I’m still not sure who was more startled when our trails suddenly crossed, that big bull elk or me.

Bear Canyon. Iron Springs. The Beaver Slide. Cañones Creek, Grouse Mesa, Bandit Peak, and the great Poso Valley—all names of places I have come to treasure over the years while traveling in and out of the San Juan Mountains of northern New Mexico.

For decades I have continually returned to these places, sometimes to hunt, sometimes to fish, and sometimes to write or photograph this magnificent landscape and its wildly diverse flora and fauna. And now I had returned here yet again, this time in late August just before the annual rut kicked in, to do some pre-season scouting for the upcoming elk season.

I was with my longtime co-conspirators, Franks Simms and his big ranch dog, Crockett. Frank and I were armed only with our cameras and elk calls; but for his part, old Crockett considered carrying a camera beneath his canine dignity and preferred instead to dedicate his valuable attentions to more important duties, like trying to keep Frank and me out of the trouble we were sometimes prone to get ourselves into…or at least to take part in the mischief with us and enjoy it himself.

We had headed out at first light, bearing north up the Chama valley from the lodge, skirting the western fringes of the Pine Tree hayfields, then along Willow Creek road below Sawmill Canyon before climbing in the general direction of Charlie’s Lake and Bobcat Rock. We eventually swung back to the south down through Wallow Canyon and finally stashed the truck in a little copse of aspen and began weaving our way on foot through the thick oaks and up the northern spur of the high ridge that overlooks Poison Springs and Bookout Lake, two miles across the broad valley to the east.

As we approached the crest, with the shifting afternoon breezes in our faces, I happened to be a few yards ahead of Frank and Crockett when we picked up the crashing sounds of something in the oak brush barreling over the top toward us from the opposite side.

We all froze in our tracks, Frank and me with our cameras raised to our eyes and old Crockett crouched below us. Then suddenly, the most magnificent bull elk I had ever beheld broke from the oaks less than 30 yards above, catching me right out in the open.

His body was massive, and his antlers nearly beyond comprehension. His sleek coat was a rich, glowing amber, and his finely chiseled head and lush neck ruff were the color of deep, dark walnut.

As he skidded to a stop, he had me dead to rights, towering above me like some grand bronze sculpture. I just stood there motionless, with the thick brush and dark conifers directly behind me and the wind in my favor. He seemed at a loss as to what he had just run into, but then that seventh sense that all God’s forest creatures possess kicked in, and he realized something was amiss.

I knew I was in a precarious position, and that if he came for me, I had absolutely no place to go. I dared not turn and flee, for that might spark his herd bull instincts to chase me down.

Fully aware that the start of the rut was still a couple of weeks away, I actually thought for a moment about charging him, but he really didn’t look like the sort that would back away from a challenge. So I stood my ground, not out of any sense of bravado, but simply to preserve the status quo—and hopefully, myself.

I was so close to the giant bull that I could literally see the glint in his probing eyes as he cocked his head from side to side and turned his gaze in my direction, trying to figure me out. The overwhelming rush of excitement coursing my veins was countered by a compelling sense of clarity and wonder at what I was witnessing in the viewfinder, and I quickly focused the camera on his eyes and opened fire.

His head was raised and cocked, with his nose sifting the breezes and his piercing eyes sweeping the entire area around us. From somewhere at my back I could hear the subtle click, click, click of Frank’s camera as he too registered the moment.

As the old bull kept trying to figure me out, I continued to shoot in earnest as his distinctive aroma wafted to me on the wind.

The smell of a big bull elk is something that, once you have experienced it, becomes deeply embedded in your mind. And now as his scent enveloped me, recollections of elk past began seeping into my memory. But for him, the wind was all wrong.

His nose was held high, desperately seeking any olfactory clue that might provide final verification of what his eyes were trying to tell him. For an instant, I was reminded of my faithful little bird dog Betsy, who never fully bought into anything until she validated it with her nose. I was alert for any sign of aggression in his face or eyes or body posture. But all I could detect was caution and confusion as my breathing and heart rate slowed and my focus shifted from survival to making sure I was taking full advantage of the remarkable photo opportunities at hand.

And then he busted me.

Perhaps he picked up the movement of my fingertips easing across the face of the camera and its controls. Perhaps he detected the subtle sounds of the shutter release as again and again I fired. But in reality, I think it was most likely the fickle breezes that finally betrayed me, carrying my scent to him. Whatever it was, he abruptly whirled back along his own track and disappeared into the dense oak brush.

My first impulse was to sprint up to where he had been standing moments earlier and then attempt to follow him. But instead, I broke parallel with him to the left, hoping to cross below him and perhaps get one or two more shots before he vanished into the oaks.

To my great delight, his exit path took him through an opening less than 15 yards above me, just below the crest of the ridge. Once again my camera came up of its own accord and began firing, just before he dropped over the edge and disappeared back down the face of the ridge.

The whole encounter had lasted only 20 or 30 seconds…45 at most. With my camera now dangling loosely in one hand, I turned and spotted Frank coming up from behind me with an expression of amazement spread across his face, and we both broke into great peals of adrenaline-laced laughter at what we had just witnessed.

As for Crockett, in all his dog years he had never seen such a sight—his favorite pair of two-legged, sub-canine companions standing face to face with this immense and imposing behemoth of a creature looming above them, and nary a rifle to be had. But thankfully, the daunting prospects of having to save his human charges from that giant, man-eating elk were now past. And so he just stood there and stared at us, somewhat disdainfully it seemed, then shook his big furry head and ambled out on the ridge ahead of us.

And as for that old elk? To this day, I’m still not certain who was more surprised by our chance encounter—me, Frank, Crockett, or him. But in the end, we all found ourselves with one heck of a story to tell.

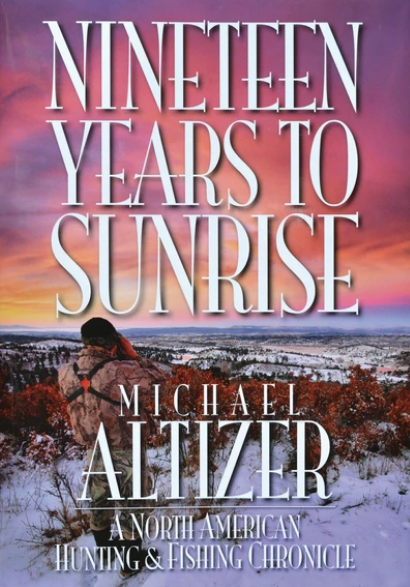

Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a

lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of

Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys.

And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now

Nineteen Years to Sunrise is an intimate and insightful collection of stories from a

lifetime of hunting and fishing across North America – from the forests and rivers of

Alaska and the great Canadian Shield, to the American West and the Florida Keys.

And, as you will read in these pages, quite nearly from beyond. Buy Now