It is a fine and joyous thing to pursue a trophy fish, but the pleasure must remain in the pursuit, not the destination. That’s the real trophy.

I want an armbuster.

A knuckle-bruiser.

A back-breaker.

A gut-wrenching, heart-pounding, adrenaline-pumping fish.

A big fish.

A fish to make the line sing.

A fish that when it breaks the surface will make me think someone has lobbed a hand-grenade at the boat.

A fish to make me think I’ve hooked the devil himself.

No more Mister Nice Guy.

I want a big fish.

Now I know big is one those relative terms. For instance, in Wisconsin, where 1 do most of my fishing, the state record brook trout is 9 pounds, 14 ounces. I count myself lucky most evenings to return from the stream with a couple of ten-inch brookies. A 12-incher is a monster to me. A 15-incher I only dream of. I’ve probably not caught nine pounds of brook trout in an entire summer.

I also know there is something, well, slightly unsavory in the desire to catch a big fish, at least in some folks’ minds. When I tell such people I want to catch a trophy, they look at me the way Great Aunt Imogene looked removing the dead mouse she found in her underwear drawer. Certainly I agree that the success of a fishing trip isn’t measured by the number or size of dead fish. There are, after all, luscious sunsets, the thrill of matching wits, the sheer freedom of being on the water.

I can buy all that. But still there’s a certain longing to land a big fish, a longing undoubtedly accentuated by the fact I tend to spend winter evenings reading outdoor magazines stuffed with color photos of fishermen playing and landing behemoths all over the world. Sometimes reading such articles makes me feel like a 12-year-old perusing his first copy of National Geographic and ogling the semi-naked natives of some vanishing primitive tribe:

Awed and overwhelmed.

It is especially easy to be overwhelmed on a February night in Wisconsin when the temperature plummets below zero, and for the fifteenth time this winter I trudge out to shovel four inches of new snow off the walk and driveway.

I could, of course, choose to pursue my dream of a big fish here in the North, where we fish what some wits refer to as “the hard water,” auguring through two feet of frozen H20 to get at the fish. And big fish can be caught: huge northerns speared through the ice or an eight-pound walleye taken on a fathead minnow.

Then, of course, there are those bass evangelists on TV fishing shows. Interesting how they always catch a ten-pound bass just when the camera’s turned on them. Or at least they claim it’s a ten-pound bass. I’ve never seen them weigh one. It’s always “Oooo-weee! That’s a big one, at least ten-pounds.” Having never seen a ten-pound bass, I’m in no position to disagree with them. Watching one such show on a snowy Saturday cements it.

My quest for the big fish demands one fish only: A bass. A big, Florida bass.

Yes, I’ve caught my share of bass, including a few I wasn’t ashamed to have recorded on Kodachrome and passed around. Some smallmouth in the two-pound range pulled from the cold lakes of Minnesota’s Boundary Waters Canoe Area, a couple of three-pound largemouth taken on frogs or purple worms in smallish northern waters. By my standards, big fish.

But not realty big fish.

No armbusters.

To catch such a big bass, one must go South, where the fish grow twice as fast and twice as large as they do in the North.

So it is I find myself one brisk March morning rocketing up St. Johns River in central Florida in the company of bass fishing guide — and 22-year-veteran of the Navy’s submarine service — Michael Westney. And rocketing is the right word. For the sedate client, Mike will hold the speed on his 1986 metallic gold Ranger bass boat to a modest 45 mph. At my request, he has unleased all 150 of Mr. Johnson’s thoroughbreds and we are pushing 60.

Actually, 45 and 60 are not that different, except its harder to keep your eyes open at 60, and when you encounter a series of swells the boat pounds over them until you begin to get a feeling for what it’s like to be body-slammed by Hulk Hogan.

We begin our quest for the big bass at Croaker’s Hole, a 40-foot deep basin in Little Lake George, a spot Mike has found productive in the past. We are fishing with shiners. At least that’s what Mike calls them. These are wild shiners between 8 and 12 inches in length, not the timid three-inch commercial variety. Hell, I’ve kept, filleted, and eaten bass the size of these shiners and been damn happy about it.

“No use messin’ with small shiners if you want a trophy bass,” Mike claims. In fact, our choice of bait and gear means it is extraordinarily unlikely we will ever hook a fish under, say, five pounds. Our shiners are hooked through the lips with 5-0 hooks that Mike has honed to the sharpness of a cat’s tooth. The hooks are attached to 20-lb. mono with an orange slip-bobber about four feet above. Although some people fish for bass with crankbaits and spinners, in March and April most big bass are taken on wild shiners.

