In 1985 Holland & Holland bought W&C Scott of Birmingham, a purchase that brought together two of the oldest and most influential gunmakers in England — two firms that helped create the modern gun and thus helped shape tradition.

And then Holland & Holland did a remarkable thing: It converted the Scott factory to a high-tech operation where best-quality guns are built to computer-generated design by computer-controlled milling machines, spark eroders and other Space-Age stuff.

Arch-traditionalists were aghast. What could be more alien to the centuries-old conventions of the trade? How, they asked, could a best London gun possibly be built by computer when the whole tradition centers on sporting guns built by hand?

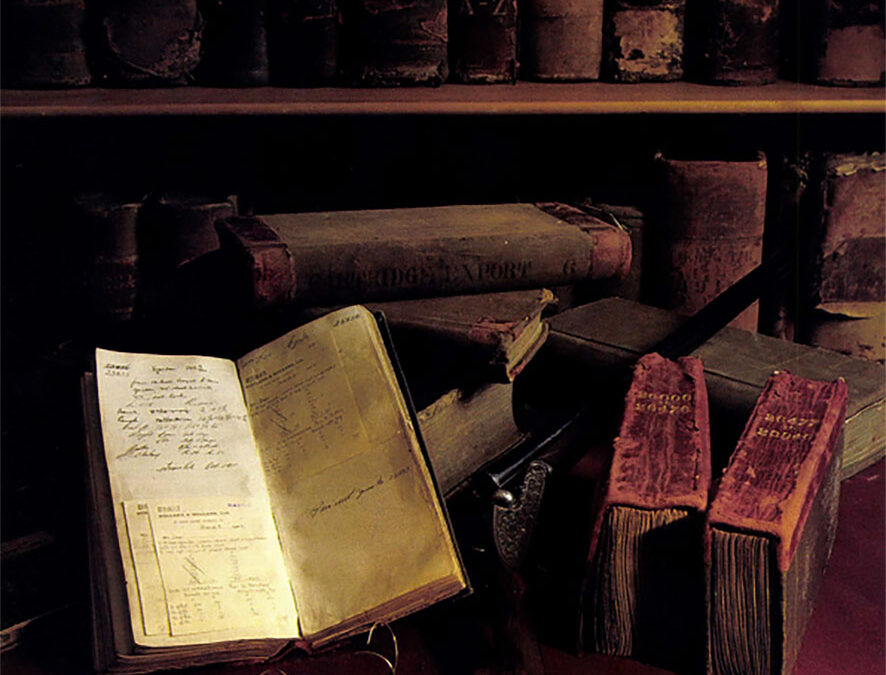

Holland & Holland archives date back

to 1830s. This is a Cavalier Deluxe.

Tradition does celebrate the handmade gun, but in that, tradition is misleading. And Holland & Holland has a tradition of its own — 150-odd years during which the unconventional has often been the rule.

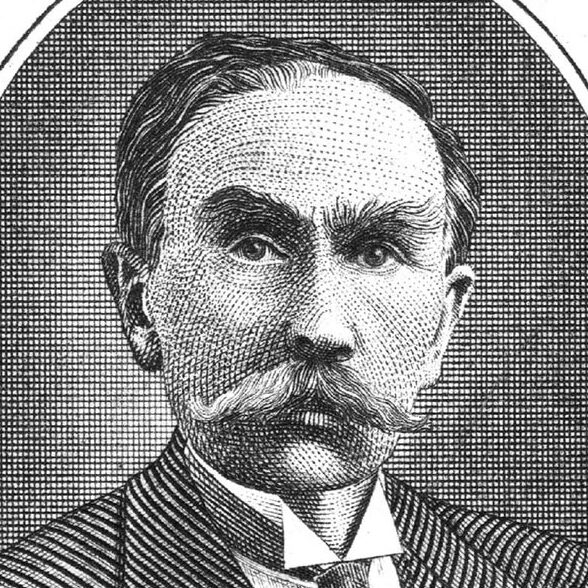

Harris Holland wanted to be a professional musician. He became a tobacconist instead, and by the end of his life, he was one of the most important gunmakers in England.

