Would you choose the Model 1866 lever-action, Winchester’s first rifle and the world’s first really successful repeater? Or would the Model 1873, the “Gun That Won The West,” be more representative? What about the M94, the best-selling hunting rifle in U.S. history? But that overlooks the Model 1885 single-shot, still being manufactured, a 130-year-old rifle that handles the highest powered, modem sporting rounds on the market. The 1885 has been chambered for more cartridges than any other rifle in Winchester’s line and probably anyone else’s, too. Then there is the Model 70, America’s Mauser, the Rifleman’s Rifle, still the undisputed classic and arguably the finest mass-produced, controlled-round feed bolt-action sporting rifle of all time.

Winchester Model 70

It may not be fair or even wise to define Winchester with a rifle at all. The company has also created some of our most enduring shotguns. A good example is the Browning-designed Model 97 pump, so reliable and efficient it initiated the demise of the double and contributed mightily to the “3-shot maximum” rue for waterfowling. It was superseded by the beloved hammerless Model 12, king of the pumps through much of the 20th century. Then there was John Olin’s Model 21, considered as the best side-by-side double ever built in the U.S.

Of course, Winchester has given us some of the greatest hunting cartridges of all time, too. They started with the .44 Winchester Centerfire, better known as the .44-40. Chambered in the 1873 as well as single-action revolvers of the day, the .44-40 went on to kill, some say, more game and people than any round until, perhaps, WWI. Some of Custer’s adversaries used it at the Little Bighorn. Custer’s troops probably wished they had. While anemic compared to today’s magnums such as the .454 Casull, the .44-40 is still deadly, still manufactured and still firing.

Winchester Model 94

More impressive is the .30 WCF, better known as the .30-30 Winchester. Introduced in 1895 in the M94 lever-action, the .30-30 was the first commercial sporting cartridge loaded with smokeless powder. It shot so fast Winchester created the first gilding metal jacketed bullets just for it. The round remains among the country’s top ten sellers and has been credited with taking more deer than any other centerfire cartridge.

But Winchester’s cartridge selection was just getting started. They brought to market the .22 Hornet, .220 Swift, .243 Winchester, .270 Winchester, .308 Winchester, .300 Winchester Magnum, .338 Winchester Magnum and .458 Winchester Magnum, among others. Three of those are the most popular in their categories and loaded by just about every rifle-maker and ammo factory in the world.

Without getting into shotshell and rimfire innovations, we can safely say Winchester hasn’t done too badly for a company started by an American who never built a firearm and never designed a cartridge.

Oliver Winchester, born 1810 in Boston, was a master carpenter, men’s garment retailer and then shirt manufacturer. Around 1855 he saw potential in a small company building an innovative repeating rifle called the Volcanic. It loaded from the breech and fired caseless ammo. The hollow bullets were stuffed with blackpowder and sealed with a percussion cap. The whole shebang departed the muzzle at the drop of the hammer, but not very fast. The bullet generated only about 60 foot-pounds of energy, so the Volcanic languished. But it pointed the way forward. Winchester saw the potential, took full control of the company, reformed it as New Haven Arms Company in 1857, and set plant superintendent B. Tyler Henry to work improving the whole repeating rifle concept.

The Industrial Age was in full flower in the 1850s. The Mississippi was bridged and railroads pushed as far west as Kansas, hinting at the first transcontinental rail line to California where the gold discovered by the’ 49ers was still emerging. A new medium called photography was the rage in New York City, but running water had yet to make it into kitchens. Edison’s incandescent light wouldn’t emerge for another 24 years. Nature’s call was answered after a quick run to the backyard privy. Lincoln wouldn’t be president for another five years. Our Civil War was looming, and it would Iargely be fought with muzzleloading percussion rifles.

This was still the blackpowder era, and firearms were rather primitive. The old flintlock ignition system had only just been superseded by the invention of the percussion cap in 1820. The first metallic cartridge popped up in 1845 when Frenchman Flobert pressed a BB atop one of those caps to create a parlor gun. Smith and Wesson didn’t stretch this to make their .22 Short until 1857.

