In autumn 1858, on a beautiful day in the Scottish Highlands, a remarkable sporting feat that would be recounted innumerable times until passing into legend, occurred.

During dinner the previous evening at the Duke of Atholl’s estate, Sam Baker, recently returned to Britain after years in Ceylon, promised assembled guests a unique approach to deer stalking come morning. His boast, possibly fueled by the laird’s libations, involved such daring news spread rapidly to nearby villages, and when the hunting party set out with September dews sparkling in the glens, a bevy of spectators had gathered. Rustic rubbed elbows with ladies “resplendent in crinolines” in a setting where fall cloaked the Highlands in green and gold, scarlet and russet as silvery birches whispered, and morning thermals teased crystal-clear Tilt River’s surface.

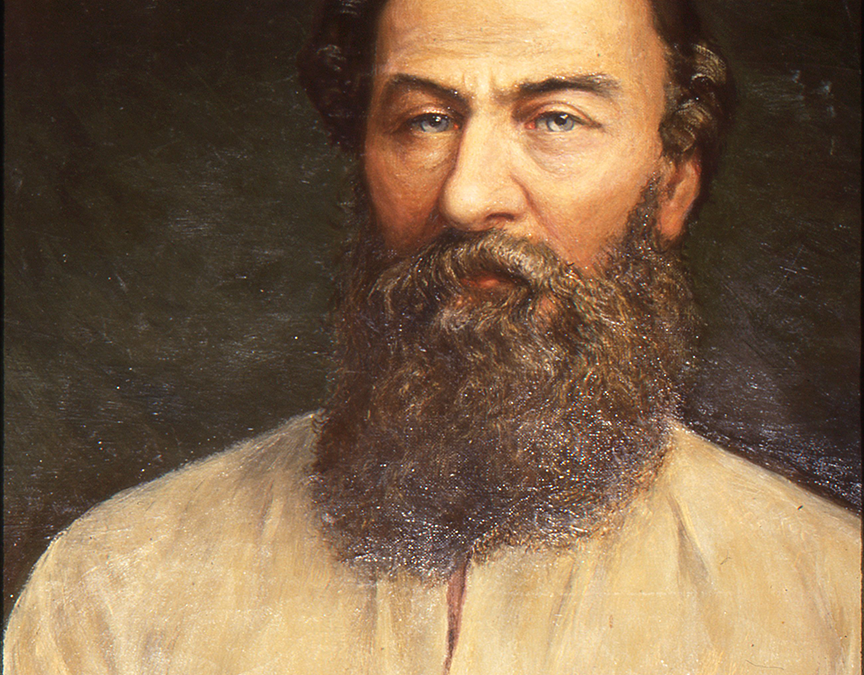

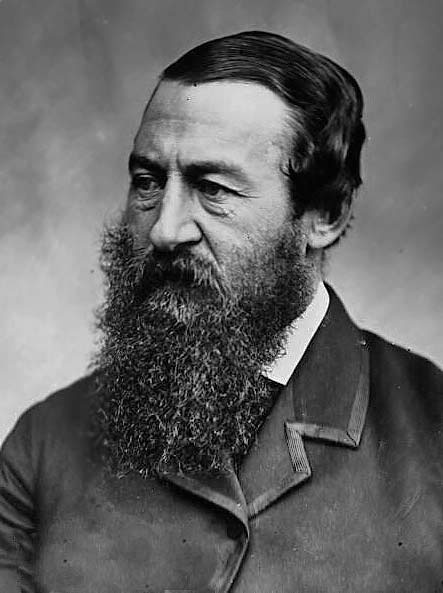

Sir Samuel Baker

Baker hadn’t appeared, but a hallelujah chorus of hounds reverberated down the glens. Suddenly, a massive deer broke the horizon. Within moments, Baker, afoot and surprisingly close behind the dogs, also became visible. The chase descended into the tree-lined valley beneath the spectators, who watched in disbelief as Baker diverted from the stag’s course and dashed headlong toward the river. Dressed in a loose-fitting shirt and tweed breeches and armed only with a sheathed knife, he formed a stark contrast to nattily attired fellow guests and homespun-clad villagers.

