In New Mexico, herds of pronghorn are typically found roaming the high plains throughout the eastern part of the state. This expanse of land varies in elevation between 4,000 and 7,000 feet.

A particular herd of a few hundred, however, spends the warmer months at nearly 11,000 feet, east of Chama near the Colorado border. Here, the animals navigate dense vegetation, usually the habitat of deer and elk.

While the existence of this herd, migrating up into the mountains every spring, has been known for years, little is known about the herd’s history. It is currently not known when the herd established itself in this area and why.

Biologists Orrin Duvuvuei and Nicole Tatman collar a pronghorn during a capture survey in late September. Photo by Earl Watters.

The fact that these animals are able to survive at this high elevation is unusual for their species. No other pronghorn in the state live at such a high elevation. Other western states are also home to high altitude herds. Pronghorn can be found in alpine meadows, reaching 11,000 feet elevation in Oregon and Wyoming, according to the U.S. Forest Service.

This past September, the Department conducted the first pronghorn capture in this area in an effort to gain a better understanding of the herd’s migration pattern. The study is part of a U.S. Department of Interior initiative announced in 2018 to improve habitat conditions in big game migration corridors and winter range areas throughout the western U.S. on federal and private lands whose owners volunteer to participate in conservation efforts.

In May, Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt unveiled the award of $2.1 million in grants to state and local partners in western states for habitat conservation activities in migration corridors and winter range for elk, mule deer and pronghorn. The Department’s study of this unusual pronghorn herd—in an area consisting of U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management and private lands— is funded by one of these grants.

The study began when Department biologists captured 17 pronghorn and released them with Global Positioning System (GPS) collars to monitor and track their movements.

“Where they spend their summer months is literally on the Continental Divide,” said Orrin Duvuvuei, deer biologist and migration coordinator with the Department.

As fall moves into winter, biologists expect the herd to move east to lower elevations, taking a migration route that, albeit quite short when compared to longer wildlife migrations, should nonetheless be conserved, he explained, noting that the significance of migration routes aren’t dictated by their length.

“Just because a herd moves a long distance doesn’t mean its migration path should be the only corridor preserved,” Duvuvuei said.

Pronghorn prefer grasses shorter than two feet, better for spotting predators such as wolves—historically— and coyotes, said Anthony Opatz, pronghorn biologist with the Department of Game and Fish.

Open prairies offer safety for pronghorn. The animals are considered the fastest in North America, able to run from predators at approximately 45 miles per hour and sustain 30 to 40 miles per hour for several miles, Optaz noted.

This habitat offers plenty of forbs to eat, especially when there is more precipitation.

Up in the mountains of northern New Mexico, the herd seems to have found suitable habitat with abundant food. In fact, that habitat looks similar to their native lower elevation range, offering openings with little to no trees among an area made up of mostly dense forests, Opatz said.

Pronghorn are typically found roaming the high plains of New Mexico. Department photo by Martin Perea.

“These high elevation openings look like lower elevation prairies that are typical pronghorn habitat,” Opatz said. “It’s so wet up there most of the summer months. Rainfall there is higher than on the plains a few thousand feet below. It’s green with food.”

The characteristics of this habitat are more important than elevation, adds Duvuvuei. “That’s what makes this particular area more unique— it’s not vast expanses of plains and grasslands, it’s dense forests interspersed with pockets of meadows.”

Another reason for this herd to seek this high elevation area is that pronghorn have high fidelity to birth areas, Opatz said. “If they’re born there, they won’t move too far. They may seasonally move around but they will follow the same group they were born with. Migration is a learned behavior. These pronghorn have probably had this behavior for hundreds of years.”

Their ability to survive at a high altitude is not surprising. “Pronghorn are a super-variable species,” Opatz notes, explaining that in North America, the animals can go from the hottest deserts in Mexico all the way up to southern Manitoba in Canada.

Biologists have thought some ungulate herds don’t migrate, only to find out that is not true, noted Nicole Tatman, big game program manager with the Department, who captured and collared the pronghorn with Duvuvuei earlier this fall. In the southwestern part of the state, there are some lower elevation herds of pronghorn that may migrate; however, the Department has yet to collect data on them.

Over the next year, as the collared pronghorn near Chama are tracked via GPS, biologists expect to gain a better understanding of the herd’s migratory path.

If biologists do pinpoint a definite migration path, then measures could be taken to ensure the pronghorn’s route remains open and undisturbed.

“If the herd couldn’t move from this area, the pronghorn would starve because their food sources would be covered with snow,” Opatz said. “We want to see what migration routes they are using. Once we determine the exact routes that are being used, then we can explore if there are conservation practices we can do to help unique herds, such as this one, persists.”

The Department will track the 17 animals in this herd for several years, at least until their GPS collars stop transmitting signals, said Tatman. The team plans to capture more pronghorn on their winter range in January with the goal of collaring a total of 40 animals for this study.

She expects the data will help the team determine ways to maintain the migratory path, particularly if the animals are inhibited by roads or fences, or as development increases in the area.

“If this is an important route, we’d like to maintain it,” she said. “We may be able to work with land management agencies or private landowners on habitat improvements to make that area friendlier for pronghorn to move through.”

Biologists said the study, which contains Game Management Units (GMUs) 4, 51 and 52, will also help the Department determine whether pronghorn hunting opportunities can be expanded and where. Currently, in GMU 52, pronghorn are hunted on public and private land. In GMU 4, the hunting opportunities are all on private land. A pronghorn hunting season is not available in GMU 51.

In addition to tracking the movement of these pronghorn, in the coming months Department biologists will also collar elk and deer that make similar migrations as the seasons change.

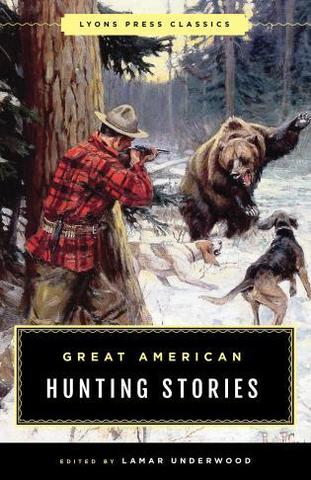

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Shop Now

A superb collection of stories that captures the very soul of hunting. For hunters, listening to the accounts of kindred spirits recalling the drama and action that go with good days afield ranks among life’s most pleasurable activities. Here, then, are some of the best hunting tales ever written, stories that sweep from charging lions in the African bush to mountain goats in the mountain crags of the Rockies; from the gallant bird dogs of the Southern pinelands to the great Western hunts of Theodore Roosevelt. Great American Hunting Stories captures the very soul of hunting. With contributions from: Theodore Roosevelt, Nash Buckingham, Archibald Rutledge, Zane Grey, Lieutenant Townsend Whelen, Harold McCracken, Irvin S. Cobb, Edwin Main Post, Horace Kephart, Francis Parkman ,William T. Hornaday, Sc.D, Rex Beach, and more. Shop Now