“Three Toes,” said an old rancher, with a kind of reverence, “is the fastest, longest-winded wolf that ever lived.”

A smile swept across the craggy, weather-beaten face of Clyde F. Briggs as he read a telegram from the U. S, Biological Survey: “Advise when you can leave for Rapid City, South Dakota to capture Old Three Toes.”

That was in 1925, and Briggs was operating a garage in Missouri after being relieved of his duties with the federal government. Failing eyesight forced early retirement for this veteran outdoorsman with thinning hair, solid lean frame and cold steel eyes that now squinted through heavy glasses. Homely to look at, Briggs was a respected hunter by associates who had watched his decades of success.

For 20 years he had served the federal government as a professional wolf hunter. He had chased and killed these wild creatures that mutilated the livestock of ranchers and farmers throughout the Ozark regions of Missouri and into Texas and Oklahoma. He had shot wolves, trapped them and poisoned them. He was the best wolf killer in the business and he knew it.

But then, at 60, his vision began to fail. No longer could he pickoff a wolf or coyote with a rifle as the animal ran full speed 75 yards away. The government gave him a small pension and sent him packing.

Clyde Briggs had been born in South Dakota, and his professional hunting career was spent there, but with retirement he felt a need to escape from the cold of his native state. He headed for the upper reaches of the South and arrived one day in the town of Joplin, in southwest Missouri. A week later he bought a small garage and service station.

He fingered the telegram that had come from the U. S. Biological Survey, now the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the smile that flickered across his face was one of quiet satisfaction. It was nice to be needed after all.

Old Three Toes was no stranger to Briggs, nor, for that matter, to most folks in that part of the country. The papers had been full of exploits of the formidable wolf that had been making life miserable for the stockmen of South Dakota.

Old Three Toes was no stranger to Briggs, nor, for that matter, to most folks in that part of the country. The papers had been full of exploits of the formidable wolf that had been making life miserable for the stockmen of South Dakota.

Years before, when he was a pup, he had been prowling a cattle ranch near Rapid City with two other wolves. Suddenly, they blundered into a steel trap. The other two were hopelessly caught. The pup managed to escape by leaving a toe in the trap. Thereafter, the print of the maimed foot, wherever it appeared, was like a human fingerprint, and the wolf became known far and wide as Old Three Toes. He killed not just for food, as did other predators, but seemingly for the sheer thrill of killing. Or perhaps, as some suggested, he sought revenge for what men had done to him, and could never be satisfied but must go on killing and killing.

Whatever the case, the record of Old Three Toes was a terrible one. Often, he killed from a half-dozen to a dozen animals in a single night or injured them so severely that they had to be destroyed. In one night, he could forage across no less than three ranches. His powerful jaws crushed the heads and chests of sheep. He attacked horses and cattle with equal audacity and deadliness, a lithe, lean 75-pound predator for whom domesticated animals weighing 2,000 pounds and more were simply no match.

Once, he killed six lambs in a night’s sweep and ate nothing but the liver of one of them. Then he dragged the carcasses to a common pile and crisscrossed them over each other like the corner of a rail fence. Small wonder that the rural folk of the region began to attribute human-like motives to him.

He attacked herds of cattle and sometimes ate the tails off literally dozens of them. Or he would bite a cow’s Achilles tendon in two, crippling the animal and making it easy prey when he chose to return a night or two later. It seemed to be his way of storing the meat alive until he was ready to come back and eat at his leisure.

When he struck, there was never any doubt in a rancher’s mind that his nemesis that night was Old Three Toes. The wolf’s unique footprint could be plainly seen the next morning at the killing place, and sometimes he became so audacious that he left his mark near the doorsteps and porches of ranch houses.

He was the last of the great wolves and by far the most destructive animal in the history of the country. He even achieved the distinction of being the only animal to have a bounty placed on his head by the U.S. Congress. In 1924 it offered a reward of $25,000 to anyone who brought in Old Three Toes dead or alive, the only such bounty ever authorized by Congress.

The congressmen were responding, with predictable political logic, to an outcry of ever-growing intensity in the region affected by the depredations of Old Three Toes. Rancher and farmers were yelling for his scalp. The commissioners of Harding County, where the wolf did most of his killing, posted a $500 reward.

The Biological Survey sent professional hunters to Harding County to get Old Three Toes. They hunted him every day for almost a year and even got in dozens of shots at him. Not a one touched him.

The lure of the bounties being offered for his scalp brought private hunters from all over the nation and as far away as Scotland and England. They came with their packs of trained hounds, and Old Three Toes, hearing the dogs’ baleful baying as they began to close in, took his stand on the narrow ledges of high cliffs in the Dakota badlands of the Black Hills. There, he would suck a pursuing hound into close quarters and then, with a lightning swat of a forepaw, send the hapless dog tumbling to his death on the rocks below.

