I must confess that my heart failed me for a moment, for it was clear that I had now to deal not with two or three wandering wolves but an entire pack.

If one is in the humor, there is nothing more delightful than to pass a night in the depths of a Russian forest. Stretched upon a couch of hay, well wrapped in fur or sheepskin, with one’s feet toward a fire of dead pine branches, one may lie gazing at the somber pines and dream all manner of marvelous fairy tales.

Many and many a night have I spent lying thus beneath the dark trees of the densest Russian forests. It is the ideal of absolute peace. Only the keeper is astir, prowling in and out of the flickering rays, busily but silently collecting fallen twigs to keep the bonfire going. When he, at length, sits down to smoke his long Finn pipe, there is nothing to break the stillness. This is rest, perfect rest, for mind and body; good for the soul, too. How very far away seem care and sin and work, and all the miseries of everyday existence.

As though to belie the thoughts, a most dismal noise suddenly mars the stillness. It is a wolf. The holy peace of night is broken; thoughts poetical may as well take flight, for that wolf, having once begun to howl, will continue to make the night hideous until he shall have found something to eat or withdrawn out of hearing.

I know his habits well, and have had some narrow shaves with him. The nearest, perhaps, was on just such a night as this, when I was living in the same village with Simeon, who was a keeper, and hunting with him.

One day in that winter—little Father, how cold it was that year!—we discovered wolves in the neighborhood; in fact, one or two of them had entered the village during the night, as wolves will when it is very cold, and killed two dogs and old Timoshka’s only horse. Timoshka had no proper shed for the horse, and it was tethered inside an old, ruined barn, which lay just beyond the last house of the village. The wolves had only to help themselves and go away, and no one was any wiser until the next morning . . . except, of course, the horse and the two little dogs, whose wisdom was not of much service to them.

Simeon and I did not take long in making up our minds that one or more of the skins of those thieving wolves should be ours before next morning. The only point to be decided was which of the several methods of getting at the brutes should be adopted on this occasion.

We decided to try the suckling-pig argument upon them, this being the plan which would give us the most speedy results. We might have killed and laid down a horse or cow, but possibly we should have been obligated to wait two or three days before the scent attracted our quarry, and old Timoshka was all the while begging us, with tears in his eyes, to lose not a moment in executing summary vengeance upon the thieves who had robbed him of his only horse.

It so happened that Simeon’s sow had a litter a few weeks old, and one of the youngsters, Simeon said, was especially suitable for our purpose, in that it was possessed of as strident a voice as ever helped to make a pandemonium of a pig sty.

This was just the pig for us, for the louder your pig squeals, the better is your chance of attracting the wolves. So Simeon and I took the little porker, taking also a good supply of something to keep out the cold, harnessed my horses to the sledge, put on our sheepskin shubas, loaded our guns with slugs, and, at about ten o’clock at night, started off into the woods.

Simeon had not exaggerated when he praised the vocal talent of his little pig. As a rule, one is obliged to pinch the little creature’s tail at intervals in order to keep its vocal energy up to the mark, but this gallant little animal required no such incentive to do its very best for us. From beginning to end it yelled as though its last hour had come. Never had I heard such a din; it was so deafening that Simeon and I were obliged to speak rather loudly to each other, which may explain why, for a long while, no wolves appeared to accept the invitation which we, in the person of our little porker, held out to them.

We glided along for at least two hours without a sign of a wolf. The forest was dense on both sides of the road, and though it was a fairly light night, we could not see very far into the depths of the dark pines. We began to be afraid, at last, that the brutes had left our part of the world.

All of a sudden, just as we reached a spot where there was a small open space at one side of the road, the horses gave a frantic shy, banging the side of the sledge against a tree and tipping it over. Simeon held on tight to the reins, but I, taken unawares and having both hands employed in holding my gun, flew clean out of the sledge and went, head foremost, into the snow.

When I had finished my gyrations, I became aware of two things: one pleasant, the other very much the reverse. I found that I had somehow managed to keep hold of my gun; that was the agreeable discovery. The unpleasant part of the matter was the distant view of Simeon’s back as he careened away at full speed, half in and half out of his sledge, which the frightened horses were dragging along as fast as they could move their galloping hooves. Simeon was pulling at the reins and swearing at the runaway steeds, but without the slightest effect. In another minute, man, horses, sledge, and squealing pig had disappeared in the dusky distance.