How it happened isn’t entirely clear. Unlike virtually all of the finest craftsmen of his generation, he was neither apprenticed to nor employed by Joseph Manton or a Manton disciple. In fact, no evidence remains to show that Harris Holland served an apprenticeship with any gunmaker. Both his taste for music and the talent for working with his hands may well have come from his father, an organ-builder; how he came to choose the tobacco trade is anyone’s guess, but choose it he did, and opened a shop at 9 King Street, London, in 1835. He was 29.

J 2-bore Deluxe Game Gun. Years ago, H&H sold a vast variety of firearms, even punt guns and harpoon guns.

The sot-weed earned his living, but shooting touched his heart. Harris Holland was a keen sportsman, known around the London pigeon-shooting clubs at Old Red House and Homsey Wood as a first-class shot. A number of the best London gunmakers, James Purdey among them, were pigeon shooters, too, and their acquaintance may have prompted Holland to have a go at making a gun or two himself.

One version of the story has it that tobacco-shop customers put up the cash to finance his entry tot he gun trade. According to another version, the king of Italy provided the capital. At any rate, by 1850 the King Street premises had become a combination tobacco shop, gun shop and gentleman’s club, and Harris Holland was a gunmaker.

In the English trade, the term gunmaker has more often meant “gun retailer” than “gunsmith.” The man whose name appears on the finished product may have taken no part at all in the actual hands on work of building it, acting instead as an executive who obtains component parts from specialized craftsmen — lockmakers, barrel-makers and others customarily known in the trade as “material men.” He then contracts work from other craftsmen, “fabricators,” who assemble the various parts into finished guns. The “gunmaker” then sells them under his own name.

Which is not to say that gunmakers have been office men who never touched a file or chisel. On the contrary, by far the majority of them learned the trade as apprentices or employees to some other maker and once established in business on their own, did much of the fabrication work themselves, at least until they became successful enough to employ a staff of craftsmen. This is still the case today in small shops such as Wilkes and Symes & Wright, where the man whose name appears on the guns does at least part of the work that goes into them.

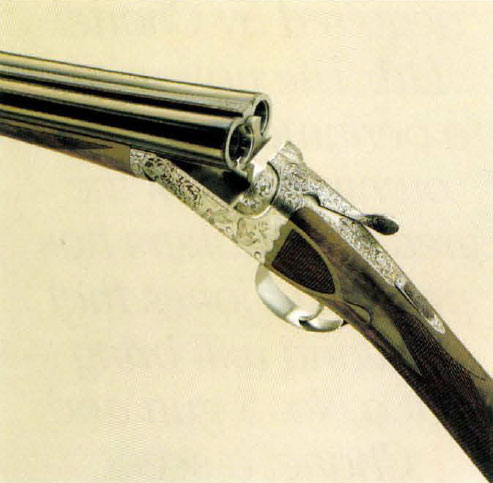

Holland & Holland’s beautiful Royal double.

In the beginning, Harris Holland worked more as a retailer than as an actual gun-builder. About 1860, he brought in his nephew as an apprentice. Henry Holland was 15 at the time. By 1866, business was good enough that they moved to more fashionable quarters at 98 New Bond Street. Henry Holland completed his indenture the following year and probably become a working partner at the same time, although the firm did not adopt the style Holland & Holland until 1876.

Even when he is not an active craftsman, a gunmaker builds his reputation on the quality of work to which he is willing to put his name, and throughout his career, Harris Holland demonstrated both a keen sense of quality and a shrewd regard for what constitutes a desirable, sellable item. Much the same approach, in fact, has characterized Holland & Holland ever since, and skillful management, the lack of which has brought many another English gunmaker nearly or truly to ruin, has been a key factor in Holland’s survival in the turbulent 20th century.