“Three Toes,” said an old rancher, with a kind of reverence, “is the fastest, longest-winded wolf that ever lived.”

He told of how a quartet of brothers, furious over the extensive stock losses to Old Three Toes, chased the wily wolf 150 miles in a single week. He was easy to follow because a light snow had just fallen. Each time they stopped to rest, so did Old Three Toes. One morning, after a night’s stay at a ranch, they found, less than a half-mile away, the warm remains of a jackrabbit that the wolf had eaten. Then he had laid down in the snow, apparently waiting for his pursuers to come after him again. They spent the second night at another ranch and the next morning found signs indicating that the wolf had put down for the night less than 500 yards from the ranch house. Three Toes knew how to drive hunters to total frustration.

This was the situation that day at Joplin in 1925 when Clyde Briggs got his telegram from the U. S. Biological Survey. He packed a bag, climbed into his old Ford and drove to Rapid City. Once arrived, he parked in front of the town’s leading barbershop. You can learn a lot in a small town barbershop about what’s going on, if you have time to sort out the idle chitchat from the nuggets of information. Briggs learned the names of ranchers who had lost livestock to Old Three Toes and got back in his Ford.

He questioned the ranchers closely. He found out that, only a night or two earlier, Old Three Toes had returned to the very ranch where he’d lost his toe in the trap and killed two sheep belonging to the rancher who’d set the trap. Briggs did some fast calculating and concluded that the wolf had attacked almost precisely at the time that he, Clyde Briggs, was driving into Harding County. It was as if the creature was taunting him, daring him.

Then Briggs hiked off cross-country, following the wolf’s unmistakable trail, pausing every now and again to study its tracks and signs. Reconnoitering done, he returned to Rapid City.

It rained that night. The trail of Old Three Toes was clearly etched into the spongy earth. The man from Missouri loaded his car with traps and drove to the ranch where the wolf had just killed the two sheep. Then he set out, on foot and alone, to lay his traps.

Over a distance of more than 30 miles he put down 15 trap sets, each comprising three to five traps. They were laid along the paths that Three Toes followed in his goings and comings between the badlands and the ranches where he carried out his raids.

Briggs confidently told the ranchers and townsfolk that he would have Old Three Toes in two or three days. They were skeptical.

“Best hunters and trappers in the country — heck, in the whole world — tried to get Old Three Toes,” said one. “Now they’ve gone home, and he’s still out there.”