Mike slides the boat into the bay, lifts the V-6 out of the water, and switches to the trolling motor. We’re using medium-action rods and baitcasting reels, so it takes me a while to adjust. I’m used to a flyrod or an ultra-light spinning outfit. 1 keep wanting to turn the rig upside-down. And casting such big bait is like throwing a pizza on a rope — the first couple of shiners take flight toward Miami.

Losing a few shiners is usually no big deal, but down here the big, wild kind can be scarce at times, and the going retail is $10-$ 12 a dozen in the Spring. Many of the guides run shiner traps, baiting them with dog food. Mike says he’s heard of the price going as high as $20 a dozen in some places. Now you could get a fresh Alaskan salmon dinner with all the fixings for $20. Mike, however, gets his shiners for the more reasonable price of $6 a dozen at a place called the Rodman Bait Shop on County Highway 315 west of Palatka and run by Sonny Philips. During the spring, it’s best to call ahead and reserve shiners, and you should plan on going through about four dozen a day. If you’re after a trophy bass, a lethargic or dead shiner is of no use.

Mike explains the intricacies of shiner fishing for big bass. Basically, we troll very slowly or float-fish likely- looking places. The idea is to watch the bobber closely. The shiners are as frisky as pups at first, but eventually settle down. When they start getting frantic again, “nervous as big dogs,” as Mike says, it’s likely a predator and hopefully a bass. When the bobber goes down, patience is the watchword. At the mystical right moment, you take up the slack, tighten the line, point the rod tip in the direction of the fish, and hit it.

“Hitting it” is another of those relative terms. With the fish 1 am accustomed to catching … well, put it this way, one always fears the possibility of ripping their lips off when setting the hook. In a big bass, though, you’re talking about forcing a needle through bone, so hard is the cartilage in its jaws. The guides’ universal advice is to set the hook hard enough to “cross their eyes and crack their jaws.”

It’s unneeded advice for most of the first day. I almost land an osprey that picked up my shiner, and later almost haul in a crane that does likewise. The St. Johns river is truly a birdwatcher’s paradise. Otherwise we have no action through nearly eight hours on the water. Then it happens.

While I am fiddling with one rod, Mike notices the other bobber is down. Besides having someone who can show you the best fishing spots, one good thing about a quality guide is that he’s always noticing small things that you don’t: The swirl behind the shiner, how the bobber drags when you’ve picked up some weeds, when your shiner’s too tuckered to be of much allure. For the novice, the guide will also check the tautness of the line when a fish is on and tell you when to set the hook.

Something definitely is taking the line out, singing the way I had imagined. Mike holds the line, instructs me to take up the slack, point the rod at the fish, and slam the rod over my head with all the power I can muster. I do. Or least I think so. The rod bends, then straightens a bit. “Oh no, a classic Timex set,” Mike groans. A Timex set is not a good thing. It refers to a too-easy motion in setting the hook, akin to lifting one’s forearm to check the time.

I keep the rod high though, the line tight, and begin to reel. The fish pulls back. It is an armbuster. It makes two strong runs. Once I almost get it to the boat. It leaps from the water not more than six feet away. On the next pass, Mike has it in the net and boated.

It is a big bass by my experience, the largest I have ever caught by far, though not a trophy by St. Johns River standards. Only fish over ten pounds are considered worthy of mounting. On Mike’s De-Liar mine goes seven pounds — or close enough for government work. We put it in the live-well and head back to camp.

“Camp” is Bass Haven Lodge located in Welaka, Putnam County, right on the west bank of the St. Johns. Calling Bass Haven Lodge a camp is a lot like calling all the other bass I have caught “big” fish when compared to my first on the St. Johns. Bass Haven is run by the Family Reynolds — Fred and Patty and their son Bill, though it is owned by Cleve and Judy Trimble. More hospitable and good-natured hosts could not be found anywhere.

The lodging is knotty-pine comfortable, and the meals are excellent. Imagine a companionable supper of prime rib, followed by conversation under the stars, and then a solid night’s sleep beneath a quilt in a stout four-poster, and you’ll have a good sense of Bass Haven. The Reynolds can supply you with a guide, boats, sack lunches, and just about anything else you’ll need for a day on the river.

Our second day is a case study in frustration. Early on, we have a couple of good runs and one solid hit. I had resolved not to lose a fish to the Timex set. For the first bass, I set the hook so hard Mike thinks I have thrown myself overboard. Fortunately, since there are alligators in the vicinity, I haven’t; unfortunately, the fish comes up fighting and shakes free. Though not a trophy, it was at least six pounds.