Harris Holland retired in 1876, turning day-to-day management over to his nephew, although he maintained control of the business for as long as he lived. Henry Holland proved not only to share his uncle’s business sense but also to be a clever designer as well. Through the 1870s and ’80s, as the firm continued to sell guns and rifles built on patents held by Thomas Perkes, W&C Scott, and many others, Henry Holland obtained several patents of his own. Some of his inventions — a game-counter, a measurement-gun and a try-gun — contributed little or nothing to the evolution of either the gun or of Holland & Holland. Other designs, though, eventually would combine as the distinctive and classic Holland gun.

He also was shrewd in his choice of collaborators. In 1879, Holland and Thomas Perkes jointly patented a pivoting-slide safety system for hammerless guns, and in 1897, he collaborated with Thomas Woodward on a three-pull, single-trigger mechanism. The most fruitful association, however, came during the I 880s, between Henry Holland and John Robertson.

Robertson, the son of a Scottish gun making family, spent 10 years working for James Purdey the Younger before setting up about 1880 in George Yard, Wardour Street, as an outworker to the London trade, building guns for Grant, Lang, Holland and others. In 1891 he became a partner in Boss & Company, in 1909 designed the splendid Boss over/under, and ultimately came to own the Boss firm outright. In the ’80s, though, he was busy at his own devices — building guns, designing locks and actions.

Although he and Henry Holland collaborated on an excellent ejector system, covered by two patents issued in 1887 and a third in 1888, their most important joint project was the first, a hammerless action patented in 1883.