Then, suddenly, I became aware of the cause of the horses’ terror. Standing quite still and half-hidden in the shadow of a pine tree was a huge gray wolf. I was in the very act of raising my gun, in order to make sure of him while I could, when a movement on the right attracted my eye and stayed my arm. Turning to see what this might be, I perceived a second wolf, while a third and a fourth seemed, at the same instant, to issue out of the darkness and to stand, grim and silent, beside or close to the others. I turned my head half round and glanced over my shoulder. A fifth wolf was there. I turned again and a sixth and seventh were there.

I must confess that my heart failed me for a moment, and with good reason, for it was clear that I had now to deal not with two or three wandering wolves but an entire pack.

As everyone knows, the wolf is a very different animal when supported by his fellows, in force, as compared with the same creature when by himself, or with only two or three others.

Now, while I felt a considerable sinking at the heart when I realized the somewhat startling truth, I did not lose my head. On the contrary, I do not think that I was ever in my life more clear headed, though I felt that the chances for my escape were slim. I had, of course, reserved my fire; this would be my very last resource.

I remembered to have heard, somewhere, that on a certain occasion a belated traveler had been surrounded by a pack of wolves in a forest and had kept them at bay by the simple process of remaining awake and refusing to succumb to the frost. The wolves, he is supposed to have declared, squatted all round him, waiting for him to die or to fall asleep—which comes to the same thing—and dared not attack him before death supervened. I had never believed this story, but in spite of this fact I was pleased to remember it at this crucial moment.

My first step was to pick out a large tree, the largest in view, and to edge toward it, with the intention of placing my back against it in order to secure myself from an attack in the rear. By this time there were 11 gaunt, gray brutes, and they watched me silently, keeping in the shadow as much as possible. It was but a few paces to the tree, which I had chosen as my sanctuary, and by dint of moving an inch or two at a time I managed to reach and place my back against it. So far so good.

Then an idea struck me: Why not turn quickly and shin up the tree before the brutes could seize me? It was not a pleasant reflection that, in all probability, they would have me by the leg before I should be able to climb beyond reach.

However, I have always been, since my boyhood, about as good a climber as you will see outside of a monkey-house, so I determined to have a try.

The wolves were at this time about 20 paces distant from me. The tree had no friendly branch to which I could cling and haul myself up; it was a straight, bare trunk that I must negotiate—ugh! It was not a pleasant moment! However, the thing must be attempted, so I had better get it over. I turned suddenly, dropped my gun, and sprang with all my might and agility up the thick, mast-like stem. In an instant every wolf gave tongue and sprang toward me.

I scrambled for dear life. The whole affair occupied but a couple of seconds, yet for all that I very nearly succeeded in my attempt. I managed to shin up the tree to a height of about five feet, when I felt a violent tug at my right foot, together with a twinge of pain. One brute of a wolf had been too quick for me…

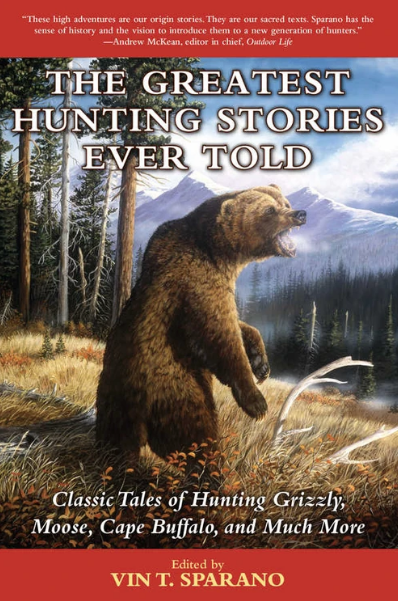

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game.

Now, for the forty million Americans who hunt, here is the perfect companion. The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a collection of true hunting tales, told by some of the most courageous and clever sportsmen. The quest for adventure has touched all these writers, who convey the drama, tension, stamina, and sheer thrill of tracking down game.

Included here are the experiences of Teddy Roosevelt in “The Wilderness Hunter,” of Jack O’Connor in “The Leopard,” of J. C. Rickhoff in “Wounded Lion in Kenya,” of Frank C. Hibben in “The Last Stand of a Wily Jaguar,” and of John “Pondoro” Taylor in “Buffalo,” among others.

Collected by a lifelong devotee of hunting literature, the stories here are classics. In more than two dozen selections, the true experiences of hunting a variety of animals are relayed by the most reliable eyewitnesses: the hunters themselves. A must for all hunters and armchair adventurers, The Greatest Hunting Stories Ever Told is a real trophy. Buy Now