We get into a couple of other intriguing possibilities and cover a whole lot of river, including the barge canal to Rodman Reservoir and masses of lily pads on the Ocklawaha River. For our efforts I manage to catch an alligator gar and a chain pickerel. The latter is a Southern cousin of the northern pike, a much sought-after fish in Wisconsin. The fish I caught would have been gladly kept if pulled through the ice or taken on a Daredevil back home. Here it’s a trash fish and is tossed back. Ah, relativity again.

My guide is getting more and more into my quest for a trophy bass. He has increasingly begun to switch from coaching me to coaching the fish, admonishing them: “Com’n little darlin’, bite! Hey, big Bertha, take that shiner and void its warranty!” and “Com’n girls, let’s rock and roll!”

I discover something today, namely that no matter where you’re from, the excuses for not catching fish are the same. Yesterday we encountered some folks who lamented that fishing was poor because the wind was from the northwest; today we met other anglers who declared that fishing was off because the wind was from the southeast. I’ve used the same excuses myself.

After nine hours on the water in 70-degree temperatures, I call home. My wife says it is snowing and another five inches are predicted. With great effort she sympathizes with me about my sunburned nose.

Going to bed I find a quarter-size bruise on my abdomen from the impact of the rod-butt when I set the hook that morning. Tomorrow Mike will pick me up at 5:30 to spend the day at Rodman Reservoir.

The third day we fish our hearts out.

Mike picks me up promptly at 5:30. After a breakfast of sausage gravy over biscuits, we head out to spend the entire day on Rodman, a huge backwater formed with the idea of creating a pan-Florida barge canal. Rodman is a source of considerable controversy. Bass fishermen love it for it harbors some monster bass. Mike tells of taking a 9-pounder and 14-pounder on the same day. The pan Florida canal was never completed, and now Rodman is choked with weeds, notably hyacinth and hydrilla. In 1985 millions of fish died off in Rodman; now environmental groups would dearly like to see the dam blown and the Ocklawaha River channel restored. It seems to make sense.

Despite the controversy, Rodman this morning is a place of haunting beauty. Hundreds of ducks scatter as we motor carefully down the stump-strewn channels. Dead trees stand in stark silhouette against the muddy morning sky. Occasionally the sun beams between the clouds, turning the water the color of old silver.

We still fish. We troll. We fish shallow. We fish deep. We fish in between. We fish the canal, the stumps, the lily pads, the hydrilla, the eelgrass. We fish in the hot sun and in the brief, cool rain. We fish long and hard, and finally around 3:00 we give up on Rodman. We have caught no bass, nor has anyone else we’ve met.

We return to the stretch of St. Johns where I took my big fish. We troll for nearly three hours until darkness grows over us and the first stars blink on. Then we give it up altogether.

We are both disappointed that I have not taken a bass over ten pounds. But somewhere during our long hours on the water, the thought had occurred to me that something wasn’t quite right in my own psyche. Generally, I’d rather be fishing than not fishing, catching fish than not catching fish. But today it seemed that my manic preoccupation with catching was overshadowing, perhaps even destroying, the pleasure of fishing.

And it wasn’t as if I didn’t catch any fish. I took five nice chain pickerel — all over 24 inches. This would have been an outstanding day of fishing under any other circumstances. Here they’re called “jack fish” and they’re thrown back with a sigh, if not a curse. The same way we in the North treat eelpout or carp. Or even catfish.

Also, I’ve seen an extraordinary diversity of wildlife — alligators and water moccasins, ghostly manatee drifting through the shallows, huge gar splashing wildly right next to the boat. I have seen an array of exotic birdlife — cranes of all kinds, red-headed woodpeckers, vultures, pelicans, and ubiquitous osprey that swoop from the sky to grab a cast-off shiner. Early evening has found an owl perched in the moss-shrouded live-oak only ten feet from my room posing its unanswerable questions.

All of these things should more than make up for the absence of a ten-pound bass.

Driving back with Mike I ask if the pressure of having to take clients out and their high expectations ever gets to him. Has he ever had an irate client? He answers no on both accounts. Like the baseball pitcher or the quarterback, Mike asserts that when guiding stops being fun, he’ll stop doing it. His wife is a teacher and he has his military pension. He says he is not interested in working and worrying himself into an early grave.

