He didn’t look 80 years or more; he had the timeless quality of vigorous old age, the look of extended youth often seen on the faces of old men who have preserved some boy thoughts, particularly boy thoughts upon nature…

Mill and I had finished our sandwiches and sat smoking our pipes in the calm of the high noon. An angler was coming into sight around the far bend downstream. At two hundred yards itis not easy to distinguish features and form, yet we were able to see at once that this noonday adventurer was neither kid nor novice. He was full of years and full of experience. Thigh-deep, he poled himself along in mid current with a five-foot staff, braced himself against it, and cast across and upstream. Here was a thorough-going angler with a simple and effective system. He would fish every yard of water 50 or 60 feet above him, retrieve, plug ahead with the staff to within ten feet of the previous casts’ limits, and repeat the routine of throwing flies. There was a slow inevitability about him; he drew nearer to us as the hand of a watch draws nearer the hour.

Mill and I had finished our sandwiches and sat smoking our pipes in the calm of the high noon. An angler was coming into sight around the far bend downstream. At two hundred yards itis not easy to distinguish features and form, yet we were able to see at once that this noonday adventurer was neither kid nor novice. He was full of years and full of experience. Thigh-deep, he poled himself along in mid current with a five-foot staff, braced himself against it, and cast across and upstream. Here was a thorough-going angler with a simple and effective system. He would fish every yard of water 50 or 60 feet above him, retrieve, plug ahead with the staff to within ten feet of the previous casts’ limits, and repeat the routine of throwing flies. There was a slow inevitability about him; he drew nearer to us as the hand of a watch draws nearer the hour.

For some minutes we regarded him intently, without speaking; and as he wore along, upstream, it became increasingly manifest that we were watching a supreme stylist. A grace as ancient and inbred as that of the oak under which we sat was implicit in that casting. The rhythm never varied; the man and the rod were as one, as if the rod were a physical extension of the man. The back cast was exquisitely timed; the interval of pause might have been clocked a hundred times without the variation of a hundredth of a second; the throw drew easily forward, shooting the fly far and true to the full length of the line where it hovered motionless an instant, and then settled to the water like a feather upon a casual breeze or like one of the winged seeds that sometimes drift down upon the stream. There was not the semblance of a jerk, not the minutest interruption of this oiled routine ….

Our eyes were fixed upon the all-unconscious exhibition — for he was completely unaware of an audience and something akin to a hypnotic spell fastened on us there in that heat and stillness of the noon. It was scarcely believable, such casting, and yet we were looking at it. I began to realize, as he came closer, that here was the product of many influences: of inborn genius, of years and years of application, and of something yet more — the high devotion of the artist to his art. I could see his face now, and it had upon it the pure, quiet light of elation. It was not quite smiling, but it was supremely and deeply happy with the rare happiness of mastery. I watched his face, relieved thus to divert my close attention from the intolerable perfection of his casting, and saw it to be deep-scored with life and stained with the pigments of almost a century’s weathers. The expression did not change: it was as constant as the backward and forward rhythm of his arm and body. Indeed, it was more constant, for it was still in its eternal mold after something had broken at last the iteration of that physical routine ….

For now, for the first time since he had rounded that lower bend, one of his forward casts did not come back. In this protracted spell of admiration and wonder I had forgotten that the old man was actually fishing for trout. He had not forgotten it, however, nor forgotten what to do in the event of the present contingency. For he had struck and hooked what appeared to be a heavy, deep-fighting native while I had been intent upon his face. That super-alertness, without which no trout can be hooked on a dry fly, had been there all the time, ready and waiting. The impeccable mechanics of his casting had not disturbed this nice adjustment, this essentially human equilibrium of nerves.

But now in the higher tension, in the electric air of the battle, it seemed that the machine was again dominant after its deference to the purely human interim. Here was merely another functioning of the machine: playing a trout differed from casting a fly only as the action of a motor in high gear differed from its action in low. Both were faultless, synchronized, delicately right.