Soon Baker’s intentions became apparent. As he had anticipated, the hounds brought the mighty stag to bay in mid-stream and Sam braced the icy torrent to join the fray. While fighting the current, he unsheathed his knife and watched dogs worry the deer. With exquisite timing, he made a single stroke of immense power to drive his doubled-edged knife behind the stag’s shoulder into its heart. The noble animal died on the spot.

Later, basking in congratulations from the onlookers, Baker described his accomplishment with classic understatement: “It was a pretty course which did not last long. But it was properly managed and ten times better sport than shooting a deer at bay.” The estate’s keeper, Sandy McCarra, had a different perspective. With dour Scot frankness, he told Baker: “You’ve ruint the dogs forever.”

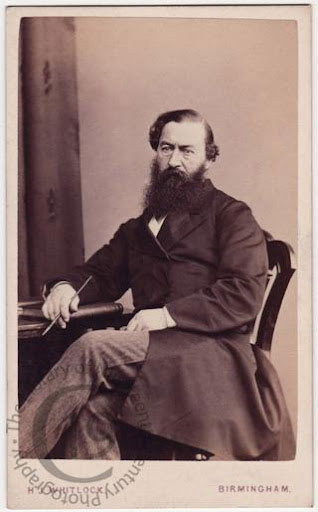

Baker photographed H.J. Whitlock of Birmingham.

Doubtless the keeper had ample reason for concern, but society’s bonds or sport’s boundaries never bound Baker. Utterly fearless, his career embraced unorthodox behavior involving sport across much the globe, grand geographical discoveries, romance that titillated Victorian society, significance in the scramble for Africa and a bon vivant’s life. First and foremost though, Baker was a hunter and among the greatest sporting scribes ever.

Samuel White Baker was born in London on June 8, 1821, the son of a wealthy ship owner with extensive estates in England, sugar plantations in Mauritius, a directorship with the Great Western Railway and chairmanship of Gloucester Bank. He was an astute businessman whose affluence formed a key influence in his son’s life thanks to his wealth opening opportunities few enjoyed.

Fair-haired and stoutly built, in youth Sam loved wandering the New Forest woods near his home. Though an indifferent scholar, he took keen interest in geography and natural history and grew into a physically powerful individual who, while still a teenager, knocked out the town bully.

When he reached age 18, Baker’s father decided his son, who had already designed a rifle for his personal use and was a prodigy when it came to weapons, ballistics and load sizes, should travel to Germany to complete his education. His special gun was a massive muzzleloader capable of carrying a belted ball of three ounces and an even heavier conical ball. The gun’s massive 16-dram charge produced so much recoil that trade opinions considered it “preposterous.” However, it suited broad-shouldered young Sam nicely, and in the future he would use similarly designed guns to telling effect.

Baker’s German sojourn accomplished little other than to provide fluency in the language. When he journeyed back to England, it was for participation in a double wedding where he and his brother John married sisters, Henrietta and Elizabeth Martin, daughters of a rector. Not too long after the 1843 double marriage, both couples sailed to the family plantation in Mauritius. Henrietta had already borne Sam a son and a second child was on the way. A third followed the ensuing year, but Baker detested monotonous plantation life and its dearth of sport. “A spirit of wandering,” strengthened by his son’s death in 1845, seized him. Before year’s end, in a pattern that typified his future, Baker left his wife and family to sail for Ceylon.

Ostensibly the journey’s purpose was to found a coffee plantation; however, his real intentions emerged when immediately upon landing he launched preparations for an extended elephant hunt. Renting “a good airy house” as his headquarters, Baker adorned its expansive verandas with “jungle-baskets, boxes, tent, gun cases and all the paraphernalia for a shooting trip.” The ensuing shikar proved successful, with Baker taking deer, elephant and buffalo. Enamored of Ceylon, he sent for his family to join him. This compulsion to pursue remote sport, never mind the practicalities, cost or hardship, would typify Baker’s entire life. He was always happiest where there was “no hum of distant voices, no rumbling of distant wheels.”