Still I wonder. Before Mike drops me off, we stop by his house so he can let his wife know he’s off the water and safe. They have kindly invited me to dinner, but I am too tired and decline. I’m nearly asleep in the saddle when Mike returns with his seven-year-old son, Scotty, fresh with that sweet scent of children who’ve just had their hair washed. Somewhere in a conversation about how boring school is and a tale about a diamondback rattler, Scotty slips in that his Dad needs to get more sleep. Guiding is not an easy life.

The pressure of putting clients onto bass isn’t the only thing to give guides sleepless nights now and then. There’s also the behavior of some clients, especially those who insist on keeping and cleaning all the bass they catch.

Mike relates how one fishing party insisted on keeping all their fish — a couple of eight pounders and a few smaller ones. The guide, reluctantly cleaning the fish, turned to the clients and was unable to hide his feelings as he held out handfuls of yellow roe and said, “Look at that. Two billion dead bass so you can have a meal.” The clients didn’t seem to understand. Releasing the fish isn’t just good conversation; it’s also the way a guide preserves his livelihood.

And then there were the clients who not only caught a passel of bass, but also landed a 12-pounder. Were they happy? No. They thought that for the price of the guide (about $175 a day), they should have taken more fish than they had. As one of the guides put it in his colorful, good ol’ boy voice: “Those guys wouldn’t have been happy if they’d each taken a 15-pounder and you had a bimbo in the boat for them besides.” He chose a more descriptive word than bimbo. These guides are a whole different species from those bass evangelists on TV.

Mike and I part, and I think he is more disappointed than I at not taking a trophy bass. Yet I have taken a trophy, a personal world record, a lovely, fat seven-pound bass that we took pictures of and returned to the water to drop its roe. With luck, in another couple of years, that bass will be a ten- pounder. Perhaps it will wait for me or another Northerner tired of the winter and longing to catch an armbuster.

Perhaps it is also true that a trophy fish often comes when you least expect it. Consider that the world-record bass of 22 pounds, 4 ounces was caught back in 1932 by a teenager named George Perry. He was fishing from an old rowboat with a metal rod. He no more expected to catch a world record than I expect to be the next pope. Taking a trophy should always be a surprise, the result of hard work, persistence, skill, and, of course, pure luck.

Circling the airport and descending into central Wisconsin, I catch sight of cows grazing a snowy pasture. They look like so many ants in a sugar bowl. Beyond them,I glimpse the Wisconsin River, still frozen in places.

Already some walleye fishermen will be gathered below the spillways by the paper mills. One or two may go home with a trophy. Should they hook and land a northern, they will be delighted and take it home for eating or pickling. In another two months it will be opening day statewide. The truth comes to me then. It is a fine and joyous thing to pursue a trophy fish, but the pleasure must remain in the pursuit, not the destination. That’s the real trophy.

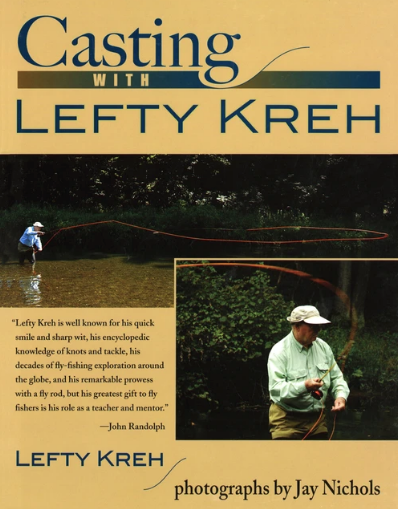

With over 40 casts covered in step-by-step detail in over 1,200 full-color photographs, Casting with Lefty Kreh is the perfect reference for the fly fisher who wants to improve his skills. Casting should be nearly effortless. Understand the physics and the dynamics of casting and how to adapt to various fishing conditions and your casting will greatly improve. That has been Lefty’s philosophy since he began teaching fly casting over fifty years ago.

With over 40 casts covered in step-by-step detail in over 1,200 full-color photographs, Casting with Lefty Kreh is the perfect reference for the fly fisher who wants to improve his skills. Casting should be nearly effortless. Understand the physics and the dynamics of casting and how to adapt to various fishing conditions and your casting will greatly improve. That has been Lefty’s philosophy since he began teaching fly casting over fifty years ago.

By fishing all over the United Sates and many parts of the world, Lefty learned the techniques experts use on different waters, in every situation imaginable. He shares that knowledge here through easy-to-understand instructions and full-color photographs the show exactly how to make every important cast. Shop Now