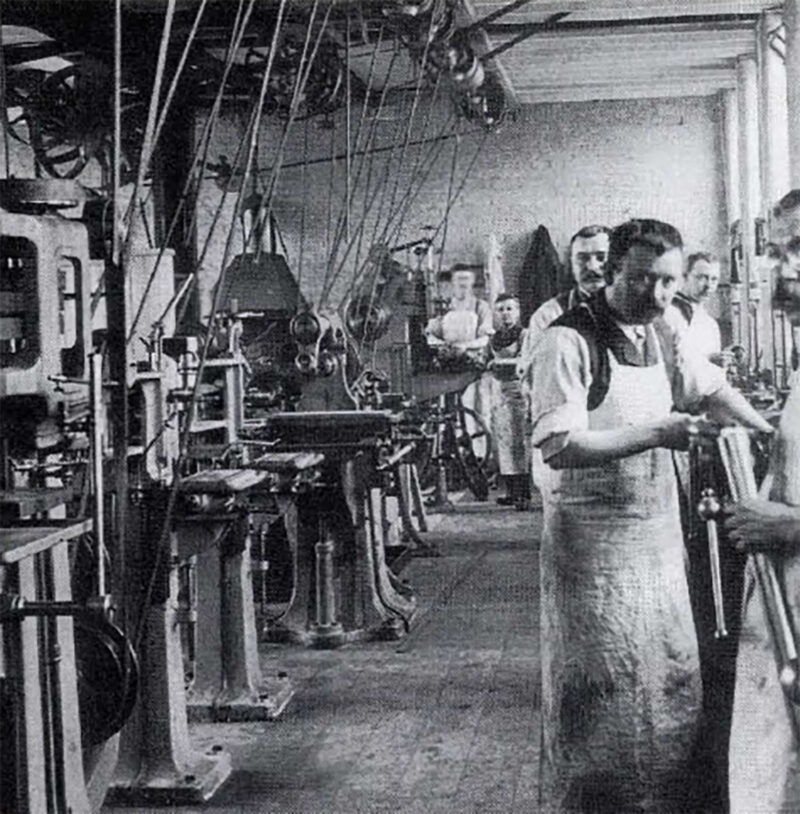

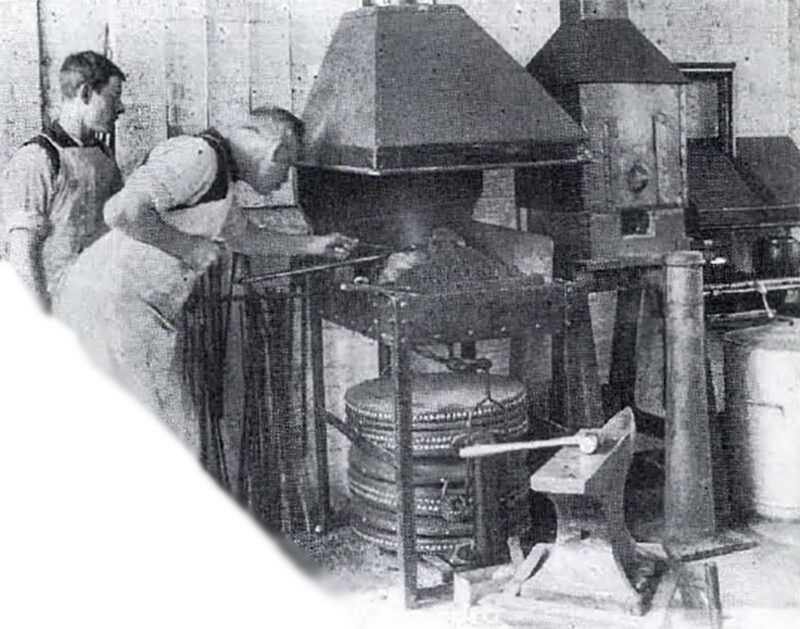

Factory scenes shortly after the turn of the century when H&H began manufacturing

most of what it sold.

After the Anson and Deeley system of using barrel-leverage for cocking was patented in 1875, the British gun trade went on a rampage of invention. From 1876 through 1890, 136 different patents were issued on designs for hammerless actions — 23 of them in 1879 alone and 50 more over the next three years. Not all were equally good, of course; most, in fact, soon faded to obscurity. But the spate of new ideas also created some classics, and the Holland-Robertson action was one of them.

The original design describes a mechanism that cocks the right-hand lock as the action is opened and cocks the left one as it’s closed. Maximum leverage can thus be applied to each lock separately, rather than to both at the same time, and the system also equalizes the effort a shooter must expend in operating the gun. Its disadvantage is that the mechanism has to be somewhat different from one side to the other. In Holland’s design, the left one is more complex and therefore more likely to malfunction.

The alternate-cocking idea — which some other makers also tried — didn’t last long, but the Holland Robertson helped create the famous Holland Royal action in which both locks work the same way as the right-hand lock of the original design. It now is one of the standard actions for sidelock guns, widely copied even today by makers in England and Europe. The first of the ejector patents awarded to Holland and Robertson in 1887 also describes the intercepting safety that the firm advertised widely as the Holland Patent Safety Lock. It, too, is still used in the Holland Royal gun and similarly has been copied nearly everywhere since its patent protection expired.

Through the last two decades of the 19th century, Holland & Holland sold a vast variety of firearms- game guns; wildfowl guns of 8-, 4- and even 2-bore; rook rifles; big-game rifles; punt guns; yacht guns; harpoon guns; and a revolving percussion rifle designed on the order of the early Colts. By the time Harris Holland died in 1896, the company owned the New Bond Street shop, shooting grounds outside London, a 15,000-square-foot factory on Harrow Road and a superlative reputation the world over.

Acquisition of the factory in 1895 marked a turning point. Although Holland’s continued to sell guns by other makers, for the first time it was manufacturing most of what it sold, building various models of the splendid Royal hammerless gun, double and single-shot rifles of all description, backlock game-guns and the famous Holland Paradox, a smoothbore gun with rifled muzzles that could serve both for bird-shooting and big-game hunting.

Acquisition of the factory in 1895 marked a turning point. Although Holland’s continued to sell guns by other makers, for the first time it was manufacturing most of what it sold, building various models of the splendid Royal hammerless gun, double and single-shot rifles of all description, backlock game-guns and the famous Holland Paradox, a smoothbore gun with rifled muzzles that could serve both for bird-shooting and big-game hunting.

By the turn of the century, only Purdey could rival Holland & Holland in reputation and as a holder of royal warrants. Holland’s has served by appointment as gun and riflemakers to Edward VII and George V, to King Alfonso XIII of Spain, to the Czar of Russia and the kings of Italy, Sweden and Portugal. Currently the firm is, by appointment, riflemaker to H.R.H. The Duke of Edinburgh.