When his wife joined him, she brought sad news of their infant daughter’s death during the voyage. Heedless of his wife’s mental state, Baker sought succor in hunting. For a decade at Newera Eliya, the plantation carved out in Ceylon’s highlands, Baker hunted more than he worked, though the undertaking did become a viable economic concern.

Baker constantly experimented with new weapons, innovative hunting techniques, various loads and shot or anything likely to increase his success and, thanks to his father’s wealth, money was never a problem. As Baker perfected abilities afield and refined his techniques, he began sharing his experiences with others. In 1852 he sent Longmans the manuscript of The Rifle and Hound in Ceylon. Published the following year, it contains the hallmarks that made Baker a favorite with readers—lively prose, unfailing good humor, unpretentiousness and stirring adventure. It eventually went through numerous English editions, not to mention pirated American ones. Publication of a second book, Eight Years’ Wanderings in Ceylon, followed. It enjoyed even greater popularity.

“Every man has his own peculiar monomania,” he confided, and for him it was “a secret determination to make a trip to the unknown.”

Today, both works, while less important than Baker’s African accounts, are minor classics. Along with contributions to Field magazine, they placed him in the top ranks of the era’s sporting writers. Yet as Baker made his literary mark, tragedy stalked his personal life. He lost two sons and a daughter to Ceylon’s tropical climate. By 1854, Baker himself had suffered multiple bouts of fever, his wife was pregnant for the seventh time in 12 years, and there was pressing family business back in England. Weighted by those accumulated burdens, he reluctantly abandoned a hunter’s utopia and sailed home.

Back in England, Baker regained robust health, but after the birth of another daughter, Henrietta went into rapid decline. During a trip to the Pyrenees, taken with the intention of restoring her health, she contracted typhus and died, leaving Baker with four young daughters whom he barely knew. Whether out of guilt, sorrow or realization that he was incapable of raising his daughters, Baker dove headlong into a period of aimless wandering. He gave responsibility for his daughters to his young sister-in-law, Charlotte Martin, trusting that she and other family members would oversee the girls’ upbringing.

Seeking refuge from his inner demons, Baker hoped to fight in Crimea but arrived as war ended. Determination to become a spy checking on Russian threats to India likewise failed, so almost predictably he decided to go hunting in the Balkans. It was at that point, in the mid-1850s, he became entranced by the African explorations of Dr. David Livingstone, Richard Burton and John Speke. Henceforth dreams of Africa were constantly in his mind.

“The Black Prince” Maharajah Duleep Singh.

Modern psychologists would have found Baker a fascinating study. While reading tales of African exploration, he set out on his own European adventure accompanied by Maharajah Duleep Singh, a dispossessed Indian noble who was heir to the fabulous Koh-i-Noor diamond and son of the notorious “Messalina of the Punjab.” In self-imposed exile in England, the maharajah became interested in field sports. Years later he would kill an astounding 789 partridges (with exactly 1,000 shots) in a single day. At this juncture, however, the so-called “Black Prince” was a virile 20-year-old eager to escape Victorian society’s strictures and join a man of the world. Their float trip down the Danube River during the winter of 1858-’59 may have had dangers and certainly brought bitter cold, but according to Baker “we had three good stoves on board, lots of wood and champagne, two casks of splendid beer and wine, three English servants, fowls, turkeys, guns, etc. We were always jolly.”

Along with hunting, they visited an Austrian baron whose hobby was taxidermy, met an Indian princess being considered as Singh’s mate and roistered their way downriver. Shooting sport was indifferent, but both progressed through a series of mistresses until reaching the city of Widdin. There Baker unexpectedly found himself involved in a white slave auction when a strikingly beautiful girl caught his eye. Enthusiastic bidding followed, with Baker outbidding a Turkish sultan intent on acquiring her for his harem.

His book on this part of their African journey, The Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia, and the Sword Hunters of the Hamran Arabs, gives ample evidence of his growing fondness for Florence. It is also a volume of sport and adventure that no lover of Africa’s past should overlook.

