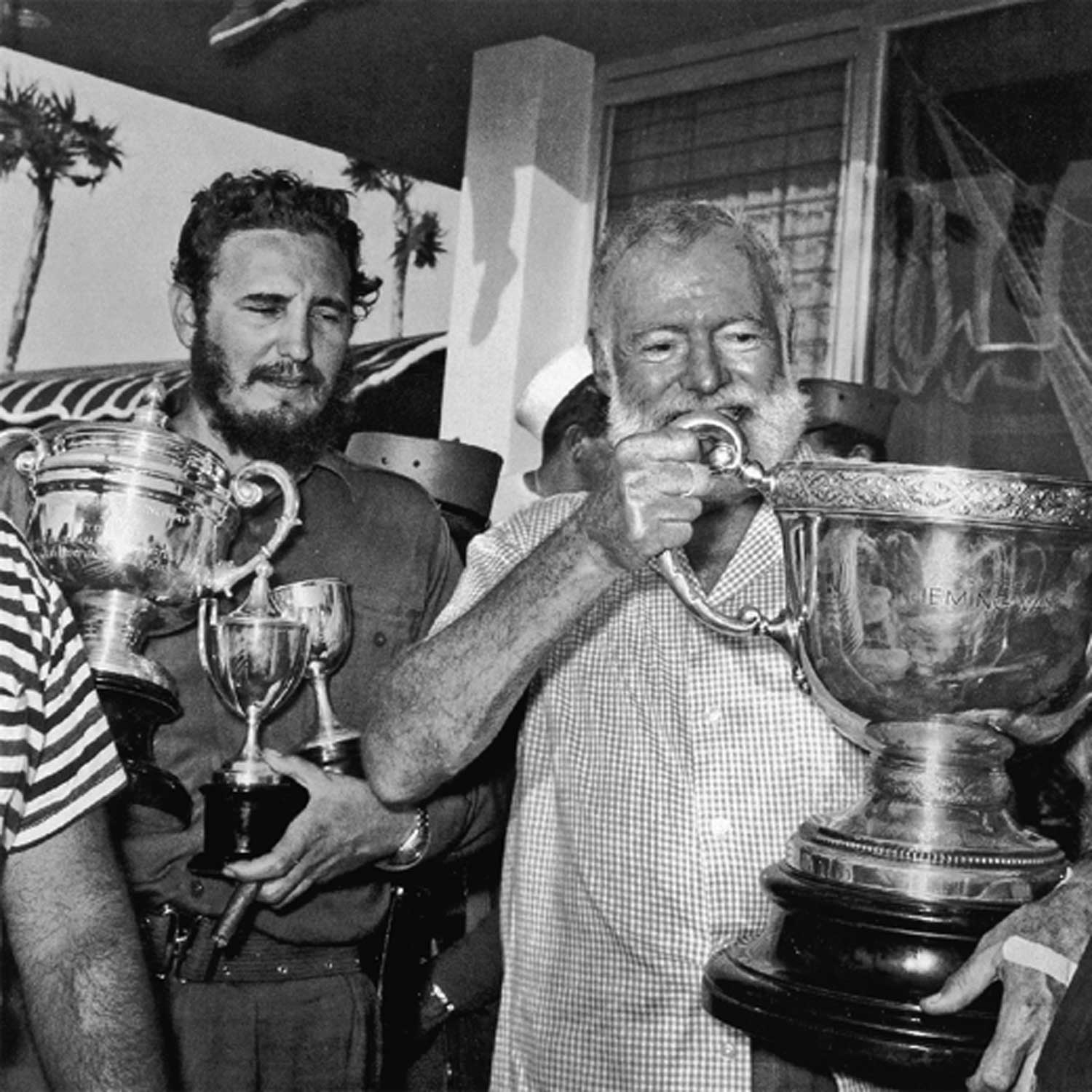

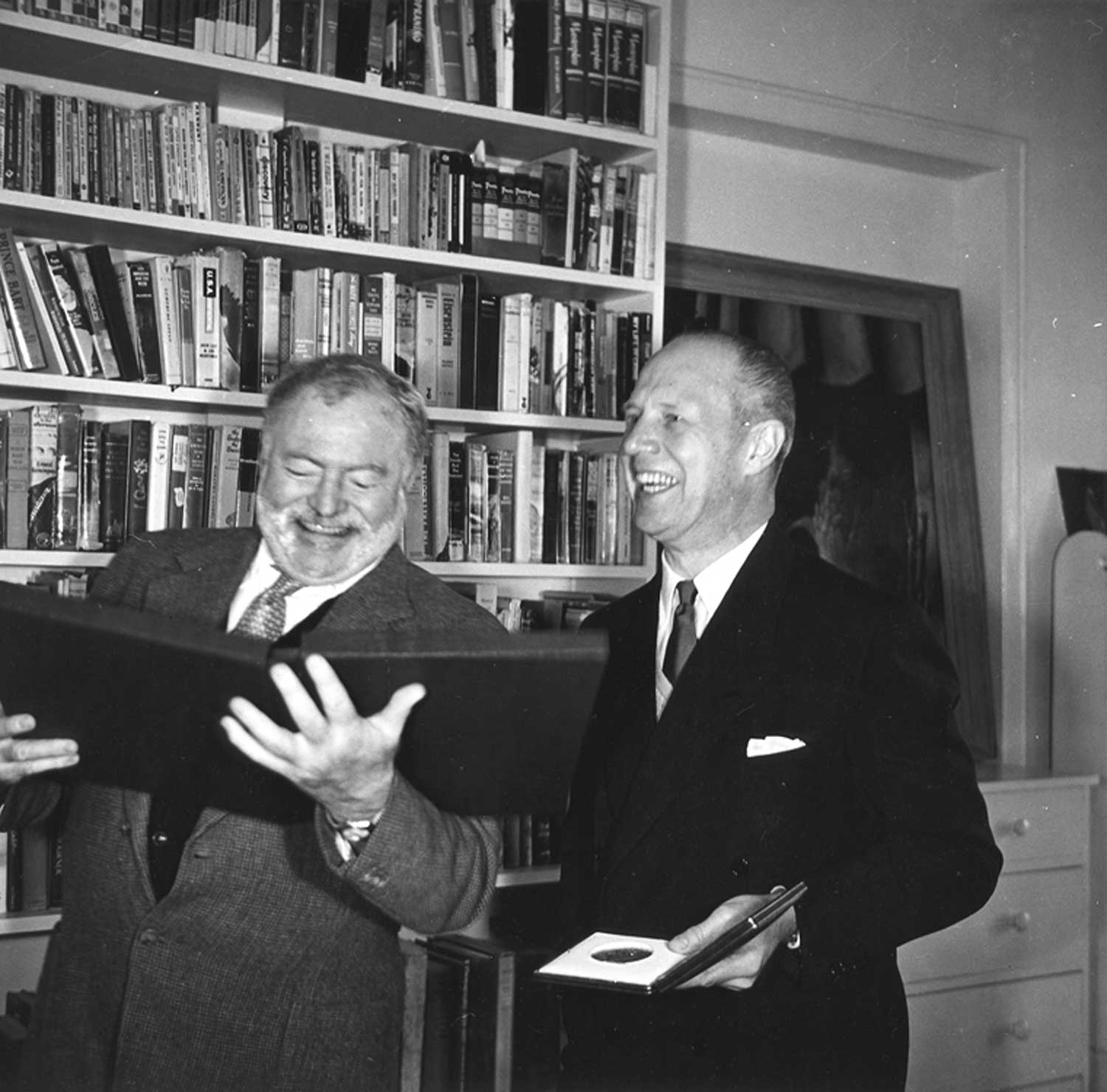

Fidel Castro and Ernest gather up trophies to be presented to winners of a Hemingway fishing tournament.

It is said that Castro (who had won Hemingway’s first fishing tournament), envied the writer because of the traveling he’d done. What’s more, Hemingway had supported Castro’s July 26th movement.

“I believe in the historical necessity of the Cuban Revolution,” he wrote.

Ernest Hemingway receives the 1954 Nobel Prize for Literature at his home, the Finca Vigia, San Francisco de Paula, Cuba. Photo: John Fitzgerald Kennedy Library, Boston.

Lookout Farm sits on a hill that gives onto the sea and is shaded by mango, avocado and ceiba trees. Tourists pay three pesos to wander around the grounds and look through windows at Hemingway’s guns, fishing rods, photographs of Ava Gardner, Ingrid Bergman, his editor Maxwell Perkins, Gary Cooper and heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano. The author’s glasses are lying on the desk where he wrote. There is a photograph of Hemingway on the day he won the Nobel Prize. More than 9,000 books crowd shelves that are so tall a stepladder is needed to reach the top.

In 1961, suffering depression, Hemingway gave his Nobel Prize to Nuestra Senora de la Caridad, the patron saint of Cuba’s only basilica in Santiago.

Upon his death, Mary Walsh graciously presented the house and grounds to the people of Cuba. The Pilar was given to Captain Fuentes and is on display at Finca Vigia.

Photo: Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Fishermen in Havana, Cojimar and San Francisco de Paula donated brass from their boats, which was melted into a bronze bust of the novelist. The monument looks out to sea a stone’s throw from La Terraza Bar where I was greeted so warmly by the real old man of the sea, Captain Gregorio Fuentes.

Time moves slowly in Cuba. During Mary Walsh’s final trip to Havana in 1977, she said, “Everything is just where we left it in 1961. But the house is nothing without Ernest.”

Note:This article originally appeared in the 2020 March/April issue of Sporting Classics magazine.

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature.

Hemingway on Fishing is an encompassing, diverse, and fascinating assemblage. From the early Nick Adams stories and the memorable chapters on fishing the Irati River in The Sun Also Rises to such late novels as Islands in the Stream, this collection traces the evolution of a great writer’s passion, the range of his interests, and the sure use he made of fishing, transforming it into the stuff of great literature.

Here, collected for the first time in one volume, are all of his great writings about the many kinds of fishing he did—from angling for trout in the rivers of northern Michigan to fishing for marlin in the Gulf Stream. Anglers and lovers of great writing alike will welcome this important collection. Shop Now