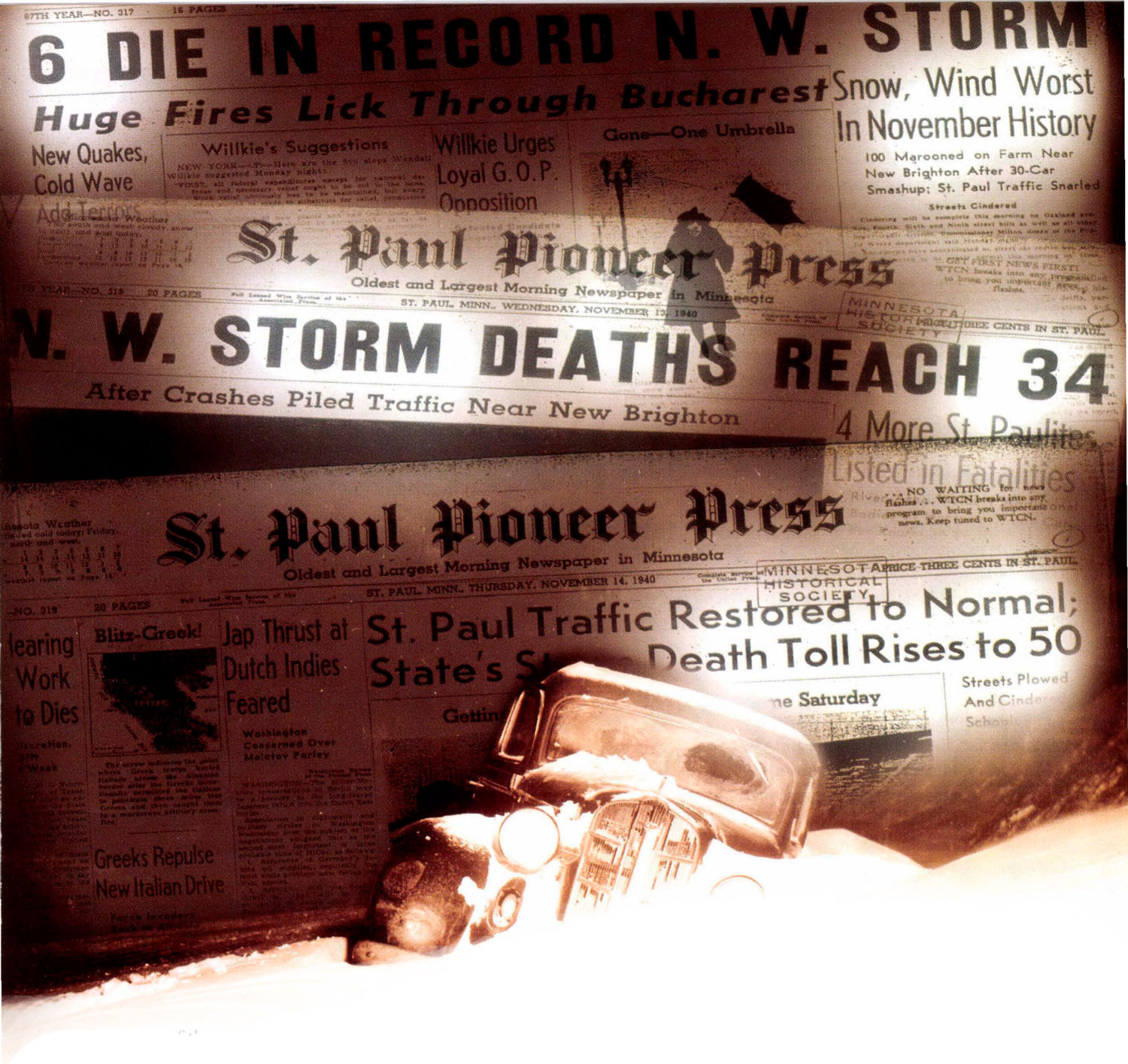

Museum exhibit recreation of Old Three Toes.

Briggs was tight-lipped with determination and certainty.

“This wolf is a gray wolf and just like all other gray wolves,” he said. “He’s meaner. He may be smarter. But he can be had.”

Two days passed. Then three. Snickers could be heard among the townspeople and ranchers. The vaunted Missouri wolf hunter was not better than the rest.

Briggs went back over the deadly trail of traps he had laid. He fiddled with them, adjusted them, moved some of them, often taking more than two hours to conceal a single three-trap setting. Even the most observant, wilderness-wise native could have stared at the scene for minutes on end and not detected the meticulously camouflaged snare.

Ten more days passed. Briggs caught coyotes. He caught badgers. He caught jackrabbits, skunks, sage hens, even ranchers’ dogs. But he didn’t catch Old Three Toes.

One particular trap set was Briggs’ favorite. He thought it had the best chance of catching the wolf. It was along a pathway that Three Toes seemed to use more often than any other.

On the fourth night after Briggs had laid that trap set, it caught a coyote. But Briggs had been right. This was a favorite approach of the artful wolf. Moments after the coyote blundered into the trap, Three Toes came on the scene. Briggs arrived just minutes later himself and saw the fresh tracks which hadn’t been there before the coyote was caught. Old Three Toes had circled the site with great wariness, doubtless watching the coyote struggle.

So now the set would have to be moved. The wolf would never step into a trap in which he had seen a coyote caught. Briggs moved it a short distance to a low rise near an old sawmill road overlooking the Little Missouri River. He liked the location, except for one thing. There was no sage bush nearby on which to sprinkle wolf bait scent. So Briggs dug up a sage bush 100 yards away, transplanted it at the trap site and sprayed it with wolf urine.

And then he waited. He waited that night and the next day and that night and the day after that. And continued to make his rounds, checking his trap sets along the entire route, re-checking, re-baiting, resetting.

On the morning of July 23, after a night of light rain, Briggs had covered about half of his 30-mile trapline and was approaching the set with the transplanted sage bush. He squinted anxiously as he edged toward the trap. Was the light playing tricks on his fading vision? Was there some kind of gray form caught therein the trap?