Instead, Florence von Sass became Baker’s slave, mistress, property or his in whatever capacity he chose. Out of this unlikely union eventually came a great romance and one of the spectacular scandals of Victoria’s reign. When, long afterward, Florence stated she “owed everything to Sam,” it was the simple truth.

Faced with the stark realities of his impulsive acquisition, Baker reached a momentous decision. “Every man has his own peculiar monomania,” he confided, and for him it was “a secret determination to make a trip to the unknown.” Acknowledging “Africa has always been in my head,” he decided to “trudge into Central Africa, ever pushing for the high ranges from which the Nile is supposed to derive its sources.” Such a journey promised sport, “the chance of discovering new species,” possibility of lasting fame and time to decide his female companion’s future. Driven by these curiously mixed motivations, on April, 1861, Sam and Florence began their grand African journey.

Over the next four years, the pair would win fame while their personal linkage blossomed into a grand romance. They began by exploring the Blue Nile, where they shared hunting elephants on horseback with the Hamran Arabs. This involved some riders acting as mounted matadors while compatriots hamstrung the prey with massive two-edged swords. Baker delighted in the dangerous sport, which he pursued with adroitness and courage. His book on this part of their African journey, The Nile Tributaries of Abyssinia, and the Sword Hunters of the Hamran Arabs, gives ample evidence of his growing fondness for Florence. It is also a volume of sport and adventure that no lover of Africa’s past should overlook.

“Admirably adapted for African travel, Mrs. Baker (they weren’t actually married yet) was not a screamer, and never even whispered in the moment of danger—a touch of my sleeve was considered sufficient warning.”

Eventually the pair left the Blue Nile and journeyed toward the White Nile’s headwaters. The accomplishments of that trip included the discovery of Lake Albert, a geographical feat placing Baker squarely amongst heralded Victorian adventurers. At this point in his career, he was a splendid sight and awesome physical specimen. Decades later he gave a demonstration of his strength. A traveling strong man was entertaining at a local fair by breaking chains. Baker lightheartedly laughed at his efforts and the chagrined performer challenged him to rival his feat. Sam readily accepted. Wrapping chains around his biceps, he snapped them merely by flexing of his muscles.

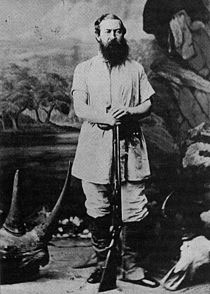

In Africa he carried a gun firing a half-pound shell. Local slavers called it Jenna el Mootfah (child of a cannon) while to Baker it was simply “Baby.” Sam’s attire was equally unorthodox–gazelle skin gaiters, cotton trousers from local fabric, giraffe hide moccasins that “laughed at thorns” and a hunting cap of woven leaves covered in gazelle skin. Everything was dyed a rich brown, in effect a type of camouflage Baker reckoned “matched well with the faded herbage and tree stumps.”

Two dangerous, demanding years ensued as Baker searched for the Nile’s source and then, after learning he was too late through meeting John Speke and James Grant following their visit to Lake Victoria, turned to an auxiliary feeder lake of which they had heard. Braving fever magnified by inadequate quinine supplies, rapacious Arab slave traders and hostile natives, Sam and Florence found strength in their growing love. Time and again Florence proved her value, and Baker later paid her due homage: “Admirably adapted for African travel, Mrs. Baker (they weren’t actually married yet) was not a screamer, and never even whispered in the moment of danger—a touch of my sleeve was considered sufficient warning.”

All was not trouble and travail on the march. Often hunting was splendid, and Baker never tired of sport or the sustenance his guns provided. Driven by Baker’s demons of discovery and strengthened by growing romance, they moved toward their elusive goal. Finally, in March 1864, they received word the lake was near. Baker left a marvelous description of the scene.

“The day broke beautifully clear, and having crossed a deep valley, we toiled up the opposite slope. I hurried to the summit. The glory of our prize burst suddenly upon me! There, like a sea of quicksilver, lay the grand expanse of water—a boundless sea horizon on the south and south-west, glittering in the noon-day sun.”