I remember how that trout went away, sounding for the rocky caverns of the west bank. The water was deep in there, black under its surface of slow suds, abroad eddy backing from the main current. Salvelinus had allies, no doubt, in this submarine grotto: roots and rocks and the sunken litter that piles in every deep, still pocket of a stream. Freedom was there if he could reach it with a yard or two of not overly taut line. But the old man knew it as well, and he was keeping Salvelinus off. Coaxing him away, as it were. What impressed me throughout the struggle was the gentleness of it and the absence of haste. Watching it, I had at no time the feeling that tackle was being strained. The old man steered that boring fish away from the haven he sought in the deep eddy, back into the central shallows, and across to a clear run of water over the sandy bottom of the east side.

The fish turned downstream now, racing fast with the current and gaining slack. I held my breath. But there was a marvelously efficient stripping-in of line — a left-handed operation so casual and unhurried as to be almost contemptuous, and yet so effective that the trout came abreast of the old man on a line that held only inches of slack and went past, downstream, against pressure again.

My heart may have missed a beat or two at this juncture of the battle as I thought, for the first time, of that five-foot staff. I had come to accept that thing subconsciously — it had been so easily handled, so definitely unobtrusive in all the exercise of casting and of playing the fish — but now I realized that some sort of shift must be made as the old gentleman turned to face the battle downstream. The stick had been wedged into his right armpit, sloping away a little behind him and braced against a convenient rock to hold his slight figure in the current …. This, I felt, would be a maneuver delicate in the extreme and not without an element of real danger.

But while I deliberated about offering assistance the thing was done. It was disappointingly easy – in fact, it was no maneuver at all, but a mere pivoting of his body in a semicircle, using the staff as a sort of axis for the turn without moving its lower end in the slightest, so that now he had his prop before him instead of behind. It looked easier that way, and the thought occurred to me that, far from being concerned at the necessity of turning, he was actually relieved by it and glad of the opportunity! The whole affair was of a piece with all the rest of his stream technique – so bewildering in its facility that I began to think he must have some elemental affinity with the water itself.

The fight wore along, drew itself out to an exorbitant length, verged almost upon boredom. That trout had every fair chance to escape that any fighting trout can have and yet it had no chance. It was simply unlucky in having taken the fly of a master. That gentle, inexorable pressure wore it down, turned it again and again on the apparent edge of escape. There was a growing feebleness in its rushes, and I knew now that only one result was possible. I almost turned away — but there was still the matter of landing, the matter of handling rod, net and staff with two arms …. The old chap would drown him, perhaps, in the swift water, when the fish was completely exhausted, and thus obviate the necessity of the net.

But no; he was bringing the trout in now, but not up through the central channel. Salvelinus had worked over to the eastern shore and from there the old gentleman brought him home, yard by yard, a cross-current job through quiet water. No thought of drowning there. With 10 feet of line still off the end of his rod, the old-timer picked up his staff in his left hand, waded slowly to the shallow east shore, tossed the staff upon the bank, took the net with his now free left hand, drew the unresisting fish over it and lifted him clear.

Seventeen or 18 inches, I guessed. I could see the orange underbody gleam in the sun. A beautiful fish, a prize in any trout water in the world.

I looked at Mill and he looked at me, and although we didn’t speak I knew him to be thinking as I was, that the thing had been too perfect, too utterly lacking in any element of uncertainty. But a surprise was in store for us. The old man put the rod under his arm, stooped, and we teach hand in the stream, one at a time, shifting the net from one hand to the other. Then, with the net held under the other arm he grasped the trout in its meshes, released the fly from its mouth, and returned it very tenderly to the water. A slow ripple spread away toward midstream and disappeared. His extreme gentleness throughout the struggle was clear to us all at once.

He looked up then, saw us, and smiled. “I have kept enough of them,” he said, “in 69 years.”

“That would make him close to 80,” Mill remarked some time afterward, “if he started when he was about 10.”

He paused to change his fly and entered the stream again with the indispensable staff. The casting recommenced, caught up the accustomed rhythm — the machine was again in low gear, the hand of the watch drew away from the hour. He went ahead upstream, inching his way, his slight, brown-clad figure breasting the current, diminishing slowly in the heat shimmer of that noontime until it was gone at last around the far bend. There seemed something symbolic in that inexorable creeping progression, as if he embodied those ultimate forces which nothing can stay, like the force of truth or the cosmic forces which keep the world on the move. That steady, slow headway would stop when the stream stopped, not before; it would cease when the banks closed in upon him in the far upper rills, when there was at last no water ahead for him to aim his fly at. Unless ….