Britain’s prosperity carried through the first 14years of the new century, and like the gun trade itself, Holland & Holland prospered along with it. Whatever the firm touched, it seems, turned out a success. In 1904, Henry Holland patented a design for a cartridge case with a reinforcing belt at the base. The two proprietary cartridges that resulted — the 300 Holland & Holland, which the firm has always called the Super 30, and the 375 Holland & Holland — became classics almost overnight. The 375 still is the most widely used big-game cartridge in the world. The British gun trade never fully recovered from the horrors of World War I and the economic miseries that followed — not because the quality of its products declined, but rather because its old markets in Europe and Asia and the Far East were in shambles.

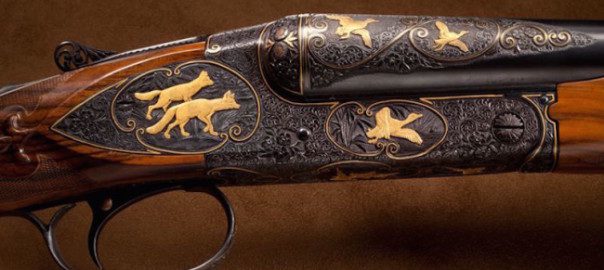

Canvas of steel, an elegantly rendered African lion graces the sidelock of this H&H Royal Deluxe rifle.

Henry Holland died on January 25, 1930, and his son Jack took over the company, just as the world economy began a 10-year slide that ended in yet another, unimaginably devastating global war. Afterwards, the traditional markets for best-quality guns revived even slower than before, and when they did, shortages of high-quality wood and steel and ammunition made filling orders a difficult task. Changing political climates in Africa, India and the Far East slowly eroded those once-lucrative markets, and like other British gunmakers, Holland’s soon found that much of its hope for the future lay in America.

That meant, for one thing, an over/under gun, and Holland’s built 26 of them during the 1950s, sidelocks based on the Royal action.

When Jack Holland died in 1958, the family’s role in managing the firm came to an end. The following year, Holland’s, the Westley Richards’ London agency, the Farlow fishing-tackle works and WJ. Jeffery, the great London riflemaker, amalgamated to form a holding company with Malcolm Lyell as managing director. A year after that, in 1960, Holland’s moved to 13 Bruton Street, refitted its Harrow Road factory with updated equipment, instituted more efficient manufacturing techniques, began making better use of the shooting school as a marketing tool and generally expanded its marketing efforts worldwide, with special emphasis on the United States.

Neither Harris nor Henry Holland could have figured a better way to keep a fading industry afloat in a new and far less genteel world. For the most part, the gunmakers that were unable or unwilling to accommodate a world economy where diverse and aggressive marketing is the rule of survival didn’t last much past 1970. Even those that did had no easy time of it, for as factory-built Japanese and Italian and Spanish guns came more and more to dominate the world market, the share left over for the classic London gun, finely crafted and painfully expensive, continually shrank.

As if to commemorate the passing of an era — and in so doing, perhaps to slow the rate of its passing — Holland’s in the mid-1960s began a series of collector’s pieces under a program titled Products of Excellence: one-of-a-kind individual guns and sets of various description, meant in their diversity of form and decoration to celebrate aspects of the gunmaking tradition. So far the series includes, among many others, a 12-bore game gun dedicated to the Goddess of Hunting, the last Holland 600 Nitro-Express double rifle, a pair of 4-bore hammerless ejector guns, a 28-gauge in honor of the quail, and the first two pieces in a sub-series commemorating the great African hunters — Royal Ejector double rifles in 500/465 Nitro Express, one dedicated to Sir Samuel Baker and the other to Frederick Courteney Selous.