Although both were weak from fever, they hurried to the water’s edge. Baker nicely captures the moment: “It was with extreme emotion that I enjoyed this glorious scene. I rushed into the lake, and thirsty with a heart of full of gratitude, drank deeply from the sources of the Nile.”

Keenly aware of promotional opportunities, Baker named the inland sea Lake Albert, after Queen Victoria’s deceased consort. He asserted it was “the great reservoir of the Nile.” That was a considerable stretch, but the discovery assured him lasting fame as an explorer. Now he had to solve one final, devilishly difficult riddle—how to return to England and introduce Florence. After almost five years in the interior of Africa, the bone-weary travelers reached Suez. There Baker indulged in a luxury of which he had long dreamed, a tankard of iced Allsopp’s pale ale, while he sat on the veranda of the famous Shepheard’s Hotel contemplating his next move.

He had already decided he couldn’t live without Florence, so the question was how to legitimize matters. A flurry of telegrams from Egypt set matters in motion, and Baker’s brother traveled to Marseilles to meet the couple. They then proceeded to London where Sam and Florence wed in a hastily arranged private ceremony. Inevitably there was titillating gossip, an exercise in which Victorian high society excelled, but Baker maintained a bold front and simply introduced Florence as a fait accompli. Soon the exotic couple became the toast of certain segments of British society, Sam received the Royal Geographical Society’s prestigious gold medal and a knighthood followed. Suddenly, the onetime white slave was Lady Baker.

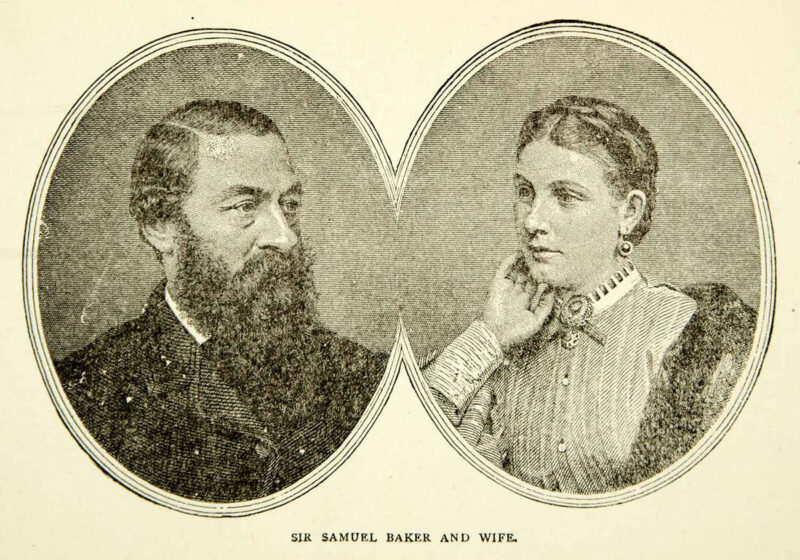

Husband and wife at last: the frontispiece from The Albert Nyanza, Great Basin of the Nile

Queen Victoria had predictable reservations on the whole matter, but Baker’s fortuitous decision to name his discovery after her beloved Prince Consort won the day. She even granted permission for Sam’s two-volume account, The Albert Nyanza, Great Basin of the Nile, to be dedicated to her. Fittingly, Florence’s portrait is positioned alongside Baker’s on the book’s frontispiece. Lively and immensely readable, the work shows Baker’s rare knack for description. Whether he was shooting an elephant, quelling an incipient caravan mutiny, or catching 300-pound Nile perch, the reader is captivated. Henceforth to an adoring public he was simply “Baker of the Nile.”

With publication of The Albert N’yanza Baker guaranteed his lasting fame as a hunter/explorer, and he could have basked in the glory of his Nile accomplishments. Instead, the next quarter century of his life saw further adventure and literary endeavor.