He didn’t look 80 years or more; he had the timeless quality of vigorous old age, the look of extended youth often seen on the faces of old men who have preserved some boy thoughts, particularly boy thoughts upon nature, the purest of all thoughts of boys or men. One could understand something of his fishing philosophy. Each bend of the stream, opening a new vista, was an extension of life for him. Up to the point which marked the next turn, here was a new experience waiting, a problem for the mind and body. He was in a sense deathless proof, even, against decline — so long as he could hold that interest in the next 10 minutes, so long as there was another bend to go around.

He didn’t look 80 years or more; he had the timeless quality of vigorous old age, the look of extended youth often seen on the faces of old men who have preserved some boy thoughts, particularly boy thoughts upon nature, the purest of all thoughts of boys or men. One could understand something of his fishing philosophy. Each bend of the stream, opening a new vista, was an extension of life for him. Up to the point which marked the next turn, here was a new experience waiting, a problem for the mind and body. He was in a sense deathless proof, even, against decline — so long as he could hold that interest in the next 10 minutes, so long as there was another bend to go around.

But some day, and it was not far off, there would be the last bend, the last problem of water, rocks, wind and sun. And his own errorless mechanics would meet him then face to face, the perfect functioning of physical law.

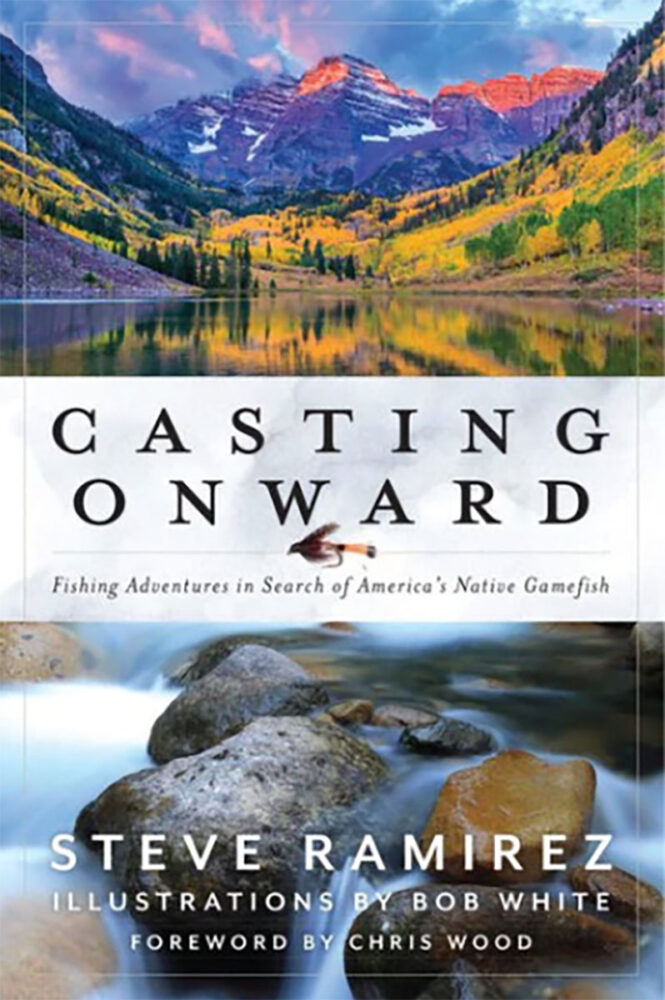

In writing this book, author, naturalist, and educator Steve Ramirez traveled thousands of miles by plane, motor vehicle, boat, and foot. Each chapter includes his fishing with a notable person in the worlds of fishing and conservation. His fishing partners in this book include Bob White, Chris Wood, Kirk Deeter (and many other leaders within Trout Unlimited), Ted Williams of The Native Fish Coalition, Matthew Miller, and John Karges of The Nature Conservancy, and many more. Buy Now

In writing this book, author, naturalist, and educator Steve Ramirez traveled thousands of miles by plane, motor vehicle, boat, and foot. Each chapter includes his fishing with a notable person in the worlds of fishing and conservation. His fishing partners in this book include Bob White, Chris Wood, Kirk Deeter (and many other leaders within Trout Unlimited), Ted Williams of The Native Fish Coalition, Matthew Miller, and John Karges of The Nature Conservancy, and many more. Buy Now