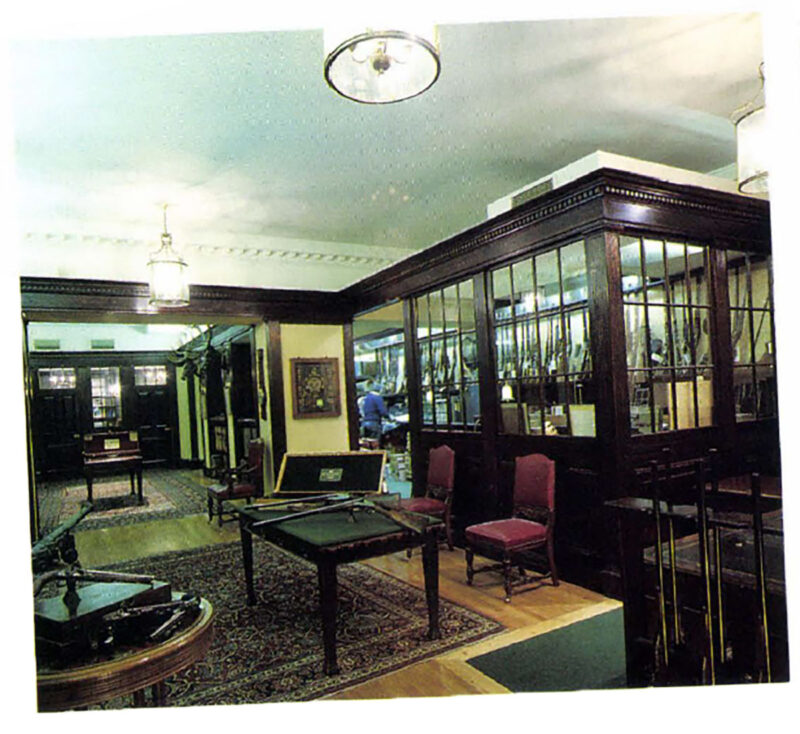

Holland’s moved to its present location at 33 Bruton Street in 1984 and last year expanded to include No. 31 as well — extremely handsome, well-appointed quarters where all the elegant traditions of English gunmaking seem palpably alive. And indeed, they are, but something else is alive there as well, something no other best-quality English gunmaker has ever attempted.

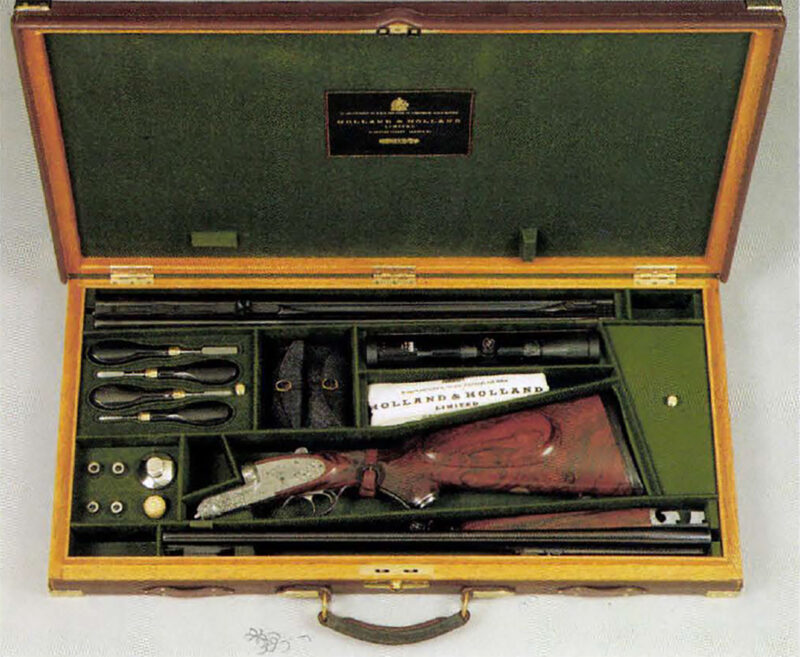

Same gun, a .458 double with extra .375 barrel, reposes in its immaculate oak and leather case.