Financially, Baker did exceedingly well out of Nile his books, thanks to an astounding contract that gave him two-thirds of profits on all sales. That income and his substantial inheritance enabled the Bakers to live a life of leisurely affluence. Yet his wanderlust remained strong, and late in 1868 he undertook another trip to Africa, one that would lead to developments making him, by today’s standards, a millionaire many times over.

Baker had become a close friend of Edward, Prince of Wales, despite Queen Victoria pointedly informing her son that “Lady Baker was on intimate terms with her husband before they were married.” That conveniently ignored what Victoria surely knew; namely, that her son was a notorious rake. He ignored his mother’s advice on consorting with the Bakers and invited Sam to guide him on an Egyptian tour prior to the Suez Canal’s opening.

Baker as pasha, or regional governor of a district.

While in Egypt, the country’s khedive invited Baker to become governor general over vast stretches of the upper Nile. As the khedive’s agent for pacification of central Africa, Baker’s responsibilities included subjugation of the slave trade and command of a large force of men who were to bring the Sudan under Egyptian control. As Baker Pasha, he was to receive a princely salary. Money mattered, but the real inducements were the position’s luster and further opportunity for big game hunting. Thus by 1870 he and Florence were once again in Africa. The ensuing three years proved trying, and Baker failed in most of his goals. Still, he was a much wealthier man for his efforts and upon return home wrote the now predictable account of his adventures, Ismailia: A Narrative of the Expedition to Central Africa for the Suppression of the Slave Trade.

For the remainder of his days, Baker led the life of a country squire to the hilt. He wrote a fictional work for boys, Cast up by the Sea, autobiographical True Tales for My Grandsons and a major contribution to the literature of sport and natural history, Wild Beasts and Their Ways.

For the remainder of his days, Baker led the life of a country squire to the hilt. He wrote a fictional work for boys, Cast up by the Sea, autobiographical True Tales for My Grandsons and a major contribution to the literature of sport and natural history, Wild Beasts and Their Ways. Life at Orleigh Court, the Baker home, saw a steady round of visitors, dinner parties and sport. Annually there were invitations aplenty to stalk stags and shoot driven grouse in Scotland. Among the frequent visitors was Edward, Prince of Wales, and anecdotes connected with royalty at Orleigh Court abound. On one occasion Baker gave future King George V, Edward’s eldest son, a sound thrashing after he broke a limb from a prized fruit tree.

Unquestionably, hunting continued to be a grand passion for Baker. He visited India seven times and killed a total of 22 tigers. There was a bear hunting in the Rockies, sport in virtually every European country, and he even considered leading an expedition to Khartoum to rescue “Chinese” Gordon from the clutches of the Madhi and his fanatical followers. Florence put a stop to that nonsense, reminding Sam of his promise of no more grand African undertakings.

Baker, whose health had been precarious for some time, died on the penultimate day of 1893 even as he planned a Somaliland lion hunt. Hs last words were “Flooey, how can I leave you?” Typically, following Sam’s death, she ordered a 50-gallon cask of fine claret and instructed the butler to put it to good use in entertaining his friends, neighbors and estate staff. Sam would have heartedly approved. Florence lived another 23 years as the grand dame of Sanford Orleigh.

Baker enjoyed a full, fascinating life. He helped shape Britain’s destiny in Africa and stands in the vanguard of hunters who sampled and described the continent’s incomparable sport. His books have lost none of their sprightliness or readability with the passage of time. Today an extended session of armchair adventure with Baker of the Nile is an exercise in pure pleasure. An obituary notice in the Pall Mall Gazette captured the essence of this man of action with Renaissance-like qualities: “When he was not exploring he was hunting or fighting or writing.”

The most intimate and elaborately enhanced addition to the Hemingway Library series: Hemingway’s memoir of his safari across the Serengeti—presented with archival material from the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library and with the never-before-published safari journal of Hemingway’s second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. Buy Now

The most intimate and elaborately enhanced addition to the Hemingway Library series: Hemingway’s memoir of his safari across the Serengeti—presented with archival material from the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library and with the never-before-published safari journal of Hemingway’s second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer. Buy Now