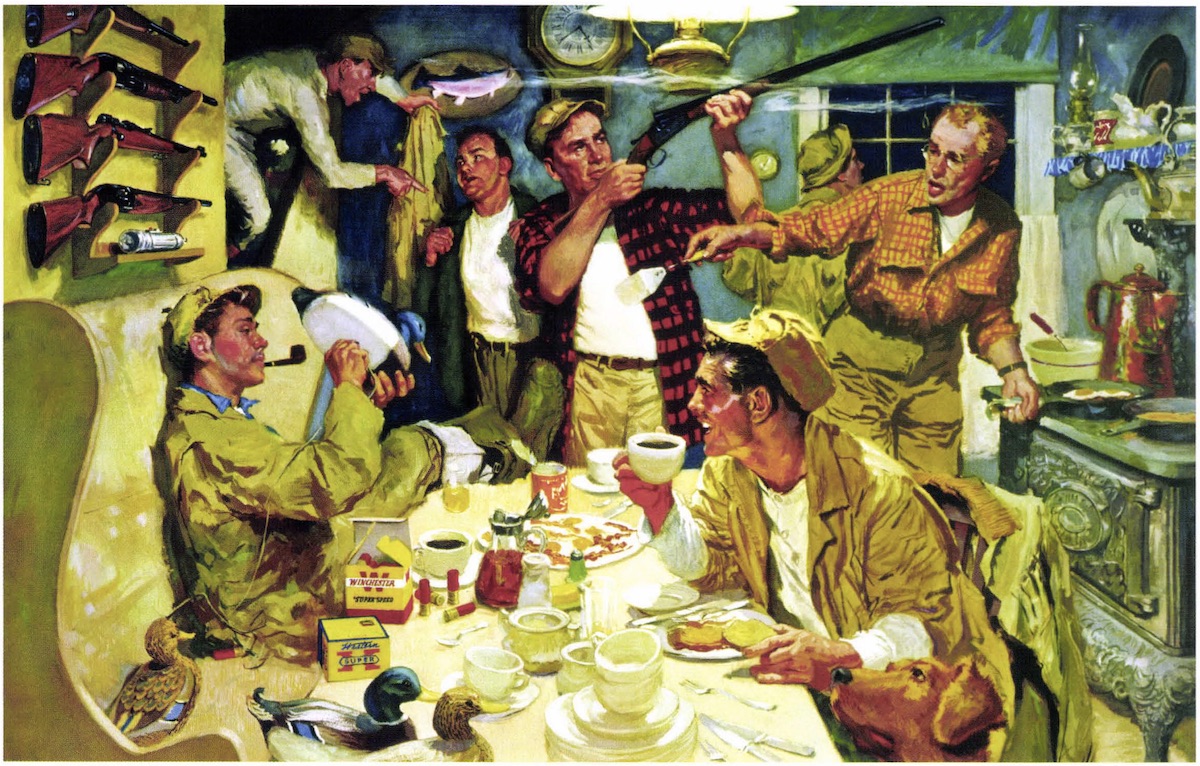

Winchester Breakfast At The Duck Club courtesy winfieldgalleries.com.

At New Haven Arms, Henry seized on this brass cartridge idea, combined it with the Volcanic repeating mechanism, and in 1860 patented the lever-action Henry Rifle firing the .44 Henry Flat rimfire cartridge. About 14,000 were eventually manufactured. A few thousand saw limited action during the Civil War, and many were used to good effect at Custer’s Last Stand by the Sioux and Cheyenne.

After Henry left New Haven Arms in 1864, Winchester tasked gunsmith Nelson King with improving the rifle. King closed the magazine tube to protect the coil spring, built a loading port/gate in the side of the receiver so rounds could be shoved forward into the tube and added a wood forend.

Winchester changed the company name to Winchester Repeating Arms and released this new iteration lever-action as the Model 1866. Built around a bronze frame, the gun soon became famous as the Yellow Boy, and Winchester was on its way to icon status, virtually a synonym for a repeating, lever-action rifle, the gun that would win the West and funnel millions of dollars through Hollywood.

Oliver Winchester died in 1880, three years before his son-in-law, Thomas Bennet, discovered John Moses Browning and began that fruitful association. Over the years Winchester has flourished and died several times, always rising like a phoenix. The name is just too good to let go. For a time after WWI it merged with a hardware company to manufacture everything from Winchester knives and ice skates to fishing reels and kitchen appliances.

When the stock market crash of ’29 put it into bankruptcy, John Olin of Western Cartridge Company bought it, merging the two brands Winchester Repeating Arms had been trying to amalgamate for years. Under Olin’s leadership, Winchester went on to great success and innovation for several decades before production costs, primarily labor, threatened insolvency. That was averted when Winchester employees bought the New Haven plant, incorporated as U.S. Repeating Arms, and licensed the Winchester name to continue production until 1989. It was then bought by a French holding company and soon sold to Belgian’s Herstal Group, which also owns Browning Arms Company and Fabrique Nationale.

Winchester Model 1895

Throughout it all, the Olin corporation kept the ammo business, which remains independent of the firearms to this day, confusing the heck out of people.

In 2006, with every Winchester rifle costing more to make than it sold for, the New Haven plant was closed, but the company stayed in business selling shotguns, an autoloading rifle and limited edition rifles made by Miroku Corp. of Japan.

In 2008 Fabrique Nationale announced it would build to the highest quality standards on the newest CNC machinery at its new plant in South Carolina Winchester M70s and, later, M94s, the company’s flagship rifles. With that change, U.S. Repeating Arms was changed back to Oliver Winchester’s original Winchester Repeating Arms Company.

Obviously, keeping any company viable for 150 years isn’t easy. But Winchester has done it, in the process creating iconic firearms beloved by their owners and passed down grandfather to grandson. Winchester Ammunition and firearms have inspired the continuation of an American heritage, a tradition of wildlife appreciation and sustainable use, a conservation ethic unique to the world.

Firearms expert John Taylor offers a global view of shotguns using photographs and descriptions of guns from the U.S. and many European countries. Sections include how to care for and store your gun, available accessories, and travel cases. Shop Now