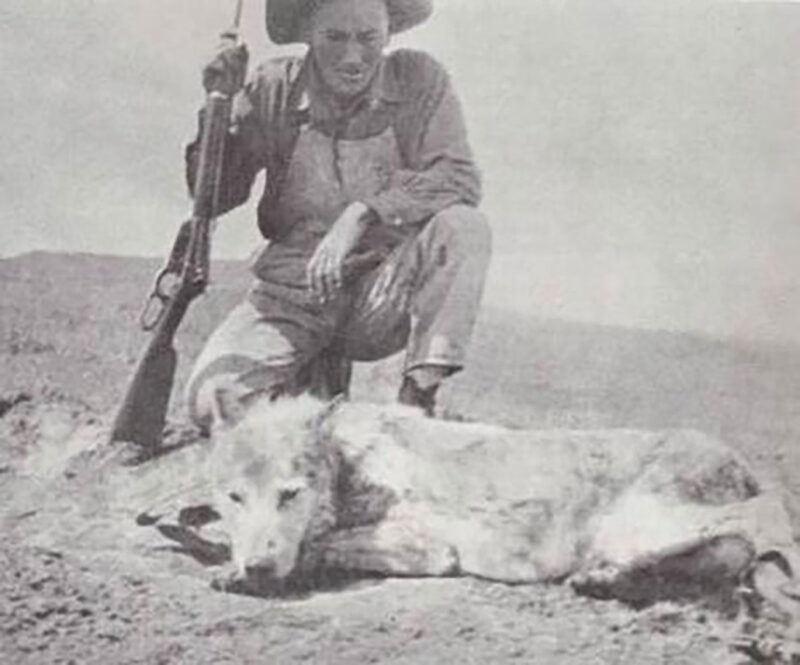

There was indeed! The great gray wolf, Old Three Toes in the flesh, lay stretched out, his head on his paws like an old dog before an open fire. As Briggs approached, the wolf raised his head, but noiselessly, without hostility, without rancor. It was as if he knew this was the end of the trail and there was no point in further resistance.

The rain-softened earth told the story. Three Toes had approached from the west, stopped to sniff the wolf-baited sage bush and thrust a forefoot into one of the traps. This time it wasn’t just a toe that got caught. The trap clamped down high on his leg. As he struggled to free himself, he stepped into another trap with a hind foot.

By the time Clyde Briggs arrived, all the fight had gone out of him. Briggs went to a nearby ranch to announce his triumph. Several men — ranchers and ranch hands —returned with him and watched while Briggs slipped a muzzle over the wolf’s mouth. Three Toes didn’t resist. Briggs lifted him into the back of the car, leaving the traps on the animal’s legs so he wouldn’t bleed to death.

“He won’t live until we get to town,” Briggs muttered as he and one of the ranchers climbed into the car and set off toward Rapid City.

A few miles down the rutted dirt road, Three Toes turned his head toward Clyde Briggs, fixed his captor with a melancholy stare and died.

How had Briggs done it? How did a half blind, retired wolf hunter from down near the Mason-Dixon Line succeed where so many had failed?

The transplanted, wolf-baited sage bush was part of the story, but only part. On the second day of reconnoitering the haunts of Old Three Toes, Briggs made a discovery. The wolf always walked in the same tracks that men made when setting the traps. He apparently sensed, with uncanny instinct and extraordinary animal intelligence, that no trapper would step on his own trap. So, when the tracks stopped, so did Three Toes.

Briggs, realizing this, left footprints all through and around the trap setting and covered them with wolf manure as additional lure. Then he backed away, stepping painstakingly backwards in his own tracks. Three Toes followed the trail up to the trap setting, and then right on into it, and voila!

They put the wolf’s remains on display in the window of a Rapid City bank. Then, an hour later, as if in silent acknowledgment that so intrepid an animal — whatever his depredations —deserved more than that, townspeople removed the wolf’s body from the bank window. They carried it to the outskirts of town and gave it a decent burial in a marked grave.

But that wasn’t the end of it. The U. S. Biological Survey came and dug up the body of Old Three Toes and sent the skull to the Survey’s district office in Mitchell, S. D. And there you can see it today.

Clyde F. Briggs kneeling over Old Three Toes.

And Clyde Briggs? Well, he cranked up his old Ford and headed back to Joplin. Catching Old Three Toes should have put him in clover for the rest of his life. But the federal government refused to pay him the $25,000 bounty on the grounds of ineligibility: He was already on the federal payroll as a hired wolf trapper at $32 a week. And Harding County withdrew its $500 reward when it heard that the feds were sending a professional hunter in to get Old Three Toes.

Briggs drew his $96 check — three weeks at $32-plus a few dollars in expense money. The local cattlemen’s association gave him a $40 watch.

Before the year was out, Clyde Briggs went totally blind. He couldn’t even tell the time of day on his wrist.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Truly a first in the world of outdoor publishing, Monsters, Mayhem and Miracles is a one-of-a-kind collection of unforgettable tales from the sporting world. Its 44 stories range from harrowing encounters with deadly predators to astonishing tales involving spirits, ghosts and even the devil himself.

Featuring both fictional and true-to-life adventures, these astonishing stories are from the creative minds of such legendary authors as Peter Capstick, Archibald Rutledge, Gene Hill, Mike Gaddis, Roger Pinckney and John Madson.

On these 354 pages, you’ll also find hilarious predicaments, stunning feats of bravery and dramatic rescues as hunters and anglers are caught up in deadly encounters with everything from bears, moose and man-eating lions to sharks and crocodiles. Altogether, you’ll not find a more endearing and absorbing collection of wild and wacky stories. Buy Now