Tradition has it that best-quality English guns are, almost by definition, built by hand. Few actually ever have been, since the days of Joe Manton and even before, because every gunmaker with any business sense at all has sought to do as much preliminary work as possible by machine. And in any case, final fit and finish is where handwork is the key; artistry in gunmaking is a matter of concept and of the last few thousandths of an inch, not in the means by which a block of steel or a slab of wood is roughed into the shape of a frame or a stock.

Holland ‘s first products of space-age technology, boxlocks called the Northwood and Cavalier, are excellent pieces, but they have been unable to buck the old prejudice — which the London gun trade did much to create — that considers boxlock guns inherently inferior to sidelocks. As is the nature of prejudice, that view has no basis in fact, but there it is, and Holland’s discontinued its boxlock guns at the end of last year.

In their stead will come two over/unders — one a Royal-action sidelock in 20 gauge and the other a boxlock 12-bore designed for sporting clays. The classic Holland side-by-side game gun, built the traditional way, remains available as well: the Royal Ejector at £24,250, about $47,000, and a Royal Deluxe, for about $9,000 more.

Holland’s is breaking some new ground on the rifle side, too, in response to the current wave of interest in big bores. About 1985, an American collector requested a .600 Nitro-Express double. The company declined, saying that it could not in good conscience do so, since it had in 1974 built and sold the commemorative .600 with the promise that it would be the last. The man then asked for a 700 Nitro-Express and Holland’s replied, quite truthfully, that there was no such thing.

Holland & Holland showroom at 33 Bruton Street in London.

In a joint venture, Holland’s and the former Brass Extrusion Laboratories Ltd. have created both a new big-bore cartridge and a rifle to hold it. The rifle, which was test-fired from the shoulder for the first time on November 21, 1989, and completed shortly after, is a 19-pound Royal de Luxe double. I saw and handled the piece in London. BIG, beautifully built and proportioned. The cartridge is a flashlight-sized affair made up in a 3 1/2-inch case that holds a1000-grain bullet. The ballistics are impressive, too: muzzle velocity of 2000 feet-per-second for 9050 foot-pounds of energy That’s nearly 1000 foot-pounds more energy than the 460 Weatherby Magnum, which no longer holds the title as the world ‘s most powerful commercial cartridge.

Hardly a useful item, in practical terms, but valuable nonetheless, since the present interest in African rifles and African hunting can only help preserve what remains of a great tradition. And the first 700 won’t be the last; Holland’s holds orders for three more — at roughly $100,000 apiece — to be completed by the turn of the 21st century.

What that century is likely to hold for the British gun trade in general is largely uncertain but, for Holland’s, at least, there are hopeful signs. Holland & Holland became a wholly owned subsidiary of Chanel Ltd. and notion of a perfume company owning one of the world’s great gunmakers has prompted differing reactions and inevitable jokes that Holland’s will soon bring out a No. 5 gun, while Chanel plans a new scent called Nitro. Modern economics, like politics, makes strange bedfellows, but the important thing is that Holland & Holland maintains a measure of security in a world that’s been brutally hard on the greatest gun trade in history. If the tradition is to survive in the future, it must do so on 21st century terms. That’s how tradition survives anyway — by preserving gold values while accommodating new times.

Gun Craft examines today’s artisanally made guns, as well as the craftsmen who make them. In it, the author takes the reader into the workshops and factories of the world’s best gunmakers, making their sometimes-arcane craft skills accessible and relevant to anyone who shoots, owns or collects fine guns. Each chapter explores a separate topic; each has been chosen, however, to provide readers with a unified insight into the complicated task of making hand-made guns in both Europe and the United States. Buy Now

Gun Craft examines today’s artisanally made guns, as well as the craftsmen who make them. In it, the author takes the reader into the workshops and factories of the world’s best gunmakers, making their sometimes-arcane craft skills accessible and relevant to anyone who shoots, owns or collects fine guns. Each chapter explores a separate topic; each has been chosen, however, to provide readers with a unified insight into the complicated task of making hand-made guns in both Europe and the United States. Buy Now